Clinical Considerations

• To understand how clinical experience is related to the theory and lecture portion of dental anatomy

• To understand how preventive clinical situations are related to tooth form and supportive dental structures

• To understand how occlusal trauma and the natural shape and contour of the teeth can contribute to dental disease

• To understand how the placement of a restoration can contribute to disease of the supporting tissues

• To evaluate the reliability of dental pain as a diagnostic aid

• To understand how tooth migration can affect the success of treatment or necessitate different treatment

PREVENTIVE CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

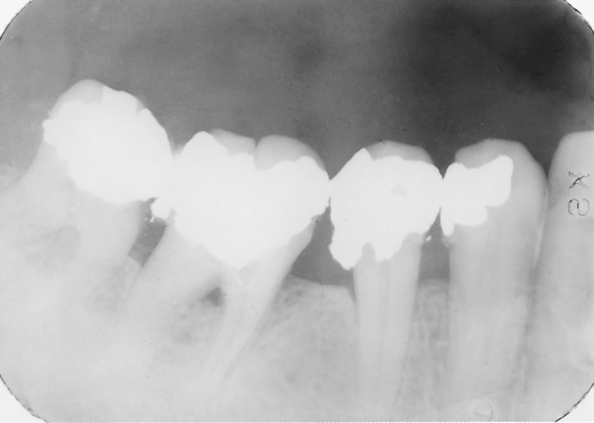

Decay and Periodontal Disease

However, not all periodontal disease is initially caused by bacteria. If the tooth has rough pits, grooves, or fissures, these areas allow debris to accumulate and provide a breeding ground for bacteria. The same is true if the tooth has rough margins on its restorations or if the tooth interproximally has an overhanging restoration—that is, a restoration that does not stay within the confines of the tooth form but protrudes into the gingival tissue. Bacteria can adhere around the margins of the excess material and lead to disease within the gum and tooth tissues. Restoration of any tooth must follow the normal anatomy of that tooth. A restoration must be polished smooth so that the tooth can resume normal function and the jaw its normal anatomy. Dental personnel provide a valuable service in preventive dentistry by polishing dental restorations. It is much more comfortable for patients to undergo the polishing of their restorations than a replacement (Fig. 9-1).

Trauma

The hardness of enamel helps prevent occlusal wear or attrition, but this same hardness allows the full impact of trauma to be transferred from tooth to bone. If a tooth prematurely contacts another, only the two teeth will bear the initial brunt of forces when the jaws are closed. A more ideal situation is to have all the teeth hit equally on closure of the jaw, without any teeth hitting prematurely. This allows for the forces exerted to be dissipated over all the teeth. Should one tooth hit with a greater force than the rest of the teeth, it will be traumatized by this excess force. Such a situation is known as occlusal trauma and results in disease of the periodontal tissue, cracking of the enamel of the tooth, and possible fracture of the tooth (Fig. 9-2).

Contours of Teeth

The contours of the teeth, buccally and lingually, determine the angle at which food is deflected off the teeth and onto the gingiva. If the buccal or lingual contours are underdeveloped (undercontoured), food and debris are pushed into the gingival crevice. If the buccal and lingual contours are overdeveloped (overcontoured), the food and debris pass off the tooth and onto the gingiva at a poor angle. This results in gingival inflammation because the gum tissue is denied proper frictional massage (see Fig. 3-6).

THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Maintaining Form in Restorations

Because it is very important in the restoration of teeth to reconstruct a tooth in its anatomic form, knowing the anatomic shape of each individual tooth is also important. Contact areas and buccal and lingual contours should also be learned. For instance, an overhanging restoration or an open interproximal contact is undesirable in restoring a tooth in the interproximal area. Measures should be taken to keep the filling material from impinging on the tissue. To prevent such overflow, a metal band is placed around the tooth and wedged into position (Fig. 9-3). This matrix band retains the ma/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses