Abdominal Trauma

Evaluation and Management

Abdominal examination is an adjunct to primary survey in hemodynamically unstable patients forming part of the assessment of circulation, specifically to confirm or exclude the abdomen as the source of concealed bleeding. In a stable patient with a history of chest or abdominal injury or symptoms, the abdominal examination is part of a secondary and tertiary survey.1 Facial or closed head injury examination is secondary in the evaluation unless significant airway instability impedes proper access and control of ventilation. Any wound from the nipple to perineum anteriorly, to the vertebral column posteriorly, and bilateral flanks are the boundaries of abdominal review and the common areas of trauma. Mechanisms of injuries may be penetrating or blunt. The most common cause of mortality in abdominal trauma is secondary to delayed resuscitation or excessive hemorrhage with inadequate volume resuscitation. Intra-abdominal organ injury and rupture or perforation precipitates gastrointestinal (GI) content spillage into the peritoneal cavity, frequently leading to peritonitis and delayed mortality from severe sepsis.

The abdomen can be deceptively benign on initial assessment, with a precipitous change in clinical status. The most significant pitfall is delayed recognition of occult abdominal injury.2

Mechanisms of Injury

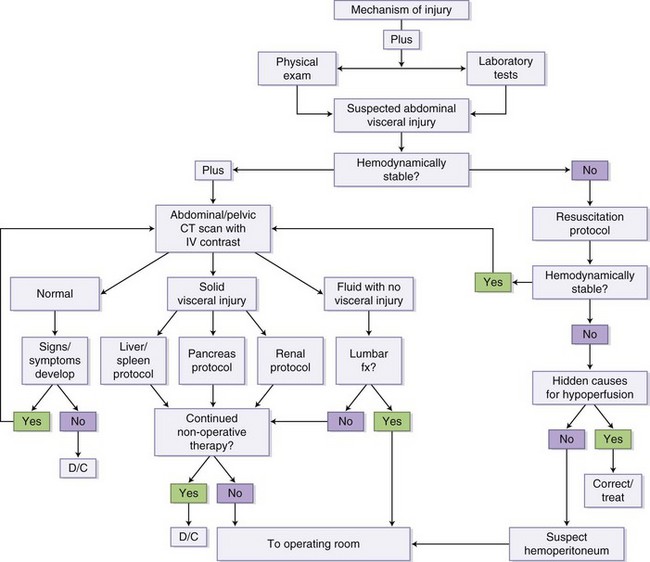

A concentrated area of force on the abdominal area has a higher risk of injury to underlying organs (Fig. 9-1). The impact can be in the form of a blunt object such as a steering wheel or car door. The vector and velocity of the trauma become important to the clinician. To understand the mechanism of injury better, the treating physician should seek to obtain information from the injury report or from the paramedics. Often, the transporting medical personnel have obtained the accounts from witness information as well as assessment from the injury scene. This information forms a vital component of the clinical history and the likelihood of underlying injury.

FIGURE 9-1 Mechanism of injury algorithm.

Examination

Abdominal examination in trauma must be a continuum of evaluative and diagnostic steps rather than a brief physical review of the patient. Any patient with chest and abdomen complaints is assumed to have intra-abdominal injury until proven otherwise.3

Trauma Scores and Indices

Trauma grading systems are comparative indices for quantification and description. These can be extrapolated for diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic measures. Commonly used indices are the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) and the Penetrating Abdominal Trauma Index (PATI).4,5 Previous editions of AIS (severity scale from 1 to 6) were for blunt trauma; the most current modification extends to include penetrating trauma. PATI has individual organ scores summative to a score of 25. Its major drawbacks are inadequate quantification for multiple complex injuries involving a specific anatomic area.

Adjuncts to Physical Examination

Most adjunctive examinations are not performed in a stable, alert, cooperative, and asymptomatic patient who has suffered low-force transfer to the abdominal wall or internal organs. Any complaints of shoulder or abdominal pain, nausea, unrestrained patients, impairment by alcohol or drugs, visible contusive signs, and open injuries mandate abdominal examination adjuncts.3

Adjunctive Diagnostic Studies

Urinary Catheters.

Urinary catheters are useful for decompression of the bladder, urinalysis for macroscopic and microscopic hematuria, and monitoring adequacy of fluid resuscitation. Scrotal hematoma, perineal ecchymosis, pelvic fractures, blood at the meatus, high-riding prostrate with unstable pelvis, hematuria (>50 red blood cells [RBCs] per high-power field [HPF]) and inability to void are relative contraindications to urethral catheterization. In these cases, retrograde urethrography (RUG) is often used to diagnose urethral injury.6

Diagnostic Workup

Imaging Studies

Plain Radiography

Anteroposterior (AP) chest and pelvic radiographs are standard initial assessments of patients with multisystem blunt trauma. If the patient is unstable, no radiographs are needed in the emergency room.1,3 A radiographic marker on entry wounds of a penetrating injury may aid in determining the trajectory and path of missiles.

Focused Assessment Sonography in Trauma: Ultrasonography

Focused assessment sonography in trauma (FAST)7 is a well-established trauma assessment by ultrasound of the cardiac, bilateral renal, and pelvic area that has been validated in several prospective randomized studies. FAST is operator-dependent but has great sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy comparable to diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) and computed tomography (CT) for assessing intra-abdominal fluid and involves no radiation exposure or contrast administration. The advantages of FAST are immediate bedside intra-abdominal visualization, its noninvasive portable nature, avoidance of transport to radiology, and ability of repeat examinations to monitor interval changes. It is performed to document fluid in the pericardial sac, hepatorenal space (Morrison’s pouch), splenorenal fossa, and pelvis (pouch of Douglas). Negative FAST results do not preclude the need for further evaluations with further CT imaging.8 Equivocal studies should prompt immediate evaluation with contrast-enhanced CT for determination of solid organ injury. Disadvantages of FAST are poor sensitivity in pediatric patients, interference because of bowel gas and increased adiposity, uncooperative patients, and ascites (Box 9-1).

Contrast Studies

Cystography and RUG are invaluable bedside diagnostic procedures for pelvic and suspected urethral injuries—for example, in the setting of hematuria, blood at the meatus, or a differential prostrate examination. Instilling contrast material with controlled pressure, and interval before and postvoid plain x-rays can reveal disruptions in the bladder and urethra.5 An intravenous pyelogram (IVP) confirms renal parenchymal, pelvic, calyceal, and ureteric integrity in the presence of hematuria and truncal trauma. Cystography reveals fine bladder detail better than IVP. If CT is indicated, IVP is redundant. IV contrast of 50 to 100 mL with plain film prior to laparotomy in penetrating injuries with hematuria yields detailed evaluation in the acute setting.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses