CHAPTER 8

The Smile and Facial Harmony

“Peace begins with a smile.”

—Mother Teresa

Orthodontics is both an art and a science. In addition to straightening the teeth, orthodontists create the smile. Although it is gradually becoming more of a science, orthodontics remains very subjective.

Orthodontic treatment involves many variables, such as growth patterns, muscular habits, and patient compliance. Certain time-tested requirements for long-term stability should be addressed during treatment planning. The goal is to place the teeth in particular positions that will produce the most functional, esthetic, and stable results possible.

Although the subject of this chapter is esthetics, a review of functional goals we discussed in earlier chapters is warranted. Throughout the history of orthodontics, certain truths have been found that set the standard for high-quality results. The challenge is to apply the new technology to create results that meticulous science has already proven possible. Several benchmarks have been established:

- It is important to control the position of the mandibular anterior teeth; uncontrolled flaring will certainly lead to posttreatment relapse.

- When the roots are not spread properly, mandibular lateral incisors tend to rotate and crowd.

- An expanded mandibular intercanine width typically constricts after the removal of retention.

- Insufficient torque in maxillary incisors tends to lead to overbite relapse.

- In cases of deep bite, the mandibular first molars should be uprighted and premolars extruded to level the arch and help prevent mesial drift of the arch.

- The anterior position of the teeth should be positioned so that the soft tissue profile allows the lips to touch gently when relaxed.

As the teeth are positioned in basal bone labiolingually, the clinician should also consider the way in which the lips frame the teeth. By beginning with the end in mind, the orthodontist can produce a symmetric smile1–3 while addressing these objectives. However, much information on the smile has been anecdotal to date.

To ensure creation of the best possible smile, at least 10 objectives should be addressed:

- Facial and dental midlines

- Tooth size

- Tooth angulation

- Cant of the occlusal plane

- Smile line

- Gingival line

- Buccal corridors

- Smile arc

- Finishing

- Tooth color

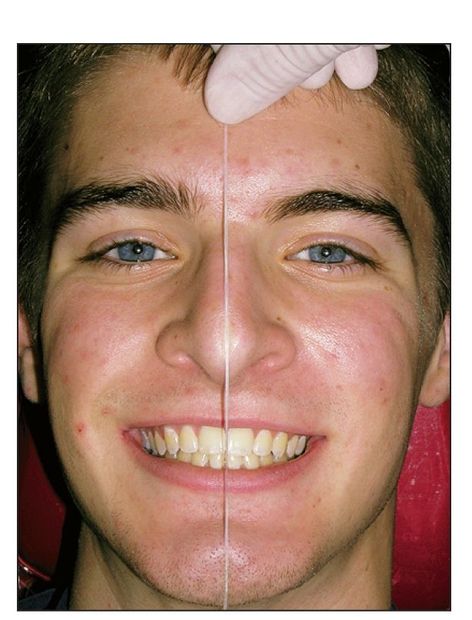

Fig 8-1 Determining midlines with dental floss is not always accurate. The results can be deceiving if other asymmetries exist. The upper lip is the best guideline.

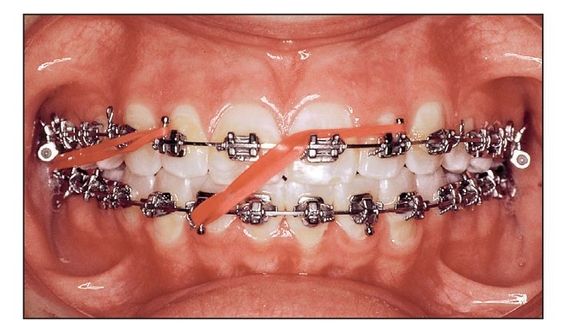

Fig 8-2 Midline elastic placed to correct a deviation.

Fig 8-3 (a) Pretreatment frontal intraoral view of a 29-year-old patient requiring unilateral premolar extraction. (b) Pretreatment facial view of the smile. (c) Posttreatment frontal intraoral view. The maxillary right first premolar has been extracted. Total treatment time was 26 months. (d) Posttreatment facial view of the smile.

Facial and Dental Midlines

The midline is observed by relating the facial midline and cupid’s bow of the upper lip to the maxillary central incisor midline. The mandibular dental midline is then matched with the maxillary midline (Fig 8-1).

Studies have shown that a slight deviation of the midline is not disconcerting to an individual’s appearance.1–7 Most midline deviations can be corrected after the finishing archwires are in place. Elastics are extended diagonally from a maxillary lateral incisor to the contralateral mandibular lateral incisor. The finishing archwire is a tied-back 0.0175 × 0.025–inch stainless steel (SS) wire in a 0.018-inch slot. A Class II or Class III elastic placed in the same vector is normally used (Fig 8-2). Severe midline deviations may require unilateral extraction, especially in adults (Fig 8-3).

Tooth Size

Tooth size is important for both dental and facial esthetics. Teeth should be proportionate to each other and proportionate to the face7–9 (Dawson T, personal communication, 2005).

When teeth are too small, the profile can be affected. The orthodontic patient is offered the opportunity to decide whether spaces should be left to allow future restorative enlargement of the teeth. For example, a 32-year-old woman had small maxillary incisors(Case 8-1). As a teenager, she had been treated with premolar extractions in another office. She was diagnosed as having a hyperdivergent growth pattern and symptoms of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction. Treatment included presurgical orthodontic alignment followed by a three-piece maxillary impaction osteotomy and augmentation genioplasty. A discrepancy in tooth size was noted in the maxillary lateral incisors, so space was created to enable cosmetic bonding after removal of the appliances.

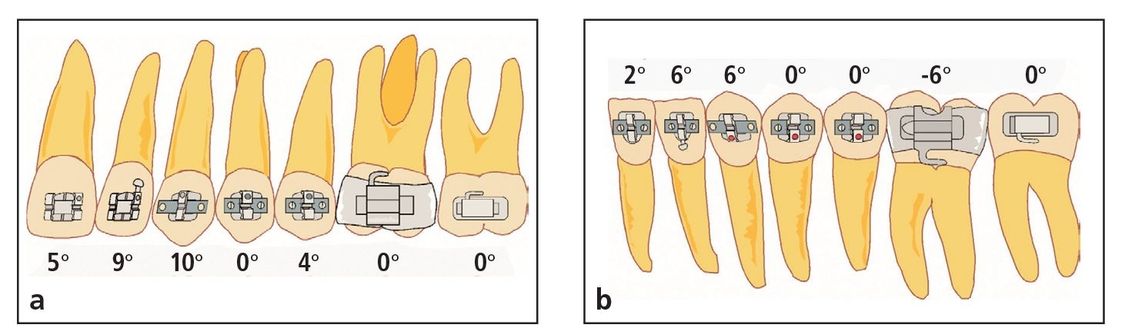

Fig 8-4 (a and b) Recommended bracket angulations for achieving an esthetic result.

Fig 8-5 Frontal view of occlusion after orthodontic treatment. Note the esthetic appearance of properly angulated teeth.

Fig 8-6 (a) Pretreatment frontal view of an unesthetic smile resulting from a canted occlusal plane, midline deviation, supernumerary maxillary left canine, and high lip line. (b) Pretreatment frontal intraoral view. (c) Posttreatment frontal view of the now esthetic smile. The excessive gingival display is a result of the short upper lip. (d) Posttreatment frontal intraoral view.

Tooth Angulation

The angulation of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth, canine to canine, has a dramatic effect on the patient’s appearance during smiling. Spreading the maxillary and mandibular anterior roots has been common in orthodontics at least since the beginning of the Tweed technique,10 when Tweed taught his students to use artistic positioning bends. Today these bends are incorporated in the design of the bracket prescription. If this prescription is followed, the teeth are not only more esthetically pleasing (Figs 8-4 and 8-5), but the author has also found them to be more stable.

Cant of the Occlusal Plane

Slight deviations in incisal plane symmetry have been shown to be less esthetic.4 This plane should be parallel to the upper lip and eyes (Fig 8-6). The cant of the occlusal plane usually can be corrected by the use of continuous symmetric archwires (not segmented), the application of symmetric forces (such as a cervical facebow), and the efforts of the patient to squeeze the teeth together to distribute symmetric occlusal forces.

Fig 8-7 Different smiles of the same patient show different amounts of gingival exposure. (a) Low smile line. (b) Normal smile line. (c) High smile line.

Smile Line

The smile line is the incisogingival position of the upper lip in relation to the maxillary anterior teeth when an individual is smiling. What is an ideal smile line?10 The stomion-incisor measurement represents the cephalometric position of the upper lip in relation to the incisal edge of the clinical crown.4 At rest, this distance should be about 4 to 5 mm. When an individual is smiling, the upper lip should be positioned within 2 mm above or below the gingival line. Normally, women have higher smile lines than men.11 This measurement decreases with age.

Diagnostically, the smile view taken during the examination of new patients is extremely important. Measuring smile lines visually, Tjan et al5 arranged smiles into three categories: low smile, average smile, and high smile. A high smile is one that reveals the total cervicoincisal length of the maxillary anterior teeth and a contiguous band of gingiva. An average smile is classified as a smile that reveals 75% to 100% of the maxillary anterior teeth and the interproximal gingiva. A low smile displays less than 75% of the anterior crowns.

The reality is that the same patient can demonstrate all three types of smile depending on how strongly he or she smiles and the patient’s mood during the records session (Fig 8-7).

Photographs of smiles can be very subjective. The goal is to obtain the biggest smile that the patient can give when the photograph is taken because the result can totally alter the treatment plan. To achieve this full smile in our office, we will ask the patient to smile and then tickle him or her behind the ear and say “Gucci Gucci.” It never fails to achieve the desired result.

Orthodontically, the smile line can be controlled or improved in growing patients. With good mechanics and favorable growth, impressive changes can be achieved. Attempts to intrude the maxillary anterior teeth in effect hold the teeth in place as the maxilla grows. Maxillary anterior teeth can also be extruded, tipped, or erupted with stable results.

VME with inadequate gingival exposure (nongrowing patients)

When the patient has inadequate gingival exposure, so that the maxillary incisors are not fully exposed when smiling (usually an open bite), treatment can also be successful without surgery. Typical elements of this procedure include: (1) extractions, if necessary; (2) a reverse curve in the maxillary archwire and possible accentuated curve in the mandibular archwire; (3) extrusion and tipping of anterior teeth; (4) tongue exercises; (5) squeezing exercises; and (6) up-and-down elastics.

Fig 8-8 (a) Pretreatment facial view of a 7½-year-old girl with VME and inadequate gingival exposure. (b) Pretreatment frontal intraoral view. (c) Posttreatment facial view. She was treated with a high-pull facebow and 2 × 4 technique in her mixed dentition phase. The second phase of treatment involved the use of typical mechanics. (d) Posttreatment frontal intraoral view. (e) Facial view 15 years posttreatment. (f) Frontal intraoral view 15 years posttreatment. Note the toothbrush gingival abrasion on the maxillary right canine.

The squeezing exercises are used in all high-angle cases and take advantage of the effects of isometric exercise on the muscles of mastication. The exercises consist of five 1-minute exercise periods per day. The patient is told to squeeze the teeth for 15 seconds and release, four times in a row. The exercise continues for at least 6 weeks.

A clinical study12 was conducted at Baylor College of Dentistry using 28 dental students. A period of 6 weeks of isometric (clenching) exercises produced the following results in the experimental group:

- Maximum bite forces increased 18% more than in the control group, which consisted of patients who did not perform any exercises.

- An increase in muscle strength was observed for the temporalis muscles.

- Resistance to fatigue was significantly increased.

A later study by Parks13 discussed masticatory exercise as an adjunctive treatment for hyperdivergent patients.

VME with inadequate gingival exposure (growing patients)

High mandibular angle malocclusions with open bite and tongue thrusting can be treated in two phases. In the mixed dentition, a high-pull headgear and 2 × 4 appliance technique are used (brackets on the central and lateral incisors and bands on the first molars). A reverse curve archwire is used to close the bite and control the skeletal pattern (Fig 8-8).

VME with excessive gingival exposure (growing patients with full dentition)

The treatment plan in a growing patient with VME is to inhibit or control vertical growth. The mechanics include a combination or high-pull facebow, archwires with an accentuated curve, and tongue-squeezing exercises.

Fig 8-9 (a) Pretreatment frontal facial view of a 16-year-old girl with small maxillary incisors and excessive exposure of the gingiva during smiling. (b) Posttreatment frontal view of occlusion. The central incisors and canines are at the same level, and the lateral incisors are slightly shorter. (c) Posttreatment frontal facial view after gingivoplasty.

In growing patients, treatment for severe gingival exposure during smiling usually involves the following protocol:

- Combination facebow

- First archwire: 0.016-inch nitinol (NiTi) continuous archwire

- Second archwire: 0.016-inch SS tied-back archwire with curve of Spee (the more gingival exposure during smiling, the greater the curve placed in the archwire)

- Third archwire: 0.0175 × 0.025–inch SS archwire with a gentle curve of Spee

Gingival Line

The gingival line is the relationship of the maxillary anterior teeth to the position of the gingival tissue covering them. The goal is to have the gingival margins of the central incisors and canines at the same level and those of the lateral incisors slightly shorter (Fig 8-9). Realistically, the orthodontist’s goal is to properly position the clinical crowns; usually the gingival line will adapt spontaneously. If crown-lengthening procedures are desired, the periodontist or restorative dentist can improve the gingival conditions after orthodontic treatment. Leveling the gingival line instead of the incisal edges is simpler than other crown-lengthening procedures.

The opposite extreme is for a patient to have a vertical maxillary deficiency that results in excessive overbite, low mandibular plane angle, and inadequate gingival exposure. The treatment plan in such a case is to extrude the maxillary dentition. The mechanics of treating vertical maxillary deficiency include placing a flat or reverse curve of Spee in the maxillary archwire. The overbite is corrected by leveling the mandibular arch. Often these patients also exhibit sagittal maxillary deficiency; thus, a face mask may be appropriate. In addition to moving the maxilla forward, by placing the force vector at a 45-degree angulation, the face mask can extrude the incisors vertically (Fig 8-10).

Fig 8-10 (a) Pretreatment frontal facial view of an 8-year-old girl with a Class III malocclusion and maxillary sagittal deficiency. The teeth and the gingiva are not exposed when she smiles. (b) Pretreatment frontal view of occlusion. (c) Two-year posttreatment frontal facial view after rapid palatal expansion and face mask treatment with full appliance therapy. (d) Frontal view of occlusion 2 years posttreatment.

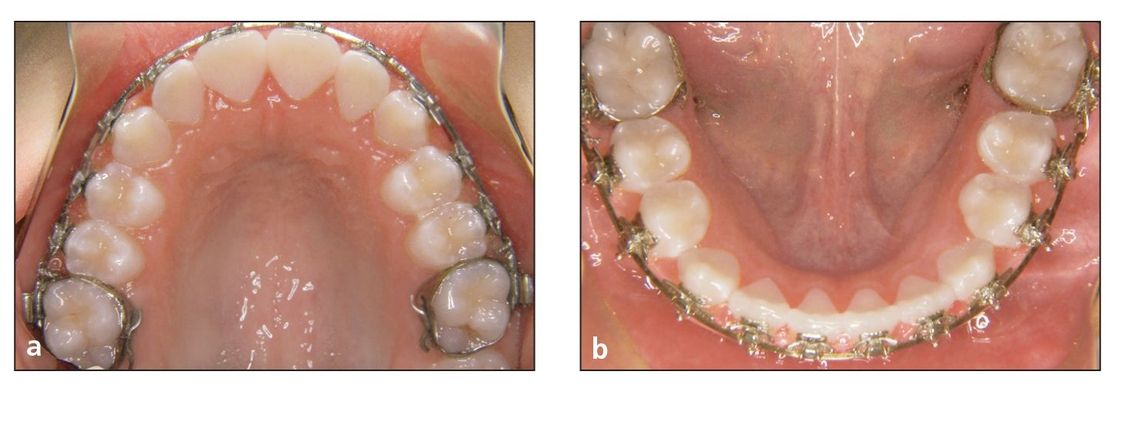

Fig 8-11 (a and b) The buccal corridors are controlled through intermolar and interpremolar expansion, mesiobuccal rotation of the maxillary first molars, proper tip and torque, and an ovoid maxillary arch form.

Buccal Corridors

Dark buccal corridors refer to the dark (negative) spaces created between the corners of the mouth and the buccal surfaces of the maxillary teeth during smiling.1 Johnson, 11 Bowman,14 and Mackley15 stated that the size of the buccal corridor showed no correlation to prior premolar extraction. They emphasized that patients with better esthetic scores had a significantly greater frequency of visible maxillary first molars. This confirms the author’s clinical experience.

To control the buccal corridors and prevent the creation of negative (dark) space, four objectives must be achieved (Fig 8-11):

- Adequate expansion in the premolar and molar regions

- Mesiobuccal rotation of the maxillary first molars per prescription to fill the buccal corridors with enamel and eliminate the dark spaces

- Proper tip and torque

- Development of an ovoid maxillary arch form

Fig 8-12 The position of the maxillary incisal edges in relation to the lower lip while smiling creates the smile arc.

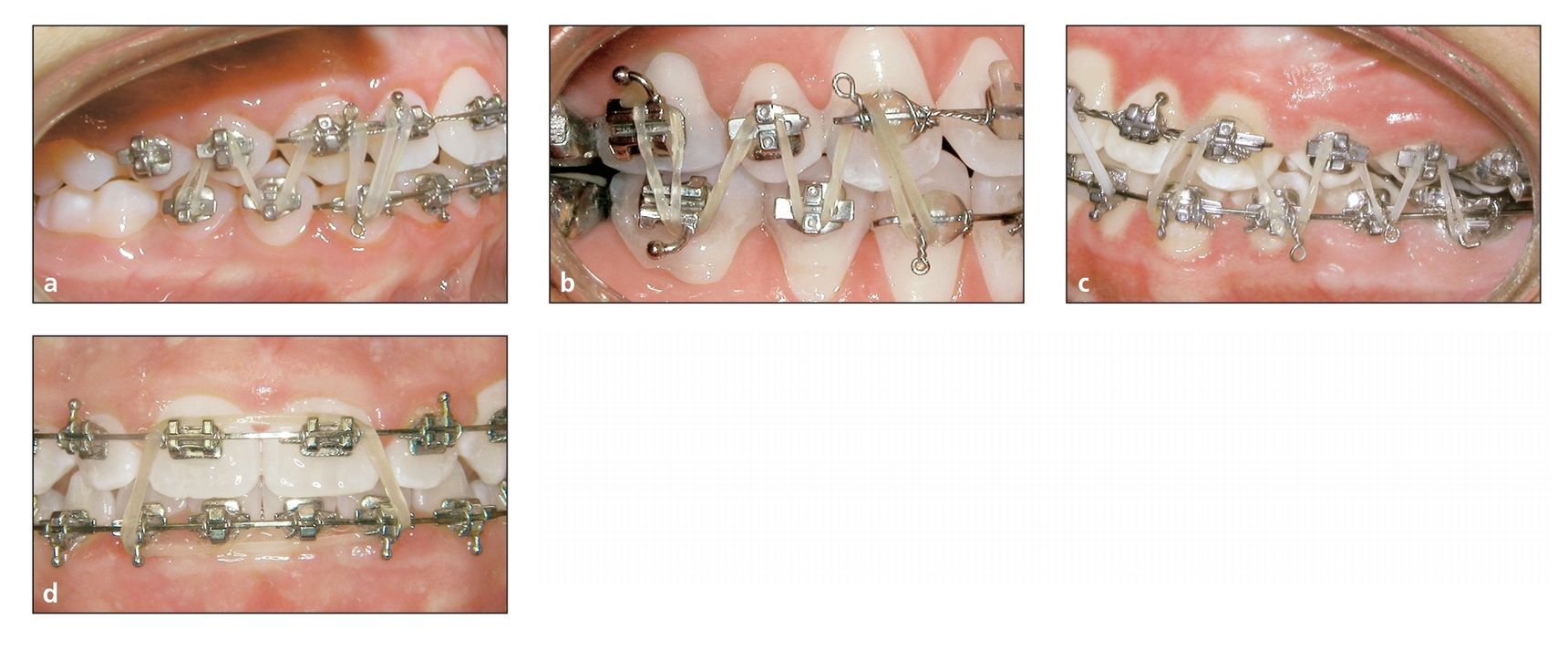

Fig 8-13 Final adjustment of the smile arc. The finishing elastic is a 0.75-inch, 2-oz elastic. (a) If the original malocclusion is Class II, the elastic attachment used is a W with a tail. (b) If the original malocclusion is Class III, the elastic attachment used is an M with a tail. (c) If the original malocclusion is Class I, the elastic attachment used is an M and one-half. (d) If the anterior overbite is deficient, anterior box elastics can increase the overbite. The anterior box elastic force used is a 0.1875-inch, 6-oz elastic. See Principle 16 in volume 1 of this series for more information.

Smile Arc

The position of the maxillary incisal edges in relation to the lower lip during smiling creates the smile arc (Fig 8-12). The ideal position for incisal edges is the wet-dry line of the lower lip. The smile arc is related to the incisal length and lip musculature. It is initially affected by bracket placement, archwires, and elastics. Ideally, the maxillary incisal edges should follow the curvature of the lower lip, resulting in parallelism.5,15

At the end of treatment, the smile arc can be adjusted with finishing elastics.16 I have used this procedure for more than 25 years. To begin this procedure, archwires are cut distal to the canines, and the posterior sections are removed. The arch sectioned depends on the original malocclusion. In patients with deep bite, the mandibular arch is sectioned; in patients with open bite, the maxillary arch is sectioned. In patients with a normal bite, either or both arches can be sectioned.

The finishing elastic is a 0.75-inch, 2-oz (Hawk, AO) elastic. If the original malocclusion is Class II, the elastic attachment used is a W with a tail (Fig 8-13a). If the original malocclusion is Class III, the elastic attachment used is an M with a tail (Fig 8-13b). If the original malocclusion is Class I, the elastic attachment used is an M and one-half (Fig 8-13c). This procedure allows the posterior teeth to settle into their final positions. As this is accomplished, the position of the maxillary incisors is observed. If the overbite needs to be increased, anterior box elastics can be used. These anterior box elastics are 0.1875-inch, 6-oz elastics (Tortoise, AO) (Fig 8-13d).

The smile arc is directly related to the overbite. How much overbite is necessary at the end of treatment to avoid posttreatment relapse? The goal is to have adequate anterior guidance so that immediate disocclusion of the posterior teeth occurs when the mandible comes forward. My experience, based on clinical observations, coincides with that of most orthodontists of the past; namely, the anterior bite should be overcorrected. Open bites should be overclosed, and deep bites should be opened beyond normal.

Usually, dentitions treated for deep bite will settle, causing the overbite to increase. Three different studies of long-term stability in my patients17–19 have demonstrated an increase in overbite that averaged slightly more than 0.5 mm (see Table 7-1). Although it is important that the maxillary incisors not be in a straight line relative to the lower lip, the eventual settling of the overbite should be considered when treatment is being finished.

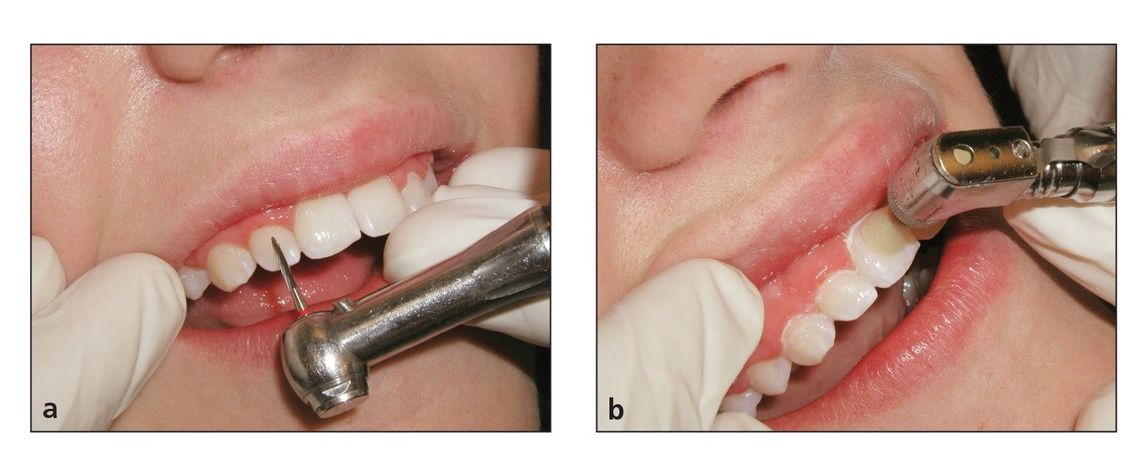

Fig 8-14 (a) Polishing bur. (b) Polishing cup.

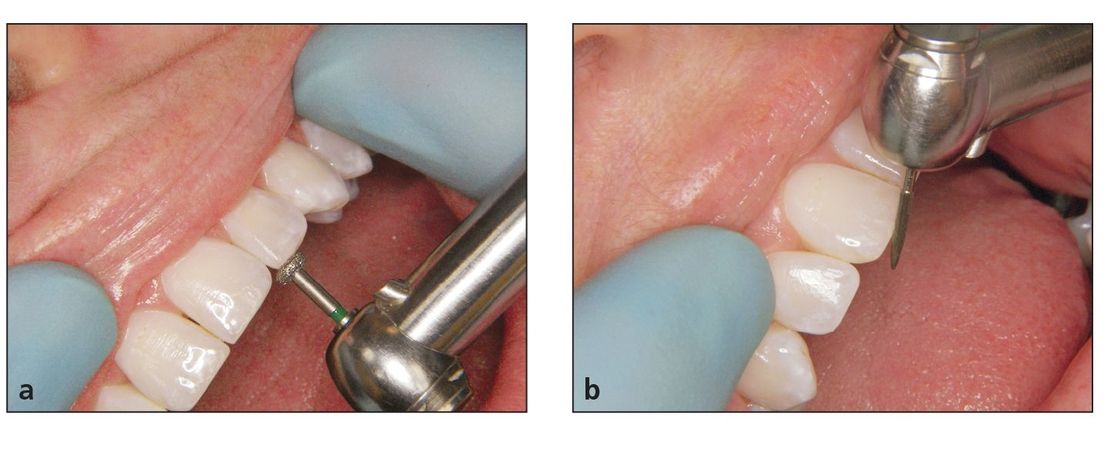

Fig 8-15 (a and b) Hollywood finishing for better incisal edges.

Finishing

The finishing touch also includes taking the extra step to polish the enamel with polishing burs and cups after bracket removal (Fig 8-14). In addition, the incisal edges are leveled with special diamond burs at the time appliances are removed (Fig 8-15).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses