Chapter 8

Problem Solving in Tooth Isolation, Access Openings, and Identification of Orifice Locations

Problem-solving issues and challenges in pulp chamber access addressed in this chapter are:

“The first step in the treatment of a tooth … is the adjustment of the rubber dam over the diseased tooth to preclude the possibility of the entrance of any germs in the oral secretions into the pulp chamber. This should be the invariable rule.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

“The first essential in getting at any root-canal is to gain direct access, and not to try to work around corners, whatever tooth-structure may have to be sacrificed.”

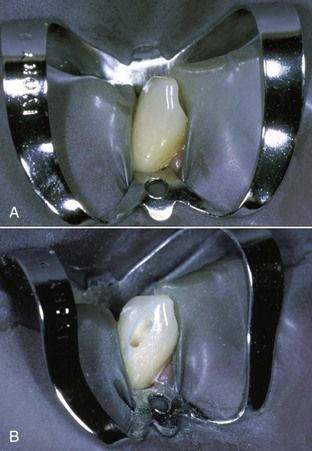

The main purpose of a lingual or occlusal endodontic access opening is to develop an unimpeded passageway to the pulpal space and apical foramen of the tooth. This unrestricted opening should be specifically designed for each tooth to facilitate proper canal cleaning, shaping, and obturation. In some cases, a problem-solving approach may dictate the need to initiate the access opening in a surface other than the lingual or occlusal (

FIGURE 8-2 A, Maxillary molar exhibits extensive buccal cervical erosion and abrasion. B, Initial access is made in a buccal-palatal direction without a dental dam. C, Closer view shows access after the canal orifices are opened.

The major consideration in all access openings is that coronal tooth structure should not be retained if its preservation prevents direct pathways to the canal orifices. This admonition does not imply that radical removal of the coronal tooth structure is necessary simply to obtain unimpeded access to the pulpal space; caution is also advised in creating excessively large access cavities for the convenience of operating microscope visualization. Rather, the statement implies that the clinician must be thoroughly knowledgeable about pulpal and external root anatomy and must be capable of proper radiographic assessment of the three-dimensional relationship of the pulpal space within the confines of the tooth.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

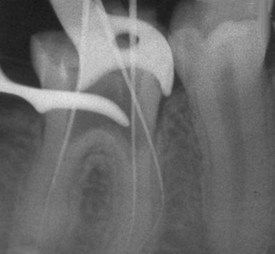

A 37-year-old female presented with acute pain to biting on her mandibular left first molar. Following diagnostic testing, a diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis with acute apical periodontitis was made. Root canal treatment was initiated on the tooth, and the final radiograph showed poorly filled canals with significant canal space apical to the gutta-percha filling in all canals (

Solution

An assessment of the tooth indicates that the roof of the pulp chamber had not been removed (see

Critical Factors in Tooth Isolation Within the Standards of Care

Proper tooth isolation is essential to all phases of root canal treatment, particularly patient protection and asepsis.

FIGURE 8-4 A, Maxillary premolar with subgingivally fractured palatal cusp. B, An oral sealing agent is placed along the palatal margin. C, A rubber dam is sealed in place. D, Clamping of adjacent teeth facilitates isolation of a tooth prepared for a crown. E, Two central incisors are isolated using two clamps. F, The tooth is isolated with excessive amounts of temporary material. This approach may prevent the necessary excavation and determination of restorability before root canal procedures. G, Temporary material adjacent to two mesial canals is used to isolate the tooth. Scraping the material with files and carrying it into the canal create a strong possibility of blocking the canal.

These are important issues because what is being taught in dental education may not be viewed seriously by the dental clinician once in practice.

There are several directives that should be considered for all cases of root canal treatment. Prepare access openings after a well-fitted and disinfected dental dam is placed, isolating the tooth to be treated. This is followed by disinfecting the dental dam with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite or alcohol before access to enhance asepsis (

Major Problems or Errors in Endodontic Access Openings

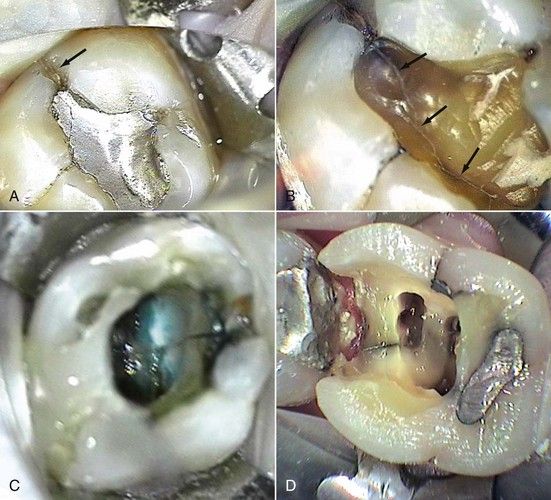

Many problems can occur during access opening preparation that will impact greatly on the subsequent phases of root canal treatment. Major shortcomings tend to occur in the following areas. First, all caries and unsupported weak tooth structure must be removed. This will enable the determination of tooth restorability and identification of any defects such as cracks (

FIGURE 8-6 A, Apparent small crack on the marginal ridge of a mandibular molar (arrow). B, Same tooth as in A after removal of the restoration. Note the crack line extending almost completely across the pulpal floor. This is an obvious cause of pulpal pathosis but may not be significant in treatment planning if it does not extend apically to the pulpal floor. C, Coronal fracture extending across the pulpal floor. Careful assessment of the periodontal attachment in this area should be done to rule out extension of the fracture below crestal bone. Note the use of Methylene Blue 1% to stain fracture line. D, Large crack on the mesial floor of cavity preparation in a maxillary molar. A large crack at the level of the gingival margin could easily extend apically below the level of crestal bone.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

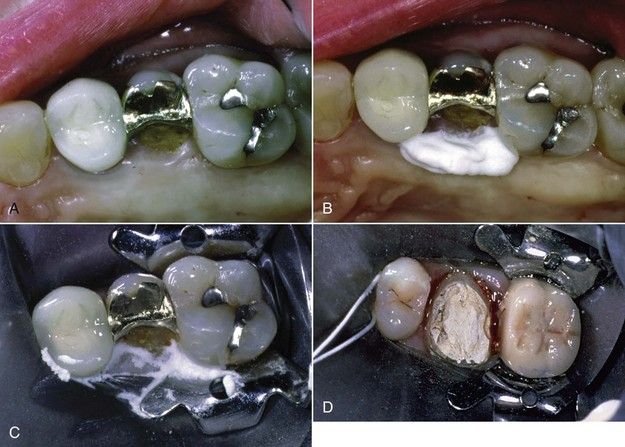

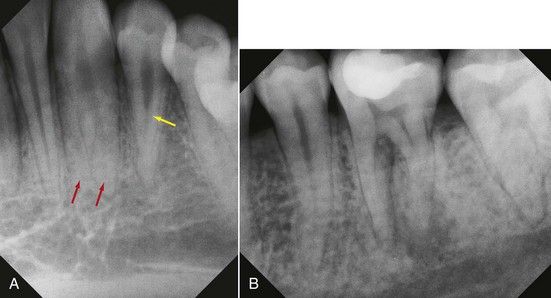

A 54-year-old male presented with episodic pain in the mandibular left quadrant. All teeth in this quadrant had extensive restorations. He believed his pain was coming from the first molar, but he was not sure. Pain was evident in response to percussion on the first molar; all other teeth responded normally. Cold elicited prolonged pain on the first molar, with normal responses on the adjacent and contralateral teeth. Periodontal probings and palpation were normal, but an explorer was easily placed under the mesial buccal margin of the crown on the first molar. A radiograph showed an invasive carious lesion on the mesial of the first molar, along with radiolucencies at the apices of both roots (

FIGURE 8-7 A, Radiograph showing apical lesions on both roots and recurrent caries under mesial margin of the crown. B, Cutting of the crown from the tooth. C, Crown has been removed, and decay is evident under the old restoration. D, Removal of the old restoration shows significant decay. E, Final excavation that allows for evaluation of the tooth structure and facilitates direct access to the pulp chamber.

Solution

All potential problems with gaining access to the pulpal space can be prevented with crown removal. In this case, the tooth was isolated, and the crown was cut off using a bur to cut a groove from buccal to lingual (see

During the removal of carious tooth structure, the peripheral decay is removed first, and then the carious material is removed inward toward the pulp chamber (

FIGURE 8-8 A, Caries around margins and under cusps must be excavated before the endodontic access opening is made. B, Excessive hemorrhage from inflamed pulp tissue can impair visualization of the pulp chamber.

Along with caries excavation, removal of unsupported tooth structure and weakened or faulty restorations enhances access to the canal system and visibility of tooth fractures (see previous Clinical Problem) and helps prevent fracture of fragile enamel walls and possibly the entire tooth during treatment

FIGURE 8-9 A, Maxillary molar requires root canal treatment. Exploration showed evidence of decay around distal margins of amalgam. B, Removal of amalgam reveals a vertical fracture on the palatal margin. C, Complete cleaning and shaping of canals are shown. Fracture lines are still visible, but no periodontal defects are present.

FIGURE 8-10 Crowned tooth with endodontic access opening is shown. All canals are visible when viewed from the occlusal perspective.

Oftentimes the crown of the tooth is not in direct alignment with the long axis of the root, so preparation of the access with only the angle of the crown in mind invites a coronal perforation or gouging of the crown. Teeth that normally exhibit significant altered crown-root angulations are maxillary lateral incisors and mandibular first premolars,

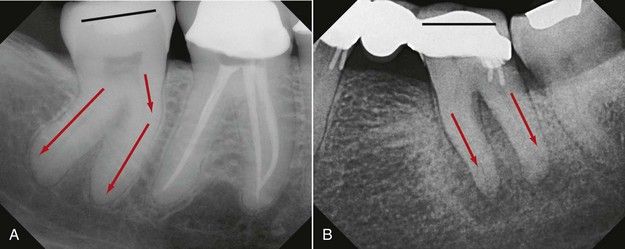

FIGURE 8-11 A and B, Two mandibular molars with the occlusal surface at divergent angles to the long axes of the roots. Occlusal surface orientations are indicated by the black lines on both teeth. Root angulations are indicated by the red arrows on both teeth. Penetration perpendicular to the occlusal surface may lead to ultimate chamber/furcation perforation.

Undermining and weakening coronal or radicular tooth structure is inevitable when anatomic relationships are not readily identified, even if a perforation does not occur. To compound this situation, extra canals are commonly found (

FIGURE 8-12 A, Both canine and lateral incisors have multiple canals. B, Distal roots of a mandibular molar with two distinct roots/canals.

Coupled with a smaller or calcified pulp chamber or canal, failure to take into account altered coronal-radicular relationships will usually lead to irreparable damage to the tooth structure (

FIGURE 8-13 Access perforation in a mesially tipped mandibular molar with calcified canal orifices. Access was cut through a large composite restoration. Despite its eventual removal, the clinician remained disoriented as to the location of the second mesial orifice. A preoperative bitewing radiograph might have established the true orientation of the long axis of the tooth with the occlusal plane.

Access openings in artificial crowns or excessively large restorations also invite possible perforation if the three-dimensional relationship of the pulp chamber in relation to the altered crown anatomy (due to restorations) is not considered.

Techniques for Safe and Accurate Access Cavity Preparations

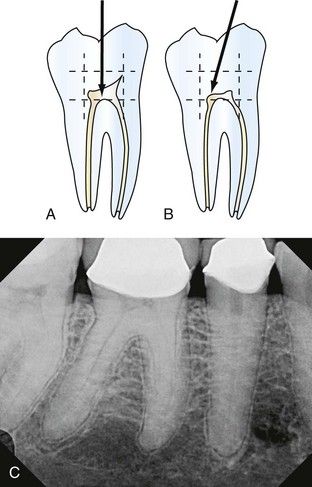

Access opening preparation is a dynamic, three-dimensional process.

FIGURE 8-14 A, Diagram of mandibular molar shows anticipated parameters of the pulp chamber. Access entry must proceed into the center of these parameters (arrow). B, Access entry may be directed to the largest canal (arrow) in cases of tooth misalignment, calcification, or lack of visible pulp chamber. C, With a crown in place and evidence of calcifications in the pulp chamber, a direct-line access opening into the center of this tooth is recommended.

FIGURE 8-15 A and B, Two molars requiring root canal treatment, each with pulp horns visible even in the presence of some calcifications. Once these pulp horns are reached with a bur, there is initial spatial confirmation of the pulp chamber location and dimensions.

FIGURE 8-16 Access opening in maxillary central incisor demonstrates straight-line access to the pulp space.

Complete removal of the lingual ledge will often uncover extra canals in mandibular incisors, canines, and premolars (

FIGURE 8-17 Access opening in mandibular incisor (A) extends lingually. The second canal located under the cingulum is noted. B, Two canals in a maxillary lateral incisor.

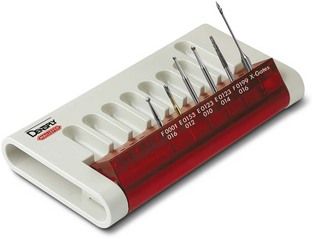

Burs that are recommended for access to anterior teeth include small to medium round burs, tapered diamonds and/or Endo-Z burs for refinement of the access outline, and possibly Gates-Glidden burs or X-Gates to assist in lingual ledge removal (

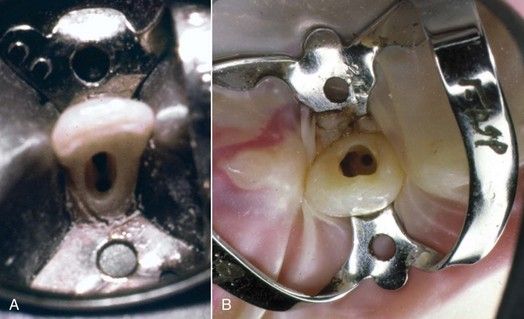

In posterior teeth, failure to remove the entire roof of the pulp chamber is a />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses