Pain Reaction Control

Sedation

The majority of pediatric dental patients can be treated in the conventional dental environment. By establishing good rapport with the patient and parent and by relying on sound behavior management techniques (see Chapter 23), the anxiety and pain of many pediatric dental patients can be managed effectively using only local anesthesia. In those children who are unable to tolerate dental procedures comfortably despite gentle encouragement and adequate local anesthesia, anxiety and pain control will have to go beyond communicative behavioral modification and physiochemical blockade of the anatomic pathways. Pharmacologic management is indicated for children who cannot be managed with traditional behavioral management techniques and local anesthesia.

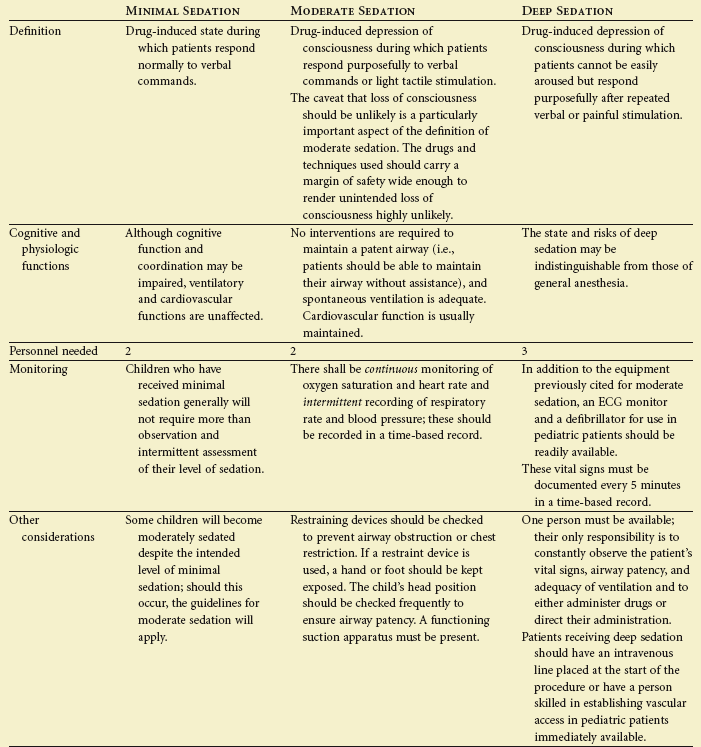

In 1985, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) jointly endorsed “Guidelines for the Elective Use of Conscious Sedation, Deep Sedation, and General Anesthesia in Pediatric Patients.”1 These guidelines set the current standard of care for those who practice these sedation techniques for pediatric patients. The most recent cosponsored guidelines using the definitions of minimal, moderate, and deep sedation appeared in 2006 and can be broadly summarized2 (Table 8-1).

Minimal and Moderate Sedation

Currently, the minimal monitoring requirements for moderate sedation are:

• Pulse oximeter for monitoring oxygenation and pulse rate (Figure 8-1, A)

• Blood pressure cuff for monitoring circulation (Figure 8-1, B)

• Precordial stethoscope or a capnograph to monitor ventilation (Figures 8-1, C and D). Observation of chest movements and continuous verbal communication are acceptable for moderate sedation, but because continuous verbal communication may be undesirable for the child patient, a precordial stethoscope or capnograph is usually required for moderate sedation and always required for deep sedation.

Minimal and Moderate Versus Deep Sedation: A Critical Question

Why is it a problem for the practitioner to move from the threshold of minimal and moderate sedation to deep sedation? The answer is simple: The patient has a much more frequent and serious risk of respiratory or cardiovascular complications during deeper levels of sedation. When the patient has a partial or complete loss of protective reflexes and cannot maintain an airway independently, hypoxemia, laryngospasm, pulmonary aspiration, and apnea may be serious or life threatening outcomes.3 Because the separation between moderate and deep sedation can sometimes be difficult to discern, it is the wise practitioner who obtains proper training in monitoring techniques and managing sedation before using pharmacologic management for children. Furthermore, the current guidelines indicate that the practitioner should be sufficiently trained to “rescue” the child should he or she enter a deeper level of sedation than that intended or otherwise become compromised. Although it is appropriate to activate Emergency Medical Services (EMS; call 911) in an emergency, the practitioner must not rely solely on the arrival and intervention of the EMS personnel. In other words, active intervention using basic or advanced life support must be accomplished by the practitioner and his or her staff while awaiting arrival of the EMS team. Management of the airway and ventilation is usually the most critical task to accomplish and master while awaiting the EMS team. Since the depth of sedation level is not always predictable, especially with oral routes of administration, the practitioner needs to be trained and able to rescue a child who enters a deeper level of sedation than originally intended or planned for the procedure.

For those practitioners who choose to practice deep sedation for pediatric patients, the guidelines are specific about requirements for a higher level of personnel training as well as a higher level of vigilance in monitoring the patient’s vital signs and level of sedation. They spell out requirements for personnel, the operating facility, intravenous access, monitoring procedures, and recovery care that carry a higher level of expectation and training than is the case with the use of minimal or moderate sedation.2 In short, for practitioners who choose to use deep sedation, the standard of care specified in the guidelines is nothing less than stringent, and it is doubtful that many general practitioners or pediatric dentists currently have the training or facilities to undertake deep sedation in an office setting.

Reliance on the Guidelines as the Standard of Care for Minimal and Moderate Sedation

The three standards in the guidelines that have most dramatically changed the manner in which pediatric sedation is practiced in the office setting relate to (1) personnel, (2) patient monitoring, and (3) preprocedural prescriptions. Relative to personnel, the guidelines specify that an assistant other than the dental operator must participate in the sedation procedure and that this assistant must be trained to monitor appropriate physiologic parameters and assist in any support or resuscitation measures required. Relative to intraoperative monitoring procedures during sedation, the guidelines specify continuous monitoring by a trained individual. A precordial stethoscope, blood pressure cuff, and pulse oximeter are considered the minimal equipment needed for obtaining continuous information on heart rate and respiratory rate.4,5

In summary, the guidelines have had a major impact on how the practitioner must approach the sedation of children. There are no systematic evaluations of the impact of the guidelines on safety in pediatric sedation; however, it is our opinion that these guidelines are having a dramatic impact in improving the safety of sedation in the dental office environment. Unfortunately, significant morbidity and mortality have occurred6–9; however, no deaths have occurred, to our knowledge, when the guidelines have been faithfully followed by the practitioner.

Routes of Administration

Inhalational Route (Nitrous Oxide)

Advantages

Nitrous oxide and oxygen administered with fail-safe dental delivery systems (Figure 8-2) produce minimal sedation or light moderate sedation. Loss of consciousness and/or the inability to maintain a patent airway are almost impossible to achieve. The primary advantages of nitrous oxide for sedation in pediatric dentistry are discussed in the following sections.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline TABLE 8-1

TABLE 8-1

FIGURE 8-1

FIGURE 8-1