Head and Neck Pathology

1. Infectious (e.g., bacterial, viral, fungal infections)

2. Traumatic etiology (e.g., irritation fibroma)

3. Neoplastic: epithelial, connective tissue, glandular, lymphatic, osseous, muscle, and vascular tumors, which can be characterized as benign or malignant. Metastatic disease to the head and neck, by definition, is malignant.

4. Immunologically mediated disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis)

5. Side effects of other medical or surgical therapy (e.g., osteoradionecrosis)

6. Cysts of the head and neck (inflammatory and noninflammatory cysts)

7. Pathologic processes related to the regional anatomy (e.g., sialolithiasis)

8. Congenital malformations (cleft lip and palate)

9. Degenerative disorders (osteoarthritis)

10. Iatrogenic (e.g., intraoperative damage to a cranial nerve)

Several of these categories are addressed elsewhere in this book. This chapter illustrates eight teaching cases, representing disorders of infectious, traumatic, neoplastic, anatomic, and idiopathic etiology, that are common in the oral and maxillofacial region. A teaching case discussing the differential diagnosis of a neck mass also is provided. The case that discusses osteoradionecrosis outlines the current controversies and management issues arising from this complex complication of head and neck irradiation. Drug-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws (DIONJ) was discussed in Chapter 2.

Pleomorphic Adenoma

Examination

There is a visible swelling in the right subauricular area that distorts the facial contour (Figure 7-1). Palpation reveals a well-circumscribed, freely moveable, firm, rubbery, 1- to 1.5-cm, nontender mass above the angle of the mandible. (Benign processes are typically slow growing and push, rather than infiltrate, local structures, such as the overlying skin; adjacent structures, such as blood vessels and nerves, are usually not involved). There is no warmth, erythema, ulceration, or induration of the overlying soft tissue (signs of an inflammatory or a malignant process).

Imaging

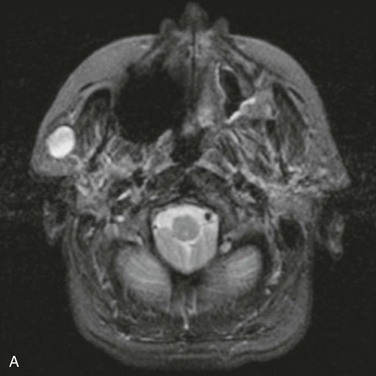

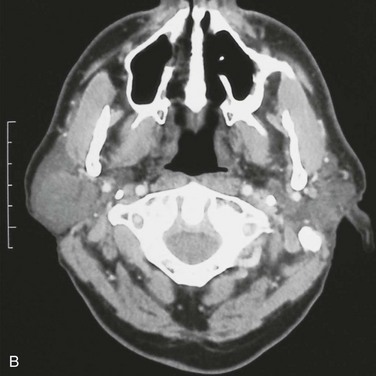

For the current patient, a panoramic radiograph confirmed no observable pathology. An MRI scan demonstrated a well-circumscribed mass within the substance of the parotid gland, measuring 1.5 cm in diameter, with no homogeneous enhancement (Figure 7-2). There was no evidence of enlarged intraparotid lymph nodes.

Differential Diagnosis

In the current case, the slow, circumscribed growth, lack of fixation, and absence of cranial nerve involvement or adenopathy associated with the lesion suggest a benign process. In addition, the absence of any erythema, pain, or warmth, together with a normal WBC count, implies a noninfectious/inflammatory process. With a swelling in this region, a differential for proliferative processes includes pleomorphic adenoma, subcutaneous lipoma, Warthin’s tumor, monomorphic adenoma, and malignant salivary gland neoplasms (Box 7-1).

Complications

Early complications can include facial nerve paralysis, hemorrhage, hematoma, infection, skin flap necrosis, trismus, salivary fistula, sialocele, and seroma formation. Long-term complications include Frey syndrome, hypoesthesia of the greater auricular nerve, tumor recurrence, and cosmetic deformity from the soft tissue defect (Box 7-2).

Discussion

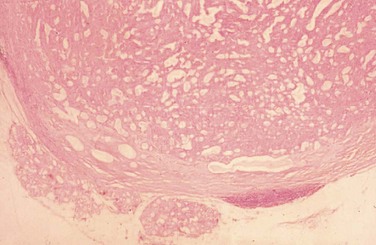

Histopathologically, permanent hematoxylin- and eosin–stained sections demonstrate typical histology, including glandlike epithelial cells forming nests, chords, and ductlike structures within a heterogeneous stromal background of myxoid, chondroid, and mucoid material, along with a distinct fibrous connective tissue lining (Figure 7-3).

Allison, GR, Rappoport, I. Prevention of Frey’s syndrome with superficial musculoaponeurotic system interposition. Am J Surg. 1993; 166:407–410.

Bankamp, DG, Bierhoff, E. Proliferative activity in recurrent and nonrecurrent pleomorphic adenoma of the salivary glands. Laryngorhinootologie. 1999; 78(2):77–80.

Garcia-Perla, A, Munoz-Ramos, M, Infante-Cossio, P, et al. Pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid in childhood. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2002; 30:242–245.

Hickman, RE, Cawson, RA, Duffy, SW. The prognosis of specific types of salivary gland tumors. Cancer. 1984; 54(8):1620–1624.

Howlett, DC, Kesse, KW, Hughes, DV, et al. The role of imaging in the evaluation of parotid disease. Clin Radiol. 2002; 57:692–701.

Jorge, J, Pires, FR, Alves, FA, et al. Juvenile intraoral pleomorphic adenoma: report of five cases and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002; 31:273–275.

Kwon, MY, Gu, M. True malignant mixed tumor (carcinosarcoma) of parotid gland with unusual mesenchymal component: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001; 125:812–815.

Nadershah, M, Salama, A. Removal of parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 2012; 24(2):295–305.

Salama, AR, Ord, RA. Clinical implications of neck in salivary gland disease. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin North Am. 2008; 20(3):445–458.

Schreibstein, JM, Tronic, B, Tarlov, E, et al. Benign metastasizing pleomorphic adenoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995; 112(4):612–615.

Shashinder, S, Tang, IP, Velayutham, P, et al. A review of parotid tumors and their management: a ten-year-experience. Med J Malaysia. 2009; 64(1):31–33.

Speight, PM, Barrett, AW. Salivary gland tumours. Oral Dis. 2002; 8:229–240.

Stanley, MW. Selected problems in fine needle aspiration of head and neck masses. Mod Pathol. 2002; 15(3):342–350.

Valentini, V, Fabiani, F, Perugini, M, et al. Surgical techniques in the treatment of pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: our experience and review of literature. J Craniofac Surg. 2001; 12(6):565–568.

Mucocele and Fibroma*

Examination

Intraoral. Examination reveals no pathology of the hard or soft palate, tongue, floor of the mouth, or buccal mucosa. A soft, 1-cm, painless mass is appreciated just inferior and medial to the right labial commissure (Figure 7-4). The mass is fluctuant, soft, and nontender with a bluish mucosal discoloration. There is some evidence of trauma to the mass from the adjacent dentition. The tissue overlying the mass has become fibrotic as a result of repetitive trauma.

Assessment

An excisional biopsy was performed under local anesthesia confirming the diagnosis of a mucocele.

Bahadure, RN, Fulzele, P, Thosar, N, et al. Conventional surgical treatment of oral mucocele: a series of 23 cases. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2012; 13(2):143–146.

Baurmash, H. Mucoceles and ranulas. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 61:369–378.

Bouquot, JE, Gundlach, KK. Oral exophytic lesions in 23,616 white Americans over 35 years of age. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986; 62(3):284–291.

Harrison, JD. Salivary mucoceles. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975; 39:268–278.

Ishimaru, M. A simple cryosurgical method for treatment of oral mucous cysts. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993; 22:353–355.

Jinbu, Y. Mucocele of the glands of Blandin-Nuhn: clinical and histopathologic analysis of 26 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003; 95:467–470.

Kopp, WK, St-Hilaire, H. Mucosal preservation in the treatment of mucocele with CO2 laser. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004; 62:1559–1561.

Mandel, L, Baurmash, H. Irritation fibroma: report of a case. NY State Dent J. 1970; 36(6):344–347.

Martins-Filho, PR, Santos Tde, S, da Silva, HF, et al. A clinicopathologic review of 138 cases of mucoceles in a pediatric population. Quintessence. 2011; 42(8):679–685.

Marx, RE, Stern, D. Oral and maxillofacial pathology: a rational for diagnosis and treatment. Carol Stream, Ill: Quintessence; 2003.

Neville, BW, Damm, DD, Allen, CM. Oral and maxillofacial pathology, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002.

Regezi, JA, Courtney, RM, Kerr, DA. Fibrous lesions of the skin and mucous membranes which contain stellate and multinucleated cells. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975; 39(4):605–614.

Regezi, JA, Sciubba, JJ. Connective tissue lesions. In: Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, eds. Oral pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:191.

Sela, J, Ulmansky, M. Mucous retention cyst of salivary glands. J Oral Surg. 1969; 27(8):619–623.

Acute Herpetic Gingivostomatitis*

Examination

General. The patient is an uncooperative, anxious boy in otherwise good health.

Intraoral. Multiple vesicles and ulcerations extend over the buccal and labial alveolar mucosa and dorsal tongue (Figures 7-5) (primary acute herpetic gingivostomatitis can affect both the keratinized and nonkeratinized mucosa, but recurrent infection preferentially involves the keratinized tissue). Ulcerations measure from 1 to 3 mm in diameter and are covered by a pseudomembrane and an erythematous border. The gingiva is erythematous and painful, and there is copious saliva production with drooling. The ulcers present as foul-smelling ulcers when they rupture due to the friable pseudomembrane.

Ajar, AH, Chauvin, PJ. Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis in adults: a review of 13 cases, including diagnosis and management. J Can Dental Assoc. 2002; 68(4):247–251.

Blevins, JY. Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis in young children. Dermatol Nurs. 2003; 29(3):199–202.

Fatahzadeh, M. Primary oral herpes: diagnosis and management. J N J Dent Assoc. 2012; 83(2):12–13.

McDonald, RE, Avery, DR, Weddell, JA, et al. Gingivitis and periodontal disease. In: Dean JA, Avery DR, McDonald RE, eds. Dentistry for the child and adolescent. ed 9. St Louis: Mosby; 2011:366–402.

Aphthous Ulcers*

Examination

General. The patient is a well-developed and well-nourished woman in no apparent distress.

Maxillofacial. There is no facial swelling or cervical lymphadenopathy.

Intraoral. There are multiple ulcerations at various stages of healing in the oral mucosa measuring 6 to 12 mm. Two ulcers at the right buccal mucosa appear to coalesce. There is also a 7-mm ulcer of the left lateral tongue. The lesions demonstrate a central zone of ulceration covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane that is surrounded by a varying degree of erythema along the margins. There does not appear to be any source of trauma in association with the ulcers (sharp dental restorations or fractured dental cusps). Figures 7-6 and 7-7 show examples of minor and major aphthous ulcers on the mucosa of the commissure and the palate.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses