7

Assessment of the Patient

A thorough and systematic history and examination of the patient will ensure that all relevant details are recorded so that the clinician can determine the following:

- Diagnosis

- Treatment plan

- Prognosis

The purpose of this chapter is to describe a systematic approach to this all-important stage preceding treatment. The significance of the information obtained is discussed more fully in other chapters of the book.

History

Reason for attendance

After noting personal particulars such as name, address, age and occupation, the clinician should record the concern or complaint in the patient’s own words. For example, if the patient says that the denture is loose, it may be positively misleading if the clinician records the comment as ‘the denture lacks retention’. The denture may, in fact, exhibit excellent physical retention but is being displaced by an uneven occlusal contact.

History of the present complaint

It is essential to obtain full details of any complaint. If, for example, the complaint is of pain in relation to a denture, the location, character and timing of the pain should be determined; relieving and aggravating factors should also be recorded. It is important to ascertain the relationship of the time of onset of the symptoms with the time that the present set of dentures was fitted.

If a denture is loose, it is necessary to enquire when the looseness was first noticed. If the denture has been worn satisfactorily for several years before trouble developed, it indicates that the dentures were initially satisfactory and that subsequent changes such as resorption of the residual ridges or wear of the occlusal surfaces are responsible for the problem. In this situation, it is essential – in addition to identifying the cause of the complaint – to note the good features of the denture, as it is usually sensible to replicate these in the replacement dentures.

On the other hand, if the looseness was present from the time the denture was fitted, the cause may be attributed to a basic design fault in the denture, to unfavourable anatomical factors or perhaps to the inability of the patient to adapt to dentures. Until an examination is made, it is not possible to distinguish between these causes.

Dental history

When obtaining a patient’s dental history, it is necessary to determine:

- when the natural teeth were extracted;

- the reasons for the extractions;

- the occurrence of any surgical complications;

- how many dentures have been worn subsequently;

- the degree of success or failure with the dentures.

This history can provide important information on the following:

- The rate of bone resorption. The history of tooth loss provides a basis on which to make an assessment of the current rate of bone resorption. If extractions were carried out in the previous few months, resorption will still be continuing at a rapid rate, so that if dentures are provided at this time they will soon become loose and require rebasing. The patient should therefore be warned of this likelihood. If, however, the teeth were extracted several years ago, the alveolar bone will have reached a relatively stable state and the life of a replacement denture will be considerably extended.

- Retained roots. If there is a history of difficult extractions, it is advisable to obtain radiographs in order to check for the presence and location of retained roots.

- The adaptive capability of the patient. Clues can be obtained as to the adaptive capability of the patient. For example, if three sets of dentures have been worn successfully over a period of 15 years, it may be assumed that adaptation has been satisfactory, whereas if the same number have been provided over the last 2 or 3 years – and each has been troublesome – the ability to adapt will be suspect. However, it is vitally important not to jump to conclusions and to put the blame on the patient until one is satisfied that the complaint cannot be related to defects in the design of previous dentures (see Chapter 2). It is thus a wise practice to ask the patient to bring all available sets of dentures when attending the initial assessment, as inspection of them can yield valuable clues and increase the accuracy of the diagnosis.

Medical history

Notes should be made of a patient’s past and present medical history that is relevant to future dental treatment. Information should include particulars of drug therapy and the name of the patient’s medical practitioner. A patient for whom sedatives and tranquillisers are being prescribed may have a reduced capacity in adapting to dentures, as may a person suffering from a protracted chronic disability. It should also be noted that many antidepressants and tranquillisers produce xerostomia. This condition may reduce the physical retention of a denture and may cause a generalised soreness of the denture-bearing mucosa. It has also been reported that certain antidepressants and tranquillisers may adversely affect the tonicity of the facial muscles and may produce facial grimacing and trismus or bizarre tongue movements.

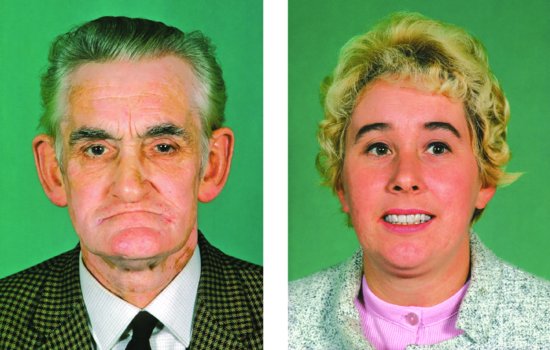

Figure 7.1 Both patients are wearing complete dentures which are in occlusion. The man shows obvious signs of a gross loss of occlusal vertical dimension; the freeway space is approximately 10 mm. On the other hand, the woman’s facial appearance leads one to suspect that the occlusal vertical dimension of her dentures is excessive.

It can be helpful when taking a medical history to work with a questionnaire to make certain that no significant aspect is overlooked.

Social history

When entering into a discussion with some patients, it may be helpful to explain that one is not being ‘nosy’ but that there are important reasons for such an enquiry. For example:

- A history of domestic worries may well tie in with the medication that has been prescribed or with a parafunctional habit which is resulting in pain under an existing lower denture.

- If the patient has been widowed, preparing food and eating alone can well take all the enjoyment out of mealtimes and an unbalanced diet could lead to tissue changes in the oral cavity.

- Because the clinician has a responsibility for the health of the patient, it is important to obtain information on risk factors related to oral cancer such as smoking or chewing tobacco, a high alcohol consumption, a prior history of cancer, familial or genetic predisposition. Age on its own is not a risk factor but exposure to other risks clearly increases with age.

Examination

Examination of the patient

Extra-oral examination of the patient

Simply by talking to the patient, and making careful observations at the same time, the clinician may obtain important information that will help in treatment planning:

- Discrepancy between actual and biological ages. Any discrepancy between the actual age and biological age should be noted as this can be important in assessing the likely adaptive capability, an aspect discussed more fully in Chapter 2.

- Skeletal relationship. The skeletal relationship of the patient should be assessed because this will indicate the appropriate incisal relationship of the planned dentures (Chapter 12).

- Occlusal vertical dimension. The facial appearance provides valuable information about the occlusal vertical dimension of existing dentures (Fig. 7.1). If loss of occlusal vertical dimension is noted, correction may be required before the provision of new dentures is started (p. 93).

- Dental appearance. If the patient already has dentures, the dental appearance should be evaluated at this stage of the examination. It is particularly important that the appearance of the dentures is assessed during speaking and smiling. Features such as inadequate lip support or poor appearance of the anterior teeth should be noted. If the patient has a complaint regarding the appearance of the current dentures it is essential that the details are carefully recorded when obtaining the history of the complaint.

- Extra-oral lesions. Inflammation and fissuring at the corners of the mouth (angular stomatitis) may be present; the significance and treatment of this condition are described on p. 119.

- Intolerance or other difficulties with the dentures. While the patient is speaking it may be possible to detect any obvious looseness of dentures, or whether the patient is having difficulty in controlling the prostheses.

Intra-oral examination of the patient

The broad objectives of this part of the examination are to determine:

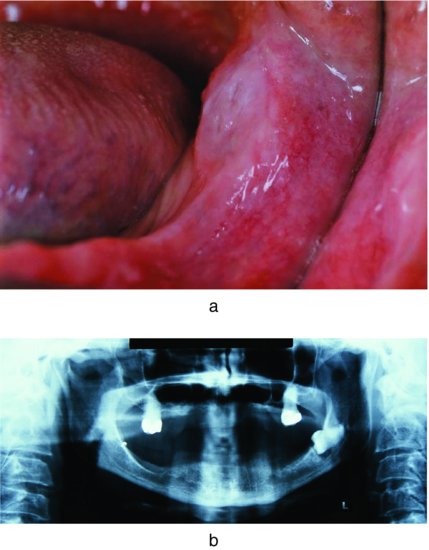

Figure 7.2 (a) The swelling in the left molar region should be reviewed for associated pathology. (b) A radiograph showed an unerupted third molar.

- whether there is any pathology in the mouth (Figs. 7.2a and 7.2b);

- what the prospects are for the new dentures providing a satisfactory level of comfort and function.

Detecting systemic disease

The mouth has been aptly described as a mirror which reflects the state of health of the individual. When systemic disease develops, the powerful combination of microorganisms, normal wear and tear, and moisture and warmth present in the mouth frequently result in visible changes in the oral tissues before signs of disease are evident elsewhere in the body. Investigation of these changes may allow an early diagnosis of the systemic condition to be made. For example, there may be a change in the population of papillae on the tongue; this change occurs first on the tip and sides, the areas of maximum trauma. The filiform papillae are progressively lost so that the fungiform papillae become more noticeable and produce the appearance of a ‘pebbly’ tongue; eventually, the fungiform papillae also disappear and the tongue becomes smooth (Fig. 7.3). These changes should lead the clinician to suspect deficiencies such as iron, vitamin B12 and folic acid. Diagnosis may be confirmed by the appropriate haematological investigations.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses