The Acute Phase of Treatment

The acute phase of care incorporates diagnostic and treatment procedures aimed at solving urgent oral problems. Acute care can involve a myriad of services from controlling pain and swelling to simply replacing a broken tooth on a denture. All types of patients may need acute care, including those under active treatment, on maintenance recall, new to a dental practice, or returning to a practice after being away for some length of time. Most people expect a dentist to be available to treat their immediate problems and are drawn to offices that provide such services. Good practice management and professional responsibility require that every dentist effectively and efficiently manage patients who have immediate treatment needs without unnecessary disruption to the flow of the practice. The dentist is also responsible for managing his or her patients when they have acute problems outside of normal office hours.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide information about how to design, record, and execute the acute phase of a dental treatment plan. In the course of this discussion, the reader will become acquainted with the unique challenges of providing acute dental care. The profile of the acute patient’s typical problems is described. Guidance is provided for evaluating, diagnosing, treating, and providing follow-up care for this patient. In addition, suggestions for documenting all aspects of acute care are presented.

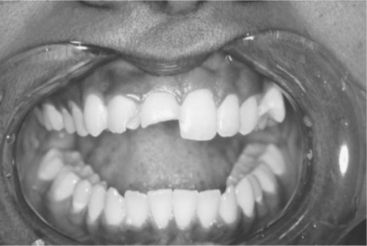

Two related terms are used throughout this chapter. An emergency problem incapacitates the patient and has the potential to become a life-threatening condition. In such a case, immediate attention is required for health reasons. Examples include severe dental pain, swelling, systemic infection, or trauma to the face or jaws. The dentist usually sees patients with emergency needs on the same day that contact is made. In contrast, an urgent problem does not require immediate attention for health reasons, but is a problem that the dentist or, more commonly, the patient thinks should be attended to “now” or “soon” (Figure 6-1). Examples include mild to moderate pain without active infection, asymptomatic broken teeth, lost restorations, and other purely esthetic problems. Treatment of urgent problems can, theoretically, be postponed without causing the patient unnecessary pain or the risk of systemic illness. Often these problems can be managed with palliative care, for example, treating the pain, but not the underlying problem, until the patient can be conveniently worked into the office schedule.

Figure 6-1 Although not painful, the fracture of the right central incisor is an urgent problem that needs prompt attention.

Making the distinction between an emergency and an urgent problem is important to the dentist and to the patient to ensure that no true patient health problem goes unattended. On another level, the experienced dental practitioner recognizes that the distinction may become irrelevant in the mind of a distraught, anxious patient. From a practice management perspective, it is important that the office be able to accommodate patients with acute needs in a timely and attentive manner, regardless of whether a potentially serious health issue exists. Not infrequently, patients have questions about “new” findings in the oral cavity that they fear may be cancer, or they may develop esthetic problems that for reasons relating to personal appearance and self-esteem need immediate attention. These concerns, although not true emergencies, do require the dentist’s recognition, if only to reassure the patient and to reschedule for definitive care.

Challenges

Treating patients with acute care needs can be challenging to the dentist in many ways. Initially the practitioner must determine whether the patient’s complaint is a true emergency requiring immediate attention or an urgent problem that can be treated at a more convenient time. Usually this discussion occurs over the telephone and may be resolved by an office staff member without the dentist’s direct involvement. On the other hand, the dentist usually manages after-hours emergencies. Once the decision has been made to see the patient, enough time must be available in the dentist’s schedule to adequately diagnose and treat the patient’s problem. This can be difficult when the practitioner’s day is tightly scheduled. Some busy practices reserve time in the dentist’s schedule, or book the schedule lightly, to accommodate occasional add-on appointments.

Arriving at a diagnosis and an acute care treatment plan can be time consuming. This problem is compounded significantly when the acute needs patient is new to the practice. In the absence of an existing health and dental history and an established relationship with the patient, the dentist must work without many of the usual clues or cues that would otherwise guide the process. The dentist needs to assess for the first time the patient’s health history, perform a limited oral examination and diagnostic tests, obtain radiographs if necessary, decide on the appropriate treatment, and execute some level of care to alleviate symptoms. Difficult enough for a patient of record, this task can be extremely challenging when it involves an anxious and emotionally labile patient whom the dentist has not met before.

During the initial appointment, the amount of time available to develop rapport is limited. If the patient is in significant pain or has been awake all night, he or she may not be thinking rationally. As a result, the dentist may have difficulty communicating the nature of the problem and the treatment options to the patient. The patient may have difficulty making a treatment decision or providing informed consent, especially for irreversible procedures, such as extractions or endodontic therapy.

Furthermore, it is common for some patients, especially those who have never been seen in the practice before, to expect to have an acute need managed immediately and simply. These individuals may have experienced a lifetime of episodic dental care, may not understand the nature of the problem, and may be unrealistic about the scope or complexity of the needed treatment. This can be frustrating for some practitioners, who see such patients as demanding and intrusive, and at the same time unappreciative of the value of comprehensive dental care. Nevertheless the dentist has the obligation, insofar as is possible, to educate the patient about his or her overall oral condition and to describe a vision for the way in which the emergency or urgent care treatment fits into the context of the person’s overall oral health. To help the patient understand and accept this vision, the dentist must be a good listener, take the time to explore all reasonable treatment options with the patient, and thoroughly discuss any barriers to treatment that the patient might perceive, especially with regard to time, finances, and pain. To accomplish this quickly, efficiently, and professionally and to do so with a personalized and caring delivery can be difficult for even the most experienced practitioner.

Rewards

Efficiently managing the patient with acute problems is essential to attracting new patients and to serving the needs of patients already in the practice. Dentists who can treat emergency and urgent problems in a timely manner will retain patient loyalty and see their practices grow. Relieving pain or restoring a broken tooth can also provide great personal satisfaction to the dentist. Often, patients with such problems arrive fearful and unsure of what treatment will be required. A kind, empathetic approach to care and prompt resolution of the dental problem may persuade some patients who present only for episodic treatment to become comprehensive care patients.

PROFILE OF THE PATIENT REQUESTING IMMEDIATE TREATMENT

Comprehensive Care Patient

Patients expect that their family dentist will see them promptly if they are in pain, break a tooth or prosthesis, or lose a temporary restoration. Such problems can sometimes be anticipated, or they may come as a surprise to both patient and provider. Even when the problem is anticipated, the timing for the event cannot be predicted with certainty.

Patients who are new to the practice and request comprehensive care for many dental problems may require immediate treatment, often to control or prevent dental pain. When planning treatment, it is possible to identify those urgent problems that are likely to become dental emergencies and to sequence them early in the treatment plan. For example, the patient whose tooth has significant decay and is experiencing prolonged sensitivity to heat may require immediate caries removal and a pulpectomy to avoid the possibility of increased pain and the development of an apical infection. Other common urgent care procedures include repairing prostheses or replacing restorations, especially in esthetic locations or when a tooth is sensitive.

Acute care may also become necessary when a patient is undergoing active treatment. Many procedures in dentistry have associated postoperative complications, such as pain, bleeding, or swelling. Experienced dentists are aware of the complications associated with the procedures they perform and discuss the chances for postoperative problems with the patient when treatment is rendered. If a problem arises, the dentist may only need to speak with the patient on the telephone; however, if the problem is more serious, the person may need to return for evaluation.

Patients on periodic recall may also develop urgent treatment needs. The problem may be related to prior treatment (e.g., pain from a tooth that received a restoration near the pulp) or to a chronic condition, such as a deep periodontal pocket that has become a periodontal abscess. Common complaints include sensitive or chipped teeth, lost or fractured restorations, broken prostheses, oral infections, and traumatic injuries. These issues require prompt attention to satisfy patient expectations.

Past patients of record who have not been seen for some time require special consideration during an examination for acute care problems. The dentist should determine if other dentists have provided treatment since the patient left the practice and if the patient has been receiving maintenance care on regular basis. The patient’s health questionnaire will need to be updated or redone.

Limited Care Patient

About 50% of the U.S. population uses dental services on a regular basis. Included in this group are those who receive at least an annual oral evaluation and maintenance procedures for the teeth and prostheses. For the remainder of the population, dental care is usually both episodic in nature and limited in scope. There are several reasons for this. Many individuals are afraid of receiving dental services, often because of unpleasant past experiences with a dentist and fears that treatment will be painful. Understanding the reasons for this anxiety and treating the fearful patient are discussed further in Chapter 13. For many, a real or perceived lack of financial resources to pay for dental treatment represents a significant barrier. For the elderly person or the individual with severe health problems, dental treatment may not be accessible or may be considered a low priority when compared with more life-threatening concerns. For some persons, dental care and good oral health simply are low priorities (see Chapter 17). These patients may appear apathetic, be reluctant to commit to a comprehensive treatment approach, may miss appointments, and ultimately may disappear from the practice all together (see the What’s the Evidence? box on p. 116). Lastly, some young persons may have had regular care in their youth, but have not yet taken responsibility for maintaining oral health as an adult. Often, for these individuals, making the time or even remembering to see a dentist regularly constitutes the biggest barrier to care.

Although the persons just described may not be regular visitors to a dental office, they will need treatment sometime in their lives. Most often, a particular event has provoked the patient to action. For example, a molar tooth, sensitive to hot and cold for several months, has now become a constant throbbing problem. For others, especially those who believe they are in reasonable dental health, the symptoms may be less acute but disturbing all the same. Common complaints include loose teeth, bleeding gums, hot or cold sensitivity, fractured teeth or restorations, or broken prosthodontic work. Fear of worsening pain or the anticipation of additional dental problems may also motivate these persons to seek dental treatment.

Culturally the U.S. population places a high value on personal appearance. For many, self-esteem can be greatly affected positively or negatively by the appearance of the teeth and smile. As a result, many limited care patients seek dental services because of esthetic concerns. Often, encouraged by friends and family to see a dentist, the patient may believe that he or she needs to look better to improve social and business opportunities. For such patients, a dark or missing anterior tooth may be perceived as a more severe problem than the broken down or chronically infected posterior teeth also discovered during examination (Figure 6-2).

PATIENT EVALUATION

The evaluation of the acute care patient requires the same components as for the patient seeking comprehensive care: the patient history, the physical and clinical examination, radiographs, and any necessary special diagnostic tests. However, each component is handled differently with the acute care patient. Of necessity, the acute care evaluation often is more abbreviated, although in some cases additional diagnostic procedures are performed. With any acute care patient, the findings, both positive and negative, take on a different and often increased level of importance because of the urgency of the situation.

Patient History

Methods and techniques for obtaining a comprehensive patient history are described in Chapter 1. The content of the acute care patient’s history focuses on issues that affect the diagnosis and management of the immediate problem or problems for which the patient has sought treatment. As a result, the health history questionnaire used for the acute patient history may be shorter than that used for the comprehensive care patient. (See Chapter 1 for a discussion of the inquiry process used to review the health history information with the patient.) The clinician realizes that many new patients who are in pain at the first visit also are anxious and may not be communicating or thinking clearly. Many of the issues discussed in Chapter 13 relating to the evaluation and treatment planning for the anxious patient also apply to the patient with acute care needs.

Chief Concern and History of the Concern

The chief concern, also referred to as the chief complaint, is the immediate reason for which the patient seeks treatment. It is usually best to record the concern in the patient’s own words, thereby capturing not only the issue that needs attention, but also the patient’s perception of the problem. The way in which the patient phrases the concern can provide important insight into the patient’s dental knowledge and awareness. As illustrated in the In Clinical Practice box, the patient’s words may also give the dentist a glimpse into the patient’s covert fears. As the starting point for investigating the patient’s problem, articulation of the chief concern is critical to making an accurate diagnosis of the acute problem. A clear, concisely stated chief concern helps the patient and dentist focus on the important issues and saves considerable time in the evaluation process. However, even a vague or poorly focused chief concern can trigger questions that enable the dentist to begin the process of establishing possible diagnoses.

The history of the chief concern enriches the dentist’s understanding of the primary problem and the way in which it arose (Box 6-1). More importantly, the history helps the dentist develop a short list of possible diagnoses and to discern what should be examined, what radio-graphic images should be taken, and what clinical tests should be performed to identify the source of the problem.

With about 90% of acute care problems, the careful and astute practitioner can make a tentative diagnosis from the chief concern as expressed by the patient and the related history. However, a dilemma arises if the patient is allowed to ramble, raising multiple complaints and symptoms. The dentist may become distracted and have difficulty arriving at the essential working diagnosis and, more importantly, treatment for the primary problem may be delayed as a result. On occasion, however, the patient’s seemingly unrelated concerns may provide important clues to the diagnosis, helping the dentist to make a treatment recommendation more quickly and accurately. Discerning when these other issues are important and when they are a distraction takes considerable experience, sensitivity, and skill.

Health and Medication Histories

Although the health history for the acute care patient is typically abbreviated, it cannot be overlooked. A prime cause for dental malpractice litigation has been the failure of dentists to gather and document an adequate health history for acute care patients (Box 6-2). As with the health history for the nonacute comprehensive care patient, the health history for the acute patient may be gathered through an oral interview, a health questionnaire, or a combination of both questionnaire and interview. For the patient of record who presents with an acute problem, an update of the existing health history usually is sufficient.

The dentist must investigate any positive patient responses and document significant additional findings in the patient’s record. Some patients who do not visit the dentist regularly may not see a physician either. The dentist is responsible for determining that there are no systemic health limitations or contraindications to dental treatment before performing any invasive examination procedures or before performing treatment on the patient. If the dentist cannot make that determination, it may be necessary to consult with the patient’s physician before proceeding.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses