6 MOUTH PREPARATION

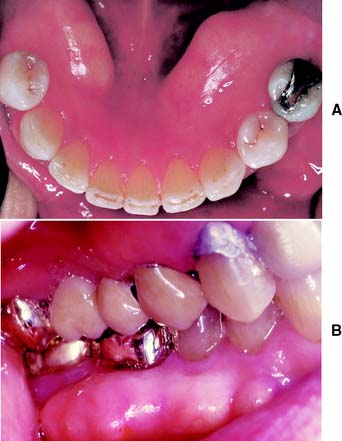

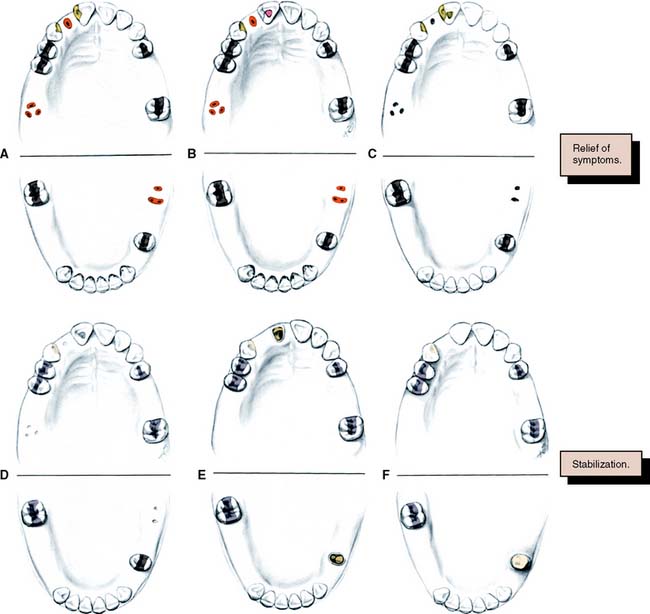

Fig. 6-1 Sequence of treatment. A, The patient has pain that seems to originate from the maxillary right central incisor. In addition, several teeth are missing, and retained roots, caries, calculus, and defective restorations are present. B, Relief of the acute problem by endodontic treatment of the incisor. C, Removal of deposits and unrestorable teeth. D, Caries are controlled, and defective restorations are replaced. The progress of ongoing disease has been halted. E, Endodontic treatment is undertaken, and post and cores and an interim restoration are placed. F, Definitive periodontal treatment is performed. G, Teeth are prepared for the final restoration. H, The fixed restorations are completed. I, Active phase of the treatment has been accomplished. Note that predictable management of complex prosthodontics involving fixed and removable dental prostheses can be facilitated by adopting the technique described on p. 102.

However, the sequence of preparatory treatment should be flexible. Two or more of these phases are often performed concurrently. Carious lesions or defective restorations often prevent proper oral hygiene measures, and their elimination or correction must be a part of preparatory treatment. If caries control results in a pulpal exposure or exacerbates an existing chronic pulpitis, endodontic treatment may be needed earlier than anticipated. When the primary symptoms have been eliminated, the occlusal needs of the patient are carefully evaluated through clinical examination and the study of articulated diagnostic casts. Extensive treatment of both arches simultaneously may be beyond the scope of the nonspecialist, and the use of cross-mounted diagnostically mounted casts should be considered (see p. 102). This enables treatment of each arch to be accomplished predictably and independently. Only when preparatory occlusal treatment is completed will the patient be ready for definitive restorative care.

ORAL SURGERY

Soft Tissue Procedures

Elective soft tissue surgery may include alteration of muscle attachments, removal of a wedge of soft tissue distal to the molars, increase of the vestibular depth, or modification of edentulous ridges to accommodate fixed or removable partial prostheses (Fig. 6-2).

Hard Tissue Procedures

Tuberosity reduction (Fig. 6-3) is also common, especially when there is inadequate space to accommodate a prosthesis. Although maxillary or mandibular tori (Fig. 6-4) seldom interfere with the fabrication of a fixed partial dental prosthesis, their excision may make it easier to design a removable partial dental prosthesis and occasionally improves access for oral hygiene measures.

Orthognathic Surgery

Candidates for orthognathic surgery require careful restorative evaluation and attention before treatment. Otherwise, an expected improvement in the facial skeleton may be accompanied by unexpected occlusal dysfunction. After surgery, the connection between plaque control, caries prevention, and periodontal health should be stressed to the patient.

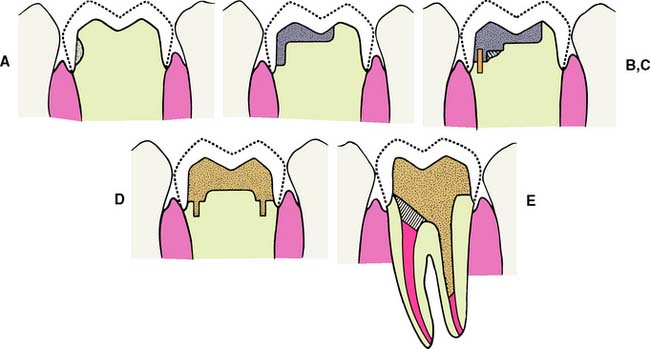

CARIES AND EXISTING RESTORATIONS

Crowns and fixed dental prostheses are definitive restorations. They are time-consuming and expensive treatment options and should not be recommended unless an extended lifetime of the restoration is anticipated. Many teeth that require crowns are severely damaged or have large existing restorations. Any restoration on such teeth must be carefully examined and a determination made regarding its serviceability. If doubt exists, the restoration should be replaced. Time spent replacing an existing restoration that in retrospect might have been serviceable is a modest price to pay for the assurance that the foundation will be caries free and well restored. Studies have shown that accurately detecting caries beneath a restoration without its complete removal can be very difficult.1–3 Even on caries-free teeth, an existing restoration may not be a suitable foundation. Preparation design is different for a foundation than for a conventional restoration, particularly with regard to the placement of retention. In general, when a crown is needed, the dentist should plan to replace any existing restorations. Although most teeth in need of restoration require foundation restorations, small defects resulting from less extensive lesions can often be incorporated in the design of a cast restoration or can be blocked out with cement (Fig. 6-5). The latter is recommended on axial walls where an undercut would otherwise result. If a small defect is present on the occlusal surface, however, it may be better to incorporate it into the final restoration than to block it out. The difficulty, of course, is anticipating this during the preparatory phase of treatment. Assessment is more difficult when an existing crown or fixed dental prosthesis is being replaced. In that case, the extent of damage can be seen only after the defective restoration has been removed.

FOUNDATION RESTORATIONS

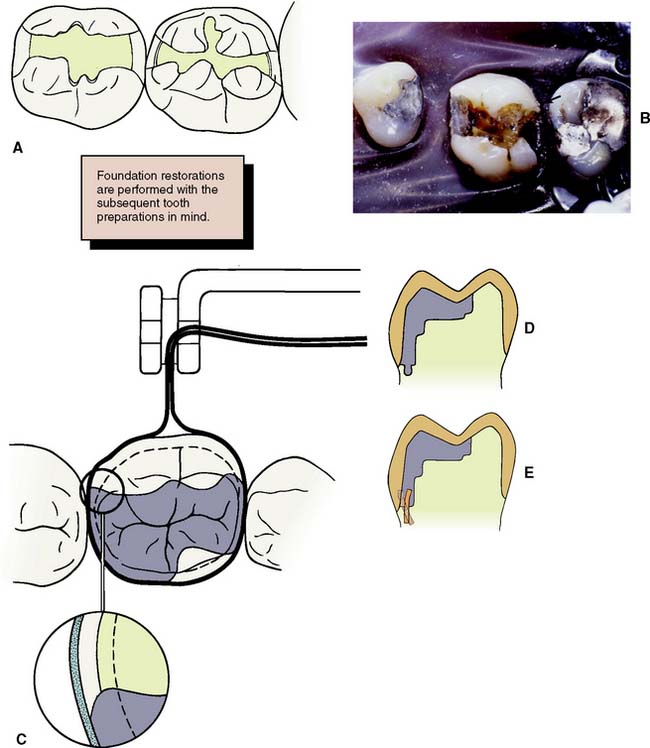

A foundation restoration, or core, is used to build a damaged tooth to ideal anatomic form before it is prepared for a crown. With extensive treatment plans, the foundation may have to serve for an extended time. It should provide the patient with adequate function and should be contoured and finished to facilitate oral hygiene. Subsequent tooth preparation is greatly simplified if the tooth is built up to ideal contour. Then it can be prepared essentially as if it were intact. Guide grooves can be used to facilitate accurate occlusal and axial reduction (see Chapter 8), and the preparation design will be consistent from tooth to tooth. The skills learned preparing preclinical mannequins with “ideal” teeth can be readily transferred to clinical practice.

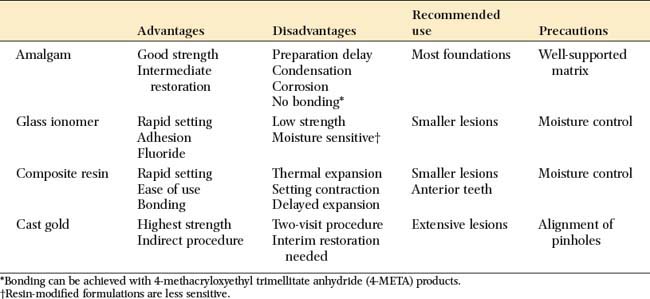

Selection Criteria

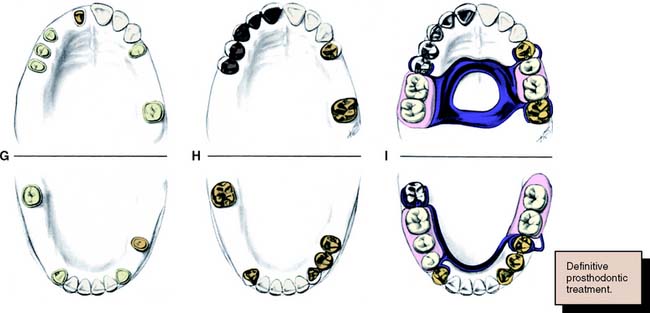

Selection of the foundation material depends on the extent of tooth destruction, the overall treatment plan, and the operator’s preference (Fig. 6-6). The effect of subsequent tooth preparation for the cast restoration on the retention and resistance of the foundation should be considered. Retention features such as grooves or pinholes should be placed sufficiently pulpally to allow adequate room for the definitive restoration. Adhesive retention may be helpful in preventing loss of the foundation during tooth preparation.

Fig. 6-6 The placement of a foundation restoration depends on the extent of damage to the tooth and should always be designed with the definitive restoration in mind. A, Cement. This is suitable when damage is minimal. B, Amalgam. C, Pin-retained amalgam. D, Cast gold. E, Post and core. (See Chapter 12.)

Dental amalgam

Despite its limitations, amalgam is still the material of choice for most foundation restorations on posterior teeth. It has good resistance to microleakage and is therefore recommended when the crown preparation will not extend more than 1 mm beyond the foundation-tooth junction.4 It can be shaped to ideal restoration form and serves well as an interim restoration. It has better strength than the glass ionomers, and retention can be provided by undercuts, pins, or slots. Adhesive bonding systems such as those based on 4-methacryloxyethyl trimellitate anhydride (4-META) are also available5–8 and may reduce leakage of the restoration.9,10 Additional retention may be provided with the use of polymeric beads supplied with the Amalgambond system.11 Amalgam requires an absolutely rigid matrix for proper condensation; otherwise the foundation will break. Matrix placement can be demanding when a tooth with little remaining coronal tissue is restored. This is discussed in the step-by-step procedure on p. 140. Amalgam has a longer setting time than do the other foundation materials. This normally delays crown preparation until a subsequent patient visit. When this presents a problem, a rapid-setting, high-copper, spherical alloy should be chosen. These can be prepared for a crown about 30 minutes after placement. Spherical amalgams are advantageous for foundation restorations because they have greater early strength than do admixed materials, which makes fracture soon after placement less of a possibility.12

Resin-modified glass ionomer cement

This is a suitable choice for a small lesion. The material sets rapidly, enabling crown preparation to be performed with limited delay. When placed correctly, it exhibits adhesion to dentin, although conventional undercut retention is needed to supplement this. It is important to select a material that has adequate radiopacity. A formulation that is more radiolucent than dentin should not be used as a core, because its radiographic appearance may suggest recurrent caries.13 The presence of fluoride in resin modified glass ionomers may help prevent recurrent caries. The chief disadvantage of glass ionomers is their comparatively low strength, which may make the material inferior to amalgam or composite resin for the longer term restoration of extensive lesions.14,15

Composite resin

Composite resin exhibits many of the advantages of glass ionomers. It does not require condensation and sets rapidly. Formulations are available that release fluoride, which may provide an anticariogenic benefit.16 Bonding is achieved with a dentinal bonding agent or by etching a glass ionomer liner. Neither method develops the bond strengths needed to withstand high masticatory forces, and conventional undercut retention is also needed. There are concerns about continued polymerization of the resin and its high thermal expansion coefficient, which may lead to microleakage of the crown.17 Also of concern is the moisture sorption properties of composite resin that causes delayed expansion and may lead to axial binding of crowns made on composite resin cores.18,19 Delayed expansion is not a problem with traditional glass ionomer,20 but it is a problem with the resin–modified glass ionomers and the compomer materials.19 Conventional tooth-colored composite resin is not recommended as a foundation material, because it is difficult to discern the composite-tooth junction. Special colored core materials should be used.

Step-by-Step Procedures

Amalgam core

Retention can also be provided by slots or wells. These create less residual stress in the dentin and thus reduces the risk of pulp exposure or damage.22–26 They should be placed pulpally to the intended crown margin, at a depth of about 1 mm, with a small carbide bur. Careful condensation of amalgam into the slots ensures good restoration retention.

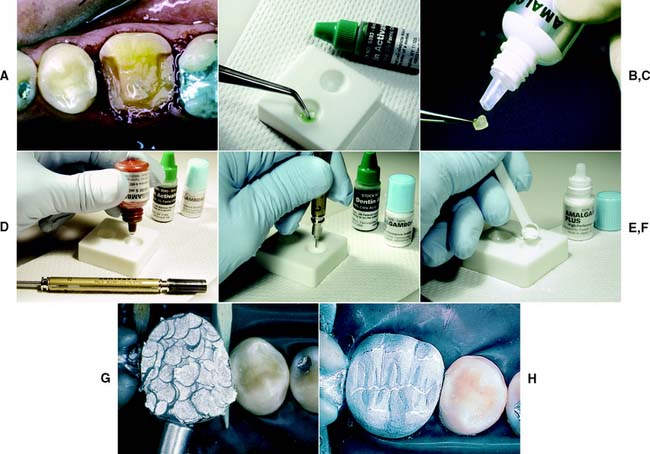

Bonding agents can assist amalgam retention, but adhesion is not adequate to resist occlusal loading. Retention is currently best provided by conventional means. An example of the use of bonding agents appears in Figure 6-8. If bonding agents are used, the clinician should follow the manufacturer’s directions about storage and manipulation.

Matrix placement

A rigid, well-contoured matrix allows the amalgam to be properly condensed and facilitates carving. However, it can present a problem when much tooth structure is missing. Conventional matrix retainers, such as the Tofflemire, are unstable if both the lingual and the buccal walls are missing. A circumferential matrix (e.g., the AutoMatrix Retainerless Matrix System*) is useful for extensive restorations. Alternatives include copper bands or orthodontic bands. These are removed by cutting with a bur after the amalgam has set. Stability of the matrix is improved by proximal wedging, by crimping to shape, and by using modeling plastic or autopolymerizing acrylic resin for external stabilization27,28 (Fig. 6-9).

Contouring and finishing

Care is needed to prevent amalgam fracture during matrix removal. After allowing time for setting, the dentist trims the amalgam away from the occlusal edge of the matrix and removes the wedges and matrix retainer. At this stage, it is helpful to cut the buccal ends of the matrix band with scissors close to the tooth. Then the band can be pulled through the proximal contacts toward the lingual aspect. Pulling the band occlusally is more likely to fracture the freshly placed amalgam.

Glass ionomer core

Composite resin

Composite resin foundations are much stronger than glass ionomer foundations, a difference that correlates with the higher diametral tensile strength of the composite.30 They are strong enough for larger pin-retained cores. However, the current materials have disadvantages, particularly their absorption of moisture and high thermal expansion, which has led many dentists to avoid composite resin foundations entirely.

Preparation

Because the material sets rapidly (about 5 minutes), composite resin is generally chosen if the dentist wishes to place the foundation and prepare the tooth during the same visit. The crown is prepared to approximate shape first, and then existing restorations and caries are removed. A glass ionomer is an appropriate choice of liner, with additional retention being provided by pins. For convenient access, the pinholes can be prepared and the liner placed before the pins are seated.

Placement

Both light-cured and chemically cured core composite materials are available. Light-cured composite materials have the convenience of extended working time, but there is concern about the adequacy of polymerization, especially around the pins.31 The autopolymerizing materials need to be mixed and placed quickly, preferably with the aid of a composite syringe (C-R® syringes).* A Mylar matrix is used to confine them and provide good adaptation.

Pin-retained cast core (Fig. 6-11)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses