Chapter 6

Heart Failure (or Congestive Heart Failure)

Heart failure (HF) is primarily a condition of the elderly and as such it is a major and growing public health problem in the United States.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

HF, often called congestive heart failure (CHF), is not an actual diagnosis; rather, it manifests as a symptom complex that can be the result of any of a number of specific diseases (

Box 6-1 Most Common Causes of Heart Failure

Patients with untreated or poorly managed HF are at high risk during dental treatment for complications such as cardiac arrest, stroke (cerebrovascular accident), and MI. On encountering such a patient, the dentist must be able to recognize the problem from the history and clinical findings; then the patient can be referred for medical diagnosis and management, and the patient’s physician consulted to develop a safe and effective dental management plan.

General Description

Incidence and Prevalence

The prevalence of HF is significantly increasing, primarily as a result of advances in medical technology in preserving and maintaining life after cardiovascular events. Approximately 6 million people in the United States have HF, with more than 550,000 new patients diagnosed each year.

HF is the most common Medicare diagnosis-related group (i.e., hospital discharge diagnosis), and more Medicare dollars are spent for the diagnosis and treatment of HF than for any other clinical entity.

The HF syndrome is characterized by signs and symptoms of intravascular and interstitial volume overload and/or manifestations of inadequate tissue perfusion (

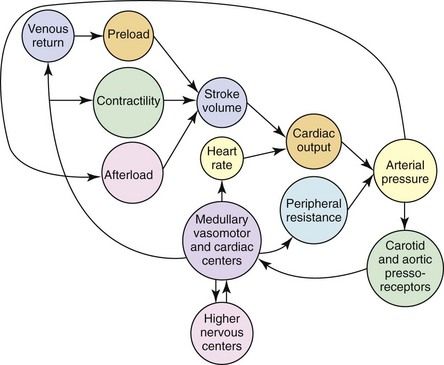

FIGURE 6-2 How stroke volume is produced by the intact circulations of preload, contractility, and afterload. Cardiac output is established by combining stroke volume with heart rate. When this is merged with peripheral vascular resistance, the arterial pressure for tissue perfusion is established. The arterial system’s characteristics contribute to afterload. An increase in afterload lessens stroke volume. When carotid and aortic arch baroreceptors interact with these components, a feedback mechanism is provided to the higher medullary and vasomotor cardiac centers as well as to higher levels in the central nervous system. This results in a modulation influence on heart rate, peripheral vascular resistance, venous return and contractility.

Conditions that cause myocardial necrosis damage and/or produce chronic pressure or volume overload on the heart can induce myocardial dysfunction and HF.

Although the mortality rates for MI and stroke are declining, HF continues to be a major contributor to morbidity and mortality. In the past 20 years, the number of HF hospitalizations increased more than 165%.

Pathophysiology and Complications

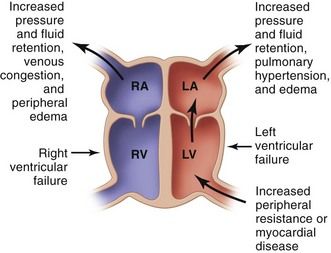

Heart failure is caused by the inability of the heart to function efficiently as a pump, which results in either an inadequate emptying of the ventricles during systole or an incomplete filling of the ventricles during diastole. This in turn results in a decrease in cardiac output, with consequent delivery of an inadequate volume of blood to the tissues, or in a backup of blood, causing systemic congestion. HF may involve one or both ventricles. Most of the acquired disorders that lead to HF result in initial failure of the left ventricle. Left ventricular heart failure (LVHF) often is followed by failure of the right ventricle. In adults, left ventricular involvement is almost always present even if the clinical manifestations are primarily those of right ventricular dysfunction (fluid retention without dyspnea or rales). HF may result from an acute insult to cardiac function, such as with a large MI, or, more commonly, from a chronic process.

HF can result from an acute injury to the heart such as with MI or, more commonly, from a chronic process such as that associated with hypertension or cardiomyopathy. Failure of the heart most often begins with LVHF brought on by an increased workload or disease of the heart muscle.

The most common cause of right-sided heart failure is preceding failure of the left ventricle.

Ventricular failure leads to dilation and hypertrophy of the ventricle as it attempts to compensate for its inability to keep up with the workload. Venous pressure and myocardial tone increase along with the increase in blood volume. The net effect is diastolic dilation, which serves to increase the force and volume of the subsequent systolic contraction. These changes lead to dyspnea, orthopnea, and pulmonary edema. When right-sided ventricular enlargement occurs as a result of a lung disorder (e.g., emphysema) that produces pulmonary hypertension, the condition is called cor pulmonale.

Signs and symptoms of HF appear when the heart no longer functions properly as a pump. As the cardiac output falls, an increasing disproportion is observed between the required hemodynamic load and the capacity of the heart to handle the load. With decreasing cardiac output, stimulation of the renin-angiotensin system and the sympathetic nervous system (i.e., neurohumoral responses) occurs in an attempt to compensate for the loss of function.

The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) classification of HF consists of four stages, reflecting the fact that HF is a progressive disease for which the outcome can be modified by early identification and treatment.

The difference between stage A and stage B is that in stage A, patients do not demonstrate left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) or dysfunction, whereas in stage B, LVH and/or dysfunction (structural heart disease) is present. Stage C is the disease designation for patients with past or present symptoms of HF associated with underlying structural heart disease (the bulk of patients), and stage D, for patients with refractory HF who might be eligible for specialized, advanced treatment or for end-of-life care. This classification system complements the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification system, which is discussed in the next section (“Signs and Symptoms”).

HF is a progressive disease, and symptoms will worsen over time owing to the ongoing deterioration of cardiac structure and function. The prognosis is better if the underlying cause can be treated. At 1 year after the diagnosis of HF, 20% of patients will succumb to the disease. In people diagnosed with HF, sudden death occurs at a rate six to nine times that for the general population.

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

The symptoms and signs of HF (

Box 6-2 Symptoms of Heart Failure

Dyspnea (perceived shortness of breath)

Orthopnea (dyspnea experienced with patient in recumbent position)

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (dyspnea awakening patient from sleep)

Acute pulmonary edema (cough or progressive dyspnea)

Exercise intolerance (inablility to climb a flight of stairs)

Dependent edema (swelling of feet and ankles after standing or walking)

Report of weight gain or increased abdominal girth (fluid accumulation; ascites)

Right upper quadrant pain (liver congestion)

Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, constipation (bowel edema)

Hyperventilation followed by apnea during sleep (Cheyne-Stokes respiration)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses