Chapter 6

Anatomical Variations

Surgical procedures designed to alter the form of the jaws or their function require the existing structures to be quantified in light of aesthetic and functional needs. Sufficient quantity of bone of adequate quality is required to provide appropriate support to withstand functional and parafunctional loads. Additionally, the position of the bone should be such that it allows implants to be placed in positions permitting normal function with the opposing jaw.

This should enable the prosthesis to be constructed in a manner that ensures that the aesthetic needs are met both in terms of the facial form and the emergence profile; this, in turn, will enhance the ability of the patient to carry out good oral hygiene.

Atrophy

Pathology, dysfunction or disuse atrophy may result in deficient ridges. These have been classified by numerous authors based on observation and quantification or treatment possibilities.48–52 The aim of this section is not to elaborate on these but to focus on variations resulting from the different locations within the mouth.

Bone Quality

Bone quality has been described by a number of authors. Lekholm et al.51 divided bone density into four classes based on the proportions of cortical and cancellous bone. Misch described the four qualities of bone according to their resistance to drilling.53,54

The clinical distinction between the two middle grades of bone in both these systems is often difficult to make and is of doubtful significance in clinical practice. A number of authors have addressed this issue and based their conclusions both on clinical and radiological observations.

Clinical perception of bone density is considered to be most accurately made using hand instruments.55 Clinical classification of the bone density was compared with histomorphometric analysis, and no significant differences could be found between the two middle classifications in the above systems.55 Analysis of bone density using modern imaging techniques (interactive CT) also showed the two middle grades to be difficult to differentiate.39

Other clinicians have adjusted their clinical approach based on the quality of bone. Nentwig has a specific protocol that relates to the surgical and prosthodontic management of three different bone qualities: hard, medium and soft. His assessment of bone quality is made clinically and ultimately by the type of hand instrument required to complete the osteotomy and bone tapping.9

The density of bone encountered is used to moderate the manner in which the implants are brought into function, based on the concept of progressive loading as introduced by Misch.53,54

Anterior Maxilla

The factors significant to the anterior maxilla are outlined below.

Bone Quantity

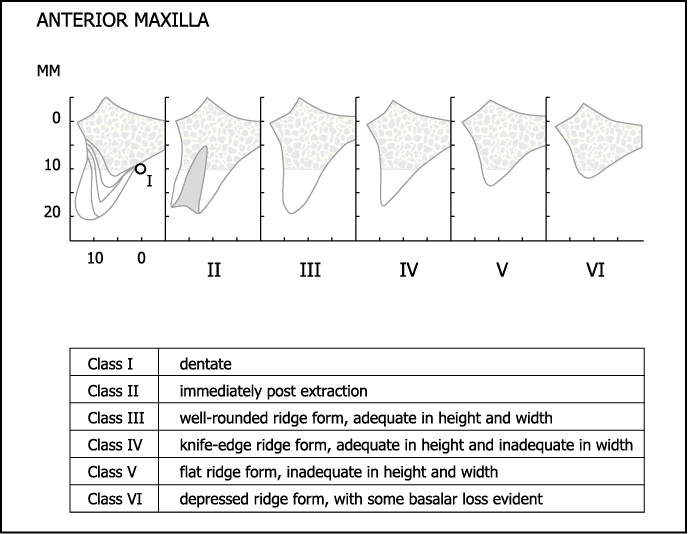

Following tooth loss, a reduction in ridge width takes place, which will vary from person to person, depending on numerous factors. Typically, the reduction takes place at the expense of the labial bone. A reduction in height is also observed. Within the first year of tooth loss, approximately 3 to 4 mm of height is lost where adjacent teeth are not present to sustain bone height.56 This, of course, has a significant effect on the aesthetic outcome in patients who have a high smile-line. The resorption pattern of the anterior maxilla is depicted in Fig 6-1.

Fig 6-1 Cawood and Howell classification for the anterior maxilla.50 Class IV is the form of ridge that is most commonly found. It often has separate cortical plates with intervening cancellous bone (IVa), but on occasion the two cortical plates may be fused (IVb).

Bone Quality

The alveolar ridge in the anterior maxilla most commonly consists of a thin and malleable cortical plate on the labial aspect and a dense and thicker cortical plate on the palatal aspect. There is often intervening cancellous bone of varying density (Cawood and Howell classification IVa). The quality of bone most prevalent in the anterior maxilla is of medium density, lying between the dense cortical bone of the anterior mandible and the sparsely trabeculated cancellous bone of the posterior maxilla.

Ridge Orientation

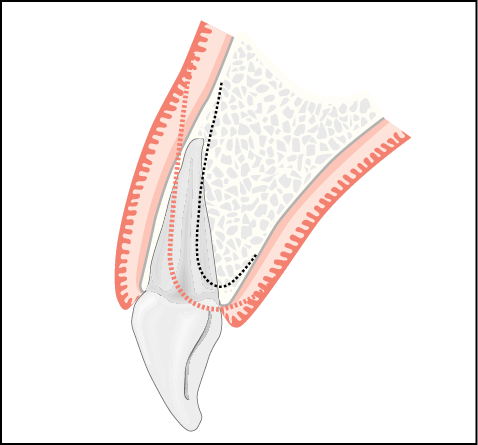

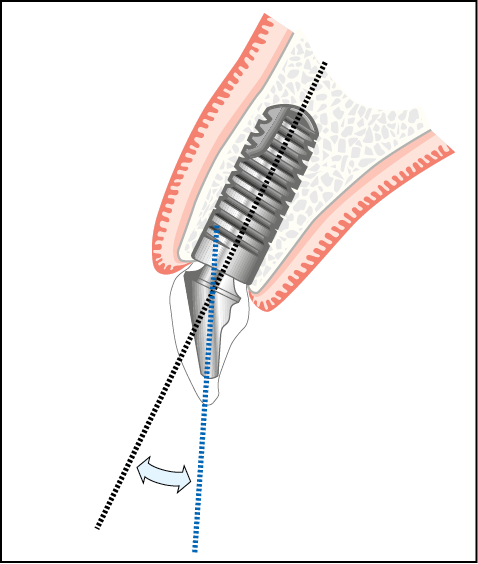

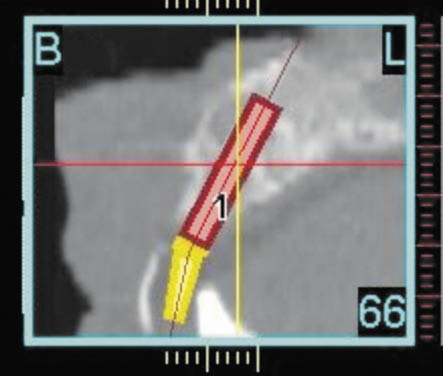

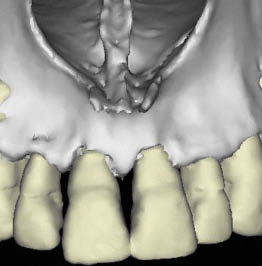

The maxillary ridge typically flares labially, with its crest describing a larger circumference than its base (Fig 6-2). This is of significance in the placement of implants, which must be positioned at an angle to the longitudinal axis of the proposed restoration in keeping with the sound surgical principles of positioning the implants between the cortical plates. As a result, the coronal portion becomes labially inclined and frequently requires angular correction, with the abutment lingually inclined in relation to the implant (Figs 6-3–6-5).

Fig 6-2 Labial view of a dentate skull showing proclination of teeth and flare of maxilla. Note the thin cortical bone overlying the roots of the teeth, which is likely to resorb following tooth loss.

Fig 6-3 Cross-sectional diagram of maxillary incisor showing thin cortical labial socket, with the possible resorption pattern outlined.

Fig 6-4 Implant placed between cortical plates following ridge remodelling, depicting a difference in the angles between the implant and the long axis of crown.

Fig 6-5 CT scan showing angulation between the abutment determined by the future tooth position and the planned implant positioned ideally within the available bone. The labial aspect of the proposed restoration is identified by the radiopaque marker. The palatal aspect of the prosthetic envelope is identified by the position of the mandibular incisor.

Special Clinical Considerations

Aesthetics are of utmost importance, particularly in patients with high smile-lines. The emergence profile, gingival margin and interdental papilla become disproportionately important.

Adequate assessment of the type of gingival–alveolar complex becomes quite important. Patients with thick alveolar ridges, where the roots are not palpable and not prominent, are less difficult to treat. This is because the collapse of the labial plate is less likely following tooth loss. It is often associated with flat, thick gingival margins (Fig 6-6).

Fig 6-6 Patient with flat gingival margins and low papillary height.

This is in contrast with those patients who have prominent roots that are palpable and protrude from interdental depressions. The cortical plate surrounding the vestibular aspect of the roots is thin or non-existent and resorbs rapidly to the level of the interdental bone once the supporting tooth is lost. These patients are more difficult to treat because some form of re-contouring is often required. Caution should also be exercised if immediate implants are being considered because of the risk of resorption. Scalloping of the gingival margin is associated with this type of patient with prominent roots and is indicative of high interdental levels of bone and recession of the vestibular bone (Fig 6-7; see also Fig 6-2).

Fig 6-7 Patient with scalloped gingival margins and significant papillary height.

Support of the upper lip is also a consideration where multiple tooth replacement is necessary. The position of the naso-palatine canal becomes significant when replacing central incisors. It is in this area that bone expansion is most commonly carried out, to enable implants to be placed in the narrow ridges resulting from labial bone loss and to re-contour the labial plate to re-establish an aesthetic ridge form for the emergence profile. Autogenous onlay bone grafts are commonly used, with aesthetics being the primary indication even in situations where adequate bone is present for functional support. CT scans provide an opportunity to examine the underlying morphology and assist in making clinical decisions regarding possible future remodelling of bone (Figs 6-8–6-13).

Fig 6-8 Three-dimensional reconstruction of a CT scan showing minimal scalloping of labial bone. It is possible that less remodelling will be noted in this case.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses