The Periodontal Flap

Classification of Flaps

Periodontal flaps can be classified on the basis of the following:

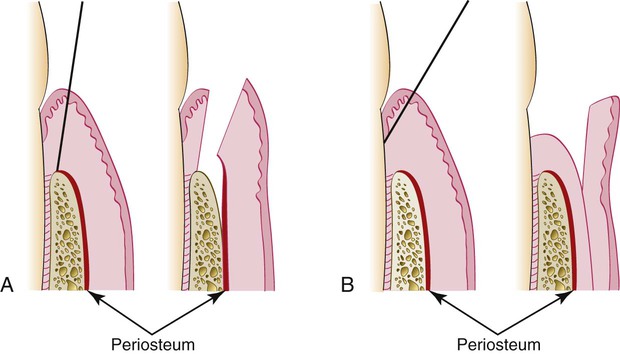

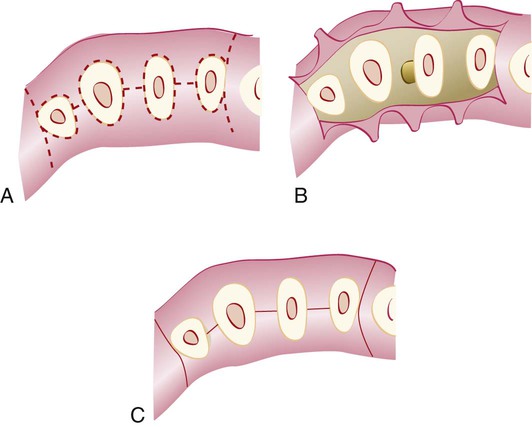

For bone exposure after reflection, the flaps are classified as either full-thickness (mucoperiosteal) or partial-thickness (mucosal) flaps (Figure 57-1).

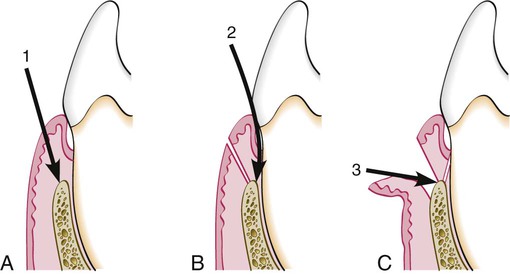

Conflicting data surround the advisability of uncovering the bone when this is not actually needed. When bone is stripped of its periosteum, a loss of marginal bone occurs, and this loss is prevented when the periosteum is left on the bone.4 Although this is usually not clinically significant,7 the differences may be significant in some cases (Figure 57-2). The partial-thickness flap may be necessary when the crestal bone margin is thin and exposed with an apically placed flap or when dehiscences or fenestrations are present. The periosteum left on the bone may also be used for suturing the flap when it is displaced apically.

Conventional flaps include the modified Widman flap, the undisplaced flap, the apically displaced flap, and the flap for reconstructive procedures. These techniques are described in detail in Chapter 59.

Flap Design

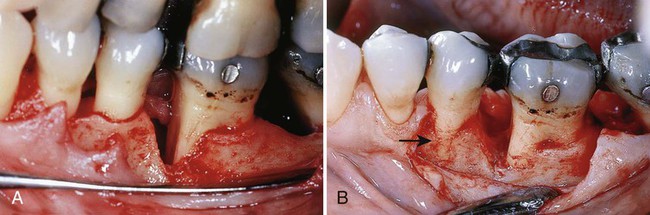

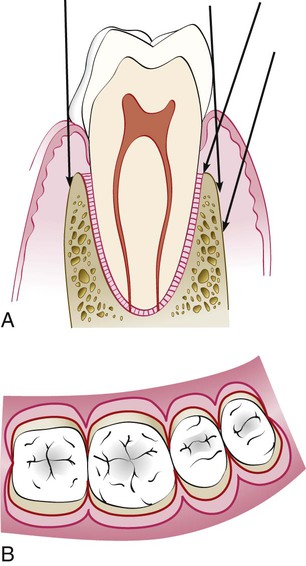

For the conventional flap procedure, the incisions for the facial and the lingual or palatal flap reach the tip of the interdental papilla or its vicinity, thereby splitting the papilla into a facial half and a lingual or palatal half (Figures 57-3 and 57-4).

Incisions

Horizontal Incisions

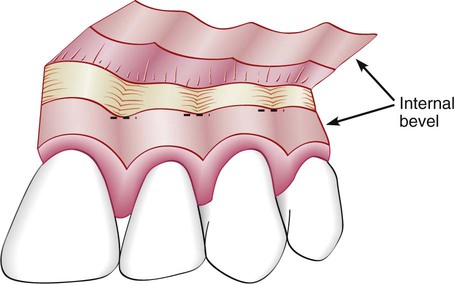

Horizontal incisions are directed along the margin of the gingiva in a mesial or distal direction. Two types of horizontal incisions have been recommended: the internal bevel incision,6 which starts at a distance from the gingival margin and which is aimed at the bone crest, and the crevicular incision, which starts at the bottom of the pocket and which is directed to the bone margin. In addition, the interdental incision is performed after the flap is elevated to remove the interdental tissue.

The internal bevel incision is basic to most periodontal flap procedures. It is the incision from which the flap is reflected to expose the underlying bone and root. The internal bevel incision accomplishes three important objectives: (1) it removes the pocket lining; (2) it conserves the relatively uninvolved outer surface of the gingiva, which, if apically positioned, becomes attached gingiva; and (3) it produces a sharp, thin flap margin for adaptation to the bone–tooth junction. This incision has also been termed the first incision, because it is the initial incision for the reflection of a periodontal flap; it has also been called the reverse bevel incision, because its bevel is in reverse direction from that of the gingivectomy incision. The no. 15 or 15C surgical blade is used most often to make this incision. That portion of the gingiva left around the tooth contains the epithelium of the pocket lining and the adjacent granulomatous tissue. It is discarded after the crevicular (second) and interdental (third) incisions are performed (Figure 57-5).

The internal bevel incision starts from a designated area on the gingiva, and it is then directed to an area at or near the crest of the bone (Figure 57-6). The starting point on the gingiva is determined by whether the flap is apically displaced or not displaced (Figure 57-7).

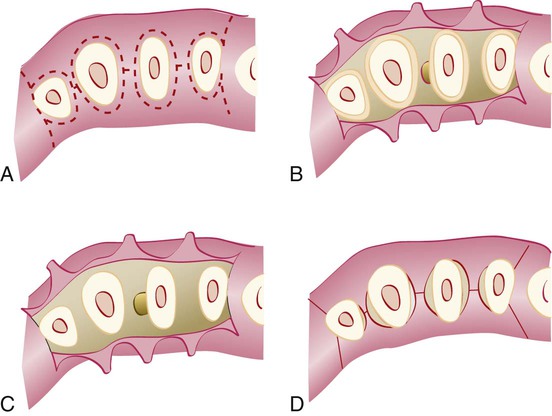

The crevicular incision, which is also called the second incision, is made from the base of the pocket to the crest of the bone (Figure 57-8). This incision, together with the initial reverse bevel incision, forms a V-shaped wedge that ends at or near the crest of bone. This wedge of tissue contains most of the inflamed and granulomatous areas that constitute the lateral wall of the pocket as well as the junctional epithelium and the connective tissue fibers that still persist between the bottom of the pocket and the crest of the bone. The incision is carried around the entire tooth. The beak-shaped no. 12D blade is usually used for this incision.

A periosteal elevator is inserted into the initial internal bevel incision, and the flap is separated from the bone. The most apical end of the internal bevel incision is exposed and visible. With this access, the surgeon is able to make the third incision, which is also known as the interdental incision, to separate the collar of gingiva that is left around the tooth. The Orban knife is usually used for this incision. The incision is made not only around the facial and lingual radicular area but also interdentally, where it connects the facial and lingual segments to free the gingiva completely around the tooth (Figure 57-9; see Figure 57-5).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses