Chapter 5

Problem Solving in the Diagnosis of Treatment Failure

“In attempting to assign the success or failure of operations upon diseased teeth to their proper causes, factors of the greatest importance are frequently left out of account, and the results ascribed to some agent which may have been entirely indifferent. One of these factors, which forms the very foundation of successful root-treatment, is the manner in which the mechanical cleansing of the canal is carried out.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

The patient’s subjective data and objective clinical findings to confirm a pulpal diagnosis are discussed in

Nonsurgical Treatment Success

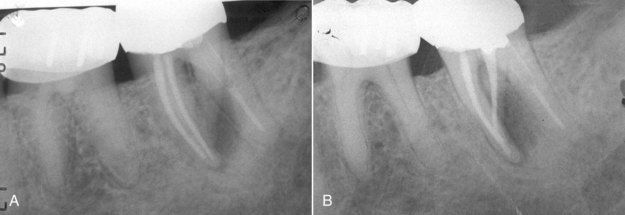

A simplified definition of favorable outcomes with nonsurgical treatment procedures might be: If there is no radiographic evidence of periradicular pathosis prior to root canal treatment, no radiographic signs of pathosis should ever appear following treatment (

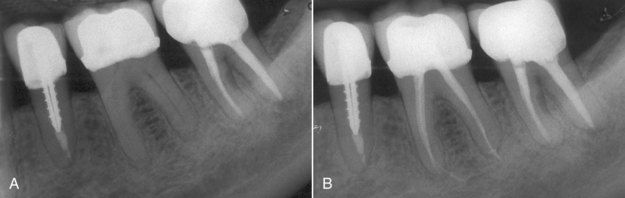

FIGURE 5-1 A, Routine endodontic case without radiographic evidence of periapical pathosis at the time of treatment in February 1978. B, Reevaluation June 2006. The tooth is asymptomatic with normal function.

FIGURE 5-2 A, Large periapical lesion secondary to necrotic pulp on a mandibular right first molar. Lesion appears to have a periodontal complication, but clinical probings were normal. There was a draining sinus tract on the edentulous ridge distal to the tooth. B, One-year posttreatment reexamination. The apical and distal bone is completely restored along with a periodontal ligament space of uniform and normal width.

With these concepts for success in mind, a clinical diagnostic case involving a mixed dentition of root-treated treated and untreated teeth would require a separate and distinct evaluation of the treated teeth, as opposed to just dismissing them as not being the cause of the patient’s symptoms.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

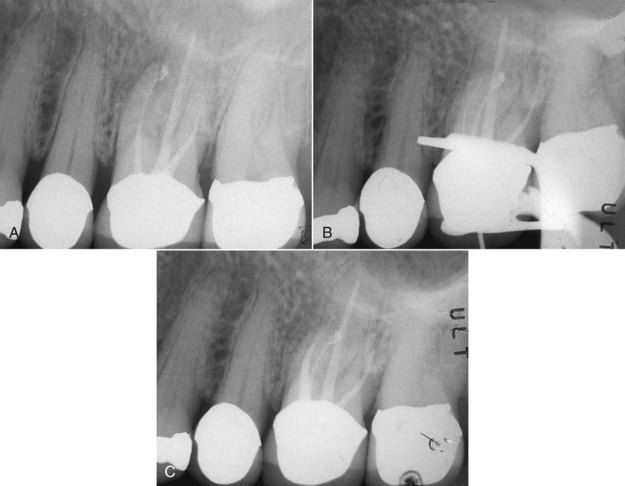

A 46-year-old patient complained of a periodic dull pain in the lower right quadrant. There was discomfort on chewing but no history of thermal sensitivity. The radiograph indicated previous root canal treatment of the mandibular second premolar and second molar, which according to the patient was completed 7 to 10 years previously (

FIGURE 5-3 A, Mandibular left posterior dentition in which patient is experiencing pain. Note questionable radiographic appearance of apical periodontal ligament space on distal root of second molar. B, Post treatment of first molar, which clinical examination identified as the cause of symptoms. The two adjacent teeth were judged to have successful root canal treatment.

Solution

The challenge was to arrive at the correct diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included bruxism, possible recurrent periapical pathosis on either of the treated teeth, or pulpal disease in the first molar. Occlusion was evaluated, and no occlusal prematurities were found that would account for the percussion tenderness on the first molar. Thermal sensibility tests on the first molar failed to elicit a response. The diagnosis of pulpal necrosis of the first molar was made; root canal treatment of the other two teeth was judged to be successful. The completed root canal treatment of the first molar is seen in

Incomplete Nonsurgical Treatment

Occasionally the cause of periapical pathosis on a multicanal pulpless tooth can easily be identified when it is obvious that one of the canals has no root filling. It is a matter of semantics whether or not to label this condition as a treatment failure, since the canal in question was never treated. At the same time, it is clearly a failure on the part of the clinician to locate and treat all canals present in the tooth.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

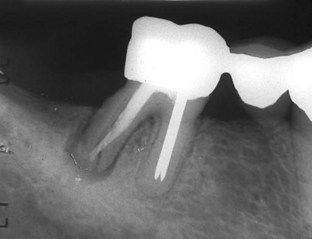

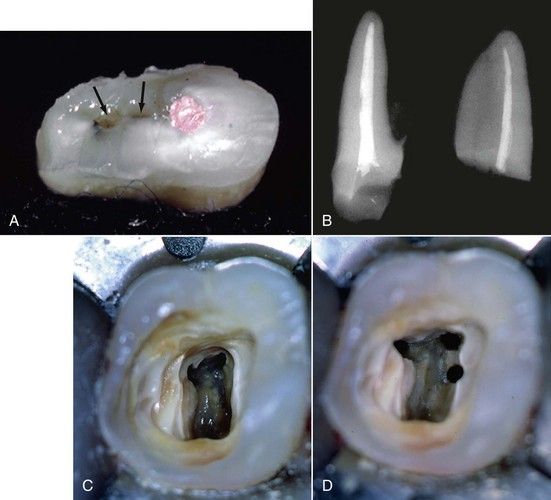

The patient was a 55-year-old female with an acute apical abscess. She gave a history that the maxillary left first molar had root canal treatment approximately 3 years previously (

Solution

What was the differential diagnostic parameter? The root canal filling material in both buccal roots suggested that the canals were adequately but not ideally cleaned and shaped, and therefore a true failure was a possibility. A more likely diagnosis for this root was the presence of a second canal or irregular canal configuration.

FIGURE 5-5 A, Cross-section of typical mesial buccal root, indicating a treated mesial buccal canal and an untreated second mesial buccal canal connected by an isthmus (arrows). B, Radiographic view palatal root (left) and lateral view buccal root (right) of same tooth. C, Pulp chamber with identification of mesial buccal, distal buccal, and palatal canals. D, Identification of the second mesial buccal canal.

FIGURE 5-6 A, Inadequate root canal treatment of a maxillary left first molar in which there is also an untreated second mesial buccal root. Clinically, there was local swelling and palpation tenderness localized to the area over the apex of the mesial buccal root. B, Completed revision. Note treatment of second mesial buccal root.

One of the more perplexing clinical circumstances with the maxillary first molar (and any other tooth that may have a second canal located in the buccal-lingual dimension) is when there is no radiolucency seen on the radiograph, or when the presence of a radiolucency is questionable no matter what angle the film is exposed. In these cases, there may be a lesion present directly behind the root, which is blocked from view by the widening of the mesial buccal root as it approaches the cervical portion of the tooth. An example would be the mesial buccal root of a maxillary first molar with a small palatally located second canal orifice well below the mesial buccal apex. Clinically, the only finding may be tenderness to percussion that is different on the mesial buccal root than on the other roots. Some cases may exhibit localized tenderness to palpation over the root as well. In these cases, it is reasonable to consider either nonsurgical or surgical revision of this root, the choice depending on the other circumstances surrounding the case.

A second common way in which infected/inflamed pulpal tissue in untreated canals causes a symptomatic clinical problem is the onset of acute thermal sensitivity.

In the evaluation of recurrent pathosis on root-treated teeth, it is important to consider an untreated canal in any tooth that anatomically could have one. These generally are present in a buccal-lingual dimension, as discussed earlier with the maxillary first molar.

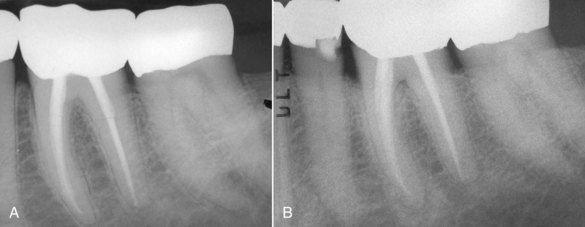

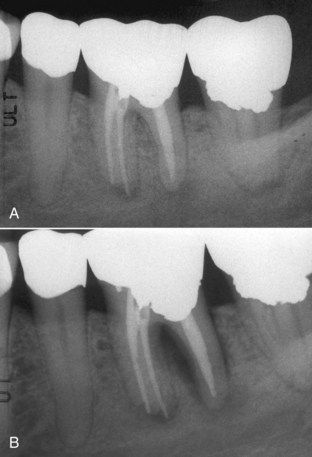

FIGURE 5-7 A, Previously treated mandibular right first molar with an apical lesion on the distal apex. An untreated second canal in the distal root was the suspected etiology. B, Postrevision radiograph indicating treatment of two distal canals.

FIGURE 5-8 A, Mandibular left second molar with a lesion caused by failure to treat a second distal root. The endodontic treatment present in the other three canals was judged to be adequate. B, Post revision radiograph.

FIGURE 5-11 A, Root treated maxillary first premolar with an apical lesion. B, Postrevision radiograph indicating treatment of a third canal that was the cause of continuing pathosis.

(Courtesy Dr. Ryan Wynne.)

A second concept of incomplete root canal treatment may be identified as any treatment falling far below the standard of care with respect to obturation as evaluated on a good periapical radiograph. Cleaning and shaping are undoubtedly included as a cause of failure, but inadequacy of obturation is most obvious upon radiographic examination (

FIGURE 5-12 A, Maxillary central incisor with inadequate root canal treatment. B, Mandibular first molar with inadequate root canal treatment and continuing periapical pathosis.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

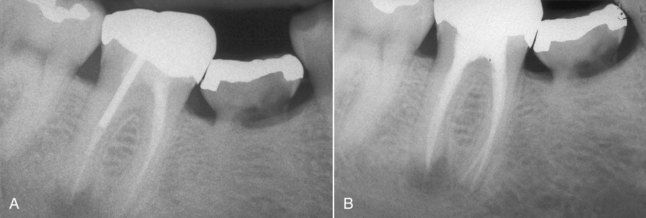

A 42-year-old patient had a maxillary second molar with only one large canal (

Solution

Following removal of the original gutta-percha filling material, copious purulent drainage was observed. The canal was cleaned, and a calcium hydroxide intracanal dressing was placed. Fortunately all symptoms resolved quickly. After 1 month, sulcular probing depths had returned to normal, mobility had disappeared, and there was no drainage from the canal upon reentry. The revision was completed and a 31-month reexamination indicated complete regeneration of bone in the previous periapical radiolucency (see

Alternative Diagnoses Often Confused With Treatment Failure

If the possibility of incomplete root canal treatment has been eliminated from the differential diagnosis, alternative diagnoses should be considered. These entities have clinical and radiographic features that mimic those of root treatment failure but in reality are unrelated. The two categories are lesions associated with root fracture and lesions associated with chronic periodontal pathosis.

FIGURE 5-15 A, Normal probing depth found to the mesial of midlabial. B, Normal probing depth found to the distal of midlabial. C, Probing to the apex in the midlabial position.

It is common to find chronic sinus drainage tracts associated with these lesions; oftentimes two tracts will appear.

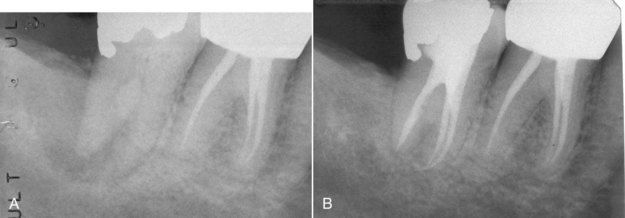

Clinical and radiographic changes that typify vertical fractures often take time. Tenderness to percussion or continuous low-grade pain may begin at the time the fracture occurs, but development of a periodontal defect that can be probed may not occur for weeks or months. Radiographic changes will not occur until there has been a sufficiently wide zone of bone resorption along the fracture line. The patient in

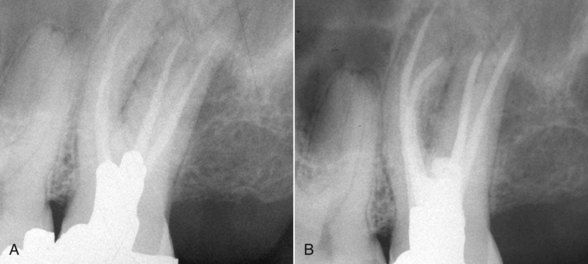

FIGURE 5-17 A, Mandibular left first molar referred with provisional diagnosis of “endodontic failure.” B, One month later, new radiograph displays bone loss consistent with vertical root fracture.

FIGURE 5-18 Maxillary central incisor with apparent apical lesion. Note vertical fracture line visible in apical third. Lesion was found to probe as a sinus tract–type probing in both midlabial and midpalatal positions. This probing pattern is consistent with a complete fracture through the root.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

The patient was a 63-year-old female with a recent history of local swelling and tenderness in buccal gingival tissues in the mandibular right molar area. The tooth was an abutment for a fixed bridge in place for many years. The radiograph indicated that the tooth had had root canal treatment. There was also a widening of the periodontal ligament space around the distal root (

FIGURE 5-19 A, Mandibular second molar with history of recurrent local swelling. Tentative diagnosis was “endodontic failure.” Normal probings were found around mesial half of root. B, Probing to the apex on the buccal of the distal root. C, Probing to the apex on the lingual of the distal root that completes a probing pattern consistent with a vertical fracture extending completely through the distal root from buccal to lingual.

Solution

Periodontal probings were made in 1-mm increments circumferentially around the tooth. A normal sulcus depth of 3 mm was found circumferentially on the mesial half of the tooth. Deep narrow periodontal defects on both the buccal and lingual aspects of the distal root indicated a through and through vertical fracture (see

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses