Development, Form, and Eruption

• To understand how the tooth germs develop within the crypts

• To understand how the growth centers or lobes fuse and form a tooth

• To understand that this fusion can take a variety of forms, which result in different types of teeth such as incisors, premolars, and molars

• To know how many lobes form each type of tooth and where the lobes are located

• To understand the eruption schedule of the deciduous and permanent teeth

• To understand some general rules about the eruption of teeth

• To understand the phenomena of mesial drift, root resorption, and exfoliation

• To understand the implications of the terms impacted teeth, congenitally missing teeth, attrition, occlusal plane, and curve of Spee

• To understand the periods of primary, mixed, and permanent dentition

DEVELOPMENT AND FORM

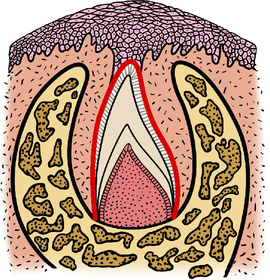

During the sixth week of fetal life (7 or 8 months before birth), tiny tooth buds, sometimes called tooth germs, begin to grow within the alveolar process of the fetus. Tooth germs are small clumps of cells that have the ability to form the tooth tissues (dentin, enamel, cementum, and pulp). Both the primary and secondary teeth develop from these tooth germs, which later are located within cavities of the alveolar process called crypts (see Chapter 19 and Figs. 19-1 to 19-4)

At this time the dentin and enamel begin to form, followed later in development by the cementum. The type of dentin formed at this early stage is called primary dentin, and it occurs before root completion. Secondary dentin is continually formed within the tooth by the same odontoblasts that form regular dentin. This process continues throughout one’s entire lifetime. Secondary dentin differs from reparative dentin in that reparative dentin is laid down locally as protection for the pulp from irritation, caries, or trauma (see Chapter 20).

The earliest evidence of tooth formation occurs during the sixth week of embryonic life. At this time the dental lamina begins to form (see Chapter 19).

The primary teeth begin to calcify by about the fourth or fifth month of fetal life. The process of calcification is the hardening of the tooth tissues by the deposition of mineral salts within these tissues (Fig. 5-1). This process continues until about the third or fourth year after birth, when the deciduous roots become fully formed.

Soon after birth the permanent teeth begin to calcify and continue until about the twenty-fifth year, when the roots of the third molars become calcified. The last area of the tooth to become calcified is the apex of the root (see Chapter 21.)

Developmental Lobes

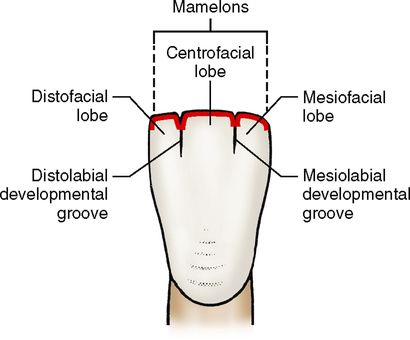

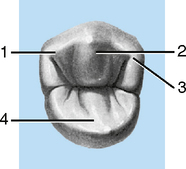

The number of developmental lobes necessary for the formation of a tooth depends on the particular tooth and how many cusps it has. For instance, all the anterior teeth develop from four lobes—three labial and one lingual. The three labial lobes form the labial surface of each tooth. The mamelons, which are evident after the eruption of incisor teeth, are the incisal ridges of these three labial developmental lobes, and they also are separated by developmental grooves (see Fig. 2-22).

In Fig. 5-2 notice how the three labial lobes fuse to form the entire labial surface. The only evidence that three separate lobes existed is at the incisal ridge, where the mamelons are distinct and separate, and on the labial surface of the tooth, where developmental lines or grooves are evident. The three labial developmental lobes are called the mesiofacial, centrofacial, and distofacial lobes. The sole lingual lobe is appropriately called the lingual lobe and makes up the entire cingulum on the lingual surface of the tooth.

Lobes and Cusps

Premolars

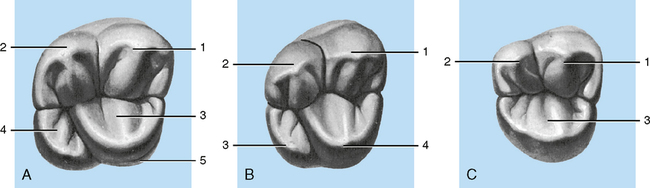

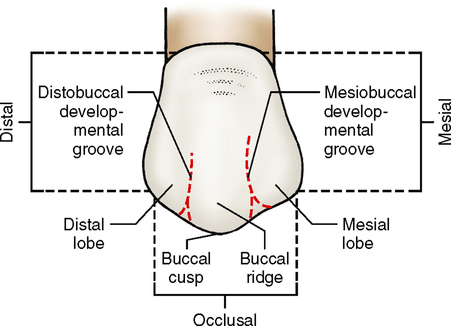

The maxillary premolars are like the anterior teeth in that they have three facial lobes and one lingual lobe. However, unlike the anterior teeth, the three facial lobes of maxillary premolars form one high buccal cusp instead of an incisal ridge, and the single lingual cusp forms a large lingual cusp rather than a cingulum. The names of the lobes are the same as those for the anterior teeth (Fig. 5-3).

The two-cusp variety of the mandibular second premolar is exactly the same in number and arrangement of lobes as the mandibular first premolar. The lingual cusp of this bicuspid is longer than that of the mandibular first premolar. The facial lobes and cusps of the three-cusp variety of the mandibular second premolar are exactly the same as on the first premolar, but the lingual lobes are quite different. First, two lobes, a mesiolingual and a distolingual lobe, instead of a single lobe, results in two separate lingual cusps, with the mesiolingual cusp usually being larger than the distolingual cusp (Fig. 5-4). A considerable difference is also apparent in the number and location of the developmental grooves, with an additional groove located between the two lingual cusps. Further differences in anatomy are discussed in Chapter 14.

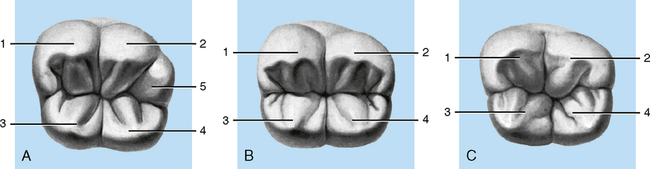

Molars

The maxillary second molar often does not have a cusp of Carabelli; if it is present, it is much smaller in proportion to the other lobes. Second molars are much smaller than first molars in all cusp proportions as a rule, and the distolingual cusp, which is a minor cusp, is often even smaller in proportion. The minor cusp becomes smaller as the location becomes more posterior. Therefore it is not unusual for third molars to have only major cusps and no minor cusps. A maxillary third molar might have only three cusps, with little or no distolingual cusp. Additionally, the crown is usually smaller and the roots shorter than those of second or first molars (Figs. 5-5 and 5-6).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses