4

The Sinonasal Cavity and Airway

Anatomy

Nose is the term generally used to describe the pyramid-shaped external soft tissue projecting ventral to the surface of the face. Nasal fossa, or nasal cavities, refer to the internal nasal airways.

Topographically, the nose is divided into subunits that have practical importance for reconstructive surgeons. The subunits consist of the nasal dorsum, the nasal sidewalls, the nasal tip and columella, the alar lobule, and the supraalar facets. The nasion is the junction of the root of the nose with the forehead. The lower or caudal free margin of the nose is formed by the alar rim, columella, and tip. Bilaterally, the lateral lower margin of the nose has a rounded expansile region referred to as the alar lobule and consists of skin and soft tissue posterior and inferior to the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage. The dorsum of the nose consists of the nasal bones’ dorsal surfaces superiorly and the dorsal border of the quadrangular cartilage attaching to the upper lateral cartilages inferomedially. The junction of the alae with the face is known as the alar-facial junction.

Som and Curtin (2003) describe the journey of inspired air as it enters the nasal cavity in the following manner:

Inspired air traverses the nasal valve. This is a circular area encompassed by the nasal septum, upper lateral cartilage, tip of the inferior turbinate, and floor of the nose. The total area encompassed by this valve provides the most important resistance to air flow in the nasal cavity. Of slightly lesser importance is the angle formed by the meeting of the quadrangular cartilage of the nasal septum and the inferior border of the upper lateral cartilages which is known as the nasal valve angle. Due to its mobile nature, it is a dynamic structure that narrows and widens with the phases of respiration. It is thus a critical factor in determining airflow through the nasal cavity.

The two sides of the nasal cavity are separated by the nasal septum. The septum supports the bony and cartilaginous vault and the tip of the nose. The main components of the nasal septum are the vomer, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, the quadrangular cartilage, the membranous septum, and the columella. The vomer may be bilaminar due to its embryologic origin; the vomer and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone may become pneumatized.

The perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone fuses with the cribriform plate superiorly. The vomer articulates superiorly with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid and the crest of the sphenoid, anteriorly with the quadrangular cartilage, and inferiorly with the palatine bone and nasal crest of the maxilla. The thin groove of the quadrangular cartilage has as “tongue-in-groove” relationship with the vomer. The posterior border of the vomer is free and divides the posterior choanae.

The inferior concha is a separate bone of the skull. The inferior turbinate is larger than the other turbinates. The nasolacrimal duct drains tears into the inferior meatus. The superior and middle conchae are parts of the ethmoid bone. The middle meatus receives drainage from the frontal sinus (via the frontal recess) drains through the middle meatus, or infundibulum to middle meatus, to the nasal cavity to the nasopharynx. The maxillary sinus (via the maxillary ostium) drains through the infundibulum, the middle meatus, the nasal cavity, and, finally, the nasopharynx. The anterior ethmoid air cells drain via the anterior ethmoid ostia into the nasal cavity. In the ethmoid bone, the uncinate process is a curved lamina that projects downward and backward from this part of the labyrinth. It forms a small part of the medial wall of the maxillary sinus and articulates with the ethmoid process of the inferior nasal concha (Figures 4.1–4.10; Tables 4.1 and 4.2).

Normal Anatomy of the Ostiomeatal Complex

See Chapter 3 for additional information.

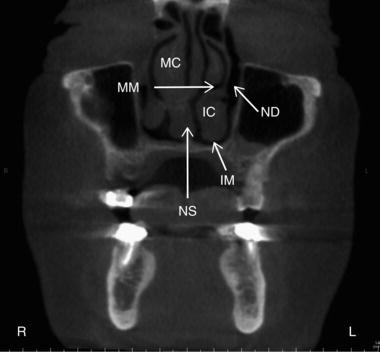

Figure 4.1. Coronal slice at the maxillary first premolar showing the middle concha (MC), middle meatus (MM), nasolacrimal duct (ND), inferior concha (IC), inferior meatus (IM), and nasal septum (NS).

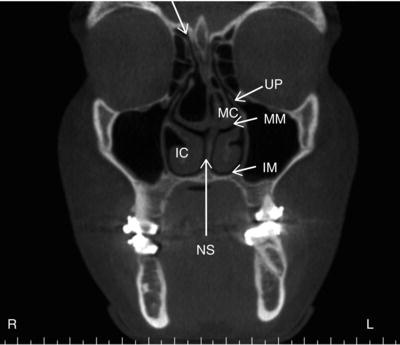

Figure 4.2. Coronal slice at the ostiomeatal unit showing the uncinate process (UP), middle concha (MC), middle meatus (MM), inferior concha (IC), inferior meatus (IM), and nasal septum (NS).

Anatomical Variations of the Nasal Septum

The nasal septum is fundamental to the development of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Deviations of the nasal septum are usually congenital but are due to previous experiences of trauma in some patients. Developmentally, there may be malalignment of the components of the nasal septum (the septal cartilage, perpendicular ethmoid bone, and vomer), which may cause deviation of the nasal septum, deformities of the tongue-in-groove relationship of the cartilage and vomer, or a septal bony spur. About one-third of septal deviations are asymptomatic, however more severe chondrovomer articulation problems may contribute to sinusitis symptoms. Obstruction, secondary inflammation, and infection of the middle meatus have been observed secondary to severe nasal septal deviations (Figures 4.11–4.12).

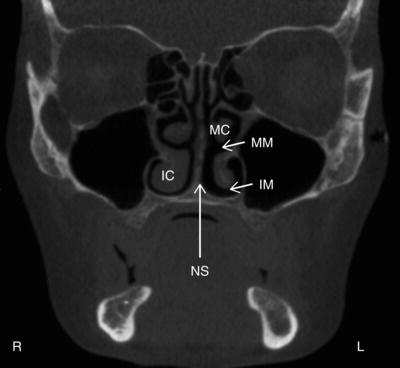

Figure 4.3. Coronal slice at the ostiomeatal unit showing the frontal recess (white arrow), uncinate process (UP), middle concha (MC), middle meatus (MM), inferior concha (IC), inferior meatus (IM), and nasal septum.

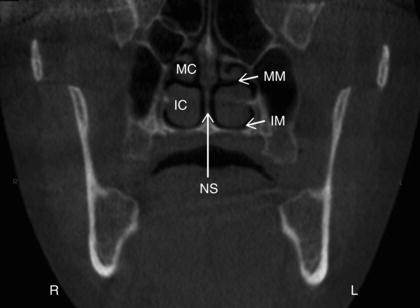

Figure 4.4. Coronal slice at the zygomatic process of the maxilla showing the middle concha (MC), middle meatus (MM), inferior concha (IC), inferior meatus (IM), and nasal septum (NS).

Figure 4.5. Coronal slice at the posterior aspect of the maxillary sinuses showing the middle concha (MC), middle meatus (MM), inferior concha (IC), inferior meatus (IM), and nasal septum (NS).

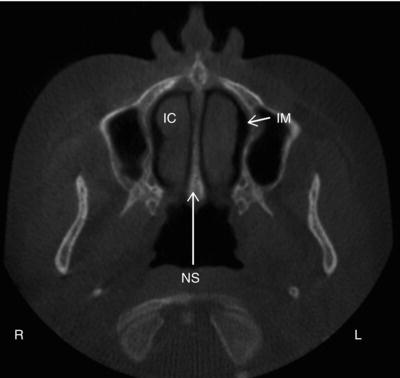

Figure 4.6. Axial slice at the level of the inferior aspect of the maxillary sinuses showing the inferior meatus (IM), inferior concha (IC), and nasal septum (NS).

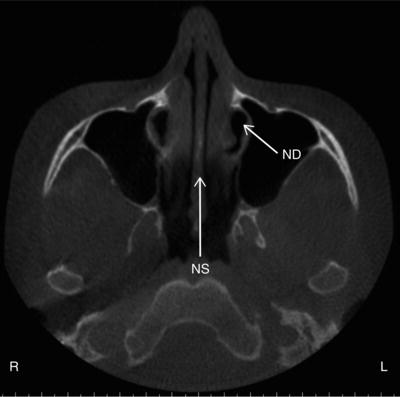

Figure 4.7. Axial slice at the midlevel of the maxillary sinuses showing the nasolacrimal duct (ND) and nasal septum (NS).

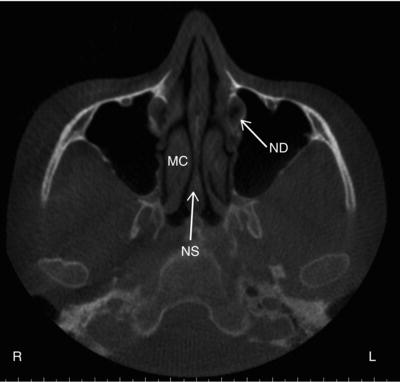

Figure 4.8. Axial slice at the level of the condyles showing the nasolacrimal duct (ND), middle concha (MC), and nasal septum (NS).

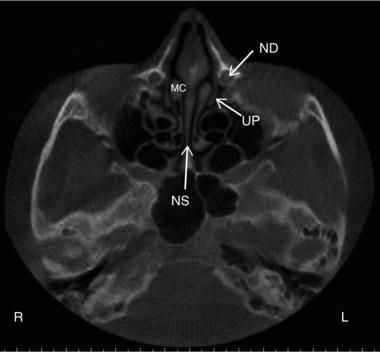

Figure 4.9. Axial slice at the level of the inferior orbits showing the nasolacrimal duct (ND), uncinate process (UP), middle concha (MC), and nasal septum (NS).

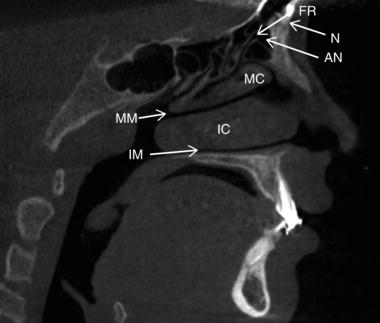

Figure 4.10. Sagittal slice slightly lateral to the midline showing the frontal recess (FR), nasion (N), agger nasi cell (AN), middle concha (MC), middle meatus (MM), inferior concha (IC), and inferior meatus (IM).

Anatomical Variations of the Middle Turbinate

There are several variations of the middle turbinate including paradoxic curvature, concha bullosa, lamellar concha, medial/lateral displacement, L-shaped lateral branding, and sagittal transverse clefts. The first three, which are more common, are described in detail below.

Table 4.1. Anatomical landmarks identifiable on coronal views with corresponding figures.

| Anatomical landmark | Figures visible on |

| Nasolacrimal duct | 4.1 |

| Nasal septum | 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 |

| Inferior meatus | 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 |

| Inferior concha | 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 |

| Middle meatus | 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 |

| Middle concha | 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 |

| Uncinate process | 4.2 |

| Frontal recess | 4.3 |

Table 4.2. Anatomical landmarks identifiable on axial views with corresponding figures.

| Anatomical landmark | Figures visible on |

| Nasolacrimal duct | 4.7 4.8 4.9 |

| Nasal septum | 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 |

| Inferior meatus | 4.6 |

| Inferior concha | 4.6 |

| Middle concha | 4.8 4.9 |

| Uncinate process | 4.9 |

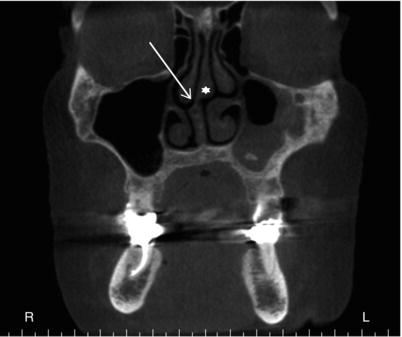

Figure 4.11. Coronal slice showing nasal septum deviated to the right (white arrow) with enlargement of the septal cartilage (septal tubercle) (white star).

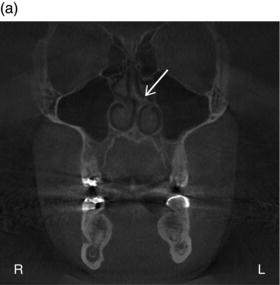

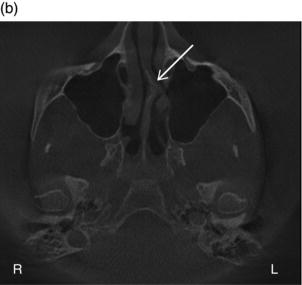

Figure 4.12. (a) Coronal slice showing left-sided bony spur formation at the level of the middle meatus (white arrow); (b) Axial slice showing left-sided bony spur formation (white arrow).

Paradoxic Curvature

Normally the convexity of the middle turbinate is directed laterally, toward the lateral sinus wall. When paradoxically curved, the convexity is directed medially toward the nasal septum. The inferior edge of the middle turbinate may take on excessive curvature, which may then narrow or obstruct the nasal cavity, infundibulum, or middle meatus. Because of the potential narrowing and/or obstruction associated with paradoxic curvature, it is considered a contributing factor to sinusitis by authors Som and Curtin (2003) (Figure 4.13).

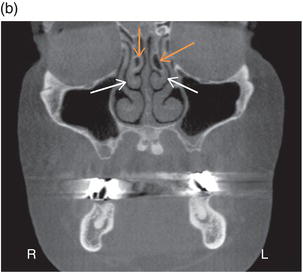

Figure 4.13. (a) Coronal slice showing paradoxical curvature of the left middle concha (white arrow); (b) Coronal slice showing paradoxical curvature of the right and left middle conchae (white arrows) with lamellar concha at the attachment of right and left middle conchae (orange arrows).

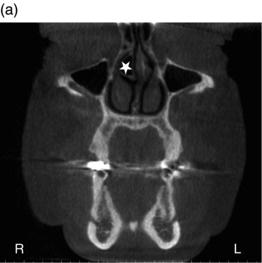

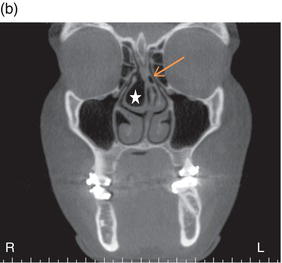

Figure 4.14. (a) Coronal slice showing concha bullosa (aerated concha) of the right middle concha (white star); (b) Coronal slice showing concha bullosa (white star) and lamellar concha (orange arrow).

Concha Bullosa

A concha bullosa is an aerated turbinate; the turbinate most often associated with concha bullosa is the middle turbinate (Figures 4.14–4.16). Concha bullosa may be either unilateral or bilateral; however it is more frequently bilateral in its presentation. Less frequently, aeration of the superior turbinate may occur; an aerated inferior turbinate is uncommon. Classifications of concha bullosae are divided according to degree of turbinate pneumatization. When the pneumatization involves the bulbous segment of the middle turbinate, the term concha bullosa applies. If the pneumatization is limited to the attachment portion of the middle turbinate and does not extend into the bulbous segment, it is called lamellar concha. A concha bullosa of the middle turbinate may cause enlargement of the turbinate such that the middle meatus or infundibulum are obstructed, thus associating concha bullosa with a higher prevalence of ipsilateral sinus disease.

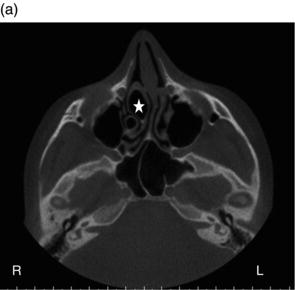

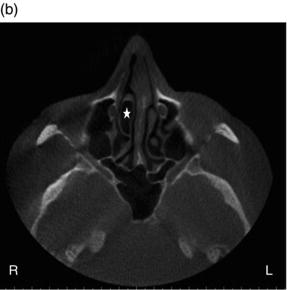

Figure 4.15. Axial slices (a,b) showing concha bullosa (aerated concha) of the right middle concha (white stars).

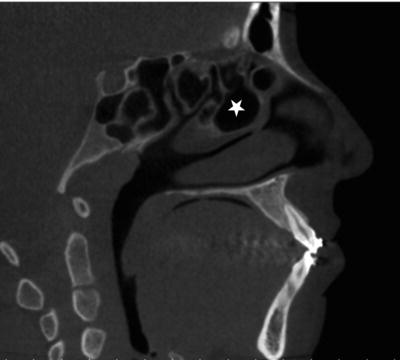

Figure 4.16. Sagittal slice showing concha bullosa (white star).

Lamellar Concha

Only the attachment portion of the middle turbinate is pneumatized, and the pneumatization does not extend into the bulbous segment (see Figures 4.13b, 4.14b, and 4.17).

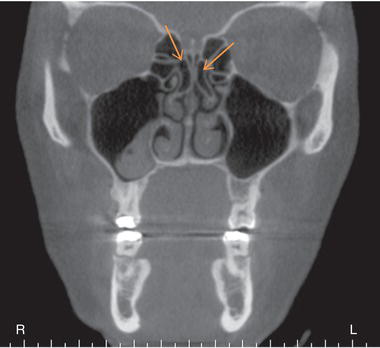

Figure 4.17. Coronal slice showing bilateral lamellar concha (orange arrows).

Anatomy of the Uncinate Process

Attachment

Normally, the upper tip of the uncinate process attaches to the lateral nasal wall where the agger nasi cells are commonly located. Anatomic variations of the uncinate attachment include attachment to the lamina papyracea, the lateral surface of the middle turbinate, or the fovea ethmoidalis in the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. Sometimes the free edge of the uncinate process may adhere to the orbital floor or the inferior aspect of the lamina papyracea, a condition known as an atelectatic uncinate process , and is associated with a hypoplastic, and often opacified, ipsilateral maxillary sinus secondary to closure of the infundibulum. Yet another variant of the uncinate process configuration is its extension superiorly to the roof of the anterior ethmoid sinus causing the superior infundibulum to end as a “blind pouch.” This continuation of the uncinate is referred to as lamina terminalis. In these causes, the infundibulum drains via the posterior aspect of the middle meatus.

The uncinate process may also become pneumatized, a condition referred to as uncinate bulla (Figures 4.18 and 4.19). Uncinate bulla is considered a predisposing factor for impaired sinus ventilation in the anterior ethmoid, frontal recess, and infundibular regions. Functionally, the pneumatized uncinate process resembles concha bullosa and is believed to be an extension of the agger nasi cell within the anterosuperior portion of the uncinate process.

Deviation

The uncinate process is one of the crucial bony structures of the wall of the lateral nasal cavity. The uncinate process together with the ethmoid bulla form the boundaries of the hiatus semilunaris and ethmoid infundibulum, the structures through which the frontal and maxillary sinuses drain. It is the free edge of the uncinate process that may vary in configuration. Medial and lateral deviation of uncinate process may cause narrowing or obstruction of the middle meatus, the hiatus semilunaris, and infund/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses