Periodontal Treatment for Older Adults

Older adults are expected to compose a larger proportion of the population than in the past. Population growth among long-lived older adults contributes to this increase worldwide. For dentistry, this means that older adults are retaining more of their natural dentition. Currently, almost 70% of older adults in the United States have natural teeth.27 However, retention of teeth may result in more teeth at risk for periodontal disease, and thus the prevalence of periodontal disease may be associated with aging. This association was addressed by Beck20 at the 1996 World Workshop on Periodontics: “It may be that risk factors do change as people age or at least the relative importance of risk factors change.”

The Aging Periodontium

Intrinsic Changes

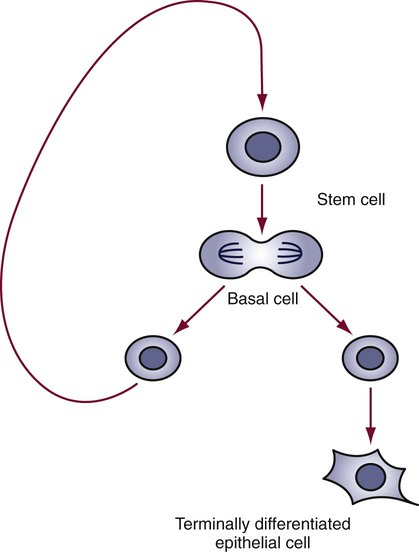

By definition, this differentiated cell, or epithelial cell, can no longer divide. Conversely, the basal cell remains as part of the progenitor population of cells ready to return to the mitotic cycle and again produce both types of cells. Thus there is a constant source of renewal (Figure 39-1). In the aging process, cell renewal takes place at a slower rate and with fewer cells, so the effect is to slow down the regenerative processes. As the progenitor cells wear out and die, there are fewer and fewer of these cells to renew the dead ones. This effect is characteristic of the age-related and biologic changes that occur with aging.

Demographics

Population Distribution

In 2010, adults 65 years of age and older were 12.0% of the U.S. population or 40 million people. By 2050, this population will grow 55% to 88.5 million people due to aging of the baby boomer generation and immigration into the United States. The greatest percentage of population growth will occur in those aged 85 and older (29%) and those 100 and older (65%). At the same time, the U.S. population is expected to increase from 312 million to 439 million or by 40%. Of the 65+ age group, the number of those 85 and older are expected to increase by 13.3 million people (300%) with centenarians (age 100+) increasing by 500,000 people or at a rate of 20 times greater than that of other segments of the aging population (900%).62,63

The increase in the aging population is the result of the dramatic increase in life expectancy during the past and present centuries. Average life expectancy was 77 years in 2010, an increase of 30 years since 1900. In 2010, life expectancy (at birth) was projected to be 80 years. Adults who reached the age of 65 in 2010 could expect to live an average of 18 additional years.62,63

Differences in population growth between urban and rural older adults have special significance for oral health. The expected increase in the proportion of older adults will be 3% larger in rural areas. Because rural older adults use dental services less than their urban counterparts, the risk for adverse changes in oral health and self-care may be greater.67

Health Status

Increased life expectancy has changed the way the public and healthcare policy makers and providers think about “aging.” Instead of controlling chronic disease and morbidity, aging is seen in terms of “successful aging” or “healthy aging.” This paradigm shift is based on study of what promotes health and longevity. Current research is now examining aging in terms of the physical, mental, and social well-being of older adults, not just disease or morbidity. The MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging asked the fundamental question, “What genetic, biomedical, behavioral, and social factors are crucial to maintaining health and functional capacities in the later years?”42

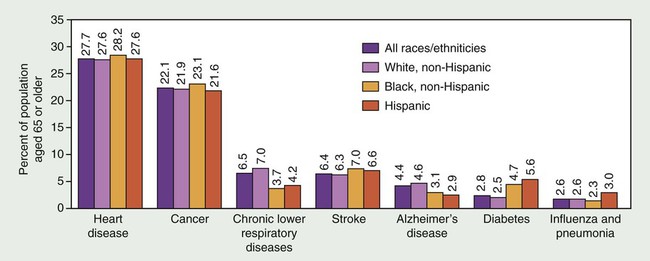

Despite this paradigm shift, the number of older adults with acute and chronic diseases continues to increase.63 Visual impairments, cataracts, glaucoma, and hearing impairments increase in frequency with advancing age. Almost half of people age 65 and older have arthritis.65 Most older adults have at least one chronic condition, and many have several chronic conditions. In 1994 the chronic conditions that occurred most often in older adults were arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, hearing impairment, cataract, orthopedic impairment, sinusitis, and diabetes (Figure 39-2). Although heart disease remains the leading cause of death among older adults, cancer may become the leader during the twenty-first century. Currently, among older adults, approximately 7 in 10 deaths are caused by heart disease, cancer, or stroke.63

In the early 1900s, Dr. Ignatz Leo was the first to recognize that older adults had health needs and concerns that set them apart from younger adults.47 Not until the latter half of the twentieth century, however, did geriatrics (medicine for older adults) become a discipline in healthcare. A “geriatric” patient is an older adult who is frail, dependent, or both and who requires health and social support services to attain an optimal level of physical, psychologic, and social functioning. Thus the treatment plan must reflect the professional knowledge to resolve physical and psychologic aspects of health status, as well as being sensitive to an individual’s all-encompassing social functioning. This functioning may include aspects of race, ethnicity, culture, personal relationships, esthetics, and social and economic conditions.

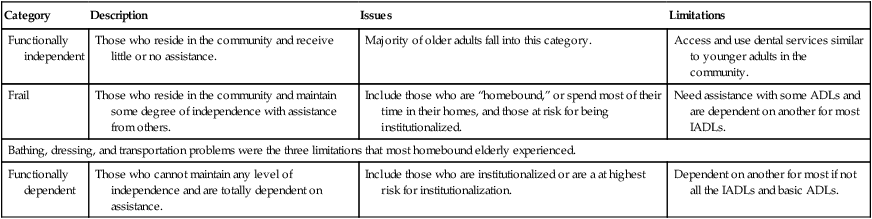

The main focus of geriatrics is frail and functionally dependent older adults. Functionally independent older adults are included but only to make them aware of services that they may need if they experience functional deficits that impair their daily activities (Table 39-1). Specialists in geriatric medicine, geriatricians, have additional training in healthcare for frail and functionally dependent older adults. In geriatric medicine, numerous assessment instruments have been developed to assist the geriatrician, and some aspects of these are important to dentists in identifying risks and functional declines. These instruments include activities of daily living (ADLs), Tinetti Balance and Gait Evaluation, geriatric depression scale (GDS), and Mini-Mental State Questionnaire. Each assesses risks to morbidity and mortality in maintaining a patient’s optimal health and functional independence.

TABLE 39-1

Functional Categories for Older Adults

| Category | Description | Issues | Limitations |

| Functionally independent | Those who reside in the community and receive little or no assistance. | Majority of older adults fall into this category. | Access and use dental services similar to younger adults in the community. |

| Frail | Those who reside in the community and maintain some degree of independence with assistance from others. | Include those who are “homebound,” or spend most of their time in their homes, and those at risk for being institutionalized. | Need assistance with some ADLs and are dependent on another for most IADLs. |

| Bathing, dressing, and transportation problems were the three limitations that most homebound elderly experienced. | |||

| Functionally dependent | Those who cannot maintain any level of independence and are totally dependent on assistance. | Include those who are institutionalized or are a at highest risk for institutionalization. | Dependent on another for most if not all the IADLs and basic ADLs. |

Care for geriatric patients crosses many disciplines. Thus, an interdisciplinary team is formed to care for and treat geriatric patients and may include the dentist. Including dentistry in the interdisciplinary effort has benefits for the patient; for example, oral care has been incorporated into nursing educational programs and practice for the geriatrician nurse practitioner.49 Likewise, dieticians have educational content in oral care. The focus is to include oral health as part of medical nutrition therapy (MNT) in achieving the patient’s total health needs.7 A “last frontier” for the interdisciplinary team is the community. When geriatric patients require multidisciplinary strategies to improve their conditions at the community level, efforts have been less than satisfactory. Problems have been encountered when coordination is needed for geriatric patients to access multiple providers across a range of healthcare settings. Shared decision making and patient education are needed to improve access and realize successful outcomes.33 A detailed computer-based model on multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary decision making in the geriatric population can be found in Bauer et al.13–19

Functional Status

In dentistry, prevention of oral diseases and improvements in healthy lifestyles have contributed to older adults keeping and maintaining their dentition. Dentistry for geriatric patients, or geriatric dentistry, emphasizes an interdisciplinary approach to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of dental and oral diseases.31 Specialists in geriatric dentistry are geriatric dentists. Similar geriatric health and functional instruments used in medicine assist geriatric dentists in assessing risks that compromise oral health.

Functional impairments have a significant impact on oral health and self-care. Sensory impairments and arthritis make it more difficult for older adults to understand dental outcomes, communicate oral healthcare needs and concerns, and perform effective oral self-care. Functional testing or measuring instruments may become part of the dentist’s armamentarium to assess an older adult’s ability to perform oral care tasks in achieving and maintaining oral health. The index of Activities of Daily Oral Hygiene (ADOH) is one such dental assessment instrument that quantifies the functional ability of older adults, specifically frail and functionally dependent older adults, in performing oral self-care tasks.10 The index of ADOH provides the dentist or dental assistant with the means to determine the functional ability of an older adult to manipulate aids used in daily oral hygiene care. From these findings, strategies may be developed to rehabilitate and then remeasure for improvements in functional deficits. If improvements are not forthcoming, alternative strategies and assistive devices are recommended.

Accommodating dentists in the interdisciplinary team is increasing, including their participation in primary care. For example, edentulism and denture wearing in older adults may be related to poor quality of life and risk for undiagnosed oral disease. They may also indicate other medical comorbidities. Thus medical and dental geriatricians must incorporate knowledge of comorbidities to identify risks that manifest as reciprocation of disease and poor quality of life.68,73 In managing periodontal disease, the dental geriatrician is challenged with integrating primary care, oral health, and patient and caregiver education in nontraditional settings such as residential, institutional, and hospital practice settings.

Although geriatric medicine training programs have grown remarkably over the past three decades, this growth is still not producing the number of geriatricians needed to care for the growing older adult population. Comparatively, the training of dental geriatricians is much less. In response, the geriatric dentistry community has advocated the use of dental geriatricians to train general dentists in the care of geriatric dental patients. Kayak and Brudvik40 see this type of training essential to “successful aging” and periodontal healthcare in both dental practice and nontraditional settings. Thus dental geriatricians as faculty are needed to train practitioners.68

In an article on periodontal dental education, Wilder et al stated “that dental schools are confident about the knowledge of their students regarding oral-systemic content. However, much work is needed to educate dental students to work in a collaborative fashion with other healthcare providers to co-manage patients at risk for oral-systemic conditions.”75

Nutritional Status

In addition, impaired chewing can cause changes in food selection, such as decreasing the variety in the diet, which may contribute to nutritional problems. Currently, 42% of older adults have no natural teeth. Rehabilitation with complete dentures may restore only 25% of normal chewing effectiveness.54 Of those with teeth, 60% have tooth decay and 90% have periodontal disease, which may contribute to impaired chewing ability or loss of appetite.

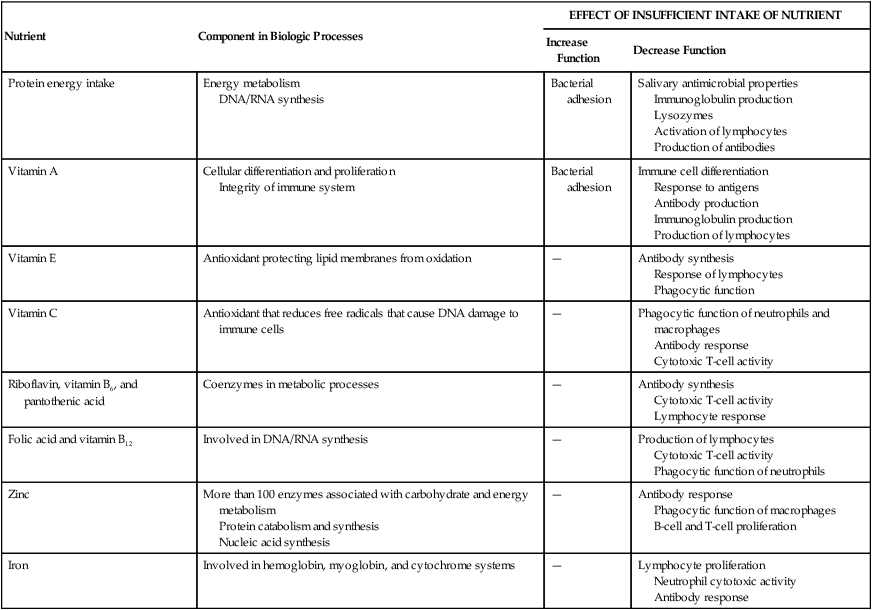

These aging-related disease states and social factors may result in inadequate consumption of nutrient-dense foods or inadequate intake of some vitamins and minerals. Minerals are important to the absorption and utilization of vitamins. Both are important to antibody formation and the immune system in combating infection, foreign substances, and toxins (Table 39-2).23

TABLE 39-2

Nutrient Effects on the Immune Response

| Nutrient | Component in Biologic Processes | EFFECT OF INSUFFICIENT INTAKE OF NUTRIENT | |

| Increase Function | Decrease Function | ||

| Protein energy intake | Energy metabolism DNA/RNA synthesis |

Bacterial adhesion | Salivary antimicrobial properties Immunoglobulin production Lysozymes Activation of lymphocytes Production of antibodies |

| Vitamin A | Cellular differentiation and proliferation Integrity of immune system |

Bacterial adhesion | Immune cell differentiation Response to antigens Antibody production Immunoglobulin production Production of lymphocytes |

| Vitamin E | Antioxidant protecting lipid membranes from oxidation | — | Antibody synthesis Response of lymphocytes Phagocytic function |

| Vitamin C | Antioxidant that reduces free radicals that cause DNA damage to immune cells | — | Phagocytic function of neutrophils and macrophages Antibody response Cytotoxic T-cell activity |

| Riboflavin, vitamin B6, and pantothenic acid | Coenzymes in metabolic processes | — | Antibody synthesis Cytotoxic T-cell activity Lymphocyte response |

| Folic acid and vitamin B12 | Involved in DNA/RNA synthesis | — | Production of lymphocytes Cytotoxic T-cell activity Phagocytic function of neutrophils |

| Zinc | More than 100 enzymes associated with carbohydrate and energy metabolism Protein catabolism and synthesis Nucleic acid synthesis |

— | Antibody response Phagocytic function of macrophages B-cell and T-cell proliferation |

| Iron | Involved in hemoglobin, myoglobin, and cytochrome systems | — | Lymphocyte proliferation Neutrophil cytotoxic activity Antibody response |

DNA, Deoxyribonucleic acid; RNA, ribonucleic acid.

Data from Boyd LD, Madden TE: Dent Clin North Am 47:337, 2003.

Psychosocial Factors

Older adults with positive attitudes toward oral health have predictably better dental behaviors that translate into higher utilization rates of dental services. Positive attitudes are highly associated with educational level.12 The education level of older adults is increasing. In 1995, only 64% of noninstitutionalized older adults completed at least high school, and 13% possessed a bachelor’s degree. By 2015, it is estimated that 76% of older adults will have completed at least high school, with 20% obtaining a bachelor’s degree. Those with more education were three to four times more likely to have visited a dentist in the past year, indicating that an informed and knowledgeable public provides a culture of healthy behaviors that guide older adults toward the long-term preservation of teeth and function.

Impediments to the utilization of dental services are associated with low income and an associated lack of a regular source of care. Those with higher education tend to be better off financially than those with low education. Poverty is less prevalent today among older adults for all race, gender, and ethnic groups.63,64 In general, older adults have the highest disposable income of all ages.71 Thus higher educational achievement with lower poverty levels is a predictor for an increase in demand for oral healthcare among older adults.39

However, differences in the prevalence of periodontal disease were seen in relation to race. Among dentate non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, and Mexican Americans 50 years of age and older, blacks had higher levels of periodontal disease, even those in higher income groups. Thus Borrell et al22 suggested that race and ethnicity are important factors in combating health disparities.

Both systemic health and quality of life are compromised when edentulism, xerostomia, soft tissue lesions, and poorly fitting dentures affect eating and food choices. Conditions, such as oral clefts, missing teeth, severe malocclusion, and severe caries, are associated with feelings of embarrassment, withdrawal, and anxiety. Oral and facial pain from dentures, temporomandibular joint disorders, and oral infections affect social interaction and daily behaviors.38

The patterns of drinking and alcohol-related problems may not differ between older and younger problem drinkers. However, numerous reports suggest that alcohol as the primary substance of abuse is higher in the older than in the younger adult. A peak onset for alcohol-related problems is 65 to 74 years. Unfortunately, alcohol consumption is directly correlated with clinical attachment loss in periodontal disease.61

Periodontal disease may also be exacerbated in those with depression.4,41 Depression is a common public health problem among elderly persons, affecting 15% of adults over age 65 in the United States. The suicide rate for those older than 85 is about 2 times the national rate. Geriatric depression is treatable, so recognition of this disorder is a vital step in the prevention of disability and mortality.56 However, depression is not easy to recognize. Depression may also accompany a wide variety of physical illnesses such as fatigue, poor appetite, sleep disturbances, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. It may be the primary cause of somatic complaints, including oral discomfort. The classic signs and symptoms for depression include sadness, decreased appetite, weight loss, confusion, difficulty in decision making, dissatisfaction, and irritability. Many older adults, however, present with a less dramatic level of actual sadness and frequently have apparent cognitive impairment, especially memory deficits, and therefore differentiation from dementia is important. Recognizing the signs of depression can significantly reduce depression, by about 70%, in those older than 65 years of age.

Dentate Status

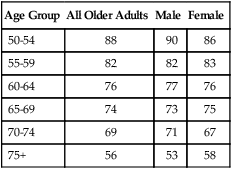

Over a 30-year period, edentulism and partial tooth loss declined substantially.27 The most current estimates of tooth loss and tooth retention in the U.S. population indicate that 75% of older adults age 65 to 69 and more than half of adults age 75 and older are dentate (Table 39-3).

TABLE 39-3

Percentage of Dentate Older Adults: United States, 1988 to 1991

| Age Group | All Older Adults | Male | Female |

| 50-54 | 88 | 90 | 86 |

| 55-59 | 82 | 82 | 83 |

| 60-64 | 76 | 77 | 76 |

| 65-69 | 74 | 73 | 75 |

| 70-74 | 69 | 71 | 67 |

| 75+ | 56 | 53 | 58 |

Data from U.S. Census Bureau: US interim projections by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin, 2004: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/.

By the year 2030, the number of teeth retained by older adults is expected to double, which is an estimated 800 million increase in tooth retention. It is expected that over the next 3 decades the average number of retained teeth will increase from the current 20 to 25.9 teeth.30 Thus the risk of periodontal disease and dental caries is expected to be a major problem of older adults. Because few older adults are covered by dental insurance,11 payment for treatments will be the responsibility of the geriatric patient. Costs and the inability to afford care will always affect healthcare utilization, particularly dentistry, which is often considered discretionary.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses