Determination of Prognosis

Definitions

Prognosis is often confused with the term risk. Risk generally deals with the likelihood that an individual will develop a disease in a specified period (see Chapter 5). Risk factors are those characteristics of an individual that put the person at increased risk for developing a disease (see Chapter 4). In contrast, prognosis is the prediction of the course or outcome of a disease. Prognostic factors are characteristics that predict the outcome of disease once the disease is present. In some cases, risk factors and prognostic factors are the same. For example, patients with diabetes or patients who smoke are more at risk for acquiring periodontal disease, and once they have it, they generally have a worse prognosis.

Types of Prognosis

Although some factors may be more important than others when assigning a prognosis1,2 (Box 33-1), consideration of each factor may be beneficial to the clinician.

Historically, prognosis classification schemes have been designed based on studies evaluating tooth mortality.1,3–6 One scheme1,5 assigns the following classifications:

Good prognosis: Control of etiologic factors and adequate periodontal support ensure the tooth will be easy to maintain by the patient and clinician.

Fair prognosis: Approximately 25% attachment loss and/or Class I furcation involvement (location and depth allow proper maintenance with good patient compliance).

Poor prognosis: 50% attachment loss, Class II furcation involvement (location and depth make maintenance possible but difficult).

Questionable prognosis: >50% attachment loss, poor crown-to-root ratio, poor root form, Class II furcations (location and depth make access difficult) or Class III furcation involvements; >2+ mobility; root proximity.

Hopeless prognosis: Inadequate attachment to maintain health, comfort, and function.

It should be recognized that good, fair, and hopeless prognoses in this classification system could be established with a reasonable degree of accuracy. However, poor and questionable prognoses were likely to change to other categories because they depend on a large number of factors that can interact in an unpredictable number of ways.7–9

In contrast to schemes based on tooth mortality, Kwok and Caton5 have proposed a scheme based on “the probability of obtaining stability of the periodontal supporting apparatus.” This scheme is based on the probability of disease progression as related to local and systemic factors (see Box 33-1). Although some of these factors may affect disease progression more than others, consideration of each factor is important in assigning a prognosis. This scheme is as follows:

Favorable prognosis: Comprehensive periodontal treatment and maintenance will stabilize the status of the tooth. Future loss of periodontal support is unlikely.

Questionable prognosis: Local and/or systemic factors influencing the periodontal status of the tooth may or may not be controllable. If controlled, the periodontal status can be stabilized with comprehensive periodontal treatment. If not, future periodontal breakdown may occur.

Unfavorable prognosis: Local and/or systemic factors influencing the periodontal status cannot be controlled. Comprehensive periodontal treatment and maintenance are unlikely to prevent future periodontal breakdown.

Overall Versus Individual Tooth Prognosis

Prognosis can be divided into overall prognosis and individual tooth prognosis. The overall prognosis is concerned with the dentition as a whole. Factors that may influence the overall prognosis include patient age; current severity of disease; systemic factors; smoking; the presence of plaque, calculus, and other local factors; patient compliance; and prosthetic possibilities (see Box 33-1). The overall prognosis answers the following questions:

• Should treatment be undertaken?

• Is treatment likely to succeed?

• When prosthetic replacements are needed, are the remaining teeth able to support the added burden of the prosthesis?

The individual tooth prognosis is determined after the overall prognosis and is affected by it.6 For example, in a patient with a poor overall prognosis, the dentist likely would not attempt to retain a tooth that has a questionable prognosis because of local conditions. Many of the factors listed under local factors and prosthetic and restorative factors in Box 33-1 have a direct effect on the prognosis for individual teeth, in addition to any overall systemic or environmental factors that may be present.

Factors in Determination of Prognosis

Overall Clinical Factors

Patient Age.

Disease Severity.

Studies have demonstrated that a patient’s history of previous periodontal disease may be indicative of their susceptibility for future periodontal breakdown (see Chapter 4). Therefore the following variables should be carefully recorded because they are important for determining the patient’s past history of periodontal disease: pocket depth, level of attachment, degree of bone loss, and type of bony defect. These factors are determined by clinical and radiographic evaluation (see Chapters 29 and 31).

Prognosis is adversely affected if the base of the pocket (level of attachment) is close to the root apex. The presence of apical disease as a result of endodontic involvement also worsens the prognosis. However, surprisingly good apical and lateral bone repair can sometimes be obtained by combining endodontic and periodontal therapy (see Chapter 43).

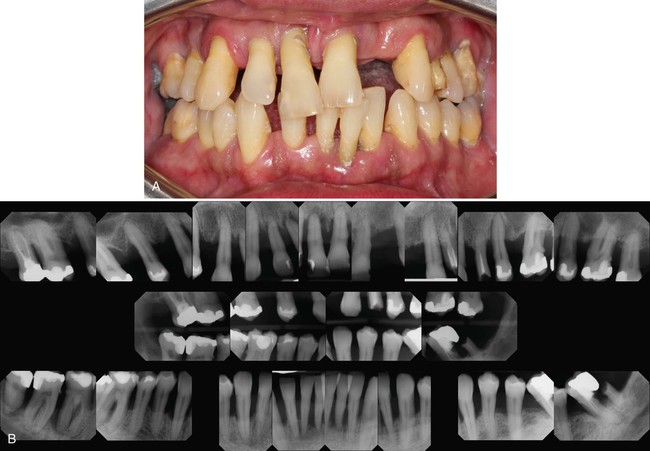

The prognosis also can be related to the height of remaining bone. Assuming bone destruction can be arrested, is there enough bone remaining to support the teeth? The answer is readily apparent in extreme cases, that is, when there is so little bone loss that tooth support is not in jeopardy (Figure 33-1), or when bone loss is so severe that the remaining bone is obviously insufficient for proper tooth support (Figure 33-2). Most patients, however, do not fit into these extreme categories. The height of remaining bone is usually somewhere in between, making bone level assessment alone insufficient for determining the overall prognosis.

The type of defect also must be determined. The prognosis for horizontal bone loss depends on the height of the existing bone because it is unlikely that clinically significant bone height regeneration will be induced by therapy. In the case of angular, intrabony defects, if the contour of the existing bone and the number of osseous walls are favorable, there is an excellent chance that therapy could regenerate bone to approximately the level of the alveolar crest.10

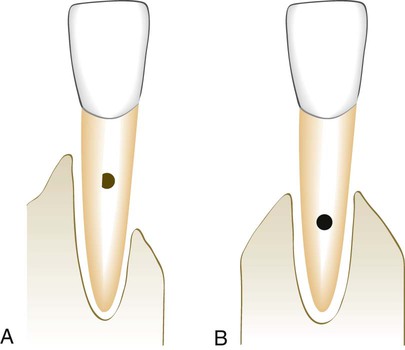

When greater bone loss has occurred on one surface of a tooth, the bone height on the less involved surfaces should be taken into consideration when determining the prognosis. Because of the greater height of bone in relation to other surfaces, the center of rotation of the tooth will be nearer the crown (Figure 33-3). This results in a more favorable distribution of forces to the periodontium and less tooth mobility.11

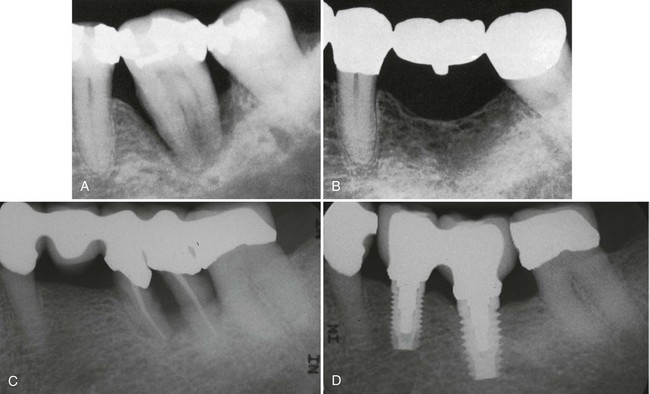

In dealing with a tooth with a questionable prognosis, the chances of successful treatment should be weighed against any benefits that would accrue to the adjacent teeth if the tooth under consideration were extracted. Strategic extraction of teeth was first proposed as a means of improving the overall prognosis of adjacent teeth and/or enhancing the prosthetic treatment plan.12 It has now been expanded to include the extraction of teeth with a questionable prognosis to enhance the likelihood of partial restoration of the bone supporting of the adjacent teeth (Figure 33-4, A to D) or successful implant placement. With the growing evidence of the long-term success of dental implants, it is proposed that a “watch and wait” approach may allow an area to deteriorate to the point that placing an implant is no longer a viable option. This means that the practitioner should weigh the potential success of one treatment option (extraction and implant placement) versus the other (periodontal therapy and maintenance) carefully when assigning a prognosis to questionable teeth.13

Systemic and Environmental Factors

Smoking.

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that smoking may be the most important environmental risk factor impacting the development and progression of periodontal disease (see Chapter 10). Therefore it should be made clear to the patient that a direct relationship exists between smoking and the prevalence and incidence of periodontitis. In addition, patients should be informed that smoking affects not only the severity of periodontal destruction but also the healing potential of the periodontal tissues. As a result, patients who smoke do not respond as well to conventional periodontal therapy as patients who have never smoked.14,15 Therefore the prognosis in patients who smoke and have slight to moderate periodontitis is generally fair to poor. In patients with severe periodontitis, the prognosis may be poor to hopeless.

However, it should be emphasized that smoking cessation can affect the treatment outcome and therefore the prognosis.16,17 Patients with slight-to-moderate periodontitis who stop smoking can often be upgraded to a good prognosis, whereas those with severe periodontitis who stop smoking may be upgraded to a fair prognosis.

Systemic Disease or Condition.

The patient’s systemic background affects overall prognosis in several ways. For example, evidence from epidemiologic studies clearly demonstrates that the prevalence and severity of periodontitis are significantly higher in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes than in those without diabetes and that the level of control of the diabetes is an important variable in this relationship (see Chapter 4). Therefore patients at risk for diabetes should be identified as early as possible and informed of the relationship between periodontitis and diabetes. Similarly, patients diagnosed with diabetes must be informed of the impact of diabetic control on the development and progression of periodontitis. It follows that the prognosis in these cases depends on patient compliance relative to both medical and dental status. Well-controlled diabetic patients with slight-to-moderate periodontitis who comply with their recommended periodontal treatment should have a good prognosis. Similarly, in patients with other systemic disorders that could affect disease progression, prognosis improves with correction of the systemic problem.

The prognosis is questionable when surgical periodontal treatment is required but cannot be provided because of the patient’s health (see Chapter 37). Incapacitating conditions that limit the patient’s performance of oral procedures (e.g., Parkinson disease) also adversely affect the prognosis. Newer “automated” oral hygiene devices, such as electric toothbrushes, may be helpful for these patients and may improve their prognosis (see Chapter 45).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses