Dental Anomalies

Ernest W.N. Lam

Dental anomalies may be congenital, developmental, or acquired and may include variations in the normal number, size, morphology, or eruptive pattern of the teeth. Congenital abnormalities are typically genetically inherited anomalies, and developmental anomalies occur during the formation of a tooth or teeth. In contrast, acquired abnormalities result from changes to teeth after normal formation. Teeth that form abnormally short roots may represent congenital or developmental anomalies, whereas the shortening of normal tooth roots by external resorption represents an acquired change.

Developmental Abnormalities

Number of Teeth

Supernumerary Teeth

Synonyms.

Synonyms for supernumerary teeth include hyperdontia, distodens, mesiodens, peridens, parateeth, and supplemental teeth.

Disease Mechanism.

Supernumerary teeth are teeth that develop in addition to the normal complement as a result of excess dental lamina in the jaws. The tooth or teeth that develop may be morphologically normal or abnormal. When supernumerary teeth have normal morphologic features, the term supplemental is sometimes used. Supernumerary teeth that occur between the maxillary central incisors are termed mesiodens, those that occur in the premolar area are peridens, and those that occur in the molar area are distodens.

Clinical Features.

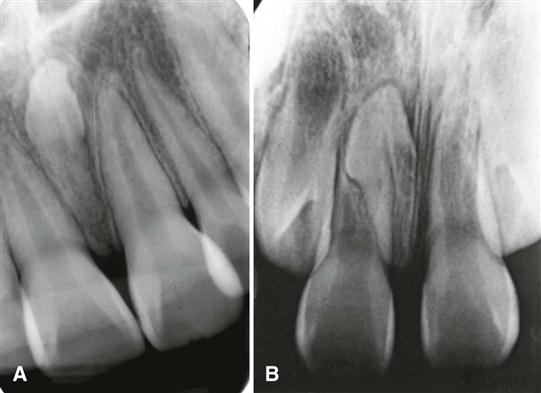

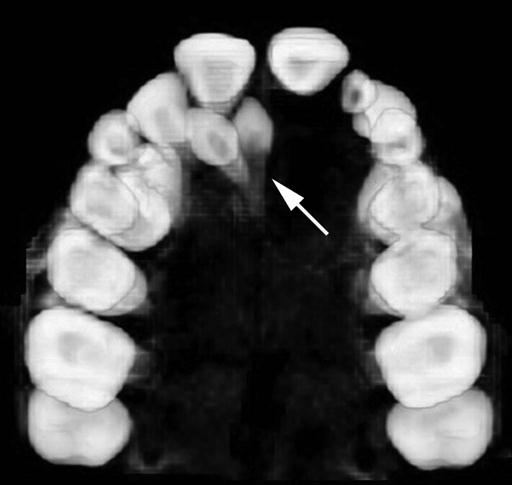

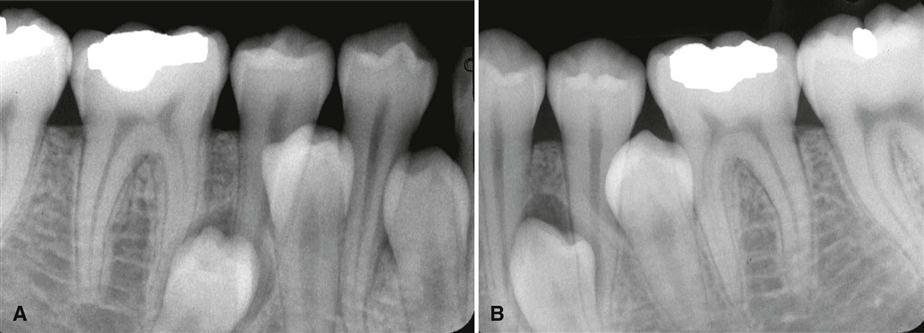

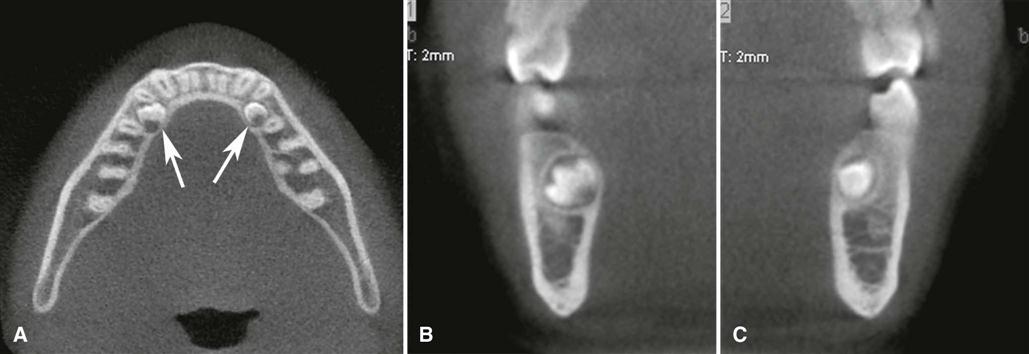

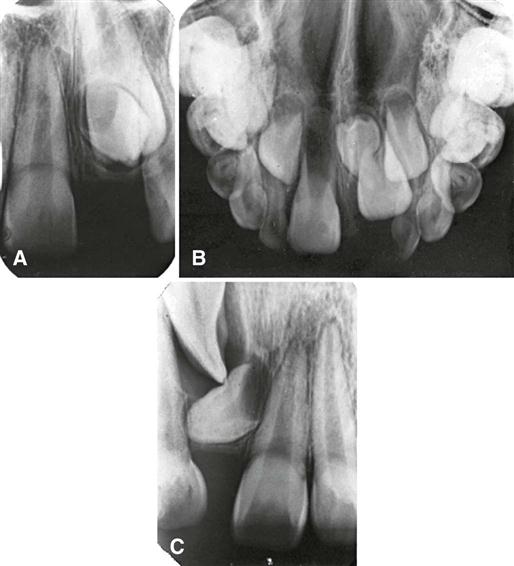

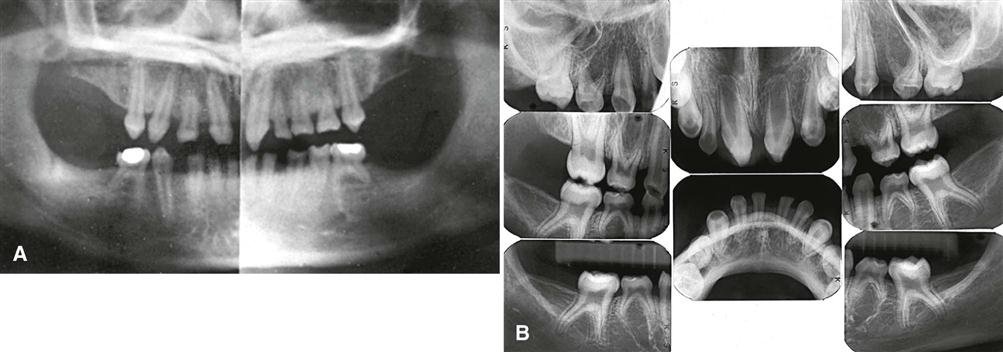

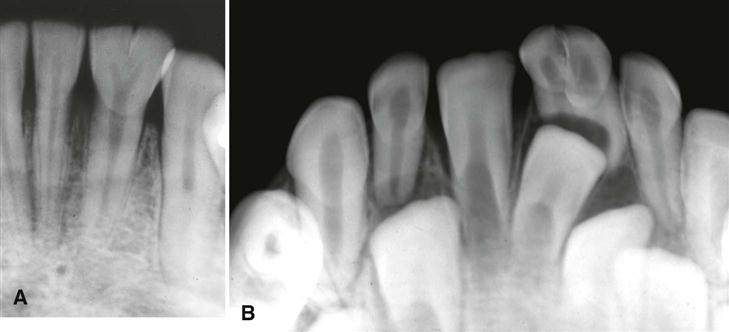

Supernumerary teeth are easily identified by counting and identifying all the teeth in the jaws. They occur in 1% to 4% of the population, may have a greater incidence in Asians and Native American and indigenous populations, and occur twice as often in males. Although supernumerary teeth can arise in either the deciduous or the permanent dentitions, they are more common in the permanent dentition and can arise anywhere in either jaw. Single supernumerary teeth are most common in the anterior maxilla, where they are referred to as mesiodens (Figs. 31-1 to 31-3), and in the maxillary molar region (Fig. 31-4), whereas multiple supernumerary teeth occur most frequently in the premolar regions, usually in the mandible and usually positioned in the lingual aspect of the alveolar process (Figs. 31-5 and 31-6).

Supernumerary teeth are usually discovered on images because they may interfere with normal tooth eruption (Fig. 31-7). When a supernumerary tooth does erupt, it commonly does so outside the normal arch form because of space restrictions.

Imaging Features.

The imaging features of supernumerary teeth are variable. They may appear entirely normal in both size and shape, but they may also be smaller in size compared with the adjacent normal dentition or have a conical shape with the appearance of a canine tooth. In extreme cases, the supernumerary teeth may appear grossly deformed.

Images may reveal supernumerary teeth in the deciduous dentition (Fig. 31-8) after 3 or 4 years of age when the deciduous teeth have formed or in the permanent dentition of children older than 9 to 12 years. In addition to periapical images, occlusal and cone-beam computed tomographic (CBCT) images may aid in determining the location and number of unerupted supernumerary teeth. Care should be taken to review panoramic images for supernumerary teeth because these may be obscured in the anterior maxillae by the image of the cervical spine, or they may appear distorted if they lie outside the focal trough.

Differential Diagnosis.

Multiple supernumerary teeth have been associated with numerous genetically inherited syndromes, including cleidocranial dysplasia (see Chapter 32), familial adenomatous polyposis (Gardner’s syndrome) (see Chapter 22), and pyknodysostosis.

Management.

The management of supernumerary teeth depends on many factors, including their potential effect on the developing normal dentition, their position and number, and the potential complications that may result from surgical intervention. If supernumerary teeth erupt, they can cause malalignment of the normal dentition. Supernumerary teeth that remain in the jaws may cause root resorption of adjacent teeth and their follicles may develop dentigerous cysts or interfere with the normal eruption sequence. All the preceding factors influence the decision either to remove a supernumerary tooth or to keep it under observation.

Missing Teeth

Synonyms.

Synonyms for missing teeth are hypodontia, oligodontia, and anodontia.

Disease Mechanism.

The expression of developmentally missing teeth includes the absence of one or a few teeth (hypodontia), the absence of numerous teeth (oligodontia), and the failure of all teeth to develop (anodontia). Developmentally missing teeth may also be the result of numerous independent pathologic mechanisms that can affect the orderly formation of the dental lamina (e.g., orofaciodigital syndrome), failure of a tooth germ to develop at the optimal time, lack of necessary space imposed by a malformed jaw, or disproportion between tooth mass and jaw size.

Clinical Features.

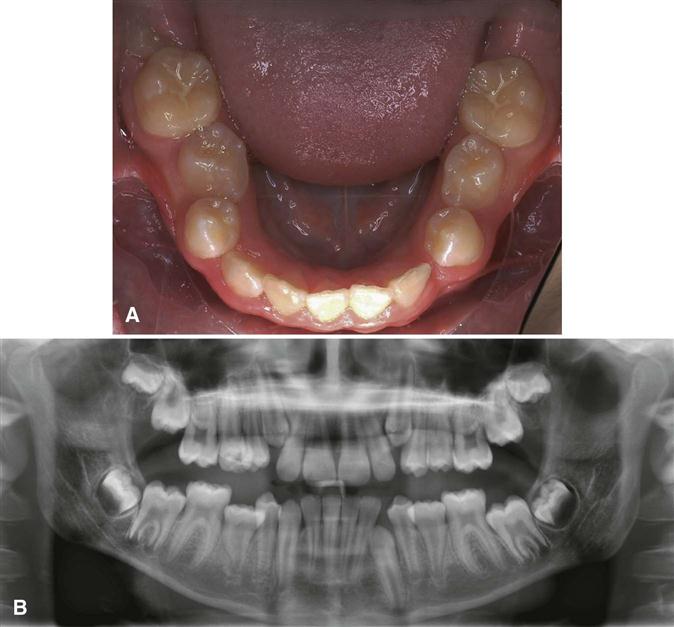

Hypodontia in the permanent dentition, excluding third molars, is found in 3% to 10% of the population. Hypodontia is more frequently found in Asian and Native American and indigenous populations. Although missing primary teeth are relatively uncommon, when one tooth is missing, it is usually a maxillary incisor. The most commonly missing teeth are third molars, followed by mandibular second premolars (Fig. 31-9) and maxillary lateral and mandibular central incisors. The absence may be either unilateral or bilateral. Children who have developmentally missing teeth tend to have more than one absent and more than one morphologic group (incisors, premolars, and molars) involved.

Imaging Features.

The development of teeth may vary markedly among individuals. Missing teeth may be recognized by identifying and counting the teeth present. For some individuals, the eruption of some teeth may be delayed by a number of years after the established time (especially mandibular second premolars), whereas others may erupt up to 1 year after the contralateral tooth.

Differential Diagnosis.

A tooth may be considered to be developmentally missing when it cannot be discerned clinically or through imaging, and no history exists of its extraction. Anodontia or oligodontia may occur in patients with ectodermal dysplasia (Fig. 31-10). This genetically diverse group of abnormalities includes 186 distinct diseases involving 64 gene mutations. In addition to missing teeth, phenotypically, these individuals may also lack sweat glands; have thin, fine hair; thin, delicate skin; and malformed nails. When the teeth are involved, the condition may manifest with multiple missing or malformed teeth that often have a conical or canine shape or a notable decrease in tooth size. The ectodermal dysplasias have been subdivided into two groups. Group A includes entities with abnormalities involving two or more of the classically involved structures previously identified, whereas group B includes abnormalities of one of these structures and another abnormality of ectodermal origin that may include the mammary glands, thyroid glands, thymus, anterior pituitary gland, cornea, conjunctiva, lacrimal gland, lacrimal duct, or meibomian glands.

Management.

Missing teeth, abnormal occlusion, or altered facial appearance may cause some patients psychological distress. If the extent of hypodontia is mild, the associated changes likewise may be slight and manageable by orthodontics. In more severe cases, restorative, implant, and prosthetic procedures can be undertaken.

Size of Teeth

A positive correlation exists between tooth size (mesiodistal or buccolingual dimension) and body height. Males also have larger primary and permanent teeth than females. Beyond these normal variations, however, individuals may occasionally have unusually large or small teeth.

Macrodontia

Disease Mechanism.

In macrodontia, the teeth are larger than normal. Macrodontia rarely affects the entire dentition. Often a single tooth, individual contralateral teeth, or a group of teeth may be involved (Fig. 31-11). Macrodontia may occur sporadically, and its cause is unknown. Vascular abnormalities such as a hemangioma (arising from within the bone or the soft tissues) can result in an increase in the size and accelerate the development of adjacent teeth. Macrodontia can also occur in hemihypertrophy of the face or in pituitary gigantism.

Clinical Features.

Clinically, macrodont teeth appear large and may be associated with crowding, malocclusion, or impaction.

Imaging Features.

Images reveal the increased size of both unerupted and erupted macrodont teeth. The shape of the tooth is usually normal, but some cases may exhibit mildly distorted morphology. Crowding may cause impaction of adjacent teeth.

Differential Diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of a sporadic macrodont tooth includes gemination and fusion. When fusion occurs, a count of the teeth present reveals a missing tooth. In gemination, all the teeth may be present, and often evidence exists of a division or cleft of the crown or root of the tooth. The differentiation between these three conditions may not influence the treatment provided.

Management.

In most cases, macrodontia does not require treatment. Orthodontic treatment may be necessary if a malocclusion is present.

Microdontia

Disease Mechanism.

In microdontia, the teeth are smaller than normal. As with macrodontia, microdontia may involve all the teeth or be limited to a single tooth or group of teeth. Often the lateral incisors and third molars may be small. Generalized microdontia is extremely rare, although it does occur in some patients with pituitary dwarfism. Supernumerary teeth may also be microdont teeth.

Clinical Features.

The involved teeth are noticeably small and may have altered morphology. Microdont molars may have an altered shape. For example, mandibular molars may have four cusps rather than five, and maxillary molars may have four cusps rather than three (Fig. 31-12). Microdont lateral incisors may be peg-shaped (Fig. 31-13).

Imaging Features.

These small teeth are frequently malformed.

Differential Diagnosis.

The recognition of small teeth indicates the diagnosis. The number and distribution of microdont teeth may also suggest consideration of syndromes (e.g., congenital heart disease, progeria).

Management.

Restorative or prosthetic treatment may be considered to create a more normal-appearing tooth, especially when considering esthetic concerns in the anterior dentition.

Eruption of Teeth

Transposition

Disease Mechanism.

Transposition is the condition in which two typically adjacent teeth have exchanged positions in the dental arch.

Clinical Features.

The most frequently transposed teeth are the permanent canine and the first premolar. Second premolars infrequently lie between the first and second molars. The transposition of central and lateral incisors is rare. Transposition can occur with hypodontia, supernumerary teeth, or the persistence of a deciduous predecessor. Transposition in the primary dentition has not been reported.

Imaging Features.

Images reveal transposition when the teeth are not in their usual sequence in the dental arch (Fig. 31-14).

Differential Diagnosis.

Transposed teeth are usually easily recognized.

Management.

Transposed teeth are frequently altered prosthetically for function or esthetics or both.

Altered Morphology of Teeth

Fusion

Synonym.

A synonym for fusion is synodontia.

Disease Mechanism.

Fusion of teeth results from the union of adjacent tooth germs of developing teeth. Some authors think that fusion results when two tooth germs develop so close together that, as they grow, they contact and fuse before calcification. Other authors contend that a physical force or pressure produced during development causes contact of adjacent tooth buds. Males and females experience fusion in equal numbers; the incidence is higher in Asian and Native American and indigenous populations.

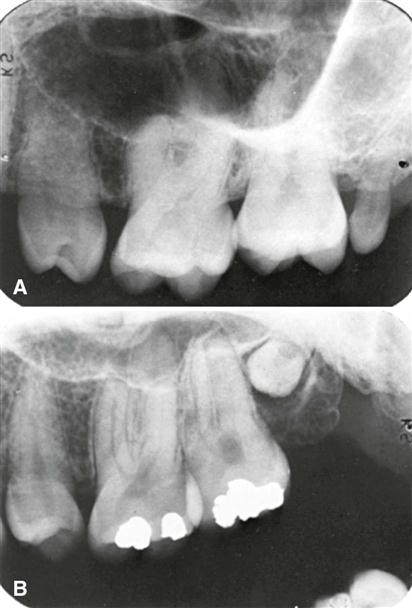

Clinical Features.

Fusion results in a reduced number of teeth in the arch. Although fusion is more common in the deciduous dentition, it may also occur in the permanent dentition. When a deciduous canine and lateral incisor fuse, the corresponding permanent lateral incisor may be absent. Fusion is more common in anterior teeth of both the permanent and the deciduous dentition (Fig. 31-15). Fusion may be total or partial, depending on the stage of odontogenesis and the proximity of the developing teeth. The result can vary from a single tooth of about normal size to a tooth of nearly twice the normal size. The crowns of fused teeth usually appear to be large and single, although incisal clefts of varying depth or a bifid crown can sometimes occur.

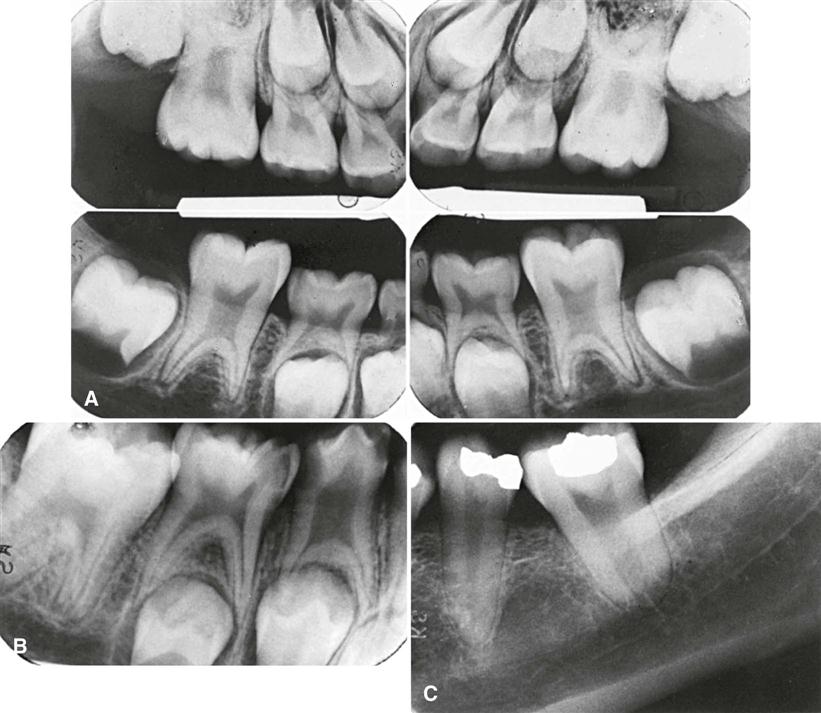

Imaging Features.

Images disclose the unusual shape or size of the fused teeth. The true nature and extent of the union are frequently more evident on the image than can be determined by clinical examination. Fused teeth may also show an unusual configuration of the pulp chamber or root canal.

Differential Diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for fused teeth includes gemination and macrodontia. Fusion may be differentiated from gemination when the number of teeth is reduced by one except in the unusual case in which a normal tooth and a supernumerary tooth have fused. The differentiation is usually academic because little difference exists in the treatment provided.

Management.

The management of a case of fusion depends on which teeth are involved, the degree of fusion, and the morphologic result. If the affected teeth are deciduous, they may be retained as they are. If the clinician contemplates extraction, it is important first to determine whether the permanent teeth are present. In the case of fused permanent teeth, the fused crowns may be reshaped with a restoration that mimics two independent crowns. The morphology of fused teeth requires radiologic examination before the teeth are reshaped. Endodontic therapy may be necessary and perhaps may be difficult or impossible if the root canals are of unusual shape. In some cases, it is most prudent to leave the teeth as they are.

Concrescence

Disease Mechanism.

Concrescence occurs when the roots of two or more primary or permanent teeth are fused by cementum. Although the cause is unknown, many authorities suspect that space restriction during development, local trauma, excessive occlusal force, or local infection after development plays an important role. If the condition occurs during development, it is sometimes referred to as true concrescence. If the condition occurs later, it is referred to as acquired concrescence.

Clinical Features.

Maxillary molars are the teeth most frequently involved, especially a third molar and a supernumerary tooth. Involved teeth may fail to erupt or may erupt incompletely. The sexes are equally affected.

Imaging Features.

An imaging examination may not always distinguish between concrescence and teeth that are in close contact or that are simply superimposed (Fig. 31-16). When the condition is suspected on an image and extraction of one of the teeth is being considered, additional projections at different angles may be obtained to delineate the condition better.

Differential Diagnosis.

It is usually impossible to determine with certainty whether teeth whose root images are superimposed are actually joined. If the roots are joined, it may be impossible to tell whether the union is by cementum or by dentin (fusion). In this regard, the absence of a periodontal ligament (PDL) space between the roots may be helpful.

Management.

Concrescence affects treatment only when the decision is made to remove one or both of the involved teeth because this condition complicates the extraction. The clinician should warn the patient that an effort to remove one might result in the unintended and simultaneous removal of the other.

Gemination

Synonym.

A synonym for gemination is twinning.

Disease Mechanism.

Gemination is a rare anomaly that arises when a single tooth bud attempts to divide. The result may be an invagination of the crown with partial division or, in rare cases, complete division through the crown and root, producing identical structures. Complete twinning results in a normal tooth plus a supernumerary tooth in the arch. The cause of gemination is unknown, but some evidence suggests that it is familial.

Clinical Features.

Although gemination may occur in both the deciduous and the permanent dentitions, it more frequently affects the primary teeth, usually in the incisor region. It can be detected clinically after the anomalous tooth erupts. The occurrence in males and females is about equal. The enamel or dentin of geminated teeth may be hypoplastic or hypocalcified.

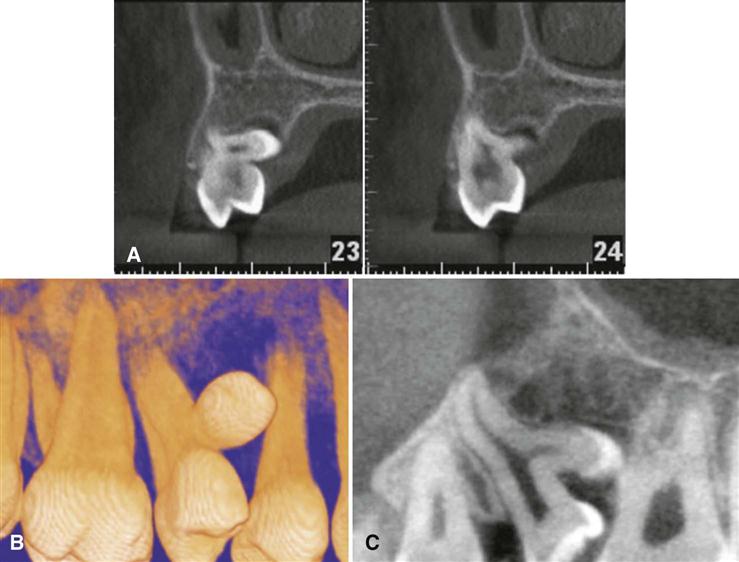

Imaging Features.

Images reveal the altered shape of the hard tissue and pulp chamber of the geminated tooth. Radiopaque enamel outlines the clefts in the crowns and invaginations and accentuates them. The pulp chamber is usually single and enlarged and may be partially divided (Figs. 31-17 and 31-18). In the rare case of premolar gemination, the tooth image suggests a molar with an enlarged crown and two roots.

Differential Diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of gemination includes fusion. If the malformed tooth is counted as one, individuals with gemination have a normal tooth count, whereas individuals with fusion are seen to be missing a tooth.

Management.

A geminated tooth in the anterior region may compromise arch esthetics and arch length. Areas of hypoplasia and invagination lines or areas of coronal separation represent caries-susceptible sites that may in time result in pulpal inflammation. Affected teeth can cause malocclusion and lead to periodontal disease. Consequently, the affected tooth may be removed (especially if it is deciduous), the crown may be restored or reshaped, or the tooth may be left untreated and periodically examined to preclude the development of complications. Before treatment is initiated on a primary tooth, the status of the permanent tooth and configuration of its root canals should be determined by imaging.

Taurodontism

Disease Mechanism.

The bodies of taurodont teeth appear elongated, and the roots are short. The pulp chamber extends from a normal position in the crown throughout the length of the elongated body, leading to a more apically positioned pulpal floor.

Taurodontism may occur in any tooth in either the permanent or the primary dentition; however, it is usually fully expressed in the molars and less often in the premolars. Single or multiple teeth may show taurodont features.

Clinical Features.

Because the body and roots of taurodont teeth lie below the alveolar margin, the distinguishing features of these teeth are not recognizable clinically.

Imaging Features.

The distinctive morphology of taurodont teeth is quite apparent on images. The peculiar feature is the elongated pulp chamber and the more apically positioned furcation (Fig. 31-19). The shortened roots and root canals are a function of the long body and normal length of the tooth. The dimensions of the crown are normal.

Differential Diagnosis.

The image of the taurodont tooth is characteristic and easily recognized on imaging. The developing molar may appear similar; however, identification of the wide apical foramina and incompletely formed roots aids in the differential diagnosis. Taurodontism has been reported with greater frequency in patients with trisomy 21 syndrome.

Management.

Taurodont teeth do not require treatment.

Dilaceration

Disease Mechanism.

Dilaceration is a disturbance in tooth formation that produces a sharp bend or curve in the tooth anywhere in the crown or the root. Although this anomaly is likely developmental in nature, one of the oldest concepts is that dilaceration is the result of mechanical trauma to the calcified portion of a partially formed tooth.

Clinical Features.

Most cases of radicular dilaceration are not recognized clinically. If the dilaceration is so pronounced that the tooth does not erupt, the only clinical indication of the defect is a missing tooth. If the defect is in the crown of an erupted tooth, it may be readily recognized as an angular distortion (Fig. 31-20).

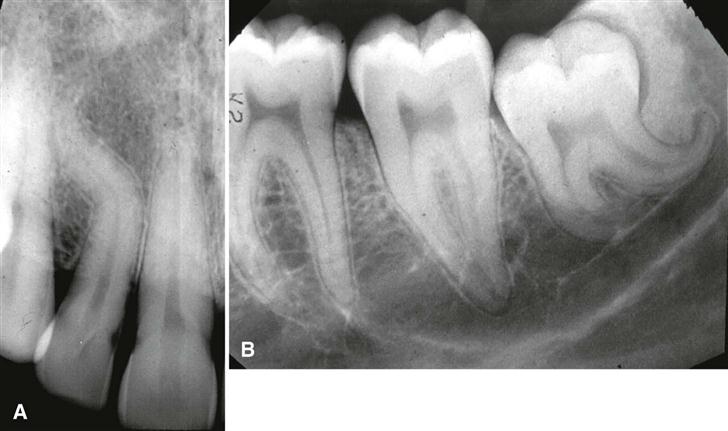

Imaging Features.

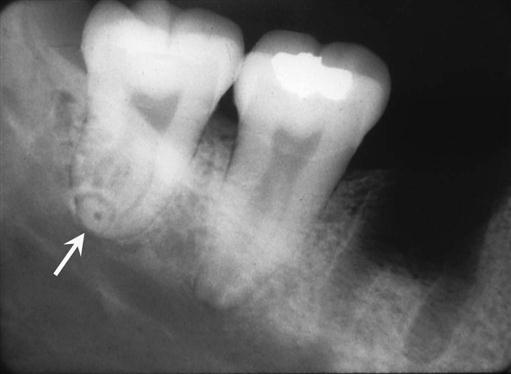

Images provide the best means of detecting a radicular dilaceration. The condition occurs most often in maxillary premolars. One or more teeth may be affected. If the roots dilacerate mesially or distally, the condition is clearly apparent on a periapical image (Fig. 31-21). However, when the roots are dilacerated buccally (labially) or lingually, the central x ray passes approximately parallel with the deflected portion of the root, and the apical end of the root may have the appearance of a circular or oval radiopaque area with a central radiolucency (the apical foramen and root canal), giving the appearance of a “bull’s eye.” The PDL space around this dilacerated portion may be seen as a radiolucent halo encircling the radiopaque area (Fig. 31-22). In some cases, especially in the maxilla, the geometry of the projections may preclude the recognition of a dilaceration.

Differential Diagnosis.

Occasionally, dilacerated roots may be difficult to differentiate from fused roots, sclerosing osteitis, or a dense bone island. However, these usually can be discerned by images made at different angles.

Management.

A dilacerated root generally does not require treatment because it provides adequate support. If the tooth is to be extracted for some other reason, the removal can be complicated, especially if the surgeon is not prepared with a preoperative image. In contrast, dilacerated crowns are frequently restored with a prosthetic crown to improve esthetics and function.

Dens Invaginatus, Dens in Dente, and Dilated Odontome

Synonyms.

Gestant odontome and “tooth within a tooth” are synonyms for dens invaginatus, dens in dente, and dilated odontome.

Disease Mechanism.

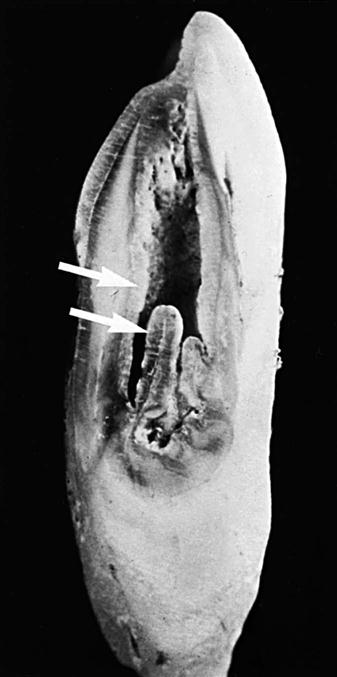

The three entities dens invaginatus, dens in dente, and dilated odontome all result from varying degrees of invagination or infolding of the enamel surface into the interior of a tooth. The least severe form of this infolding is dens invaginatus, and the most severe form is dilated odontome. The invagination can occur in either the cingulum area (dens invaginatus) or the incisal edge (dens in dente) of the crown or in the root during tooth development. It may also involve the pulp chamber or root canal system; this may result in a deformity of either the crown or the root, although these anomalies are seen most often in tooth crowns. Coronal invaginations usually originate from an anomalous infolding of the enamel organ into the dental papilla. In a mature tooth, the result is a fold of hard tissue within the tooth characterized by enamel lining the fold (Fig. 31-23). When the abnormality involves the root, it may be the result of an invagination of Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath and produce an accentuation of the normal longitudinal root groove.

In contrast to the coronal type, which is lined with enamel, the radicular type of defect is lined with cementum. If the invagination retracts and is cut off, it leaves a longitudinal structure of cementum, bone, and remnants of the PDL within the pulp canal. The structure often extends for most of the root length. In other cases, the root sheath may bud off a saclike invagination that produces a circumscribed cementum defect in the root. Mandibular first premolars and second molars are especially prone to develop the radicular variety of this invagination anomaly.

Among whites and Asians, there is little difference in frequency of occurrence. If all grades of expression of invagination—from mild to severe—are included, the condition is found in approximately 5% of these two ethnic groups. The condition appears to be rare in individuals of African descent. No sexual predilection exists. Although no specific mode of inheritance seems to fit all the data, a high degree of inheritability seems to exist.

Clinical Features.

Dens invaginatus may appear as nothing more than a small pit between the cingulum and the lingual surface of an incisor tooth (Fig. 31-24). In dens in dente, the pit is located at the incisal edge of the tooth, and crown morphology may appear abnormal, having the appearance of a peg-shaped microdont tooth (Fig. 31-25). A dilated odontome can be thought of as the most extreme dens invaginatus and has roughly the shape of a doughnut with central soft tissue surrounded by dental hard tissue.

Dens invaginatus and dens in dente occur most frequently in the permanent maxillary lateral incisors, followed by (in decreasing frequency) the maxillary central incisors, premolars, and canines and less often the posterior teeth. Invagination is rare in the crowns of mandibular teeth and in deciduous teeth. The abnormality occurs symmetrically in about half the cases, and concomitant involvement of the central and lateral incisors may occur.

The clinical importance of dens invaginatus and dens in dente is the risk of pulpal inflammation. Although enamel lines the coronal defect, it is frequently thin, often of poor quality, and even missing in some areas. The cavity is usually separated from the pulp chamber by a relatively thin wall that opens into the oral environment through a narrow constriction. The pit is often difficult if not impossible to keep clean, and consequently it offers conditions favorable for the development of caries. Carious lesions are difficult to detect clinically and rapidly involve the pulp. In addition, sometimes fine canals extend between the invagination and the pulp chamber, resulting in pulpal disease even in the absence of caries.

Imaging Features.

/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses