CHAPTER 30 The Child in Contexts of Family, Community, and Society

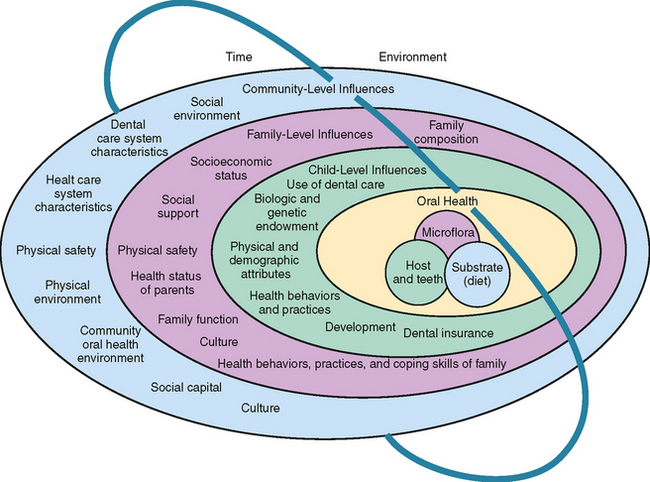

The preceding chapters delineate the range of options and opportunities available to practitioners to promote and ensure individual children’s oral health through clinical interventions. This chapter turns to the larger question of how all children’s oral health can be promoted and ensured through family, community, and society-wide population-level interventions, including governmental interventions (Fig. 30-1).

Conceptually, pediatric dentistry and public health dentistry share a unique niche within the spectrum of dental disciplines. They are the only two recognized specialties of dentistry that are essentially holistic in nature. Unlike other recognized areas of dental specialization that attend to a particular tissue, such as periodontics and endodontics, or a set of clinical techniques, such as orthodontics, prosthodontics, and oral and maxillofacial surgery, or to a diagnostic domain, such as oral pathology and oral radiology, both pediatric dentistry and public health are defined by those they serve—children in the case of pediatric dentistry and entire populations in the case of public health dentistry. For this reason, the required knowledge and skill sets needed to well manage the target population’s oral health are broad.

A quote attributed to the classical Roman poet Virgil, “as the twig is bent, the tree inclines” provides a paradigm for public health’s concern for children and their oral health. After following a cohort of 980 people from birth to age 26, researchers noted that “adult oral health is predicted by not only childhood socioeconomic advantage or disadvantage, but also by oral health in childhood.”1 Research techniques in MCH, including “social determinants of health,” “lifecourse studies,” and “common determinants of health modeling,” all suggest that conditions impacting children play out consequentially throughout life. This is particularly true of oral health in that having childhood caries, particularly early childhood caries, is the strongest indicator of lifelong caries risk. This is because the presence of early childhood caries signifies the presence of a well-established caries process that remains stable as the primary teeth exfoliate and are replaced by permanent teeth and as periodontal diseases cause recession that exposes root surfaces to caries as children age into adulthood and senescence. Similarly, genetic, environmental, behavioral, and even psychological factors strongly impact periodontal health, dental development, occlusion, the occurrence and effects of trauma, susceptibility to soft tissue lesions, and every other aspect of a child’s oral health.

CHILDREN’S ORAL HEALTH AND DENTAL CARE

While dental care is an essential component of oral health attainment and maintenance, its contribution is relatively modest compared with other oral health determinants. One effort to model the relative importance of various determinants of general health suggests that only about 10% of health status can be explained by access to health care. The remaining 90% can be attributed primarily to health behaviors and secondarily to environmental and hereditary factors.2 Such conceptual modeling has been applied to children’s oral health status to clarify the relative importance of various oral health determinants. The model shown in Fig. 30-1 lists the “use of dental care” as only one of six “child-level” factors influencing oral health along with eight “family-level influences”, eight “community-level influences,” and the ongoing impacts of time and environment on each level of influence.3 An analogous approach to explaining oral health disparities in children considers four levels of influence: (1) “macro” factors as wide ranging as the natural environment and dental care systems that are available to children; (2) “community” factors that include the social/cultural environment and availability of dental services; (3) “interpersonal” factors involving social stressors, integration, and support; (4) “individual” factors of biology, health behaviors, care-seeking behaviors, and psychological considerations.4

Such models help clinicians understand the range of factors that they can, and cannot, manage or influence in seeking to help each child and each child’s family obtain and maintain excellent oral health. The technical content of clinical care is entirely within the scope of clinical dental practitioner. However, key approaches to children’s dental care, including anticipatory guidance, primary prevention through modification of health behaviors, disease suppression through individually tailored disease management plans, and encouraging compliance with professional recommendations, all move the clinician away from the biologic sciences and their technical correlates and into the realms of social and behavioral sciences and their roles in health education and health promotion. These “soft” disciplines have equal relevance for the oral health of individuals and populations. The dentist who seeks to improve children’s oral health must therefore rely equally on clinical and public health interventions that are based on both “hard” and “soft” science.

DISEASE BURDEN

The term disease burden implies the volume and distribution of disease within a population as well as its consequences in terms of morbidity and mortality. Dental caries remain highly prevalent worldwide (Fig. 30-2). In the United States and other countries, it is the most prevalent childhood chronic illness. It is disproportionately a disease of poverty, minority, and social disadvantage (Fig. 30-3). In the United States, for example, information prepared for the U.S. Surgeon General’s Workshop on Children and Oral Health in 2002 reported profound disparities in both oral health status and access to dental care by age, income, race, and parental education5 (Table 30-1). That report predicted that epidemiologic and demographic trends would drive childhood caries experience higher and would lead to additional stress on the dental delivery system that attends to poor and low-income children. Since that time, disease burden and inequities in its distribution have increased among young children. More U.S. children were born in 2007 than at the peak of the “baby boom” and further growth is anticipated to be disproportionate among minority, poor, and single-parent families whose children also experience higher caries rates and lower treatment rates. While caries experience among older children has declined, caries experience among 2- to 5-year-olds is at a record level of 28%, suggesting additional future stress on dental care capacity. Possible explanations for increasing disease burden among young children include nonclinical factors, among which are demographic changes, lesser availability of fluoride exposure because of increased use of nonfluoridated bottled water, changes in parenting styles and practices, and temporal changes in dietary practices. Dental service rates continue to be highest for children from higher income families while the publicly funded dental programs for poor and low-income children (Medicaid and the State Child Health Insurance Program), despite improvements, continue to reach only about a third of enrolled low- and modest-income children with dental services.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses