3

Transition from the Natural to the Artificial Dentition

The loss of the remaining natural teeth and provision of an artificial dentition is a major and irreversible procedure for the patient. The enormity of the change raises the question – why is it not more common to use overdentures over natural tooth remnants, at least as a staging post, in the transition to the edentulous state? This is particularly the case as such overdentures may last for so long that the patient is able to continue having the denture supported by these natural abutments for the rest of his or her life. The question as to why this transition is not more frequently used is brought into sharp focus when one considers the improvements seen in patient satisfaction and quality of life provided by implant-supported overdentures when compared with conventional dentures (Thomason 2007). Before discussing the various ways of making the transition, it is helpful to consider just how common is the sudden, complete transition to the edentulous state and the typical reaction that patients have to the prospect.

Regular national surveys of the dental health of adults enable us to examine the changing state of dentitions and the attitudes of people to their dental status (Todd & Lader 1991; Walker & Cooper 2000). The general improvement in oral health has already been described in Chapter 1. With respect to the transition, there have been parallel improvements with the loss of natural teeth becoming an increasingly gradual process. For example, whereas in 1978 two-thirds of those who had lost the remainder of their teeth had 12 or more teeth extracted at the final stage, this proportion was reduced to nearly half in the next decade and to a quarter in the 1990s.

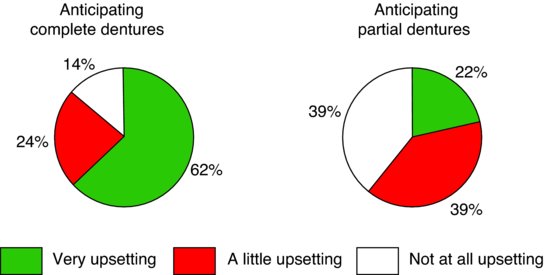

The level of anxiety with which people face the prospect of losing all their teeth and having to rely on complete dentures can be seen in Fig. 3.1. Nearly two-thirds of those people who did not wear dentures of any kind found the thought of having to wear complete dentures very upsetting. The concern was felt more by women than by men and more by those people who were regular attenders for dental treatment. It is important that the clinician appreciates that the transition can be a cause of great concern to the patient and takes the opportunity not only to manage this transition with understanding but also to offer alternatives to simply rendering the patient edentulous.

Figure 3.1 The attitude of adults (%) with only natural teeth to the thought of having complete dentures or a removable partial denture. (From Todd & Lader, 1991.)

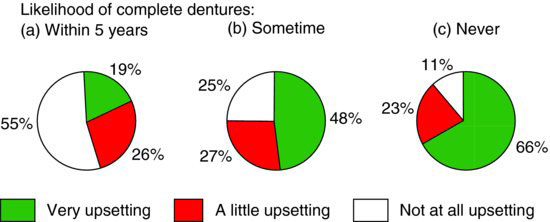

Figure 3.2 The attitude of adults (%) with only natural teeth to the thought of having complete dentures by the likelihood that they will need them. (From Todd & Lader, 1991.)

It can also be seen in Fig 3.1 that the concern about having complete dentures is much greater than that about partial dentures. Another important point to make is that this attitude had become more widespread over a 10-year period between surveys to the extent that the proportion of those who viewed the thought of having complete dentures as a very upsetting experience had gone up by 10%.

The level of concern felt by the general public can be examined in another way (Fig. 3.2). Here the level of anxiety was gauged amongst those who thought they were likely to need complete dentures within 5 years, those who would need complete dentures at sometime in the future and those who felt they would never require complete dentures. As expected, the proportion of those who were very upset about the prospect of having complete dentures increased as their expectations of keeping their natural teeth increased. But even amongst those who thought they would need complete dentures in the next 5 years, one in five viewed the prospect as a very upsetting experience.

What is quite apparent is that a significant proportion of people who may have to have their remaining teeth extracted and complete dentures provided view the prospect with a great deal of concern and anxiety, thus making their acceptance of treatment much harder (see Chapter 2). The aim of this chapter is to outline the principles of treatment contributing to a successful transition either when forced to remove all the remaining tooth elements, or better still when at least some roots can be retained as overdenture abutments. The use of implants in place of tooth roots to support and stabilise the lower denture is also considered. Details of clinical techniques are, in the main, omitted.

Methods of transition

The various methods of making the transition from natural to artificial dentition may be considered under the following headings.

Transitional partial dentures

Transitional partial dentures restore existing edentulous areas. They may be worn for a short period of time before the remaining natural teeth are extracted and the dentures are converted accordingly.

Overdentures

Overdentures are fitted over retained roots and derive some of their support and, if appropriately contoured, some stability from that coverage. Special attachments may be fixed to the root faces to provide mechanical retention for the denture which will further increase the denture stability. If, in due course, the roots have to be extracted, the overdenture can be converted into a mucosally-supported complete denture. In addition, overdentures can be supported and retained by implants.

Immediate dentures

Immediate dentures are constructed before the extraction of the natural teeth and are inserted immediately after removal of those teeth. An immediate denture can be either a conventional complete denture without support from the tooth roots, or a complete immediate overdenture.

Clearance of remaining natural teeth before making dentures

This approach differs from all those mentioned previously in that, after the extractions, time is allowed for initial healing and alveolar bone resorption to occur before providing complete dentures.

Factors influencing the decision of whether to extract all the remaining teeth or to retain some teeth or tooth roots

When the patient’s dentition has reached the stage where it appears that complete dentures will be necessary in the foreseeable future, the clinician must consider carefully the timing of extraction of the remaining teeth and if it would be possible to retain some tooth roots, even if only in the short term. The following considerations will influence the decision.

The condition of the teeth and supporting tissues

The prognosis for each remaining tooth should be assessed carefully. Useful teeth can be retained if:

- it is feasible to undertake appropriate treatment to eliminate any disease present;

- if there is confidence in the patient’s ability to maintain good, or even reasonable, oral health.

The presence of gross caries or advanced periodontal disease, coupled with an inability of the patient to maintain an acceptable level of oral hygiene, makes the decision of whether or not to extract the teeth a much simpler one; early extraction in such circumstances is probably advisable. Such a decision is perhaps especially important in the case of advanced periodontal disease where any undue delay will result in further destruction of what will become the bony denture foundation. Nevertheless, many patients who would be unwilling or unable to manage reasonable oral hygiene around multiple teeth, can often manage to clean two simple overdenture abutments, or at least to clean them well enough to delay significant short-term bone loss.

The position of the teeth

Natural teeth opposing an edentulous ridge

The situation in which one arch only is rendered edentulous can lead to major prosthetic complications. The combination most commonly found is a complete upper denture opposed by a number of lower natural teeth. A most unfavourable situation can develop in which the natural teeth generate high occlusal loads and excessive displacement of the denture, which may result in:

- rapid destruction of the denture-bearing bone;

- the production of a flabby ridge (see Chapter 16);

- complaints of a loose denture;

- a deteriorating appearance as the denture sinks into the tissues;

- fracture of the denture base.

The problems are accentuated in the lower jaw because the denture-bearing area is smaller.

Serious consideration must be given to preventing these problems from developing. The first step is to warn the patient of the possible consequences and arrange for regular inspection and maintenance to reduce the possibility of rapid, damaging resorption. If sufficient thought has been given to the problem in advance, it may be possible to utilise selected teeth as overdenture abutments so as to improve the loading on the underlying bone. It would be very rare for the clinician to consider trying to reduce the occlusal loads by extracting sound teeth in the opposing arch.

Over-eruption of the teeth

Extraction of over-erupted teeth may be required because they:

- excessively reduce the vertical space available for the opposing prosthesis;

- have a poor appearance.

In appropriate cases, endodontic therapy followed by decoronation of over-erupted teeth (so that they can be used as overdenture abutments) might be the preferred alternative approach. This also has the marked advantage that decoronating the tooth markedly improves its crown–root ratio and, therefore, creates a more favourable loading, usually resulting in a considerable reduction in mobility.

Age and health of the patient

As mentioned in Chapter 2, advancing years, frequently coupled by worsening health, may reduce the patient’s ability to adapt successfully to complete dentures. This places the clinician on the horns of a dilemma when planning the timing of the extraction of teeth that have an uncertain prognosis:

- Extract the remaining teeth earlier? On the one hand, the teeth may be expected to have a few more years of useful life, but delaying extractions until they are unavoidable may postpone the patient’s first experience of complete dentures to a time when ageing has seriously reduced adaptive capability. As a result, the patient may find it difficult, or even impossible, to cope with complete dentures when they are eventually fitted. It may therefore be argued that the best approach under such circumstances is to extract the teeth sooner rather than later so that the patient stands a better chance of adapting successfully to complete dentures. Better still, though, would be a planned progression through transitional partial dentures, the undertaking of endodontics on selected teeth for later overdenture support and eventually the conversion of the partial denture to a simple complete overdenture.

- Extract the remaining teeth later? As the rate of biological ageing and reduction in adaptive capability vary greatly from one patient to another, it is not possible to identify accurately a cut-off point in years at which extractions should be carried out for the reason outlined above. It is true that early extractions may reduce problems of adaptation to dentures, but this advantage must be balanced against the immediate probability of reduced oral function and comfort in a patient who may be happy with a few remaining natural teeth and, perhaps, a partial denture.

The correct way out of the dilemma of whether or not to take the irrevocable step of a dental clearance may be determined by delaying the decision and placing the patient on a programme of regular review appointments. At each appointment, an assessment can be made of the rate of deterioration of the patient’s dentition, and thus a clearer picture will emerge of the probable life of the teeth and their value to the patient. A somewhat crude judgement is to assess the health of the patient and the teeth and try to answer the question, ‘Is the patient likely to outlive the remaining useful natural teeth, or is the reverse more likely to occur?’ When it seems probable that the patient will outlive the remaining teeth in their current form, the first step should be the consideration of a staged transition, from partial dentures through to overdentures and, only if necessary, to conventional complete dentures. This way any decision to take action can be moderated by the patient’s response to each phase of treatment.

It is important to remember that in the very elderly patient any elective alteration of oral status must be made only when absolutely necessary. On balance, extractions should probably be carried out only when they are unavoidable, not as an elective procedure in the hope that this will reduce adaptive difficulties later. In fact, those difficulties are likely to be present already.

To this end, there is a strong argument that every effort should be made to retain useful, strategic teeth which may either help to stabilise a partial denture or be converted into overdenture abutments. The argument may be extended by saying that if these last remaining teeth are extracted, and the patient experiences enormous problems with the complete dentures, the only way of minimising these problems is to provide an implant-retained overdenture. Such treatment is more costly. Thus, retaining these few natural teeth may well save the patient considerable trouble and expense and the clinician no little heartache.

The patient’s wishes

The patient will often have views about whether or not the remaining teeth should be extracted and these views must of course be given high priority. If the views coincide with the clinician’s judgement all is well. However, the following two scenarios occur occasionally and might cause the clinician some difficulty.

Hopeless teeth that the patient wants to retain

The clinician should carefully explain to the patient about the condition of the teeth and the possible harmful consequences of retaining them. If in spite of this the patient persists in wanting to retain the teeth, the clinician can do little apart from carefully noting the situation in the patient’s record. A decision may still have to be made on whether to proceed with an alternative treatment plan, such as the provision of transitional partial dentures or an overdenture, or whether to withdraw from treatment.

Sound, useful teeth that the patient wants extracted

Again, the clinician’s primary responsibility is to explain to the patient the nature of the clinical situation and to emphasise the harm that unnecessary extraction of the remaining teeth would cause. If this is done with care, the majority of patients will be persuaded of the value of keeping the teeth, or the tooth roots where this would be more appropriate. Judging from the relatively small number of tooth-supported overdentures it would appear that this is an area that the dental profession has probably not promoted sufficiently in the past. However, even after careful explanation a few patients will not accept the case for retaining the teeth; the appropriate action by the clinician is most likely to be withdrawal from the case, as to extract the teeth without clinical justification would be unethical.

Transitional partial dentures

Transitional partial dentures are of particular value in those cases where problems of adaptation to, or tolerance of, complete dentures are anticipated. Wearing a transitional partial denture provides:

- an opportunity to complete any denture adjustments found necessary to provide comfort and adequate function, before the remaining teeth are extracted or decoronated;

- a training period that allows the patient to develop some denture control and tolerance under circumstances made less demanding by the stabilising effect of the remaining teeth.

However true this may be, a study of unsuccessful and successful complete denture wearers did not conclude that a history of wearing a partial denture had any influence on the eventual outcome (Beck et al. 1993).

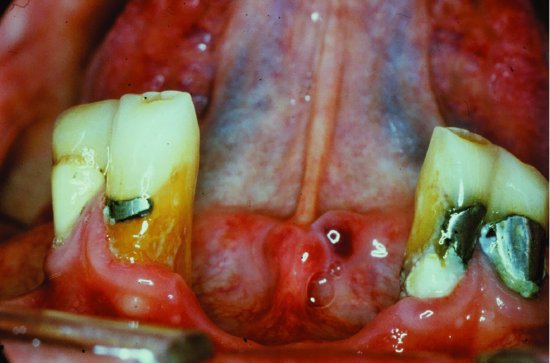

Figure 3.3 Severe tissue destruction caused by a tissue-borne partial denture.

The chance of success of a transitional partial denture is influenced to a large extent by the particular teeth that remain in the mouth. For example, stability of a lower denture will be increased if an anterior saddle is present because the existence of the labial flange and contacts with the mesial surfaces of the abutment teeth will resist posterior displacement. Also, if the denture carries anterior teeth, the patient will be better motivated by the wish to retain a good dental appearance to persevere with the denture in the face of any initial difficulties. Success is also more likely if the denture design incorporates clasps (and preferably rests) to maximise retention and support. Although transitional partial dentures are a potentially valuable means of smoothing the passage from the partially dentate to the edentulous state, they can compound the difficulties of subsequent complete dentures unless they are correctly designed and adequately maintained. A partial denture that is under-extended, poorly fitting or which has an incorrect occlusion is likely to be unstable and uncomfortable, thus undermining the patient’s confidence in denture wearing. Also, if the patient perseveres heroically with the partial denture in spite of the difficulties, destruction of the denture-bearing tissues is likely to occur, creating a more unfavourable foundation for subsequent complete dentures. Whilst traditionally these transitional partial dentures have been supported only by the soft tissues (so called tissue-borne) there is no reason why this should be the case. The important advantage of a transitional denture is that it can be added to when teeth need to be extracted; this usually means that the connector needs to be constructed from acrylic resin. It should be remembered that the transitional partial denture is the type of prosthesis usually provided for a patient whose dental awareness is highly suspect. In this situation, increased plaque formation and lack of adequate support can combine to cause severe tissue destruction in a relatively short time (Fig. 3.3). In such a case, a high-risk denture is provided for a high-risk patient.

Tooth-supported overdentures

In the transitional dentition the overdenture, like the partial denture, can be used to provide a training period, allowing the patient to prepare for the more demanding task imposed by future conventional complete dentures. If the life of the teeth is limited, treatment should normally be kept as simple as possible. However, even the simplest overdenture treatment usually entails root filling and decoronating two or three abutment teeth. As the loading of the teeth is more advantageous once they are decoronated, the simple overdenture may well extend the life of these remaining abutments. Therefore with tolerably acceptable oral hygiene, the tooth supported complete overdenture can be a long-term treatment option for many patients.

Advantages of tooth-supported overdentures

Preservation of the ridge form

Retaining the roots and periodontal tissues of the abutment teeth reduces resorption of the surrounding bone. This is the most important advantage of overdentures, particularly for the lower jaw where it has been shown that preserving the canine roots can reduce the rate of resorption in that region by a factor of 8. This preservation of alveolar bone has obvious benefits in providing support and promoting stability of dentures. If the retained roots are in the anterior region, the preservation of bone will also help to maintain support of the lips and thus will contribute to facial appearance.

Minimising horizontal forces on the abutment teeth

The reduction in crown length of the abutment teeth and the production of a domed shape to the root face reduces the mechanical advantage of potentially damaging horizontal forces. As mentioned above, the life of the abutment teeth may therefore actually be prolonged, and teeth that were very mobile before treatment commonly become firmer. This change in mobility is partly due to the improvement in the crown–root ratio. In addition, the absence of teeth on either side of these overdenture abutments facilitates oral hygiene measures which can be especially helpful for those who have found this a challenge in the past.

Proprioception

It has been suggested that while the roots and their periodontal ligaments remain, periodontal mechanoreceptors allow a finer discrimination of food texture, tooth contacts and levels of functional loading. A better appreciation of food and a more precise control of mandibular movements may therefore be possible than is provided for by receptors in the denture-bearing mucosa of edentulous patients. In theory this may mean that natural tooth roots may serve better in this regard than dental implants which are devoid of periodontal mechanoreceptors.

Correction of occlusion and aesthetics

Overdentures have a particular advantage over partial dentures in those cases where the crowns of the remaining few teeth are not ideal either in terms of occlusion or appearance. Removal of the offending crowns and covering of the roots with an overdenture provide the freedom in artificial tooth arrangement necessary to correct the undesirable features.

Denture retention

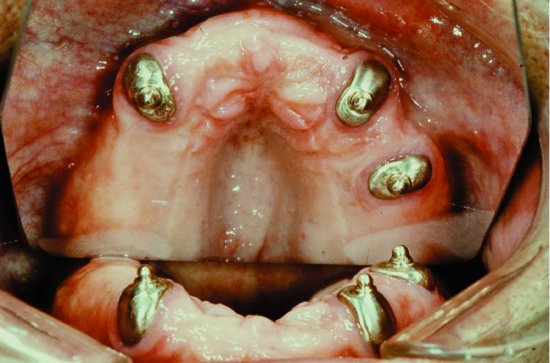

As mentioned earlier, more positive retention of the denture to the root faces may be obtained by means of precision attachments (Fig. 3.4). However, in many instances, such additional retention seems not to be needed. Indeed whilst precision attachments may make a positive contribution to retention on roots with good bone support, they are contraindicated for overdentures provided as a transitional stage of limited duration en route to conventional complete dentures for the following reasons:

Figure 3.4 Stud attachments on the abutment teeth are engaged by spring clips within the overdenture to provide positive retention.

- The increased height of the abutment arising from the precision attachment will adversely affect the crown–root ratio of the tooth. As a result, the tooth root will be subjected to larger horizontal forces.

- Attachments are relatively expensive and, therefore, may not be cost-effective if used on abutment teeth with a poor prognosis.

- The retention achieved with attachments can be too good, thus inhibiting the development of the patient’s neuromuscular skills that will be required to control the future conventional complete dentures when the loss of these roots is inevitable.

An alternative method of augmenting retention is to use rare earth magnets located in the overdenture with the keepers incorporated into the abutment teeth (Fig. 3.5). These devices are less expensive than many precision attachments and provide effective retention. As a magnet applies less lateral force to the abutment tooth than does a precision attachment, it can be used in situations where more advanced periodontal destruction has occurred.

Figure 3.5 Keepers have been placed in the abutment teeth. The rare earth magnets are located within the overdenture.

The disadvantage of early designs of rare earth magnets is that they corroded in the oral environment. There has been significant improvement in this regard over the last decade with magnets now encased in a relatively inert capsule of titanium or stainless steel. In spite of this, corrosion can still be an occasional problem with some magnets when the oral fluids diffuse through the epoxy seal of the capsule (Riley et al. 1999). Longevity is improved if the magnet is enclosed in a laser-welded stainless steel casing (Thean et al. 2001).

Psychological benefits

The complete, irrevocable loss of all teeth can be a serious blow to a patient’s morale as it signals, perhaps, that a major milestone in life has been reached. The retention of remnants of the natural de/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses