Chapter 3The Thorax

Chapter 3The Thorax

1 Skeleton and Divisions

THORACIC SKELETON

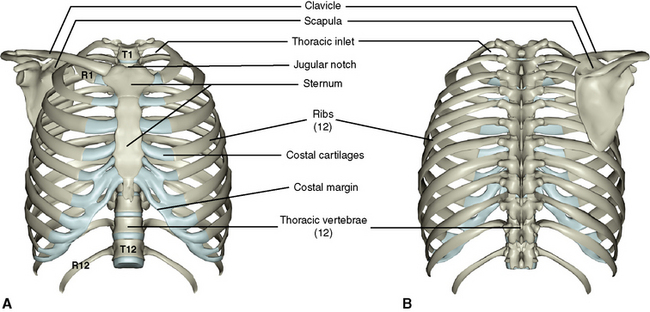

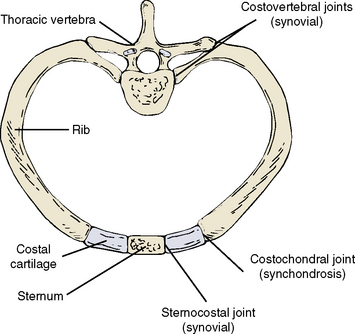

The skeleton of the thorax consists of (1) a midline sternum, (2) 12 pairs of ribs and associated costal cartilages, and (3) 12 thoracic vertebrae (Figure 3-1). The first ribs, sternum, and first thoracic vertebra comprise the thoracic inlet.

Sternum

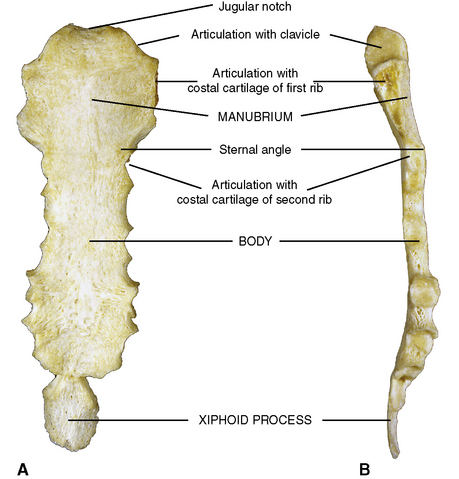

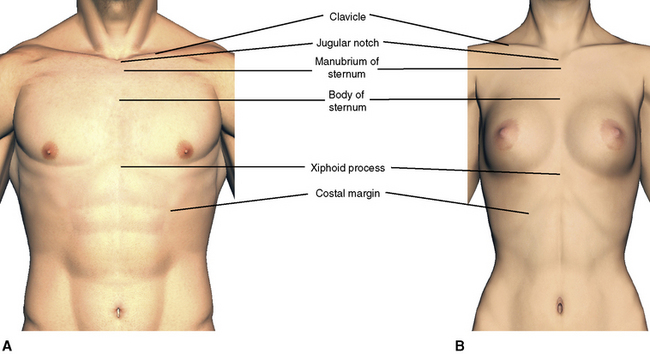

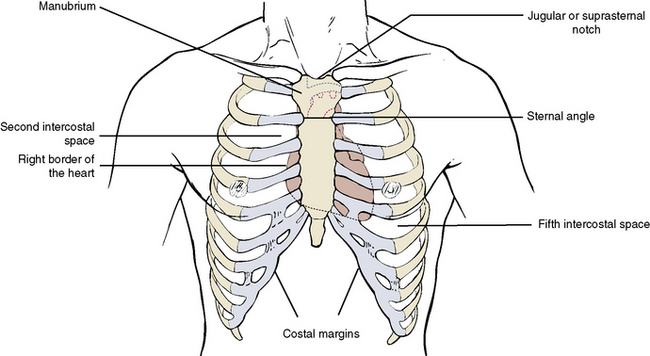

The sternum, or breast bone, consists of three portions: (1) the manubrium; (2) a body, which joins the manubrium as a symphysis at the sternal angle; and (3) the xiphoid process, a small inferior portion (Figure 3-2). Superiorly the manubrium of the sternum presents a midline notch and two lateral notches. The midline notch is the jugular notch, or suprasternal notch, and it can be palpated at the anterior base of the neck. The lateral notches receive the clavicular heads of the upper limb girdle. The extreme lateral borders of the manubrium articulate with the costal cartilages of the first ribs.

Ribs

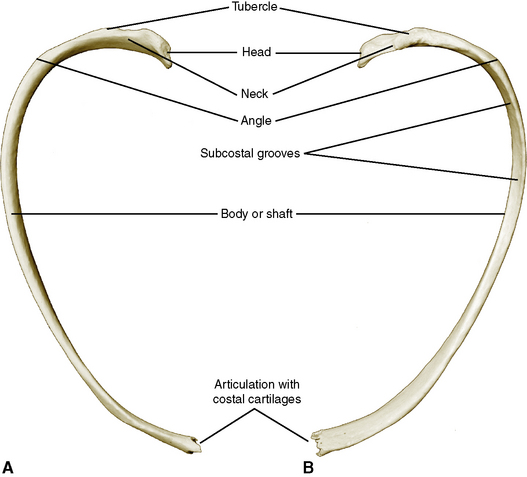

A typical rib consists of (1) a head, which articulates with the body of a thoracic vertebra; (2) a neck; (3) a tubercle, which articulates with the transverse process of a thoracic vertebra; (4) a shaft, or body; (5) an angle, at which the rib turns inferiorly and anteriorly; and (6) a shallow subcostal groove on the internal inferior surface, which shelters the intercostal nerve and vessels (Figure 3-3). Anteriorly the typical rib is joined to the sternum by its own costal cartilage.

There are three types of ribs:

Thoracic Vertebrae

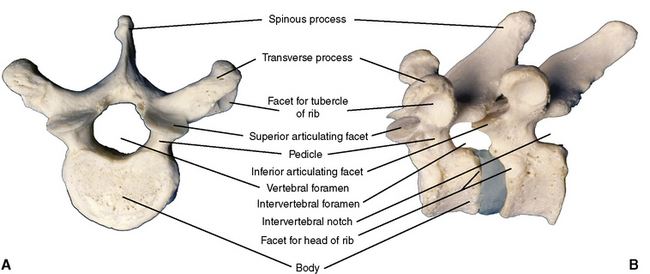

In addition to all of the features attributable to a typical vertebra described in Chapter 2, the thoracic vertebrae exhibit the following unique features: (1) the body is heart-shaped, (2) the spinous processes are long and slender, and (3) the bodies and transverse processes have facets for articulation with ribs (Figures 3-5 and 3-6).

Figure 3-5 A, Superior view of typical thoracic vertebra. B, Left lateral view of two articulated vertebrae.

Figure 3-7 demonstrates the articulation of a rib with a thoracic vertebra. Except for ribs 1, 10, 11, and 12, the head of each rib articulates with the body of its own vertebra and that of the vertebra above. The facets on the vertebral bodies are really demifacets, and in the articulated spine the demifacet below and the one above make a complete facet. Ribs 1, 10, 11, and 12 articulate with only their own vertebrae. The tubercles of the ribs articulate with the transverse processes of each thoracic vertebra.

Joints

The joints between the thoracic vertebrae are considered in Chapter 2. The remaining thoracic joints allow movements that result in expansion of the thoracic cavity during inspiration (see Figure 3-7). The movements of respiration are discussed later in this chapter, under “Mechanics of Breathing.” There are three types of thoracic skeleton joints:

2 The Thoracic or Chest Wall

SURFACE FEATURES

The Breast

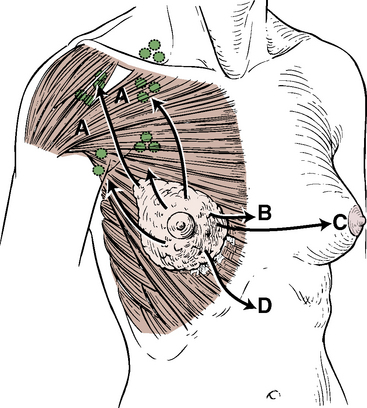

The breast, or mammary gland, arises as modified sweat gland tissue within the superficial fascia of the anterior chest wall and is covered by skin (Figure 3-8). In postpubertal women the breast is a large organ capable of lactation. In men and children it is rudimentary.

Skeletal Landmarks

The following important landmarks in the chest are used to locate underlying structures (Figure 3-9):

MUSCLES

Extrinsic Thoracic Muscles

The superficial muscles covering the chest wall are actually muscles belonging to other regions and are described in sections that discuss these regions. Muscles of the upper limb (see Chapter 9), which originate from the thoracic skeleton, are the pectoralis major and minor, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, rhomboid major and minor, levator scapu-lae, and trapezius. Muscles of the anterior abdominal wall (see Chapter 4), which attach to the thoracic skeleton, are the rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis. Posteriorly, erector spinae and muscles of the back (see Chapter 2) attach to the thoracic skeleton.

Accessory Extrinsic Muscles of Respiration

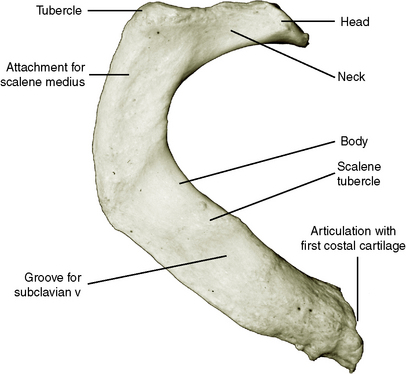

Several muscles of the neck region insert into the skeleton of the upper thorax to elevate the sternum and ribs during forced inspiration. These muscles are the scalenus anterior, scalenus medius, and scalenus posterior and are described fully in Chapter 5, page 151.

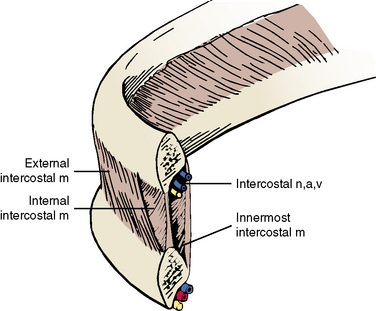

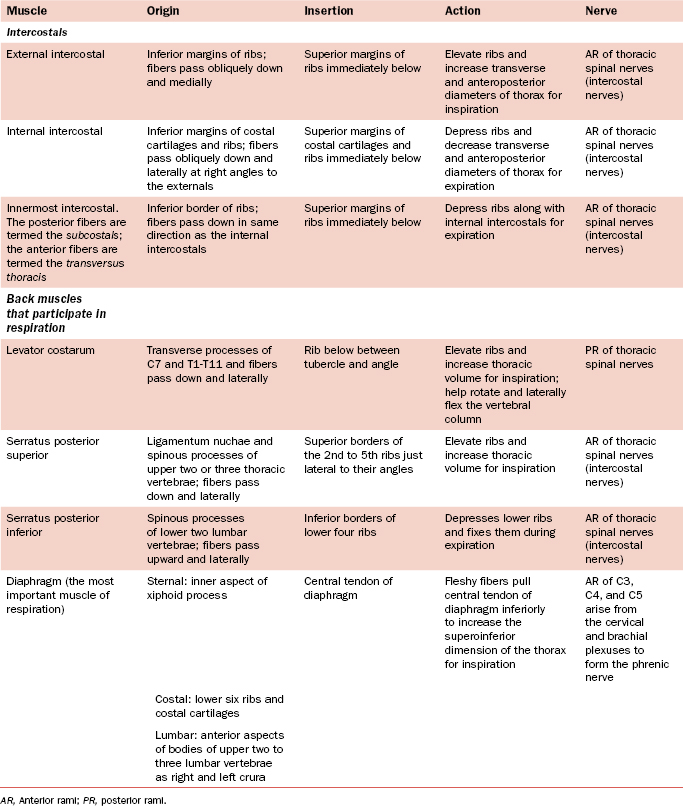

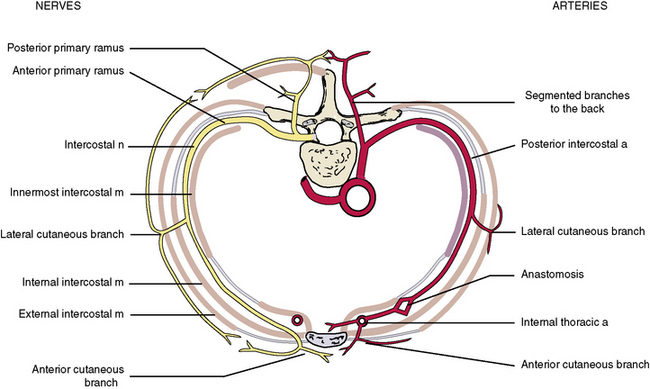

Intercostal Muscles

The intercostal muscles of the thorax are involved with the mechanics of breathing. They run from (1) rib to rib, (2) sternum to rib, and (3) vertebra to rib (Figure 3-10 and Table 3-1). The external intercostal muscles pass from rib to rib in an anteroinferior direction (in the same direction as the external abdominal oblique muscle) and elevate the ribs during inspiration. The internal intercostal muscle passes from rib to rib, perpendicular to the external intercostal muscle, and depresses the ribs during expiration. The innermost intercostal muscles run in same direction as the internal intercostal muscles, but the two layers are separated by the intercostal nerves and vessels. The innermost layer is subdivided into the subcostal and transversus thoracis. They likely aid the internal intercostals in depressing the ribs. Figure 3-11 shows that the muscles are not continuous sheets, and in some areas the muscle is replaced by thin membranous tendon. The intercostal muscles are supplied by intercostal nerves.

Diaphragm

The diaphragm is the most important muscle of respiration and its attachments are described in Chapter 4, pages 96 and 97. On contraction, the diaphragm pulls the central tendon inferiorly to increase the vertical dimension of the thorax during inspiration. It is supplied by the right and left phrenic nerves (anterior rami of C3, C4, and C5).

The serratus posterior superior and inferior are thin, flat muscles on the posterior thoracic wall (see Figure 2-15). The superior muscle runs from the lower cervical and upper thoracic vertebral spines downward and laterally to the upper ribs. It elevates the ribs during inspiration. The inferior muscle arises from the upper lumbar and lower thoracic vertebral spines and passes upward and laterally to insert into the lower ribs. It depresses or stabilizes the lower ribs.

3 The Pleural Cavities and Lungs

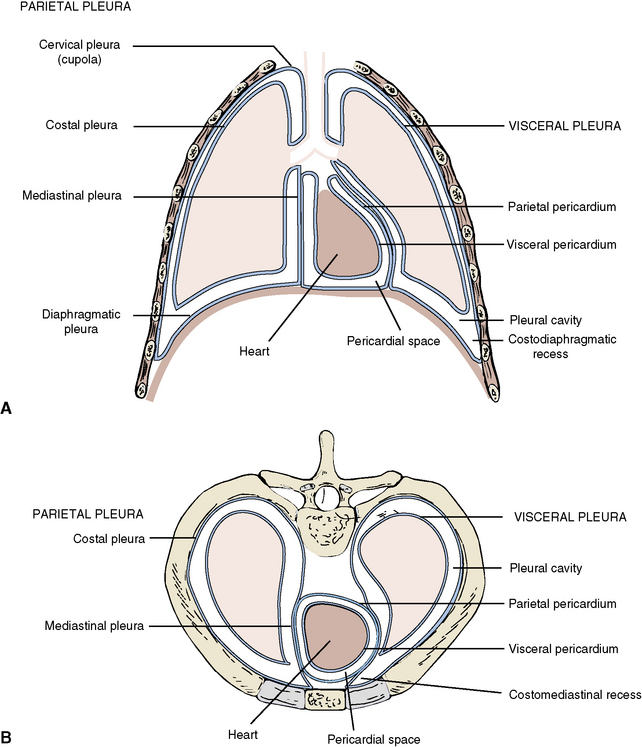

PLEURA

The right and left pleural cavities are completely enclosed spaces within the thorax that contain the right and left lungs (Figure 3-12). Like the peritoneal cavity, the pleural cavity is lined with serous membrane, or pleura.

LUNGS

Surfaces and Borders

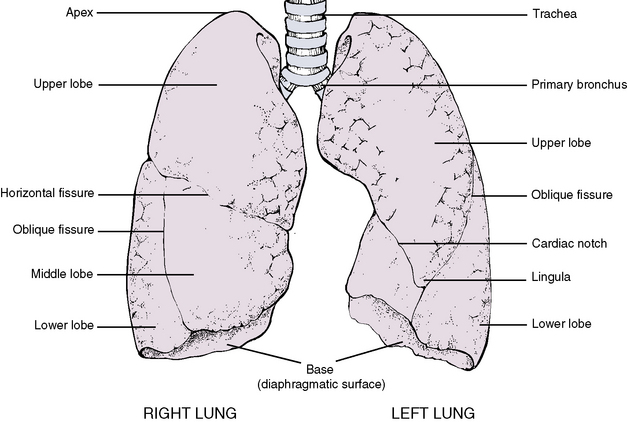

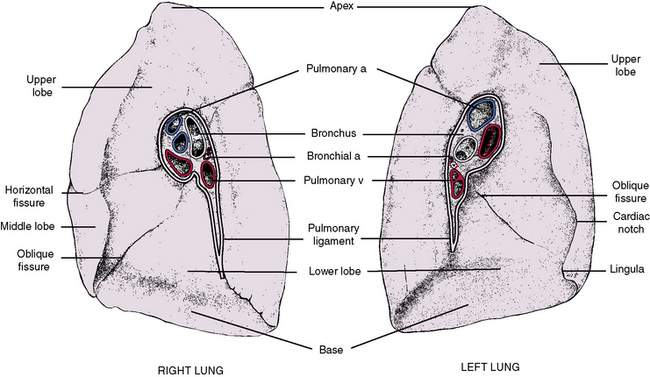

Each lung exhibits four surfaces, each of which takes the shape of surrounding structures (Figures 3-13 and 3-14). The surfaces are (1) the apex, which is a rounded superior aspect that bulges up through the thoracic inlet; (2) the diaphragmatic surface, or base, which rests on the dome of the diaphragm; (3) a mediastinal surface, which contacts the midline mediastinum; and (4) the costal surface, which is rounded to fit the curved ribs.

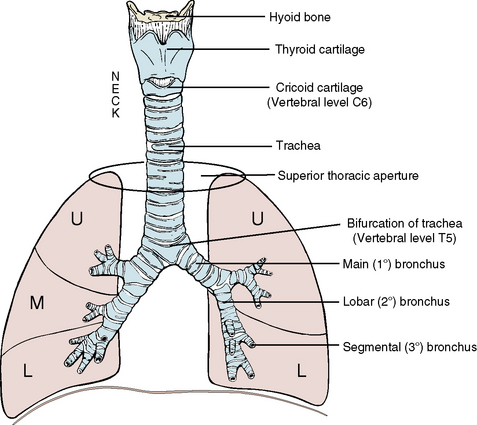

BRONCHI AND BRONCHIAL TREE

The trachea consists of approximately 20 U-shaped, incomplete cartilaginous rings strung together with fibroelastic tissue (Figure 3-15). The posterior deficient portion is covered with fibrous tissue and involuntary muscle. Approximately half the course of the trachea is within the neck. It continues inferiorly from the larynx in the neck, lying anterior to and paralleling the course of the esophagus. Applied laterally to the trachea are the two lobes of the thyroid gland, connected by an isthmus that crosses the second or third tracheal ring (see Chapter 5).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses