3

Periodontics

Few periodontal diseases present problems requiring urgent care. Nevertheless, urgent-care situations do occur and must be addressed quickly and competently. Since such situations are relatively infrequent, the clinician may not be prepared to treat these conditions as readily as those seen more often. This section presents those conditions that manifest as pain or discomfort arising within the periodontium, and the more common urgent-care situations encountered during periodontal therapy.

The goals of treatment of periodontal emergencies are twofold: to alleviate pain and to resolve discomfort. To address these goals adequately, three basic prerequisites to therapy must be satisfied: (1) a thorough medical history must have been obtained, (2) the patient must have provided a complete dental history, and (3) the clinician must have conducted an accurate assessment of the physical status of the patient.

Gingival Abscess

An abscess may be defined as a localized collection of pus in a cavity formed by the disintegration of tissues. The most likely cause of the gingival abscess is the impaction of a small object in the gingival crevice. Some of the most likely offenders are popcorn shells, peanut husks, toothpicks, seeds, toothbrush bristles, or fish bones. The body treats these foreign objects with an acute inflammatory response to isolate or eliminate them. Less frequently, the epithelial surface may have become abraded, and infection with abscess formation occurs secondarily.

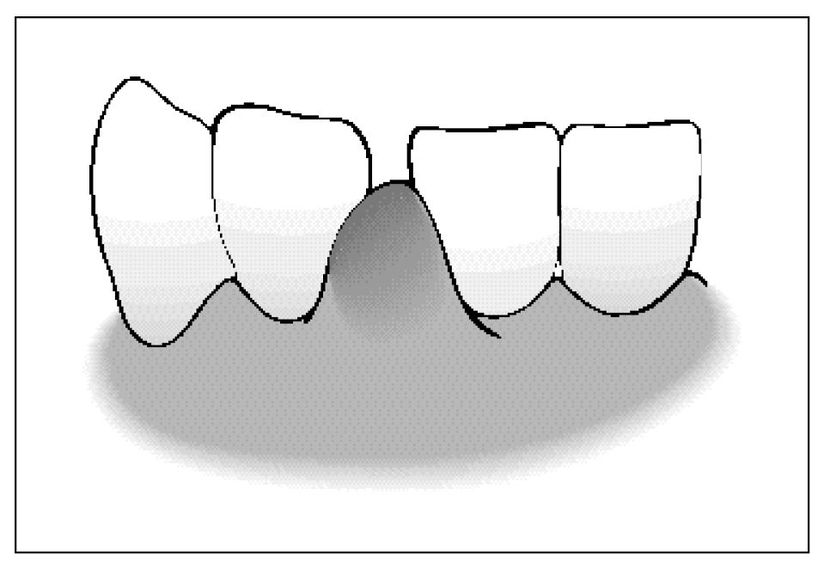

Fig 3-1 Gingival abscess. Note the swelling of the interdental papilla between teeth 25 and 26. Purulent exudate could be expressed with gentle pressure. There were no radiographic changes or loss of clinical attachment.

Fig 3-2 Gingival abscess.

Diagnosis

The gingival abscess appears as a localized, rapidly developing, painful swelling of the marginal or interdental gingiva without evidence of ulceration, desquamation, surface necrosis, or attachment loss. There may be extrusion or tenderness to percussion of the tooth or teeth associated with the abscess, but no radiographic evidence of bone loss. Drainage usually occurs through the gingival crevice, although development of a sinus tract is not uncommon. An example of a typical gingival abscess in the interproximal area of teeth 25 and 26 is presented in Figures 3-1 and 3-2.

Treatment

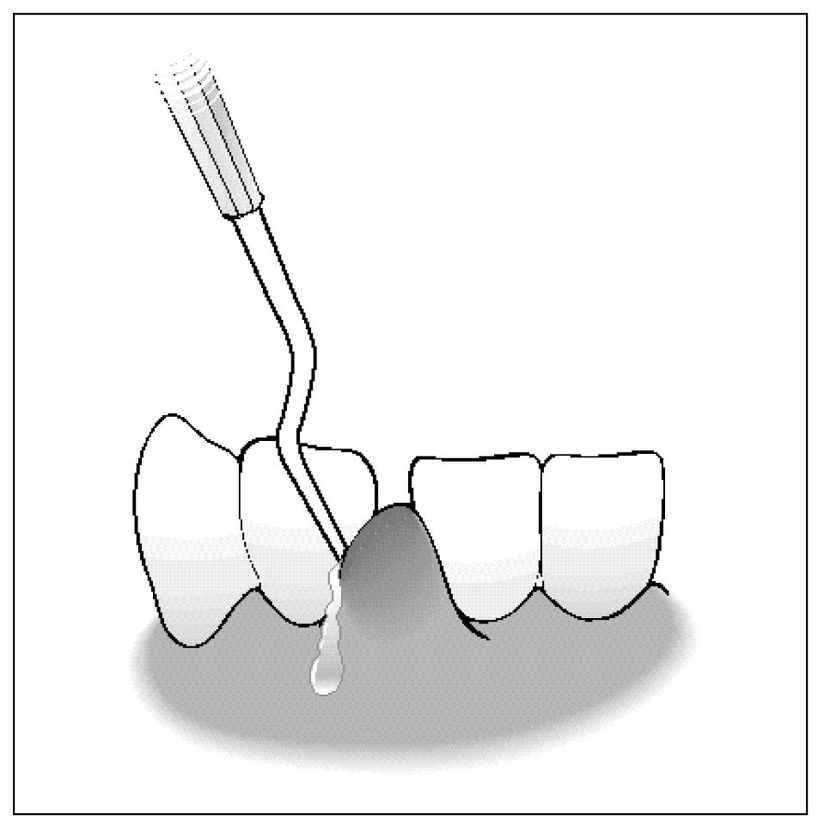

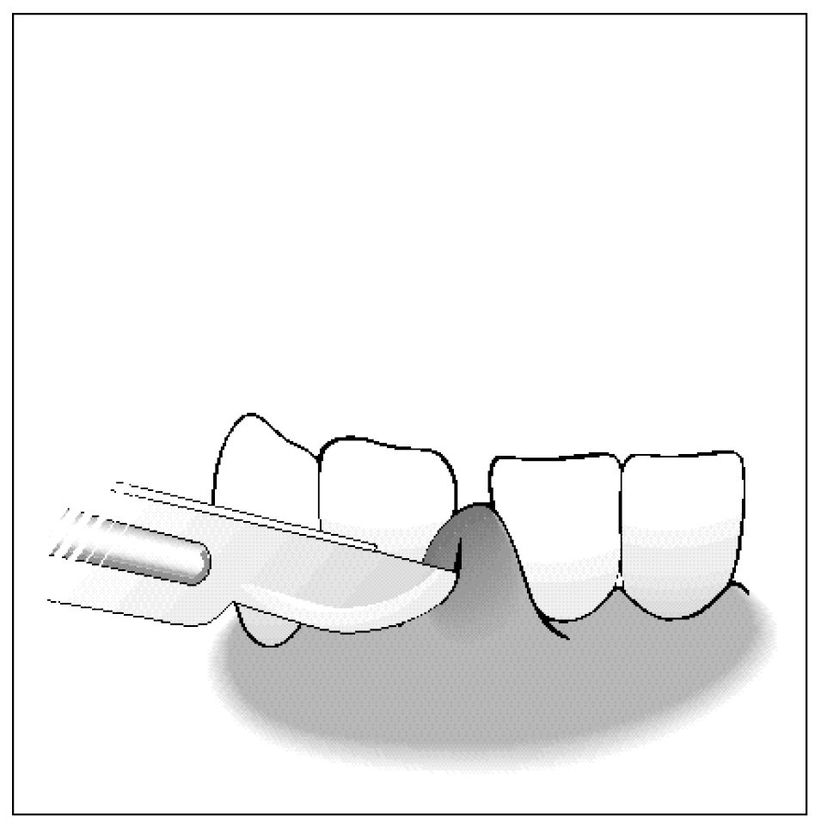

The goals of treatment are to alleviate the symptoms and to identify and eliminate the cause. The following suggested sequence of treatment is also illustrated in Figures 3-3 through 3-4.

| Step 1 | Apply a topical anesthetic (injection anesthesia is rarely needed). |

| Step 2 | Remove the foreign object. Gentle distention of the soft tissue wall of the gingival crevice usually provides sufficient access to the area. Note that the foreign object usually adheres to the soft tissue and rarely to the tooth; consequently, gentle instrumentation should be directed to the soft tissue wall of the lesion to induce drainage. |

| Step 3 | If drainage is not induced spontaneously or in response to gentle curettage, incision and drainage is indicated. Incision and drainage should not be attempted until the foreign object is identified and removed. Care should be taken not to extend the incision to the gingival margin, or permanent recession could result. Regardless of the method used to establish drainage, warm, gentle saline irrigation should follow. The placement of a drain in the incision is usually not required. |

| Step 4 | If hyperocclusion is present and produces more than a slight discomfort, perform a limited occlusal adjustment. Limit the adjustment to that required for pain relief. |

| Step 5 | Advise the patient to use warm saline rinses of 1 to 3 minutes every 1 to 2 hours during waking hours for the following 2 days. |

| Step 6 | Appoint the patient for follow-up in 24 to 48 hours. At that time the pain and swelling should be either greatly reduced or absent, although the site may exhibit slight tenderness to gentle probing. There may be residual fibrosis that could require soft tissue reduction, 30 to 60 days following treatment of the initial lesion, to minimize recurrence. |

| Note: | Antibiotics are rarely needed in treating the gingival abscess unless the patient has systemic symptoms or requires specific antibacterial prophylaxis. |

Fig 3-3 Sulcular drainage is achieved with a periodontal curette, probe, or similar instrument.

Fig 3-4 A surgical knife may be used to establish drainage.

Periodontal Abscess

The etiology of the periodontal abscess involves both microbiologic and local factors. The microorganisms involved are endogenous oral species, but more than two-thirds represent gram-negative anaerobic microorganisms. Local conditions frequently include (1) impaction of material into the orifice of the periodontal pocket, (2) resolution of coronal inflammation, often subsequent to coronal scaling and polishing, resulting in closure or extreme narrowing of the pocket orifice, or (3) improper use of oral irrigating devices (directing the pulsating stream into the pocket rather than at right angles to it).

Diagnosis

All of the classic signs of inflammation, such as swelling, redness, warmth, pain, and loss of function, may be present with the periodontal abscess; however, it is unusual for all these symptoms to be present initially. Those most commonly noted are adenopathy, extrusion of the tooth with resulting mobility, and tenderness on chewing or percussion. The greatest difficulty in determining the presence or absence of periodontal abscess (Fig 3-5) is differentiating it from a periapical abscess (Table 3-1).

Fig 3-5 Periodontal abscess caused be a fingernail sliver that became trapped subgingivally. There was substantial loss of bone in the distal furcation of the first molar and the mesial furcation of the second molar.

Table 3-1 Symptoms Associated with Periapical and Periodontal Abscesses

| Symptom | Periapical Abscess | Periodontal Abscess |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Acute, severe, difficult to control with analgesics | Acute or chronic, mild to moderate, usually controlled with analgesics |

| Swelling | Present in mucobuccal fold, spreads following facial planes | Present in gingiva, rarely spreads beyond the mucogingival junction |

| Probing | If draining through the periodontal ligament space, the opening is small. If a sinus tract forms, it is usually located apical to the mucogingival junction. | Opening into the periodontal pocket is wider than that for periapical lesions, but may be masked by narrow, tortuous pockets. Sinus tracts are frequently located in the gingiva or at the mucogingival junction. |

| Radiographs | Bone loss around a single tooth in a periodontally healthy individual suggests periapical disease. Bone loss at the apex suggests periapical disease, but could be periodontal disease. | Bone loss lateral to the tooth suggests periodontal disease, but the presence of lateral canals could allow pulpal disease to mimic the appearance of the periodontal abscess. |

| Tests (after acute phase is treated) | Negative responses to pulp vitality tests strongly suggest periapical disease. | Positive responses to pulp vitality tests strongly suggest that the problem is of periodontal origin. |

Treatment

Treatment of the periodontal abscess must address both components of the etiology, that is, the microbiologic as well as the local factors. The goals are to alleviate the acute phase and convert it into a chronic lesion to establish a definitive diagnosis, and to correct any defect resulting from the lesion. The following suggested sequence of treatment is also illustrated in Figures 3-6, 3-7, 3-8, 3-9.

| Step 1 | Obtain anesthesia through the use of either infiltration or block methods. (Infiltration anesthesia may have only limited effectiveness depending on the intensity and extent of the acute inflammatory infiltrate.) |

| Step 2 | Establish drainage. |

| The first attempt should be through the pocket and may require no more than the careful use of a periodontal probe to explore the extent of a pocket. Once the opening to the abscess is located, the root surface is debrided, starting with the use of small curettes and progressing to the use of larger instruments. | |

| If drainage cannot be established through the orifice of the pocket, incision should be considered. A vertical incision is usually used with attempts to avoid extension to the gingival margin. If the incision must extend to the gingival margin, this should occur in the interproximal area to avoid posttreatment recession. | |

| Step 3 | Irrigate the abscess lumen thoroughly with a warm saline solution. |

| Step 4 | If an incision was necessary, placement of a drain in the incision will allow further resolution of the lesion and prevent premature closure of the incision. |

| Step 5 | If hyperocclusion is present and produces more than a slight discomfort, perform a limited occlusal adjustment. Limit the adjustment to that required for pain relief. |

| Step 6 | Advise the patient to continue with warm saline rinses every 1 to 2 hours during waking hours for the following 24 to 48 hours. |

| Step 7 | Appoint the patient for follow-up in 24 to 48 hours. At that time the pain and swelling should be either greatly reduced or absent, although the site may exhibit slight tenderness to gentle probing. If a definitive diagnosis of periapical or periodontal abscess could not be determined initially, pulp vitality can be more accurately determined at this time and definitive treatment can proceed accordingly. |

| Step 8 | Schedule the patient for surgery within 1 to 2 weeks to gain access to the root surface for thorough debridement. Only surfaces with calcified deposits should receive root planing since other areas exposed by the abscess have a high potential for periodontal ligament reattachment. Bone removal is contraindicated during this procedure because periodontal regeneration can be expected to occur in the area where attachment loss occurred during the acute phase. |

| Note: | Antibiotics should be prescribed if the patient is febrile, has moderate to severe lymphadenopathy, is debilitated, or has some underlying systemic disease. As noted above, the primary microorganisms associated with the periodontal abscess are gram-negative anaerobic microorganisms. The antibiotic should be selected accordingly (Table 3-2). |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses