Impairment and disability

The International Classification (ICIDH) system, distinguishes impairment (I) from disability (D) and handicap (H; Table 28.1). Terminology related to disability varies in different countries. For example, the term ‘mental retardation’, as used in the USA, is not used in UK, where ‘learning disability’ and ‘learning, intellectual or cognitive impairment’ are accepted terms. The UK Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA) considers a person as disabled if they have a mental or physical impairment that interferes with their ability to carry out everyday activities. Barriers that can create disability from impairment are shown in Table 28.2. The DDA, the Americans with Disabilities Act 1990 and similar acts in other developed countries make it unlawful to treat disabled people less favourably for reasons related to their disability, and thus service providers need to ensure that the physical features of their premises overcome any barriers to access.

Table 28.1

International Classification system

| Term | Definition |

| Impairment | The functional limitation caused by physical, mental or sensory impairment (i.e. it is organ-based) |

| Disability | The loss or limitations of opportunities to participate in the normal life of the community on an equal level with others, due to physical or social barriers (i.e. it is person-based) |

| Handicap | The disadvantage suffered as a consequence of impairment and disability (i.e. it is socially based) |

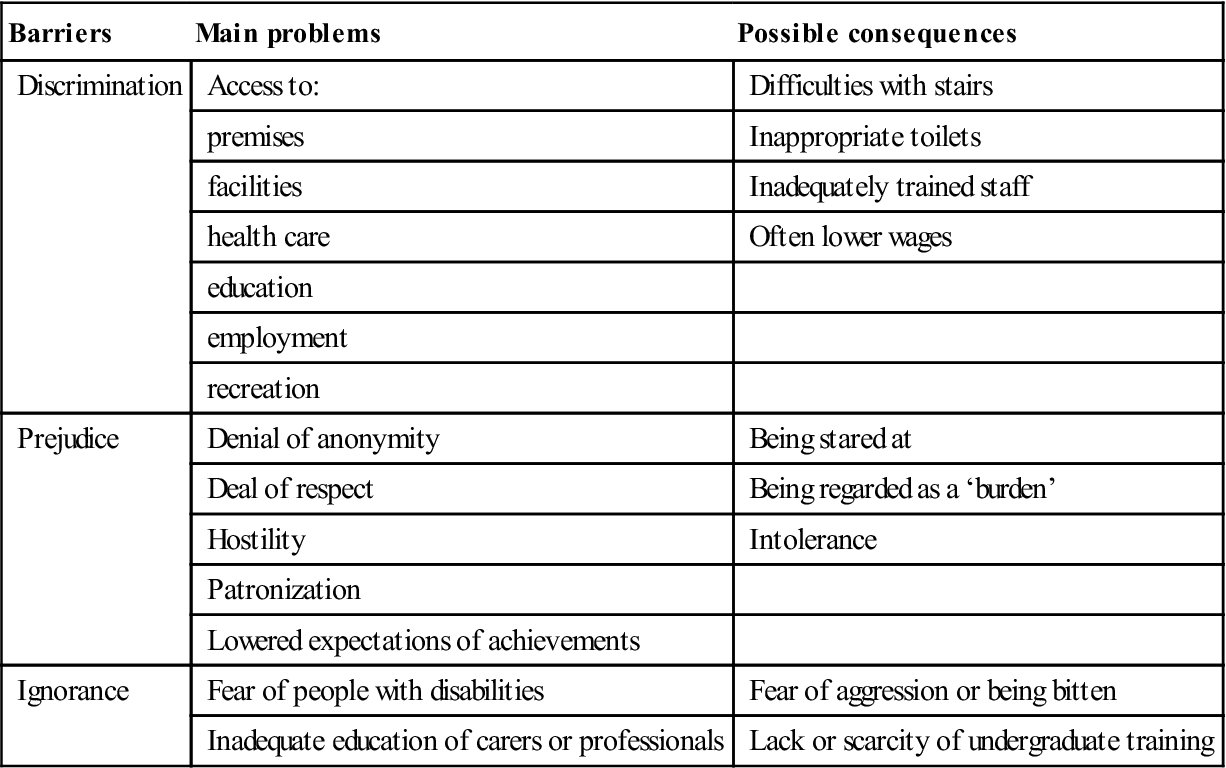

Table 28.2

Barriers that can create disability from impairmenta

< ?comst?>

| Barriers | Main problems | Possible consequences |

| Discrimination | Access to: | Difficulties with stairs |

| premises | Inappropriate toilets | |

| facilities | Inadequately trained staff | |

| health care | Often lower wages | |

| education | ||

| employment | ||

| recreation | ||

| Prejudice | Denial of anonymity | Being stared at |

| Deal of respect | Being regarded as a ‘burden’ | |

| Hostility | Intolerance | |

| Patronization | ||

| Lowered expectations of achievements | ||

| Ignorance | Fear of people with disabilities | Fear of aggression or being bitten |

| Inadequate education of carers or professionals | Lack or scarcity of undergraduate training |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

The main conditions causing disability are shown in Table 28.3. Only patients with physical or mental impairment and some specific conditions will be considered here. Patients with other important specific diseases that can prove disabling, such as haemophilia, neurological disorders and muscular dystrophies, as well as children and older people, are discussed in other chapters.

Table 28.3

Important conditions with impairments

| Mental impairment | Visual defects and hearing defects | Physical disorders |

| Autism disorders | Various | Cardiac disease |

| Chromosomal anomalies, especially Down syndrome | Cerebral palsy | |

| Dyslexia | Cleft deformities | |

| Learning impairments | Cystic fibrosis | |

| Hydrocephalus | ||

| Juvenile arthritis | ||

| Muscle diseases | ||

| Spinal cord damage (especially paraplegia) and spina bifida | ||

| Thalidomide deformities |

Physical Impairments

General aspects and clinical features

Physical disabilities include orthopaedic, neuromuscular, cardiovascular and pulmonary disorders. The disability may be either congenital or acquired – typically the result of injury or disease. People with disabilities often rely for mobility upon devices such as wheelchairs, crutches, frames (e.g. Zimmer), walking sticks and artificial limbs. Some people may have additional hidden (non-visible) disabilities, which include epilepsy or respiratory and other disorders.

General management

Limited access to transport and buildings or reluctance of staff to provide care are the major barriers to health care. Decreased physical stamina and endurance, impaired eye–hand coordination or impaired verbal communication may complicate care.

Accept the fact that a disability exists and approach the patient with sensitivity (Box 28.1). When it appears that a person needs assistance, ask if help can be given. Assistance, if requested, should be provided. If a person’s speech is difficult to understand, do not hesitate to ask them to repeat. Sensitivity to using words like ‘walking’ or ‘running’ is inappropriate; people who are handicapped use such words. Always ask first while facing a person who uses a wheelchair; never come up from behind and push them. Try to have conversations at the same eye level by sitting, kneeling or squatting where appropriate. However, a wheelchair is part of the person’s body space, so do not hang or lean on it.

Some who have to use wheelchairs can achieve amazing feats, such as in the Para-Olympic Games (Fig. 28.1), and can walk with the aid of canes, braces, crutches or walkers. Others cope with extraordinary impairments and perform amazing feats.

Dental aspects

Guidelines for care are available at http://www.bsdh.org.uk/guidelines/physical.pdf (accessed 30 September 2013).

Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common congenital physical handicap. It is caused by brain damage early in development, either during fetal life, during the birth process or during the first few months of infancy. Brain damage is caused mainly by hypoxia, trauma, infection or hyperbilirubinaemia, but genetic or other biochemical factors may be involved. Risk factors are shown in Box 28.2.

Clinical features

People with CP have abnormalities of motor control that can cause abnormalities of movement and posture in various parts of the body. CP shows no uniform pattern because of the many variations in brain damage (Table 28.4), but features may include delays in motor skills development, poor control over hand and arm movement, weakness, abnormal walking with one foot or leg dragging, and excessive drooling or difficulties in swallowing. Many patients are highly intelligent but may have such severely impaired speech as to appear to have learning impairment. Up to 50% do have additional challenges, such as epilepsy, defects of hearing, vision or speech, learning impairment or emotional disturbances.

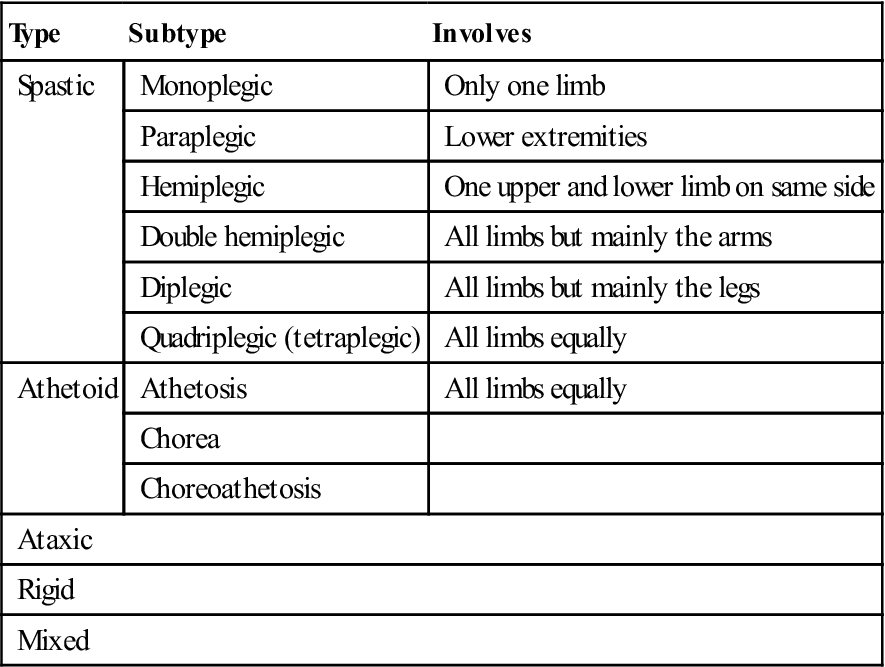

Table 28.4

< ?comst?>

| Type | Subtype | Involves |

| Spastic | Monoplegic | Only one limb |

| Paraplegic | Lower extremities | |

| Hemiplegic | One upper and lower limb on same side | |

| Double hemiplegic | All limbs but mainly the arms | |

| Diplegic | All limbs but mainly the legs | |

| Quadriplegic (tetraplegic) | All limbs equally | |

| Athetoid | Athetosis | All limbs equally |

| Chorea | ||

| Choreoathetosis | ||

| Ataxic | ||

| Rigid | ||

| Mixed | ||

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Spastic cerebral palsy is the most common type, and CP patients were sometimes loosely referred to as ‘spastics’. It is an upper motor neuron lesion that manifests with excessive muscle tone and contractures, pathological reflexes and hyperactive tendon reflexes (Fig. 28.2). Many people with CP may need to use wheelchairs (Fig. 28.3). Hemiplegia is a common subtype, often associated with neurological disorders such as epilepsy, or sensory or visual field defects. Quadriplegics may more frequently have learning impairment but are less often epileptic. Paraplegics and diplegics have an intelligence quotient (IQ) intermediate in level between quadriplegics and hemiplegics, but are the least likely to have epilepsy.

Athetoid cerebral palsy accounts for 15% of CP. It is caused by extrapyramidal damage, usually in the basal ganglia, giving rise to smooth worm-like movements that become exaggerated under stress. There is excessive muscle tone of the ‘lead-pipe’ type: the limb, when flexed, moves like a lead pipe that is being bent, but there are normal tendon reflexes and no contractures. Athetoid CP is mainly caused by intrauterine rubella and by hyperbilirubinaemia (kernicterus as in rhesus incompatibility). It usually involves the arms especially but all four limbs are affected; it is often accompanied by high-tone deafness. Epilepsy can be associated but learning impairment is less common than in spastic CP.

Ataxic cerebral palsy, caused by a cerebellar lesion, accounts for about 10% of all CP, and is characterized by disturbed balance.

General management

CP brain damage is unfortunately irreversible, but muscle training and exercises help the child’s strength, balance and mobility, and increase independence. Muscle relaxants ease stiffness and anticonvulsants reduce seizures. Support from occupational therapists, speech therapists, audiologists, ophthalmic specialists, orthopaedic specialists and dieticians is invaluable.

Dental aspects

Patients restricted to wheelchairs can sometimes be treated in their wheelchair or using a double-articulating headrest, but otherwise it is often better to transfer them to the dental chair by carrying them, using a hoist or sliding them across a ‘banana’ transfer board placed between the wheelchair and dental chair, or to tilt their wheelchair. Ataxic and some other patients may need the wheelchair to be tilted backwards. Many, however, become apprehensive when this is done. If not, some clinics provide a wheelchair-tilting device such as Versatilt®, Safari® or Diaco®.

Uncontrollable movements, especially in athetosis, bruxism, abnormal attrition and spontaneous dislocation or subluxation of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), are common.

Communication difficulties, along with concentration, which is often poor, may give a misleading impression of low intelligence. Epilepsy may be seen. Abnormal swallowing and drooling are common due to poor control of the oral tissues and head posture. Anxiety may worsen athetosis or spasticity, so that anxiolytic drugs such as diazepam are useful as pre-medication.

Preventive dental care is important. Parental counselling about diet, oral hygiene procedures and the use of fluorides should be started early. Manual dexterity is usually poor but favourable results are often achievable with an electric toothbrush or a modified handle on a normal brush. Most dental disease is more common when the arms are severely affected. Periodontal disease is frequently found, especially in the older child, because soft-tissue movement is abnormal and oral cleansing is impaired. Mouth-breathing worsens the periodontal state, and papillary hyperplastic gingivitis may be seen, even in the absence of treatment with phenytoin.

There may be delayed eruption of the primary dentition and enamel hypoplasia is common. Caries activity appears normal, unless there is overindulgence by carers or others, but lack of treatment frequently leads to premature loss of primary teeth and earlier eruption of premolars and permanent canines. Malocclusion is common, probably caused by abnormal muscle behaviour. The maxillary arch is frequently tapered or ovoid, with a high palate. The upper teeth are often labially inclined, due to the pressure of the tongue against the anterior teeth during abnormal swallowing. Most, however, have skeletal patterns within normal limits.

Cleft Lip and Palate

See Chapter 14.

Hydrocephalus

General aspects

Hydrocephalus (hydro from the Greek for water and cephalus from the Greek for head) is a neurological disorder that affects approximately 1 in 1000 children. It is caused by raised intracranial pressure (ICP), usually due to an abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the ventricles and/or subarachnoid space. CSF is overproduced, its flow is obstructed, or there is a failure to reabsorb it. In normal pressure hydrocephalus, the ventricles are enlarged but there is little or no rise in ICP.

Hydrocephalus is considered congenital when X-linked, or its origin can be traced to a birth defect or brain malformation that impairs drainage of CSF. Congenital hydrocephalus can be caused by TORCH syndrome from intrauterine infection, usually with toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus or herpes. Congenital hydrocephalus may be seen in spina bifida with myelomeningocoele, or as a part of other neurological conditions and congenital malformations (e.g. Dandy–Walker syndrome, neural tube defects, Chiari malformations, vein of Galen malformations, craniosynostosis, schizencephaly and tracheo-oesophageal fistula).

Hydrocephalus can be acquired later in life if there is a rise in resistance to CSF drainage, such as by obstruction from a brain tumour, arachnoid cyst, intracranial or intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), trauma, or infection such as meningitis.

The term ‘communicating hydrocephalus’ means that the site of raised resistance to CSF drainage is outside the ventricular system in the subarachnoid space. Non-communicating, or obstructive, hydrocephalus is caused by a CSF obstruction within the ventricular system, especially in the aqueduct of Sylvius, at outlets of the fourth ventricle (foramina of Luschke and Magendie) or from the lateral ventricles into the third ventricle at the foramina of Monro.

Clinical features

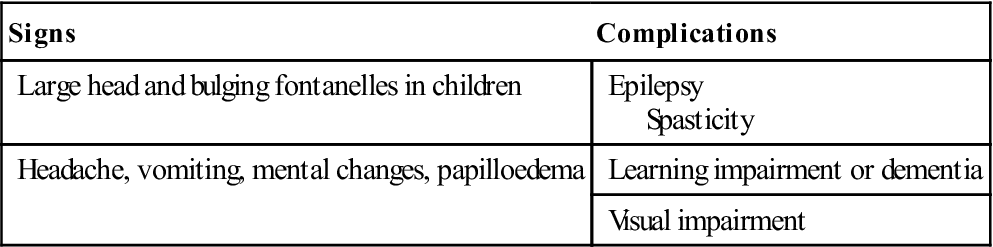

The main features of hydrocephalus are outlined in Table 28.5.

Table 28.5

< ?comst?>

| Signs | Complications |

| Large head and bulging fontanelles in children | Epilepsy Spasticity |

| Headache, vomiting, mental changes, papilloedema | Learning impairment or dementia |

| Visual impairment |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

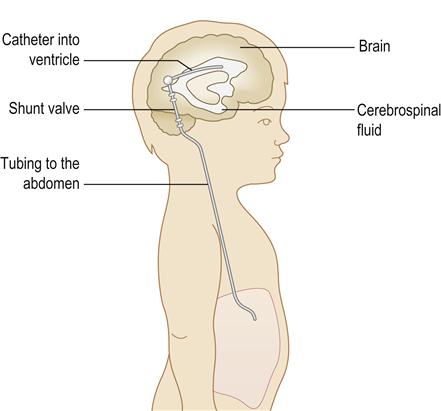

General management

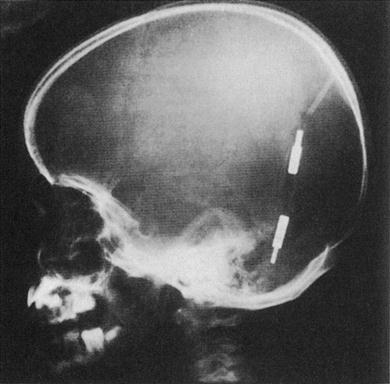

Hydrocephalus can be treated directly, by removing the cause of CSF obstruction or overproduction, or indirectly, by diverting the CSF build-up to somewhere else. Diuretics (acetazolamide and furosemide) may help reduce CSF production. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) may relieve CSF pressure. However, in many cases, CSF has to be redirected. Initially, such ‘shunts’ were into the right atrium (Spitz–Holter shunt, ventriculo-atrial [VA] shunt; Fig. 28.4) but now they are typically into another body cavity (usually the peritoneal cavity – ventriculo-peritoneal [VP] shunt) via an implanted silastic device (Fig. 28.5). Shunt-lengthening surgery may be needed as the child grows.

Dental aspects

The weight of the hydrocephalic head may cause difficulties, especially in the anaesthetized patient, and there may be other management challenges, including shunt infection, or frequently associated spina bifida, latex allergy, epilepsy, or learning or visual impairment.

The consequences of infection can be so devastating that antibiotic cover may occasionally need to be given before oral procedures that might produce bacteraemia in patients with a VA shunt. There is probably no indication for antimicrobial prophylaxis for patients with a VP shunt. The risk of CSF shunt infection following dental procedures appears to be almost negligible and there are no reported cases. There is no evidence that Streptococcus viridans isolated from CSF shunt infections has been of oral origin (https://www.evidence.nhs.uk – search on ‘hydrocephalus shunts and antibiotic prophylaxis’; accessed 30 September 2013).

Spina Bifida

General aspects

Spina bifida is failure of fusion of the vertebral arches; it is an important cause of spinal cord disease and severe physical handicap. Deficiency of folic acid in pregnancy may predispose but most cases are of unknown aetiology.

Clinical features

There is a range of impairments in spina bifida (Table 28.6) but patients with myelomeningocoele are most severely handicapped and tend to suffer from an inability to walk, liability to develop pressure sores, urinary incontinence, faecal retention and other problems, such as hydrocephalus, epilepsy or learning impairment, and other vertebral or renal anomalies.

Table 28.6

| Type | Features |

| Spina bifida occulta | Rarely any obvious clinical or neurological disorder but may be detected by a small naevus or tuft of hair over the lumbar spine in some patients, and radiographi/> |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses