Malignant Diseases

Disease Mechanism

Malignant tumors represent an uncontrolled growth of tissue. In contrast to benign neoplasms, they are more locally invasive, have a greater degree of cellular anaplasia, and have the ability to metastasize regionally to lymph nodes or distantly to other sites. Malignant tumors that arise de novo are termed primary tumors, and a lesion that originates from a distant primary tumor is termed a secondary or metastatic malignancy. Cancers may be caused by viruses, significant radiation exposure, genetic defects, or exposure to carcinogenic chemicals. For instance, using tobacco is strongly associated with oral carcinoma.

The most convenient method of classification of cancers is based on histopathology. In this chapter, malignancies that commonly affect the jaws have been divided into four categories: (1) carcinomas (lesions of epithelial origin), (2) metastatic lesions from distant sites, (3) sarcomas (lesions of mesenchymal origin), and (4) malignancies of the hematopoietic system. Of these four categories, carcinomas are by far the most commonly encountered in dental practice. The prognosis for the patient is related to early detection. Often, malignant lesions are not recognized and are treated inappropriately as inflammatory disease. Discussion of unusual malignant tumors has been omitted from this chapter to concentrate on more common lesions that a general practitioner may encounter.

Clinical Features

Clinical signs and symptoms that suggest a lesion may be malignant include the following: displaced teeth, loosened teeth over a short time, foul smell, ulceration, presence of an indurated or rolled border, exposure of underlying bone, sensorineural or sensorimotor deficits, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, dysgeusia, dysphagia, dysphonia, hemorrhage, lack of normal healing after oral surgery, and pain or rapid swelling with no demonstrable dental cause. Most oral cancers occur in men 50 years old and older; however, malignant tumors may occur at any age in either gender.

Dentists must watch vigilantly for the possibility of malignancy in their patients. Because the prevalence of oral malignancy is low, many general dentists practice years without encountering a patient with a malignant tumor. This rarity may make a dentist less likely to recognize a malignant condition when it is present. The risks of lack of attention to this possibility are delayed diagnosis, delayed treatment, increased need for aggressive treatment with added morbidity, and, in the worst case, premature death.

Applied Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic imaging has many important roles in the management of a patient with cancer. First, images may aid in the establishment of an initial diagnosis of a tumor. Diagnostic imaging also aids in the appropriate staging of disease from early small cancers to large cancers that have spread. Appropriate radiologic investigations assist the surgeon or radiation oncologist to determine the anatomic spread of the tumor so that it can be excised or irradiated adequately. Radiologic investigation can determine the presence of osseous involvement from soft tissue tumors, help to determine good biopsy sites, and allow the practitioner to assess the involvement of lymph nodes and treatment outcome. Finally, a thorough diagnostic imaging examination is part of the management of a patient who has survived cancer, who often is rendered xerostomic; neutropenic; and susceptible to dental caries, periodontal disease, and systemic infection.

Various diagnostic imaging modalities are available to aid in the diagnosis. Intraoral images provide the best image resolution and reveal subtle malignant changes, such as irregular widening of the periodontal membrane space. Panoramic images provide an overall assessment of the maxillofacial osseous structures and can reveal relevant changes, such as destruction of the boundaries of the maxillary sinus. Either cone-beam computed tomographic (CBCT) or multidetector CT (MDCT) images can provide a superior three-dimensional analysis of the osseous structures and better determine the position and extent of the tumor. Positron emission tomographic (PET) imaging, a technique capable of detecting abnormal cellular metabolic activity associated with malignant tumors, has been fused with MDCT imaging to provide an accurate location of the tumor in preparation for radiotherapy. Finally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has provided three-dimensional soft tissue images of tumors and information regarding perineural spread and involvement of lymph nodes.

Imaging Features

The following features may suggest the presence of a malignant tumor. The absence of visible radiologic signs as described does not preclude malignancy. It implies only that no visible imaging signs exist.

Location

Primary and metastatic malignant tumors may occur anywhere in the oral and maxillofacial region. Primary carcinomas are more commonly seen in the tongue, floor of the mouth, tonsillar area, lip, soft palate, or gingiva and may invade the jaws from any of these sites. Sarcomas are more common in the mandible and in posterior regions of both jaws. Metastatic tumors are most common in the posterior mandible and maxilla. Some metastatic lesions grow at the apices of teeth or in the follicles of developing teeth (see Fig. 24-1, D).

Periphery and Shape

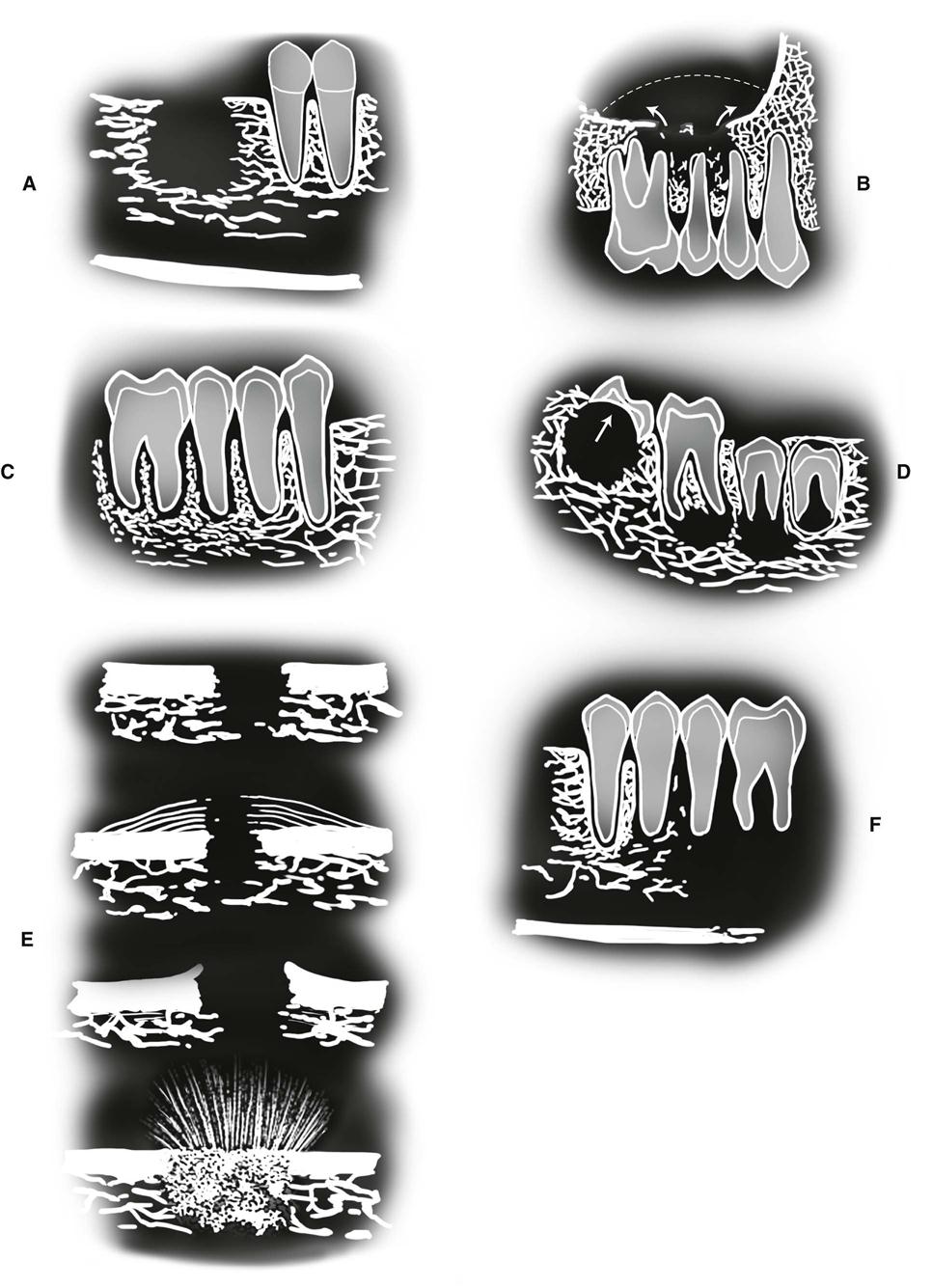

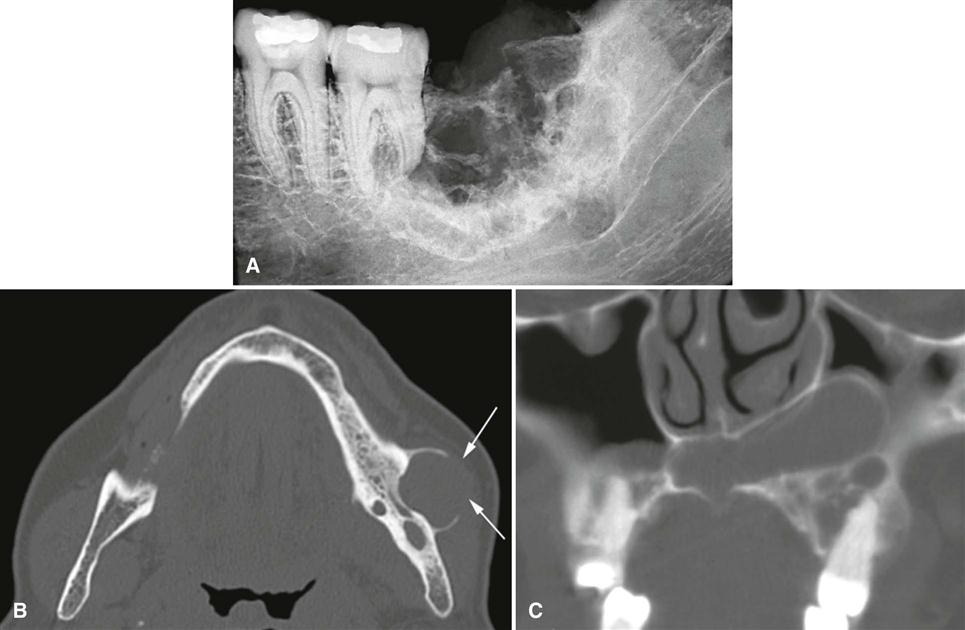

The typical appearance of the periphery (border) of a malignant lesion is an ill-defined border with lack of cortication and absence of encapsulation (a soft tissue or radiolucent periphery). This border usually extends from an area of bone destruction (radiolucent) to a region of normal bone with uneven extensions and is referred to as an infiltrating pattern (Fig. 24-1, A). This border is produced by finger-like extension of the tumor in many directions. In contrast, some malignancies, especially squamous carcinomas arising in adjacent soft tissues and invading the mandible, may have well-defined borders. Evidence of destruction of a cortical boundary with adjacent soft tissue mass is highly suggestive of malignancy (Fig. 24-1, B). Such a mass may exhibit a smooth or ulcerated peripheral border if cast against a radiolucent background, such as the air within the maxillary sinus. The shape of a malignant tumor of the jaw is commonly irregular.

Internal Structure

Because most malignancies do not produce bone and do not stimulate the formation of reactive bone, the internal aspect is typically radiolucent in most instances. Occasionally, residual islands of bone are present, resulting in a pattern of patchy destruction with some scattered residual internal osseous structure. Some tumors, such as metastatic prostate or breast lesions, can induce bone formation, resulting in an abnormal-appearing internal sclerotic osseous architecture, whereas others, such as osteogenic sarcomas, can produce abnormal bone giving the involved bone a sclerotic (radiopaque) appearance.

Effects on Surrounding Structures

Malignancy is destructive, often rapidly so. The effect on surrounding structures mirrors this behavior. Slower growing benign tumors or cysts may resorb tooth roots or displace teeth in a bodily fashion without causing loose teeth. In contrast, rapidly growing malignant lesions generally destroy supporting alveolar bone so that teeth may appear to be floating in space (see Fig. 24-1, F).

Occasionally, root resorption is present; this is more common in sarcomas and multiple myeloma. Internal trabecular bone is destroyed, as are cortical boundaries such as the sinus floor (see Fig. 24-1, B), inferior border of the mandible, follicular cortices of developing teeth, and cortex of the inferior alveolar neurovascular canal. Because malignant tumors tend to grow rapidly, they invade via the easiest routes, such as through the maxillary antrum or through the periodontal ligament space around teeth, resulting in irregular widening with destruction of the lamina dura (Fig. 24-1, C); they also may spread through the inferior alveolar neurovascular canal, causing similar widening. Usually no periosteal reaction occurs where the tumor has destroyed the outer cortex of bone; however, some tumors stimulate unusual periosteal new bone formation (see Fig. 24-1, E). Lesions such as osteosarcoma and metastatic prostate lesions as well as other tumors can stimulate the formation of thin straight spicules of bone, giving a “hair-on-end” or “sunburst” appearance. If there is a secondary inflammatory lesion coexisting with the malignancy, a periosteal reaction normally associated with an inflammatory lesion (e.g. onion skin–like) may be seen.

Carcinomas

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising in Soft Tissue

Synonym

Epidermoid carcinoma is a synonym for squamous cell carcinoma arising in soft tissue.

Disease Mechanism

Squamous cell carcinoma, the most common oral malignancy, may be defined as a malignant tumor originating from surface epithelium. The etiology appears to be multifactorial with chronic smoking and alcohol use implicated as risk factors. Mucosal human papillomaviruses have been implicated in playing a role in some tonsillar and tongue lesions. Histologically, squamous cell carcinoma is characterized initially by invasion of malignant epithelial cells into the underlying connective tissue with subsequent spread into deeper soft tissues and occasionally into adjacent bone; regional lymph nodes; and ultimately distant sites, such as the lung, liver, and skeleton.

Clinical Features

Squamous cell carcinoma appears initially as white or red (sometimes mixed), irregular patchy lesions of the affected epithelium. With time, these lesions exhibit central ulceration; a rolled or indurated border, which represents invasion of malignant cells; and palpable infiltration into adjacent muscle or bone. Pain may be variable, and regional lymphadenopathy with hard lymph nodes that may or may not be tethered to underlying structures may be present. Other clinical features include a soft tissue mass, paresthesia, anesthesia, dysesthesia, pain, foul smell, trismus, grossly loosened teeth, or hemorrhage. Large lesions can obstruct the airway, the opening of the eustachian tube (leading to diminished hearing), or the nasopharynx. Patients often report significant weight loss and feel unwell. Males are more commonly affected than females. The condition is often fatal if untreated. Most squamous cell carcinomas occur in persons older than 50 years.

Imaging Features

Location.

Squamous cell carcinoma commonly involves the lateral border of the tongue. A common site to observe bone invasion is the posterior lingual aspect of the mandible. Lesions of the lip and floor of the mouth may similarly invade the anterior mandible. Lesions involving attached gingiva and underlying alveolar bone may mimic inflammatory disease, such as periodontal disease. This malignancy is also seen on the tonsils, soft palate, and buccal vestibule. It is uncommon on the hard palate.

Periphery and Shape.

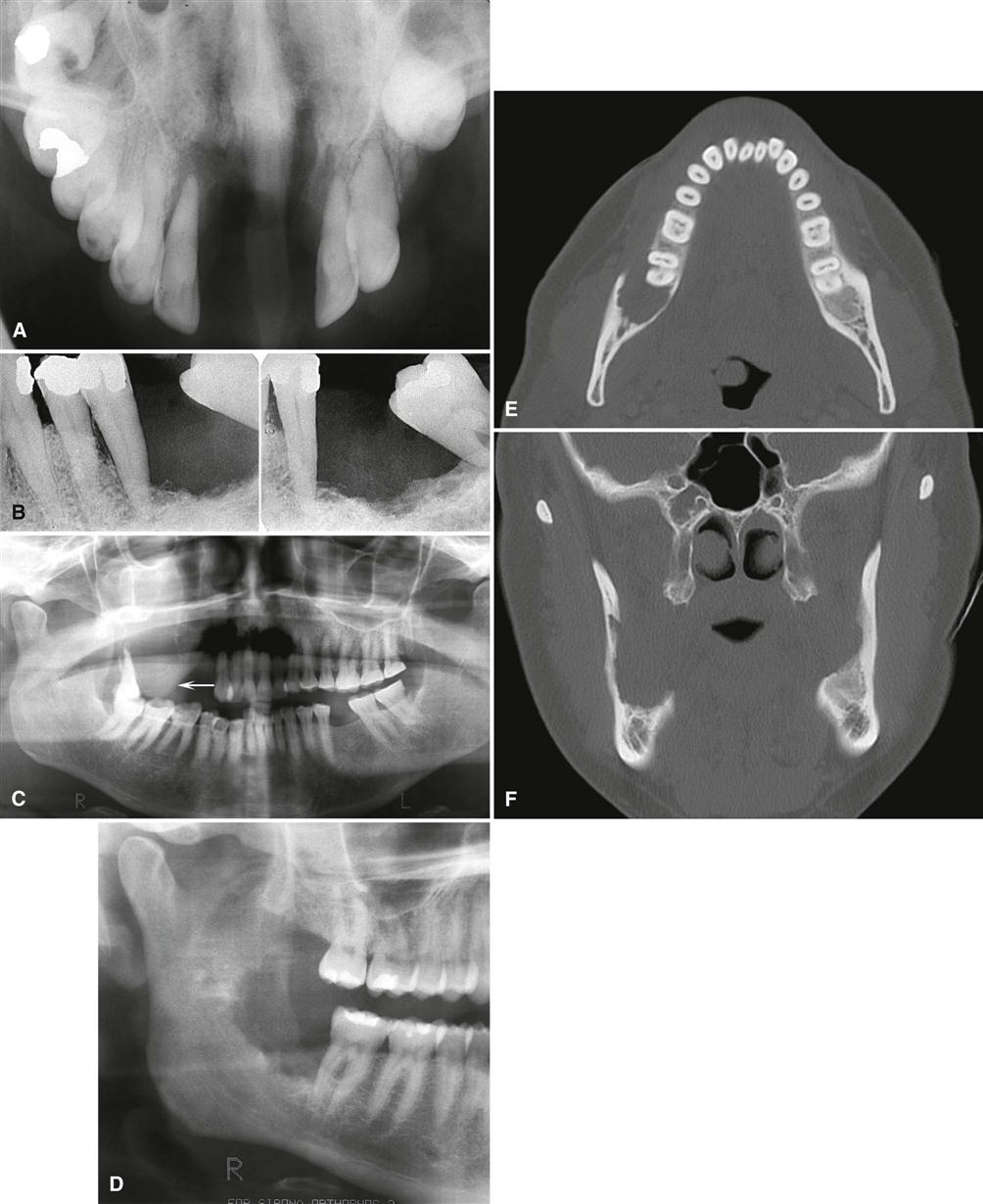

Squamous cell carcinoma may erode into underlying bone from any direction, producing a radiolucency that is polymorphous and irregular in outline. Invasion occurs in half of cases and is characterized most commonly by an ill-defined, noncorticated border (Fig. 24-2). Often the border appears well defined with a narrow transition band and smooth without any residual bone behind the border (see Fig. 24-2, E and F). Other lesions have an ill-defined border with a wide transition zone with finger-like extensions into the surrounding bone (see Fig. 24-3, C). If pathologic fracture occurs, the borders show sharpened thinned bone ends with displacement of segments and an adjacent soft tissue mass. Sclerosis in underlying osseous structures (likely from secondary inflammatory disease) may be seen in association with erosions from surface carcinomas.

Internal Structure.

The internal structure of squamous cell carcinoma in jaw lesions is totally radiolucent; the original osseous structure can be completely lost. Occasionally, small islands of residual normal trabecular bone are visible within this central radiolucency.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.

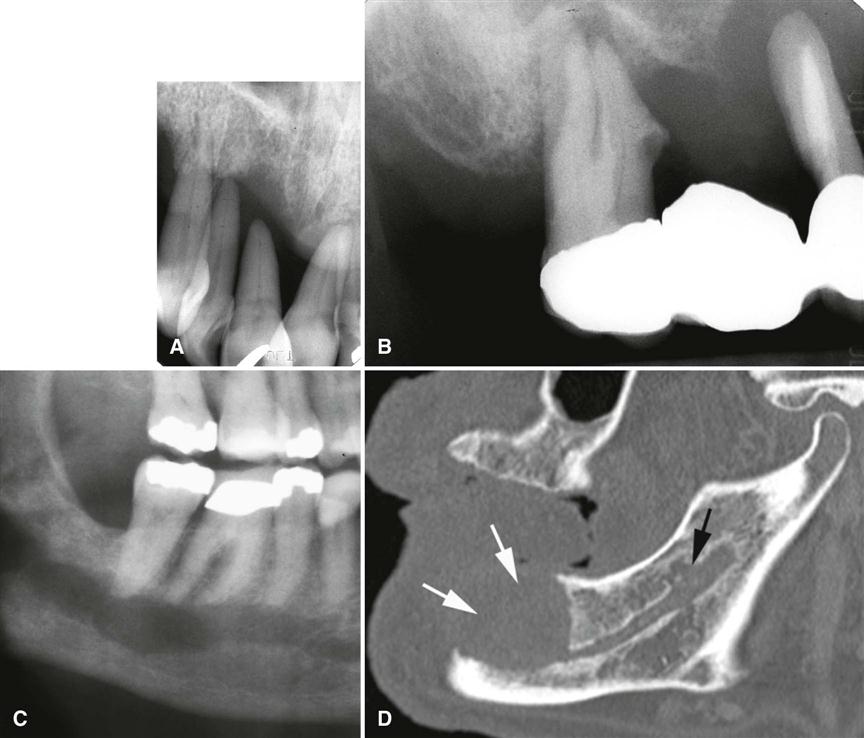

Evidence of invasion of bone around teeth may first appear as widening of the periodontal ligament space with loss of adjacent lamina dura. Teeth may appear to float in a mass of radiolucent soft tissue bereft of any bony support (Fig. 24-4, A and B). In extensive tumors, this soft tissue mass may grow with the teeth in it as “passengers” so that teeth are grossly displaced from their former position. Tumors may grow along the inferior neurovascular canal and through the mental foramen, resulting in an increase in the width and loss of the cortical boundary (Fig. 24-4, C and D). Destruction of adjacent normal cortical boundaries, such as the floor of the nose, maxillary sinus, or buccal or lingual mandibular plate, may occur. The posterior aspect of the maxilla may also be effaced. The inferior border of the mandible may be thinned or destroyed. If the tumor is extensive, pathologic fracture may occur.

Differential Diagnosis.

Squamous cell carcinoma is discernible from other malignancies by its clinical and histologic features. Occasionally, it is difficult to differentiate inflammatory lesions such as osteomyelitis from squamous cell carcinoma, especially when oral bacteria secondarily infect the tumor. Both osteomyelitis and squamous cell carcinoma can be destructive, leaving islands of osseous structure that may appear to be consistent with sequestra. Evidence of profound bone destruction or invasive characteristics helps to identify the presence of a malignancy when a mixture of inflammatory changes and carcinoma exists. Osteomyelitis usually produces some periosteal reaction, whereas squamous cell carcinoma does not. In cases of osteoradionecrosis, in which the patient has had prior malignancy, periosteal new bone is absent. If osseous destruction is present, the differentiation of this condition from squamous cell carcinoma requires advanced imaging and biopsy. The bone loss from squamous cell carcinoma originating in the soft tissues of the alveolar process may appear very similar to periodontal disease (see Fig. 24-3, A). Enlargement of a recent extraction socket instead of evidence of healing new bone formation can indicate the presence of an alveolar squamous cell carcinoma (see Fig. 24-3, B)

Management.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is usually managed using a combination of surgery and radiation therapy. The choice of which modality to use depends on the protocol of the treating center and the location and severity of the tumor. Generally, if an adequate margin of normal tissue can be obtained, surgery is the usual treatment, followed by radiation treatment. Alternatively, radiation may be used as the primary treatment followed by surgical salvage. The current trend is to add concomitant chemotherapy as an adjunct to either radiation or surgical treatment, which requires the dental practitioner to be aware of changes in the patient’s circulating blood count.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Originating in Bone

Synonyms

Synonyms for squamous cell carcinoma originating in bone include primary intraosseous carcinoma, intraalveolar carcinoma, primary intraalveolar epidermoid carcinoma, primary epithelial tumor of the jaw, central squamous cell carcinoma, primary odontogenic carcinoma, intramandibular carcinoma, and central mandibular carcinoma.

Disease Mechanism

Primary intraosseous carcinoma is a squamous cell carcinoma arising within the jaw that has no original connection with the surface epithelium of the oral mucosa. Primary intraosseous carcinomas are presumed to arise from intraosseous remnants of odontogenic epithelium. Carcinoma from surface epithelium, odontogenic cysts, or distant sites (metastases) must be excluded.

Clinical Features

These neoplasms are rare and may remain clinically silent until they have reached a fairly large size. Pain, pathologic fracture, and sensory nerve abnormalities such as lip paresthesia and lymphadenopathy may occur with this tumor. It is more common in men and in patients in their fourth to eighth decade of life. The surface epithelium is invariably normal in appearance.

Imaging Features

Location.

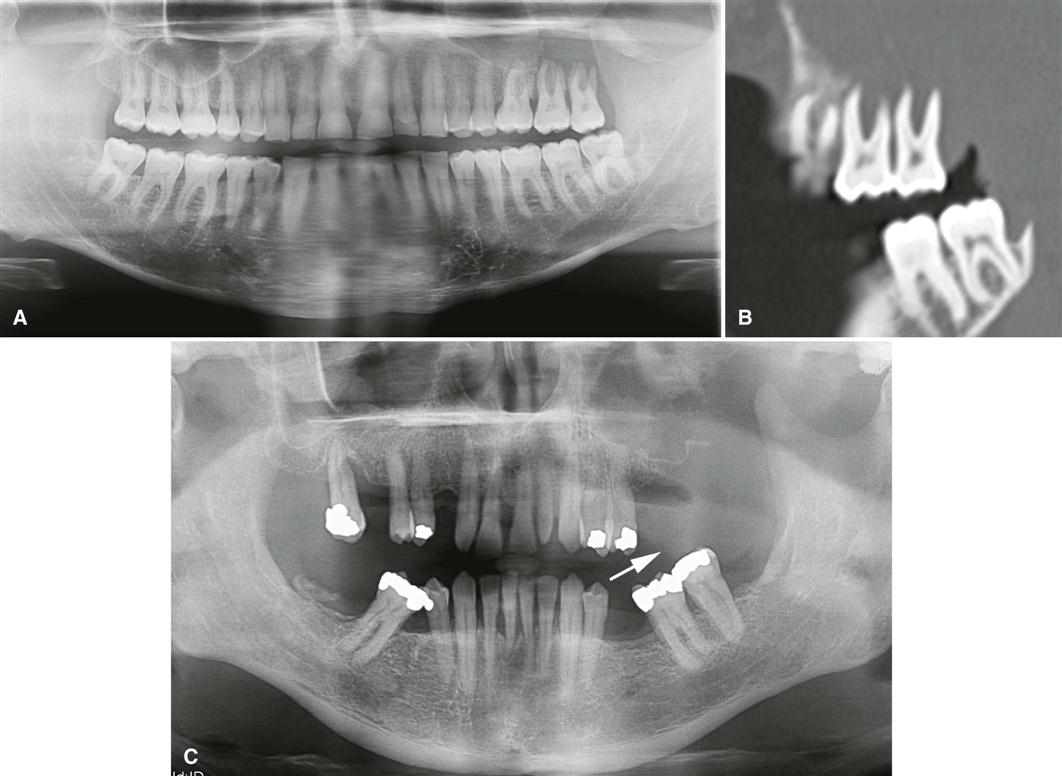

The mandible is far more commonly involved than the maxilla, with most cases being present in the molar region (Fig. 24-5) and less frequently in the anterior aspect of the jaws. Because the lesion is by definition associated with remnants of the dental lamina, it originates only in tooth-bearing parts of the jaw.

Periphery and Shape.

The periphery of most lesions is ill-defined, although some have been described as well-defined. They are most often rounded or irregular in shape and have a border that demonstrates osseous destruction and varying degrees of extension at the periphery. The degree of raggedness of the border may reflect the aggressiveness of the lesion. If sufficient in size, pathologic fracture occurs, with its associated step defects, thinned cortical borders, and subsequent soft tissue mass.

Internal Structure.

The internal structure is wholly radiolucent with no evidence of bone production and very little residual bone left within the center of the lesion. If the lesion is small, overlying buccal or lingual plates may cast a shadow that may mimic the appearance of internal trabecular bone.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.

These lesions are capable of causing destruction of the antral or nasal floors, loss of the cortical outline of the mandibular neurovascular canal, and effacement of the lamina dura. Root resorption is unusual. Teeth that lose both lamina dura and supporting bone appear to be floating in space.

Differential Diagnosis

If the lesions are not aggressive and have a smooth border and radiolucent area, they may be mistaken for periapical cysts or granulomas. Alternatively, if lesions are not centered about the apex of a tooth, occasionally it is difficult to differentiate this condition from odontogenic cysts or tumors. If the border is obviously infiltrative with extensive bone destruction, a metastatic lesion must be excluded as well as multiple myeloma, fibrosarcoma, and carcinoma arising in a dental cyst. Examination of the oral cavity and especially the surface epithelium assists in differentiating this condition from surface squamous cell carcinoma.

Management.

Generally, these tumors are excised with their surrounding osseous structure in an en bloc resection. Radiation and chemotherapy may be used as adjunctive therapies.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Originating in a Cyst

Synonyms

Epidermoid cell carcinoma and carcinoma ex odontogenic cyst are synonyms for squamous cell carcinoma originating in a cyst.

Disease Mechanism

Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a preexisting dental cyst is uncommon and excludes invasion from surface epithelial carcinomas, metastatic tumors, and primary intraosseous carcinoma. They may arise from inflammatory periapical, residual, dentigerous, and keratocystic odontogenic tumors. Histologically, the lining squamous epithelium of the cyst gives rise to the malignant neoplasm.

Clinical Features

The most common presenting sign or symptom associated with this condition is pain. The pain may be characterized as dull and of several months’ duration. Swelling is occasionally reported. Pathologic fracture, fistula formation, and regional lymphadenopathy may occur. If the upper jaw is involved, sinus pain or swelling may be present.

Imaging Features

Location.

This tumor may occur anywhere an odontogenic cyst is found—that is, the tooth-bearing portions of the jaws. Most cases occur in the mandible (Fig. 24-6), with a few cases reported in the anterior maxilla.

Periphery and Shape.

The radiologic picture of squamous cell carcinoma originating in a cyst mirrors the histologic findings. Because the lesion arises from a cyst, the shape is often round or ovoid. If it is a small lesion in a cyst wall, the periphery may be mostly well defined and even corticated. In this case, the radiographic differentiation from a normal cyst is impossible. As the malignant tissue progressively replaces cyst lining, the smooth border is lost or becomes ill-defined. The advanced lesion has an ill-defined, infiltrative periphery that lacks any cortication. Its shape becomes less “hydraulic” looking and more diffuse.

Internal Structure.

This lesion lacks any ability to produce bone. It is wholly radiolucent, perhaps more so than invasive surface carcinoma, owing to prior osteolysis from the cyst.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.

Carcinoma arising in dental cysts is capable of thinning and destroying the lamina dura of adjacent teeth or adjacent cortical boundaries, such as the inferior border of the jaw or floor of the nose. It can produce complete destruction of the alveolar process.

Differential Diagnosis

If a dental cyst is infected, it may lose its normal cortical boundary and appear ragged and identical to a malignant lesion arising in a preexisting cyst. However, inflamed cysts usually show a reactive peripheral sclerosis because of inflammatory products present in the cyst lumen. This sclerosis is not normally present in a cyst that has undergone malignant transformation. Nevertheless, the two may be difficult to differentiate radiologically, and cysts should always be submitted for histologic examination. Multiple myeloma may appear as a solitary lesion and may be difficult to distinguish, especially if it has a cystic well-defined shape. Metastatic disease may be similar, although it is commonly multifocal.

Management

The treatment of squamous cell carcinoma originating in a cyst is identical to the treatment described for primary intraosseous carcinoma.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma Originating in the Maxillary Sinus

Disease Mechanism

Risk factors for developing squamous cell carcinoma originating in the mucosal lining of the maxillary sinus include chronic sinusitis, chemicals used in manufacturing such as volatile hydrocarbons, isopropyl oils, wood dust, and metals such as nickel and chromium.

Clinical Features

These malignancies occur most commonly in patients of African and Asian heritage. Men are affected more commonly than women. The initial signs may be very similar to inflammatory disease and may include recurrent sinusitis, nasal obstruction, epistaxis, sinus pain, and facial paresthesia (see Chapter 26).

Imaging Features

These lesions may manifest with opacification of the maxillary sinus with soft tissue and destruction of osseous structures bordering the maxillary sinus, such as posterior wall of the maxilla, zygomatic process of the maxilla, floor of the maxillary sinus, walls of the maxillary sinus, and the adjacent maxillary alveolar process (Fig. 24-7). An associated soft tissue mass may also project into the oral cavity.

Central Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

Synonym

A synonym for central mucoepidermoid carcinoma is mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Disease Mechanism

Central mucoepidermoid carcinoma is an epithelial tumor arising in bone, likely originating from pluripotential odontogenic epithelium or from a cyst lining. It is histologically indistinguishable from its soft tissue counterpart. The criteria for diagnosis of a central mucoepidermoid tumor are the presence of intact cortical plates, radiographic evidence of bone destruction, and typical histologic findings consistent with mucoepidermoid tumor. Additionally, the practitioner must exclude the possibility of an invasive overlying mucoepidermoid tumor or odontogenic tumor.

Clinical Features

In contrast to other malignant tumors of the jaws, the central mucoepidermoid tumor is more likely to mimic a benign tumor or cyst. The most common complaint is of a painless swelling. The swelling may have been present for months or years and has been reported to cause facial asymmetry. Occasionally, it may feel as if teeth have been moved, or a denture may no longer fit. Tenderness rather than severe pain may also be present. Paresthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve and spreading of the lesion to regional lymph nodes have been reported. In contrast to other oral malignancies, central mucoepidermoid tumor is more common in females than males.

Imaging Features

Location.

The lesion is three to four times as common in the mandible as the maxilla, usually in the premolar and molar region with a few cases reported in the anterior mandible. The lesion most commonly occurs above the mandibular canal, similar to odontogenic tumors.

Periphery and Shape.

Mucoepidermoid tumor manifests as a unilocular or multilocular expansile mass (Fig. 24-8). The border is most often well defined and well corticated and often crenated or undulating in nature, which is similar to benign odontogenic tumors. The peripheral cortication may be impressively thick, which belies its malignant nature. Rarely, the periphery is not corticated and has a more malignant appearance.

Internal Structure.

The internal structure has features similar to a benign odontogenic tumor, such as a recurrent ameloblastoma. Lesions are often described as being multilocular or having either a soap bubble or a honeycomb internal structure, which is displayed as round radiolucent areas with or without thick or sclerotic bony peripheries. Also, there may be regions of amorphous sclerotic bone. This bone is not produced by the tumor but is merely remodeled residual bone.

Effects on Surrounding Structures.

Mucoepidermoid tumor is capable of causing expansion of adjacent cortical plates, often with perforation and sometimes extension into the surrounding soft tissues. Similar to benign tumors, the mandibular canal may be depressed or pushed laterally or medially. Teeth remain largely unaffected by this disease, although adjacent lamina dura may be lost.

Differential Diagnosis

Some characteristics of this tumor may appear similar to a benign odontogenic t/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses