Behavior Guidance of the Pediatric Dental Patient

Understanding the Child Patient: Review of Child Development

Variables Associated with Uncooperative Behavior

Setting the Stage for Successful Behavior Guidance

Review of Behavior Guidance Techniques

Documenting Behavior and Use of Behavior Management Techniques

Understanding the Child Patient: Review of Child Development

Cognitive Development

“Theories of cognitive development help clinicians to see the world through the eyes of children and show clinicians how children invest their experiences with meaning in age-specific ways”.1 Developmental theory is often presented in stages, which are periods of relatively stable behavior. The age that children reach a stage is variable, but the sequence is typically constant among healthy children. Jean Piaget’s stages of child development can help the clinician gain the perspective of the child patient as summarized in Box 23-1.

Prolonged verbal explanations for children in the preoperational and concrete operational stages often do not change behavior because limitations on the child’s reasoning skills make it difficult for children to fully understand verbal explanations of cause and effect and explanations of another person’s perspective.2 This reinforces the need for brief direct requests and commands versus long explanations.

Learning Theory

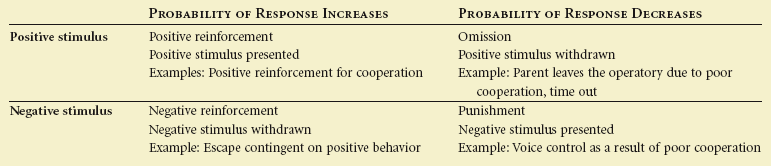

Learning theory asserts that behavior is learned and the response to past behaviors influences future behaviors. The theory of operant conditioning, summarized in Table 23-1, provides a framework to interpret many behavior guidance techniques such as positive reinforcement.

The knowledgeable practitioner understands that the complexity of child behavior cannot be explained by such a simplistic theory; however, it does have value. This theory can help explain how undesirable behaviors can be inadvertently reinforced. For example many behaviors of young children are reinforced by parental attention. Parents can inadvertently reinforce inappropriate behaviors by verbally correcting the child, and this verbal correction is a form of attention that reinforces the misbehavior.2 Therefore ignoring minor movement or intentional misbehavior may be better to extinguish this behavior.

Temperament

Those that treat children are aware that features other than genetics and environment shape child behavior. It is common to see widely varying behavior in families with shared environment and genetics, and this additional influence is thought to be temperament. “Temperament is normally used as a collective term for a set of developing traits that (1) manifest in an organized fashion during early life, (2) are relatively stable during significant periods of life, (3) are relatively consistent across situations, (4) have characteristic neurophysiologic underpinnings, and (5) are partially heritable”.3 In 1977 Thomas and Chess formulated three categories of temperament for children: easy temperament, difficult temperament, and slow-to-warm-up temperament, as described in Box 23-2.4

It is easy to imagine that children with an easy temperament can more readily meet the demands of the dental setting than difficult or slow-to-warm-up temperaments. Temperament has been linked to dental characteristics and behavior; for example shyness has been shown to be a factor associated with early childhood caries.5

Personality

Personality is the outcome of genetic predispositions to certain behavior influenced by environment. Pinkham asserts that children of high self-esteem who have favorable and positive assessments of adults will be able to meet the demands of dental appointments more easily than children with poor self-esteem and unfavorable views of adults.6 Poverty, dysfunctional family life, and abuse can lead to these findings.6

Variables Associated with Uncooperative Behavior

It would be helpful for the practitioner to predict which children will exhibit poor behavior in the dental setting; however, no one set of characteristics predict behavior management problems. Arnrup and colleagues7 concluded, “Children referred because of behavior management constitute a heterogeneous group. For most, but not all, dental fear is part of the problem. General fear, temperament behavioral symptomatology, and verbal intelligence all contribute to the characteristics of particular subgroups.”7

Dental Fear

The relationship between dental fear and negative behavior is not straightforward, and it would be an oversimplification to attribute all misbehavior to dental fear. The etiology of dental fear in children is multifactorial and a product of previous experience, generalized fear, and familial anxiety.8 However dental fears must be appropriately recognized and understood for proper patient management.9 Dental fear has been found in most but not all misbehaving children.7 It has been reported that 20% of children have dental fear and approximately the same percentage behave negatively. In one study, children with negative behavior had greater odds of having dental fear, and children with dental fear had greater odds of having negative behavior; but the groups were not identical. Children who report being fearful by various measurement tools are twice as likely to behave negatively than children who are not fearful.8

Pinkham classifies fears of dentistry as realistic and theorized fears.6 Realistic fears are previous bad experience, fears acquired from siblings and peers, and the fear of the needle.6 Dental fear is a worldwide problem and universal barrier to oral health services; fears acquired in childhood through direct experience with painful treatment or vicariously through parents, friends, and siblings may persist into adulthood.10

Dental fear has been attributed to lack of trust in the dentist and lack of control over a traumatic event.10 Dental techniques that help the patient regain trust and control may prevent or alleviate these fears. In regards to specific procedures, the dental injection was the most feared procedure, followed by “drilling” and “tooth scaling.”11 Other common fears were “feeling the needle” and “seeing the needle.”12 Needle phobia, however, does not imply a high level of children’s dental anxiety and diminishes with increasing age.13

Dental fear and anxiety is has also been linked to increased general fears.11 Dental fear itself may be a manifestation of another disorder, such as fear of heights, flying, claustrophobia and multiple other fears.10

Increased length of time since last dental visit and irregular dental visits are significantly associated with increased dental anxiety.11,14 Unfortunately the cycle of avoiding dental care, having increased need for invasive and emergent dental needs, and having a painful experience that reinforces avoidance can be observed in childhood and adolescence. Although we have established that pediatric dental behavior management problems and fear are different entities, because of their significant association, they will be discussed together as we explore variables related to uncooperative behavior.

Demographics

Most studies find that negative behavior in the dental office is most intense in younger children and decreases as children grow older.15 Dental anxiety also decreases with increased age16,17 and may be due to maturing communication and coping skills. However, it is important to assess the patient’s degree of psychological development because that may be more important than chronological age when predicting disruptive behavior.18

The role of gender in dental anxiety and misbehavior is not fully understood. Multiple studies have found no difference in dental anxiety and gender, whereas others have found increased anxiety in females, particularly after children pass early school age.11–15,17 Authors hypothesize that this is due to the increased willingness of females to verbalize fear. This variable is significantly influenced by cultural norms of appropriate gender roles and age of segregation of the sexes. Cultures that expect males to be “tough” and “act like men” may find boys less willing to report dental anxiety, which may skew outcomes of studies.

Culture may be defined as a system of shared beliefs, values, customs, and behaviors, that members of society use to cope with their world; it is a shared system of attitudes and feelings.19 Children are thought to increasingly be influenced by culture once they reach the formal operations stage of cognitive development. Although cooperation may be greater in cultures that place great stress on obedience, dental anxiety, typically based on behavior, may be overlooked.19

Some studies have linked dental anxiety and resultant behavior management problems to socioeconomic status and household characteristics,7,11,17 although others have failed to find this association. Explanations for this behavior may include increased caries history and resultant invasive treatment and/or lack of access to dentists with experienced treating children.20 Behavior management problems have also been linked to single parent homes,7 possibly due to increased economic and social pressures in these environments that will be discussed later in the chapter.

Temperament

Studies have shown that temperament, as measured by established psychological tools, can be significantly associated with behavior at a dental visit. Quinonez and coworkers21 found a significant association between the characteristic of shyness and disruptive behavior in a presurgical setting. Impulsivity and negative emotionality have also been more commonly found in children with behavior management problems.7 Patients with dental behavior management problems have been shown to be less likely to have a balanced temperament profile than control groups.3 These temperament profiles are a poor fit with the demands and formal structure of a dental visit.

Coping

Coping is the ability to deal with threatening, challenging, or potentially harmful situations and is crucial for well-being. Coping strategies may be behavioral or cognitive. Behavioral coping efforts are overt physical or verbal activities, whereas cognitive efforts involve the conscious manipulation of one’s thoughts or emotions.22 Self-statements focusing on competence, such as “I am a brave boy,” can help children tolerate uncomfortable situations for a longer period of time.23 Effective coping strategies enable the individual to perceive some sense of control over the stressful event. Typically, older children have a more extensive coping repertoire than younger children. Girls have also been reported to use more emotional and comfort-seeking strategies when faced with a stressful event, but boys use more physical aggression and stalling techniques. However, coping skills vary greatly among individuals. Studies involving venipuncture show that lower pain scores were associated with children who reported using behavioral coping strategies.22

Pain

The child in pain will naturally almost always exhibit behavior management problems. Pain is an inherently subjective experience and should be assessed and treated as such. Pain has sensory, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components that are interrelated with environmental, developmental, sociocultural, and contextual factors.24 Tissue damage is not required to provoke pain. It is important to take reports of pain seriously; it is counterproductive to argue with the child that a sensation is “uncomfortable but does not hurt.” If the child interprets a sensation as painful, it is important to take that perception at value and work from there. Introduction to new experiences through the tell-show-do technique can prevent patients from interpreting new sensations as painful.

Although we may consider adequate management of pain a certainty in providing dentistry for children, this has not always been the case. Historically, childhood pain has routinely been denied and undertreated.24 Milgrom and coworkers25 found in a 1994 survey found that “many dentists believe dental care for children is not particularly painful but only unpleasant, and a substantial proportion denies the reality of child dental pain. They tend to believe children confuse pressure with pain or knowingly present false or exaggerated responses, possibly in an attempt to escape the dental environment.”

One advantage to the highly fluid nature of pain is that, just as anxiety can upregulate pain perception, many of our behavior management strategies such as relaxation and distraction can downregulate pain. Hypnosis and mental imagery strategies can help patients modulate their own pain.26 This topic is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

Parental Anxiety

Dental anxiety of children is influenced by their family and peers.11 Parental anxiety, especially maternal anxiety, is especially influential on the child’s development of anxiety.14 The mother’s dental anxiety status (P < .001), the length of time since the mother’s last dental visit (P = .02), her regularity of dental attendance (P = .05), and her dislike of fillings (P = .008) were all significantly related to child dental anxiety status. The study concluded that maternal dental anxiety status and maternal psychiatric morbidity were both closely related to child dental anxiety status.18

Setting the Stage for Successful Behavior Guidance

The Dental Office

Many offices have new patient packets or websites that familiarize parents with office policies and set expectations. These may include letters directly to the children or activities for the children to prepare them for the visit. These are wonderful ways to introduce families to the office, but parents should be encouraged not to put too much emphasis on the visit because this may lead to negative stress. One study found no significant difference in the behavior of children aged 4 to 6 years if they were previously exposed to the office, either in person or by video, or were not exposed to the office.27

Scheduling

Conventional wisdom states that very young children are usually at their best early in the day. They may be able to tolerate a prophylaxis visit that is minimally demanding in the afternoon, but may be too tired later in the day for an operative appointment with higher levels of stress.28 Studies have not verified this and have actually found decreased negative behavior for restorative treatment in afternoon visits versus morning.15 This perception that children behave better in the morning may be due to the fact that the dentist typically has more energy early in the morning and is more likely to be on schedule and thus is better able to manage patients who need extra time and care. It is difficult to give our best effort to helping a child cope if we are tired from a busy day at the office. If a patient does have a difficult operative visit, reappointing them for a morning visit might be beneficial before resorting to advanced behavior management techniques.

Typically, dentists believe that a child needs an introductory visit to the office before performing an invasive procedure. Feigal refers to this examination or examination and prophylaxis only appointment as a “preconditioning appointment” and claims it helps ease children into the dental experience with as little stress as possible.29 However, Brill30 showed no difference in behavior between children who had an initial non-threatening dental visit and those who had a first restorative treatment visit. Thus emergent or urgent treatment should not be delayed on these grounds alone.

The Dentist and the Dental Team

The successful behavior guidance of a child is dependent on the dentist’s ability to communicate with the parent, child, and staff.31 Dentists who treat children can have a variety of personalities and still be effective. Some are very extroverted and emotive, providing an energetic atmosphere that makes children feel included and special. Other dentists tend to be more quiet and gentle to put patients at ease. This flexibility is beneficial because some children need upbeat encounters and others need quiet ones.26 As long as the underlying message is kindness and regard for the child’s well-being, dentists with almost any personality type can be successful at treating children.

The dentist’s appearance should be neat and professional. One study showed that parents significantly favor traditional styles of dress, such as the white coat, shirt, and tie, whereas children preferred the more casual attire. Many dentists avoid wearing a white coat, fearing that it will scare children; but in this study, both parents and children preferred the white coat to a pediatric coat.32 Protective gear required for universal precautions has not been shown to increase fear in children.33

The dental team should be a reflection of the office philosophy. The entire team should display a positive, friendly attitude toward the patient. Courses in communication, multicultural awareness, child development, behavior management, and informed consent for auxiliaries can help them become an integral part of successful behavior management.31 Using the same euphemisms and terms can help provide stability to the child patient.

Patient Assessment

To improve the child’s experience, it is important that the dentist get a good sense of the patient before treatment. At a minimum, the dentist should inquire about previous dental visits and the patient’s behavior at these visits. Previous disruptive behavior in the dental situation and previous extraction is significantly associated with dental anxiety status.14,18 Generally it is helpful to ask the parents how they feel the child will cooperate today, and it may also be helpful to ask how the patient copes with medical visits. Although this assessment is not always correct, it can help the dentist get a better sense of the child and parental expectations.

There are a number of questionnaires and surveys that can help the dentist gather more information about the fear, anxiety, and temperament of the child patient, although their clinical efficacy is unknown. A simple facial images scale with smiling, neutral, and frowning faces has been validated in children as young as 3 years to assess dental anxiety.34 The dental subset of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule has been used to determine fear in younger children,16 and the EAS Temperament Survey can gauge for temperament types more prone to distress, particularly shyness.21 There is often much to be learned from observing patients as they play in the waiting room, interact with parents, and respond to the initial approach of dental personnel.35 Pinkham36 describes in detail how the observation and parents’ interview can help the practitioner determine key information on behavior and behavior management techniques for individual patients.

Parents in the Operatory

One area of controversy is whether parental presence in the operatory helps or hinders behavior guidance, and there is no clear answer.37 Seventy percent of parents in one study wanted to be present in the operatory, and the majority said they were willing to assist should the dentist not be able to manage their children.38 The most recent survey of American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry members found that the majority of respondents indicated parents were present in the operatory routinely for emergency examinations (61%) and procedures involving special needs children (66%). Somewhat less than the majority (43%) indicated routine parental presence for examination and prophylaxis. Thirty-eight percent of respondents thought the phenomenon of parents being present had increased in the last 5 years.39

Having parents in the operatory provides an opportunity for immediate communication on changes in treatment plan, oral hygiene instructions, and postoperative instructions from the dentist rather than an intermediary. Also, it reduces the possibility of a parental misunderstanding or disagreement regarding how their child was treated. Finally, some dentists feel that the relationship with the parents is as important as the relationship with the children in order to establish trust. Venham and associates40 found no increase in negative behavior by children with parents’ presence. He also found that both children and parents prefer to remain together although this desire decreases with subsequent operative visits. This finding was corroborated by Pfefferle and coworkers41 in a study where parents were present as passive observers.

Natural parent behaviors such as reassurance can further complicate the scenario because they have been shown to contribute to child distress behavior.42 Every dentist who treats children can recount a time when a positive appointment was derailed by a parent’s inappropriate comment about pain or “the shot.” Dentists who never allow parents to be present report that it is not efficient, results in poor child behavior, and makes the dentist uncomfortable.43

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline Box 23-1

Box 23-1 TABLE 23-1

TABLE 23-1

Box 23-2

Box 23-2