22

Anterior open bite malocclusion

INTRODUCTION

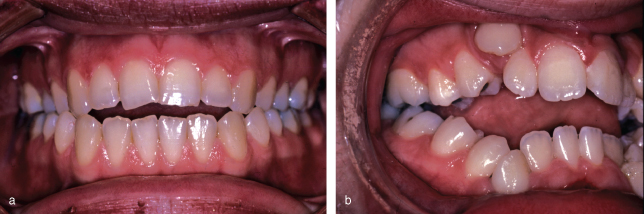

Anterior open bite (AOB) is present when there is no incisor contact and no vertical overlap of the lower incisors by the uppers.1 The severity varies, from almost an edge-to-edge relationship to a severe handicapping open bite (Figure 22.1a,b). It may occur with an underlying Class I, II or III skeletal pattern. The incidence in British children is 4% at age 9, falling to 2% by the early teens.2

Figure 22.1 (a) Mild dental anterior open bite. (b) Severe skeletal anterior open bite.

AETIOLOGY

AOB can be broadly divided into two categories:

- Dental open bite – where the vertical skeletal pattern is not contributory

- Skeletal open bite – where the open bite is at least partly due to the vertical facial form.

The causes of AOB can be subdivided into a number of areas.

Digit Sucking Habits

Digit sucking is a common cause of AOB. The incidence of digit sucking is around 30% at 1 year of age, reducing to 12% at 9 years and 2% by 12 years. Most persistent suckers are female.3 The severity of the malocclusion caused by the digit depends on the age of the patient and the intensity, frequency and duration of the habit.

The open bite caused by digit sucking is frequently asymmetrical, being greater on the side where the digit is inserted (Figure 22.2). The thumb or finger effectively acts as a barrier to the incisors erupting, while allowing excessive eruption of the posterior teeth. The upper incisors are invariably proclined whereas the effect on the lower incisors is more variable. Not infrequently there is a crossbite due to narrowing of the upper arch.

Figure 22.2 Severe anterior open bite due to avid thumb sucking. Note the asymmetrical appearance, the open bite being greater on the side the thumb is sucked.

Teeth displacement correlates better with number of hours sucking per day than magnitude of pressure. Children who digit suck for 6 hours or more each day, particularly those who sleep with a digit between the teeth all night, can have a significant malocclusion.4

Abnormal Tongue Function

A tongue thrust on swallowing is often noted in patients with an AOB. Two types of tongue thrust have been described:

- Primary (endogenous) tongue thrust

- Secondary (adaptive) tongue thrust.

Nearly all tongue thrust falls into the second category – the tongue is thrust forward on swallowing as an adaptive response to the presence of an AOB to prevent food/liquid/saliva escaping from the front of the mouth. The resting rather than dynamic position of the tongue has much greater influence on tooth position.5 When the tongue is naturally kept in a forward position overlying the lower incisors, a reverse curve of Spee is present in the lower arch (Figure 22.3).

Figure 22.3 Anterior open bite due to aberrant tongue function and posture. Note the characteristic reverse curve of Spee in the lower arch.

Endogenous tongue thrust is often associated with excessive circumoral contraction on swallowing. Treatment for AOB in a patient with an endogenous tongue thrust should not be attempted as relapse will almost certainly occur.

Skeletal Factors

Open bites may develop due to excessive vertical growth and are then termed ‘skeletal open bites’ (Figure 22.4). These are usually more severe in nature than dental open bites and only the terminal molars may be in contact. There is a significant increase in the lower anterior facial height (LAFH) and there may be vertical maxillary excess (VME). The Frankfort-mandibular planes angle (FMPA) is usually increased. Incisor eruption may be increased in relation to the underlying basal bone, although it still fails to compensate for the excessive vertical development of the jaws. Anterior facial heights are to a large extent under genetic control and hence taking a family history may be useful in growth prediction.6

Figure 22.4 Lateral cephalogram of a patient with a skeletal open bite.

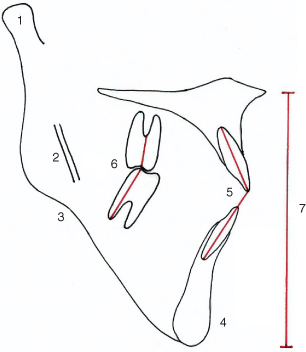

In growing patients a skeletal open bite tendency is in large part synonymous with a backward (clockwise) rotation of mandibular growth, and hence study of the structural features as identified by Bjork7 (Figure 22.5), may be more useful than conventional cephalometric analyses, in predicting how patients will grow and how they will respond to orthodontic treatment.

Figure 22.5 Bjork’s features indicating a posterior mandibular growth rotation. 1: Backward inclination of condylar head; 2: straight mandibular canal; 3: antegonial notch; 4: receding chin; 5: reduced interincisal angle; 6: reduced intermolar angle; 7: increased lower anterior face height.

Other Environmental Factors

These include:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses