CHAPTER 21

Orthodontics and Craniofacial Deformities

The treatment of patients affected by clefting and craniofacial anomalies can be both extremely rewarding and incredibly frustrating, owing to the myriad difficulties involved and the often long duration of treatment required. Care of these patients calls upon all the orthodontist’s skills and knowledge necessary to treat everyday children and adults, as well as additional skills and knowledge related to the unique challenges these patients often present. These challenges can include differences in psychological states of the patients and their parents, abnormalities of dental number, size, morphology, position, eruptive potential, etc., as well as similar abnormalities of the facial and jaw components. Concomitant medical conditions can also affect the treatment options, provision of care, and potential outcomes. The following chapter is dedicated to the practitioners willing to commit to the persistence, patience, and unique demands required by these patients.

1 What is the most common craniofacial deformity?

The most common craniofacial deformity is orofacial clefting, which affects all populations. Approximately 1 in 500–700 births will have some form of orofacial clefting: cleft of the lip, palate, or some combination of both.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

2 What are the common types of facial clefts?

3 When might cleft-affected patients be treated orthodontically/orthopedically?

Effective treatment of this type requires a specialized knowledge of these patients’ unique features and typically involves several periods of time at various ages. Because of the intensive nature of orthodontic therapy, performing it in stages is preferable to long-term continuous treatment. The potential treatment stages to be considered are based on four developmental stages: infancy, primary dentition, mixed dentition, and permanent dentition. Orthodontic treatment will often be provided at several of these developmental stages.

4 What is “presurgical orthopedics”?

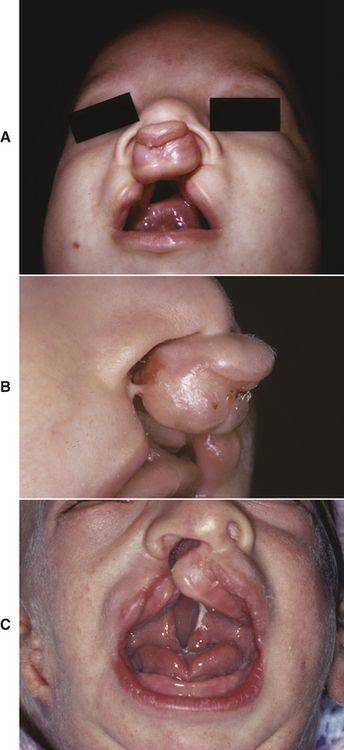

Orthopedic treatment of cleft-affected infants provided prior to any surgical lip or palate procedures, or presurgical orthopedics, was once routinely accepted as a necessary practice because of the dramatically distorted appearance of the maxilla at birth (

FIG 21-1 A and B, Unrepaired complete clefts of the lip and palate. Bilateral; note the posterior arch collapse, the protrusive premaxilla, short columella, and separation of the lip segments. C, Unilateral; note the distorted alveolar segments.

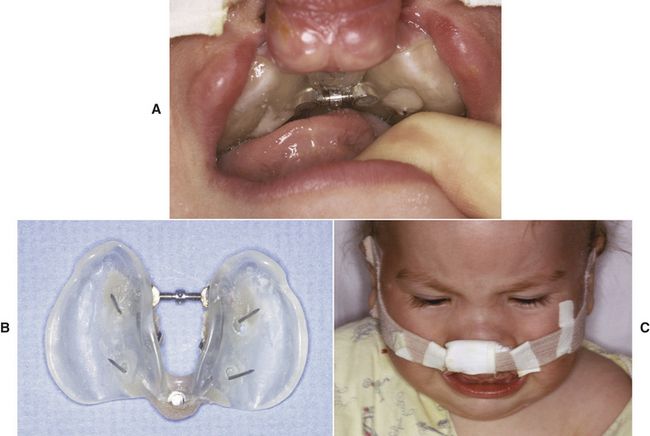

Although still controversial, presurgical orthopedic treatment with appliances addresses excessive maxillary distortion, especially in cases of bilateral cleft. Pin- or screw-retained “jackscrew” type or spring-loaded appliances (

FIG 21-2 A, An infant orthopedic expansion appliance using a midpalatal screw (jackscrew) and posterior hinge to expand the anterior portion of the lateral palatal shelves to allow retraction of the premaxilla. B, Palatal side of appliance. Note the stainless-steel “staples” that are driven into the palate to maintain the appliance. C, An extraoral elastic traction band placed across the premaxilla to provide retraction following expansion of the posterior segments.

Today, at some centers advocating early orthopedic treatment, primary alveolar bone grafting or periosteoplasty is performed at the same time as lip closure, to provide a better arch form, fewer fistulae, and decreased need for secondary bone grafting. Treatment choice must be determined by balancing the potential iatrogenic risks of presurgical expansion (e.g., damage to tooth buds, aspiration of materials, anesthetic and surgical procedural risks) with the positive benefits of treatment outcomes.

5 What orthodontic treatment may be indicated for cleft-affected patients in the primary dentition?

Depending upon developmental milestones, surgical closure of the palate is performed between 9 and 18 months of age, leaving a cleft of the maxillary alveolus and buccal and/or lingual fistulae. Orthodontic treatment during this phase is relatively rare, involving treatment of deleterious habits, functional shifts, or space loss after premature tooth loss. Fixed or removable habit appliances can be used to address digit habits and to correct crossbites (

Crossbite interference should be eliminated to prevent consequent unfavorable jaw growth, particularly if the patient has a functional shift of the mandible for intercuspation. Usually, selective reduction of the interfering teeth suffices, but some cases require orthodontic expansion, which may involve anterior and/or posterior expansion as well as long-term retention. However, if the maxilla has no bony continuity across the palate or alveolus, the corrected crossbite should be retained until secondary bone grafting provides that continuity.

Patients should be monitored for dental and overall development during this phase. In short-statured patients especially, delayed dental development may be due to growth hormone deficiency, because clefting is often associated with other midline defects, including pituitary and cardiovascular anomalies.

6 What orthodontic treatment may be indicated for cleft-affected patients in the mixed dentition?

EVALUATION OF NEEDS/TREATMENT PLANNING

Orthodontic evaluation and the development of long-term treatment objectives are needed at the start of this phase because of relatively rapid changes, as well as the developing social and self-awareness of the patient.

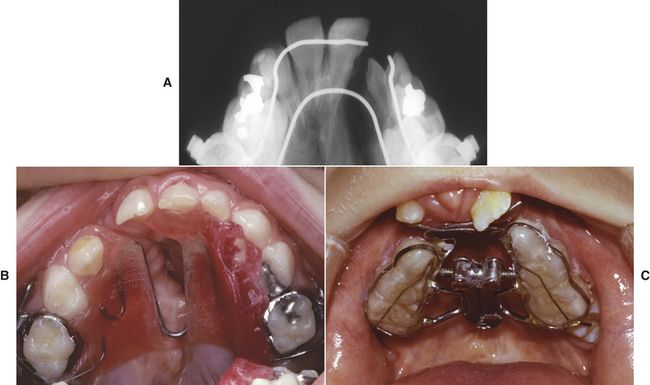

Most patients with cleft alveoli have a posterior crossbite and malaligned maxillary incisors at this stage. The collapse of the maxillary segments, especially in bilateral cases, can be severe (

ELIMINATION OF TRAUMATIC OCCLUSION

A stable maxilla is necessary for bone graft healing. Thus, traumatic occlusion of teeth in the cleft region should be eliminated, when possible, through alignment of the offending (usually maxillary incisor) teeth. Great care must be used to prevent moving the roots into the cleft site, and adequate retention is recommended to allow reformation of the cortical bone along the root prior to surgical exposure. It is often best to delay orthodontic alignment until after the graft because commonly there is only a thin layer of bone along the cleft side of the roots of adjacent teeth (

FIG 21-5 Examples of expansion appliances in cleft-affected patients. A, Radiograph of a “W”-arch; note the thin layer of bone on the lateral aspect of the central incisor in the cleft edge. B, Removable maxillary expansion appliance; note the lingual shelf of acrylic on the side of the greater segment to utilize the lower arch to reinforce anchorage and provide greater expansion of the lesser segment. Inverted “W” stainless-steel wire spring provides for expansion anteriorly. C, Bonded “fan” appliance in a patient with bilateral cleft lip and palate. The appliance uses posterior occlusal coverage to prevent traumatic occlusion of the incisors, since the premaxilla is flared by the lingual wires. Note that this appliance preferentially expands the anterior portion of the collapsed palatal shelves.

PRE-GRAFT EXPANSION

The amount and timing of pre-graft expansion should be planned in consultation with the surgeon. Whereas expansion is valuable before bone grafting to optimize surgical access, segments must not be expanded beyond the limits of surgical closure. The ideal expansion would provide coordinated maxillary and mandibular arch forms. If this interferes with the graft prognosis, three options are posed: delay the graft until adolescence and unite the segments with orthognathic or distraction surgery; perform the graft with little or no expansion and attempt expansion later (which may require surgical assistance); or accept the crossbite. If the patient is expected to need orthognathic maxillary advancement later, less expansion is indicated. Delaying the graft until adolescence may negatively affect the eruption or orthodontic movement of adjacent teeth, which could cause periodontal defects, caries, and social stigmata. In unilateral cleft-affected patients, further expansion is fairly predictable after alveolar bone grafting, although arch form may be compromised. However, post-graft expansion is less predictable in the bilateral situation, with the increased scarring and lack of a functional maxillary midline suture.

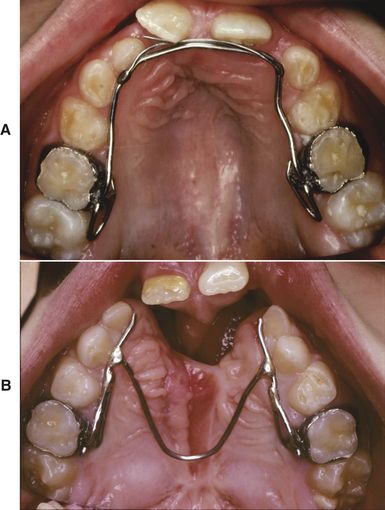

There are several appliance designs that can be used for expansion: fixed-spring appliances (e.g., quad-helix, W-arch or combinations; see

FIG 21-6 A “trombone”-style appliance uses elastic chain to advance the premaxilla out of crossbite. A separate expansion appliance is then used posteriorly followed by alveolar ridge bone grafting.

FIG 21-7 A, A fixed lingual arch maintains expansion after placing an alveolar bone graft and incorporating two finger springs to flare the central incisors. B, A modified “W” or lingual arch maintains the expansion obtained, while allowing surgical access for the alveolar bone graft.

An alternative approach advocates alveolar bone grafting at a younger age (5–7 years) followed by orthodontic stimulation of the graft by rapid expansion with a fixed-expansion (e.g., jackscrew type) appliance (see

MAXILLARY PROTRACTION

Following graft stabilization and initial incisor alignment, an orthodontic assessment is indicated to evaluate the patient’s pattern of maxillary and mandibular growth. Discordant monozygotic twin studies have revealed differences based on the type and severity of the cleft.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses