The Periodontal Pocket

The periodontal pocket, which is defined as a pathologically deepened gingival sulcus, is one of the most important clinical features of periodontal disease. All different types of periodontitis, as outlined in Chapter 4, share histopathologic features, such as tissue changes in the periodontal pocket, mechanisms of tissue destruction, and healing mechanisms. However, they differ with regard to their etiology, natural history, progression, and response to therapy.32

Classification

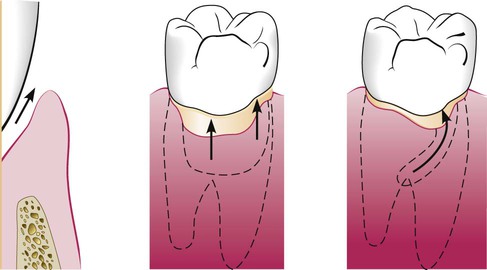

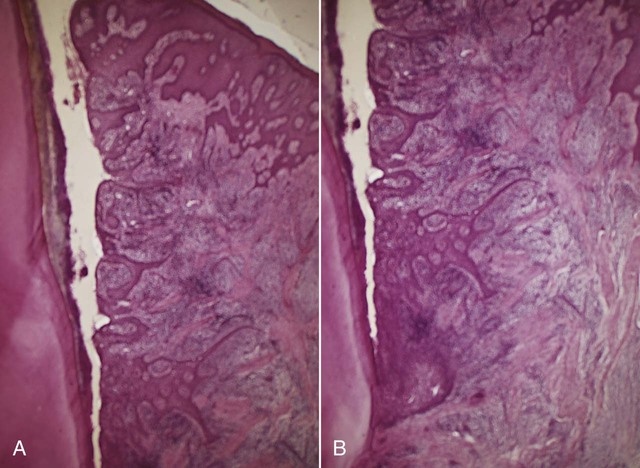

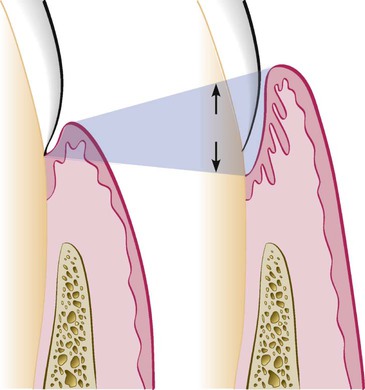

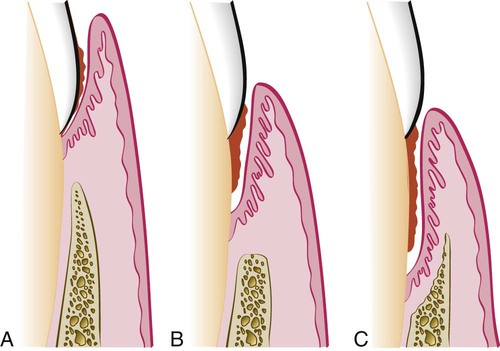

Deepening of the gingival sulcus may occur as a result of coronal movement of the gingival margin, apical displacement of the gingival attachment, or a combination of the two processes (Figure 20-1). Pockets can be classified as follows:

Gingival pocket is formed by gingival enlargement without destruction of the underlying periodontal tissues. The sulcus is deepened because of the increased bulk of the gingiva (Figure 20-2, A).

Periodontal pocket produces destruction of the supporting periodontal tissues, thereby leading to the loosening and exfoliation of the teeth. The remainder of this chapter refers to this type of pocket.

Two types of periodontal pockets exist, as follows:

Suprabony (supracrestal or supraalveolar) occurs when the bottom of the pocket is coronal to the underlying alveolar bone (Figure 20-2, B).

Intrabony (infrabony, subcrestal, or intraalveolar) occurs when the bottom of the pocket is apical to the level of the adjacent alveolar bone. With this second type, the lateral pocket wall lies between the tooth surface and the alveolar bone (Figure 20-2, C).

Pockets can involve one, two, or more tooth surfaces, and they can be of different depths and types on different surfaces of the same tooth and on approximal surfaces of the same interdental space.30,38 Pockets can also be spiral (i.e., originating on one tooth surface and twisting around the tooth to involve one or more additional surfaces) (Figure 20-3). These types of pockets are most common in furcation areas.

Clinical Features

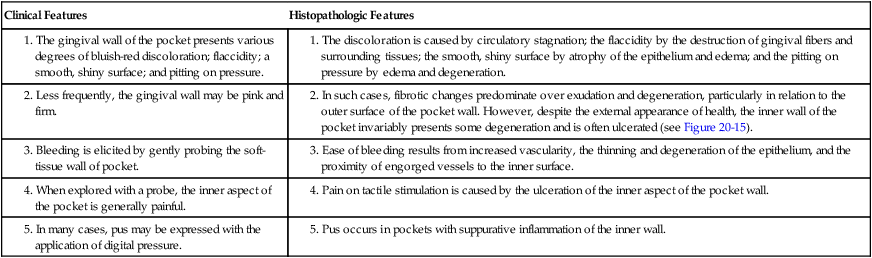

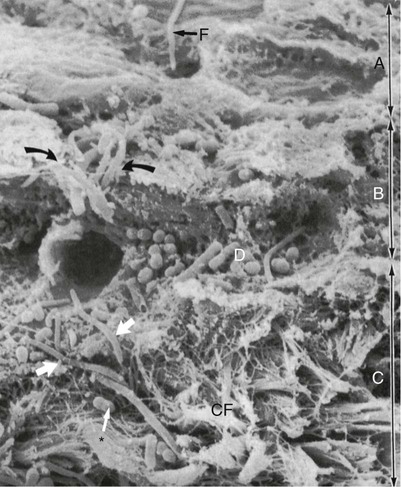

Clinical signs that suggest the presence of periodontal pockets include a bluish-red thickened marginal gingiva; a bluish-red vertical zone from the gingival margin to the alveolar mucosa; gingival bleeding and suppuration; tooth mobility; diastema formation; and symptoms such as localized pain or pain “deep in the bone.” The only reliable method of locating periodontal pockets and determining their extent is careful probing of the gingival margin along each tooth surface (Figure 20-4 and Table 20-1). On the basis of depth alone, however, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate between a deep normal sulcus and a shallow periodontal pocket. In such borderline cases, pathologic changes in the gingiva distinguish the two conditions.

2. In such cases, fibrotic changes predominate over exudation and degeneration, particularly in relation to the outer surface of the pocket wall. However, despite the external appearance of health, the inner wall of the pocket invariably presents some degeneration and is often ulcerated (see Figure 20-15).

For a more detailed discussion of the clinical aspects of periodontal pockets, see Chapter 30.

Pathogenesis

The initial lesion in the development of periodontitis is the inflammation of the gingiva in response to a bacterial challenge. Changes involved in the transition from the normal gingival sulcus to the pathologic periodontal pocket are associated with different proportions of bacterial cells in dental plaque. Healthy gingiva is associated with few microorganisms, mostly coccoid cells and straight rods. Diseased gingiva is associated with increased numbers of spirochetes and motile rods.40,41,43 However, the microbiota of diseased sites cannot be used as a predictor of future attachment or bone loss, because their presence alone is not sufficient for disease to start or progress.35

Early concepts assumed that, after the initial bacterial attack, periodontal tissue destruction continued to be linked to bacterial action. More recently, it was established that the host’s immunoinflammatory response to the initial and persistent bacterial attack unleashes mechanisms that lead to collagen and bone destruction. These mechanisms are related to various cytokines, some of which are produced normally by cells in noninflamed tissue and others by cells that are involved in the inflammatory process, such as polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), monocytes, and other cells, thereby leading to collagen and bone destruction. This chapter describes the histologic aspects of gingival inflammation and tissue destruction. For further information about the molecular biology aspects of these mechanisms of tissue destruction, please see Chapter 25 and www.expertconsult.com.

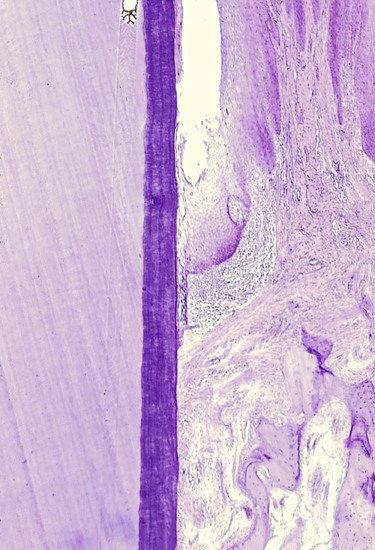

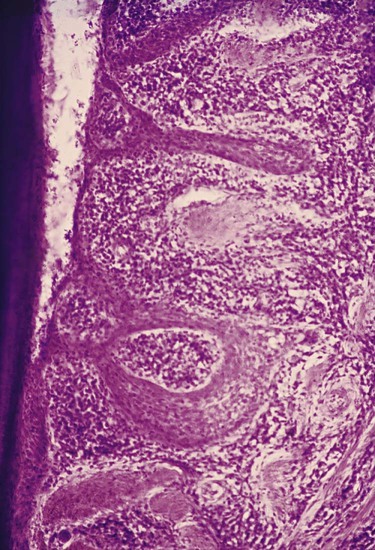

Degenerative changes seen in the junctional epithelium at the base of periodontal pockets are usually less severe than those in the epithelium of the lateral pocket wall (see Figure 20-7). Because the migration of the junctional epithelium requires healthy, viable cells, it is reasonable to assume that the degenerative changes seen in this area occur after the junctional epithelium reaches its position on the cementum.

Histopathology

Changes that occur during the initial stages of gingival inflammation are presented in Chapter 7. After the pocket is formed, several microscopic features are present, which will be discussed in this section.

For a detailed electron microscopic study of the pocket epithelium in experimentally induced pockets in dogs, see the article by Müller-Glauser and Schröder.49

Bacterial Invasion

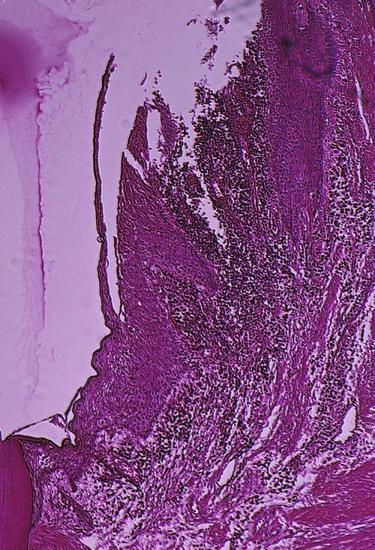

Bacterial invasion of the apical and lateral areas of the pocket wall has been described in human chronic periodontitis. Filaments, rods, and coccoid organisms with predominant gram-negative cell walls have been found in intercellular spaces of the epithelium.25,26 Hillmann and colleagues35 have reported the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia in the gingiva of aggressive periodontitis cases. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans has also been found in the tissues.16,47,58

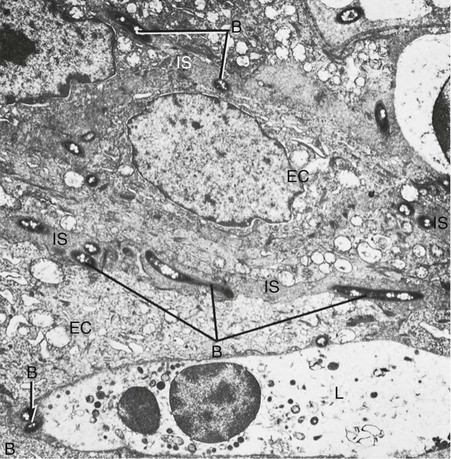

Bacteria may invade the intercellular space under exfoliating epithelial cells, but they are also found between deeper epithelial cells as well as accumulating on the basement lamina. Some bacteria traverse the basement lamina and invade the subepithelial connective tissue60 (Figures 20-10 and 20-11).

The presence of bacteria in the gingival tissues has been interpreted by different investigators as bacterial invasion or as the “passive translocation” of plaque bacteria.42 This important point has significant clinicopathologic implications and has not yet been clarified.17,39,43

Microtopography of the Gingival Wall

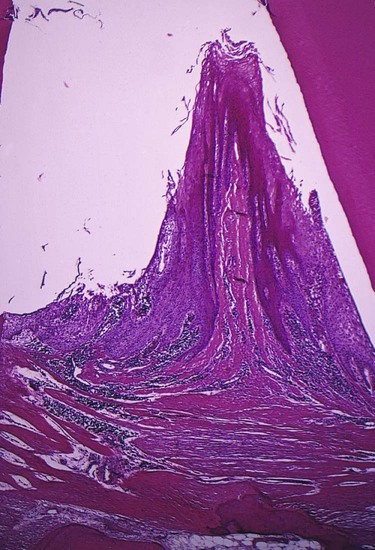

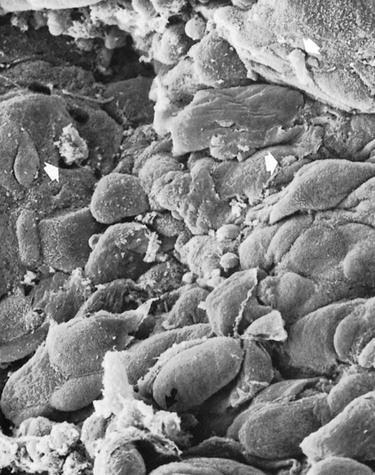

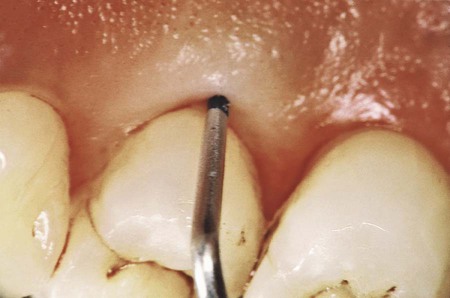

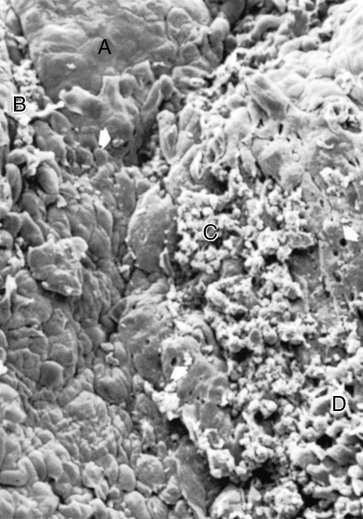

Scanning electron microscopy has permitted the description of several areas in the soft-tissue (gingival) wall of the periodontal pocket in which different types of activity take place.59 These areas are irregularly oval or elongated and adjacent to one another, and they measure about 50 to 200 µm. These findings suggest that the pocket wall is constantly changing as a result of the interaction between the host and the bacteria. The following areas have been noted:

1. Areas of relative quiescence, showing a relatively flat surface with minor depressions and mounds and occasional shedding of cells (Figure 20-12, area A).

2. Areas of bacterial accumulation, which appear as depressions on the epithelial surface, with abundant debris and bacterial clumps penetrating into the enlarged intercellular spaces. These bacteria are mainly cocci, rods, and filaments, with a few spirochetes (Figure 20-12, area B).

3. Areas of emergence of leukocytes, in which leukocytes appear in the pocket wall through holes located in the intercellular spaces (Figure 20-13).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses