Chapter 20

Problem Solving the Challenges Faced in the Restoration of Endodontically Treated Teeth

Problem-solving issues and challenges in the restoration of endodontically treated teeth addressed in this chapter are:

“I have made a diligent search to find whether or not teeth from which the pulp had been removed, and the canals and pulp chamber filled without admitting the fluids of the mouth, were subject to a similar deterioration of strength. It is now well known that teeth treated in this way retain their color almost perfectly; and from my observation of the relation of color to strength of the teeth I am prepared to entertain the suppositions that they retain their strength also. Only one tooth came into my hands with a root filling. It was a central incisor, and had not sufficient tissue for me to obtain a block; but it showed no undue percentage of water, and the color was good. Up to the present time I have been unable to obtain the history of the filling of this root.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

The concept of restoring endodontically treated teeth usually evokes challenging images of teeth with significant coronal tooth loss. In reality it may be the simple closure of an access cavity in a satisfactory coronal restoration to the total reconstruction of a tooth with no clinical crown due to the ravages of caries, faulty restorations or traumatic episodes, both short and long term (e.g., accidents, occlusal wear, abnormal function, etc.). Regardless of the clinical situation, the two primary objectives are to preserve the integrity of the root canal filling and rebuild the tooth into a symptom-free, functional, stable contributor in the patient’s dentition.

In the last 25 to 30 years, a plethora of scientific studies, clinical-technique articles, and the introduction of new materials have addressed the enigmatic issue of restoring an endodontically treated tooth.

In

Postendodontic and Intertreatment Temporary Restorations

With the initial access opening preparation, all caries, undermined tooth structure, and areas that are questionable relative to their integrity are to be removed or investigated (cracks, stained lines, etc.) so the tooth can be assessed for restorability prior to the actual root canal procedures. Some clinicians choose not to do these procedures, claiming there might be leakage if a wall were removed or if all the caries under a crown were eliminated. The claim is also made that the tooth cannot be isolated properly if specific tooth structure is removed. In essence, these approaches destroy the problem-solving concept and actually create environments conducive for problems. For example, salivary and bacterial leakage through carious dentin or poorly placed temporary materials can cause interappointment flare-ups and the opportunity for bacteria and their biofilms and byproducts to gain a foothold into an open canal or even one that has been obturated (see

As a basic principle in restorative dentistry, restorations usually leak in time, and no materials are perfect. When considering temporary restorative materials for endodontic access openings, everything will leak sooner rather than later.

Many premixed preparations have enjoyed popularity as interim or post root-treatment temporary filling materials, such as Cavit (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) or IRM (Dentsply Caulk, Milford, DE, USA). Laboratory studies indicate, however, that their ability to prevent the ingress of bacteria over time is poor.

While all materials leak to some extent,

The placement of a temporary post and core creates a different set of circumstances, especially as it relates to an impervious seal.

A better consideration for a temporary filling, if the tooth is not to be restored permanently in the immediate future, would be placement of a temporary material to the pulpal chamber floor without the use of a cotton pellet.

If temporary materials are used to fill the entire chamber in lieu of an orifice barrier, they may create a problem for the restoring clinician for two reasons. Firstly, careful removal of the material at the time of restoration is essential to prevent gouging the pulp chamber floor or walls or removing excess tooth structure in the cervical area. Secondly, weakening of the tooth in this area is a potential problem relative to future tooth fracture. Retention of sound dentin, especially in the cervical portion of the tooth, is very important. Thirdly, if eugenol-based materials have been used, future bonding in the chamber may be affected.

None of the laboratory studies that have investigated the efficacy of many of the temporary filling materials has included perhaps one of the most devastating of complications, namely the forces of occlusion on a temporary filling over time. Under clinical conditions and involving access cavities in the occlusal surfaces of teeth in function, the ability of any temporary restoration to maintain a seal is questionable. This is especially true in occlusional relationships with deep plunging cusps that can destroy the temporary, resulting in coronal leakage or in tooth fracture. These potential problems have been identified by some as a rationale for one-visit root canal treatment for all teeth; however, it does not consider those patients who delay the ultimate restorative process.

For interappointment temporary fillings, the most reasonable approach to prevent bacterial ingress would be to use calcium hydroxide as an intracanal medicament or, as some studies have pointed out, the combination of chlorhexidine and calcium hydroxide (see

A second complication that may arise with the use of temporary filling materials over long periods of time is the presence of unrestored post space.

Regarding the use of intermediate restorative material (IRM, Dentsply Caulk, York, PA, USA) as a temporary material, the issue of a eugenol-based material is controversial relative to the ultimate use of a bonded restoration, composite, or core material for the final restoration.

There are other problem-solving concepts that must be addressed when using composites to restore access openings in root-treated teeth. First, while there are multiple generation bonding systems available for this purpose, the three-step adhesives (fourth generation) seem to work the best and are the most durable.

Postoperatively, the very best solution is to restore the tooth immediately and avoid temporization completely. If this approach is not possible, the treatment plan should seek to accomplish as much permanent closure of the root canal system as possible. The pulp chamber should be permanently restored immediately if a post is not required. If the tooth requires a post and core, it would be best to proceed to these procedures immediately on completion of the root canal treatment. The crown could be completed at a later time. An alternative would be temporary closure of the pulp chamber and immediate crown preparation so that the integrity of the root canal procedures and the internal anatomy could be further protected with a temporary crown. The important goal is the preservation of all the efforts made to clean, disinfect, and obturate the root canal system.

BOX 20-1 Case Study Highlighting the Problems Encountered With Failure to Restore Endodontically Treated Teeth in a Timely and Appropriate Manner

Case Study

A 49-year-old female was referred for evaluation of the mandibular right posterior teeth. She had a recent history of spontaneous pain episodes in the area and was now experiencing prolonged pain to heat. Clinical examination revealed a large carious lesion on the distal surface below the margin of the full gold crown of the mandibular right first molar (

FIGURE 20-1 A, Preoperative radiographic image of mandibular molars. Note carious defect on distal margin of crown on the first molar. B, Two months posttreatment with degraded temporary restoration. C, A 17-month reexamination radiograph indicating lesion on distal apex. D, Immediate postsurgical radiograph. E, Eight-month postsurgical radiograph indicating healing of the surgical site. F, Nine years after the surgery, a reexamination radiograph indicates failure of the root canal treatment in the mesial canals. G, Radiograph following nonsurgical revision of mesial canals. H, Nine-month reevaluation indicating healing of the lesion on the mesial apex.

Two months later, the patient called with the complaint that the temporary filling had come out. Upon examination, the IRM was found to be intact over the mesial orifices, but the distal canal was exposed to saliva (see

Seventeen months later, the patient was referred for evaluation of a draining sinus tract lateral to the mandibular right first molar. The tooth was now restored, and a radiograph indicated that a post had been placed in the distal canal. A large periapical lesion was identified on the same root (see

Nearly 9 years after the original treatment, the patient was referred again for reevaluation of the mandibular right first molar, as the referring dentist had discovered another draining tract in the buccal vestibule. The radiograph indicated that there was a periapical lesion at the apex of the mesial root which extended coronally to the furcation (see

Problem-Solving Analysis

In retrospect, the most obvious etiology for the multiple postoperative problems was coronal leakage that occurred before the final restoration of the tooth initially. This could be attributed to an inadequate temporary restoration and prolonged delays before permanent placement of the post and crown. Leakage into the prepared post space most likely accelerated the failure of the root canal treatment in the distal root. The most reasonable explanation for the eventual failure of the root treatment of the mesial canals was residual bacteria in the pulp chamber from the original leakage problem. If the tooth had been restored immediately and periods of temporization had been avoided, none of the subsequent problems would likely have occurred. These problems are identified daily in private practice and can be prevented with a cognizant approach to the protection of all root-treated teeth with immediate attention to proper restoration.

Restoring Access Openings

Root canal procedures are commonly required for teeth that have satisfactory existing restorations, primarily crowns that have good margins and no evidence or deterioration (if metalloceramic no obvious craze lines or fractures). In doing so, potential weakening of the restoration or the tooth structure supporting the restoration is a valid concern.

The crowns of many teeth are frequently reconstructed entirely of amalgam or composite resin filling materials. Following root canal treatment, it is common to repair the access cavities with restorations of the same material. Nevertheless, research has demonstrated that routine access through large, multiple surface amalgam restorations significantly compromises the fracture strength of the repaired restoration postoperatively.

For onlays and full crown restorations, the structural integrity of the underlying tooth structure and restorative materials is more of a concern than the structure of the crown itself. Therefore, the clinician should use a caries detector upon entry to ensure that there are no hidden carious pathways that have undermined the restoration.

The most significant structural consideration in making access though full crowns is the presence of ceramic material. As discussed in

The metallic ring in the metalloceramic crowns is usually not significant when restoring an access opening. However, if the occlusal boundaries of the access opening are all metal, then some type of mechanical adhesion is necessary.

Traditionally it has been common in restorative dentistry to place a cement base for deeper preparations. A more contemporary evolution of this concept is the intracoronal barrier as discussed above. Research has recently shown the effectiveness of sealing the canal orifices against coronal leakage with a 3-mm layer of glass ionomer cement, flowable composite resin, compomer, or MTA.

FIGURE 20-2 A, Access cavity to be restored following routine root canal treatment. Sealer has been thoroughly removed with solvent. B, Acid etch. C, Placement of the bonding system. D, Light curing of bonding system. E, Placement of compomer in 1-mm increments. Each increment is light cured, creating an intracoronal barrier. F, Remainder of cavity is restored with composite resin. G, Resin restoration cured. H, Completed restoration.

Problem-Solving Key Factors That Influence Restorative Choices in Anterior and Posterior Teeth

Multiple factors that must be considered in choosing the final restoration include:

Alterations in the tooth that result in the potential for structural weakness are not attributable to changes in moisture content,

Restoration of Anterior Teeth

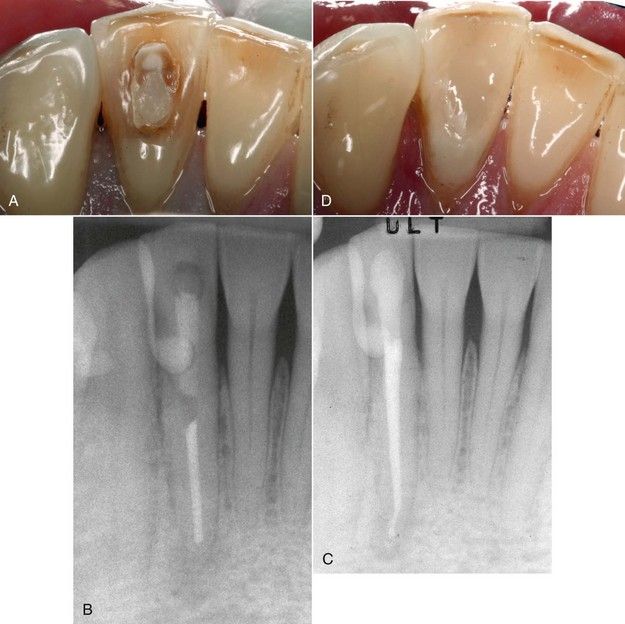

The use of a composite resin in combination with dentinal bonding systems is the restorative material of choice in teeth that have intact marginal ridges, cingulum, and incisal edges.

FIGURE 20-3 A, Mandibular incisor with failed access restoration. B, Periapical lesion resulting from treatment failure. C, Completed revision with satisfactory intracoronal barrier and final restoration. D, Clinical view of restoration.

Some root-treated anterior teeth require complete coronal coverage. The most common indications are loss of tooth structure in the incisal half of the crown from trauma or from fracture associated with large or multiple restorations. Such heavily restored teeth often become unaesthetic as well through staining and wear. Full coverage is both aesthetic and durable and should be considered routinely in these situations.

The retention of a sound cingulum in anterior teeth also appears to be a major consideration, especially as it relates to the “ferrule effect” to be discussed later in this chapter.

Restoration of Posterior Teeth

Primarily because of the loss of structural integrity and the amount of occlusal force during function, these teeth have a different set of restorative needs.

Of initial restorative concern is the seal of the pulp chamber. A separate intracoronal barrier should be placed before the construction of the final restoration begins. During core construction, care must be taken to insure that areas of deep excavation or fracture near the future crown margins are well sealed to prevent possible marginal leakage. When there is substantial remaining coronal tooth structure, any restorative material can be used for the core as the support for the crown is derived principally from dentin. However, if the coronal preparation would eliminate or reduce the remaining dentin thickness to where it is of no value, then a bonded composite or core paste-type material is indicated. If the final preparation will be in sound dentin, even a glass ionomer would be appropriate as a core buildup material, h/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses