The Tooth: Functions and Terms

• To identify the different functions of the teeth

• To identify the different tissues that compose the teeth

• To differentiate between clinical and anatomic eruption

• To define single, bifurcated, and trifurcated roots

• To recognize how the functions of teeth determine their shape and size

• To understand the individual functions and therefore the individual differences that exist among incisors, canines, premolars, and molars

• To name and identify the location of the various tooth surfaces

• To name and identify the line angles of the teeth

• To name and identify the point angles of the teeth

• To define the terminology used in naming the landmarks of the teeth

CROWN AND ROOT

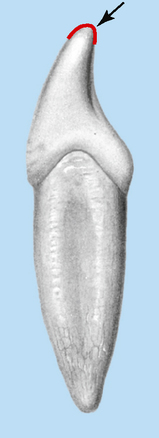

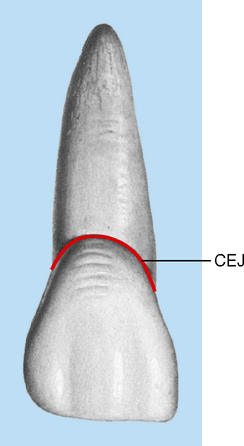

Each tooth has a crown and root portion. The crown is covered with enamel, and the root portion is covered with cementum. The crown and root are joined at the cementoenamel junction (CEJ). The line that demarcates it is called the cervical line, a line that is formed by the junction of the cementum of the root and the enamel of the crown (Fig. 2-1).

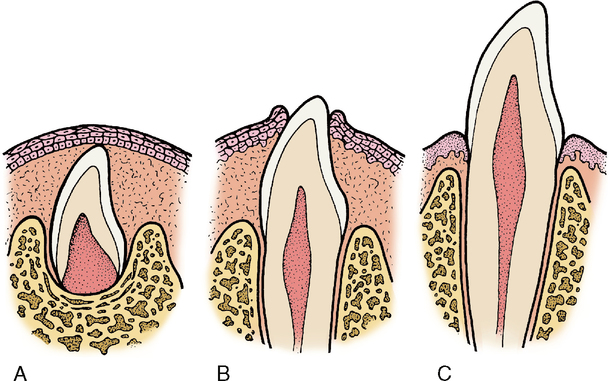

The crown portion of the tooth erupts through the bone and gum tissue. After eruption it will never again be covered with gum tissue. Only the cervical third of the crown in healthy young adults is partly covered by gingiva (gum tissue). The tooth continues to erupt from the bone and gingival tissue until all of the crown is exposed (Fig. 2-2).

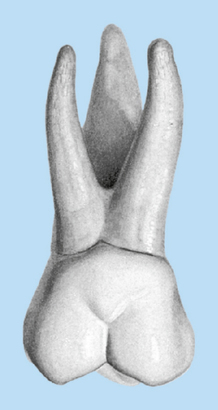

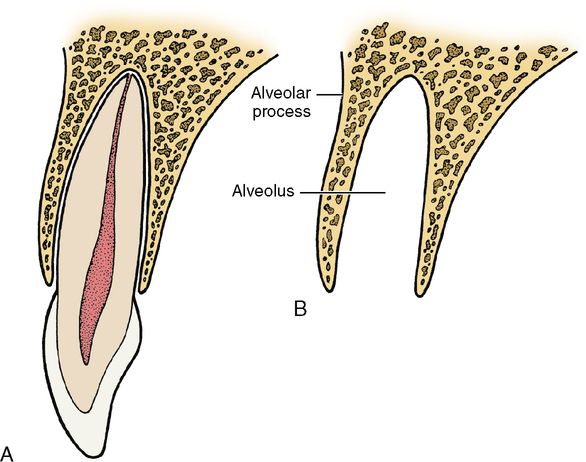

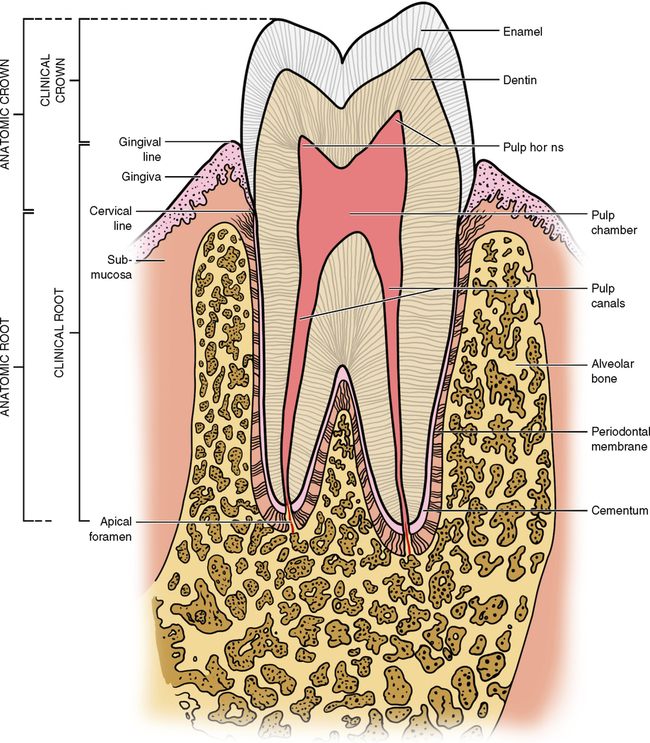

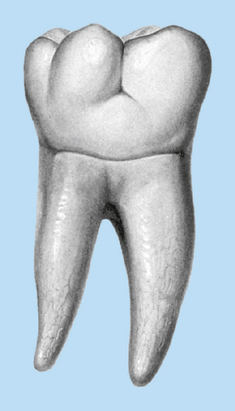

A clinical difference is evident between the amount of crown that could be erupted and the actual amount that is visible in the mouth. The anatomic crown is the whole crown of the tooth that is covered by enamel, regardless of whether it is erupted. The clinical crown is only that part seen above the gingiva. Any nonerupted area is not a part of the clinical crown of the tooth. Therefore, if all of the anatomic crown does not erupt, the part that is visible is considered the clinical crown, and the unerupted portion is part of the clinical root (Fig. 2-3). Eruption of a tooth is thus the moving of that tooth through its surrounding tissues so that the clinical crown gradually appears longer. The tooth may have a single root (see Fig. 2-1) or a multiple root with bifurcation or trifurcation—that is, division of the root portion into two or three segments (Figs. 2-4 and 2-5). Each root has one apex or terminal end. The root is held in its position relative to the other teeth in the dental arch by being firmly anchored in the bony process of the jaw. The portion of the jaw that supports the teeth is called the alveolar process. The bony socket in which the tooth fits is called the alveolus (Fig. 2-6). Teeth in the upper part of the jaw are called maxillary teeth because they are anchored in the maxillary bone. In the lower jaw they are called mandibular teeth because they are anchored in the bone called the mandible.

TOOTH TISSUES

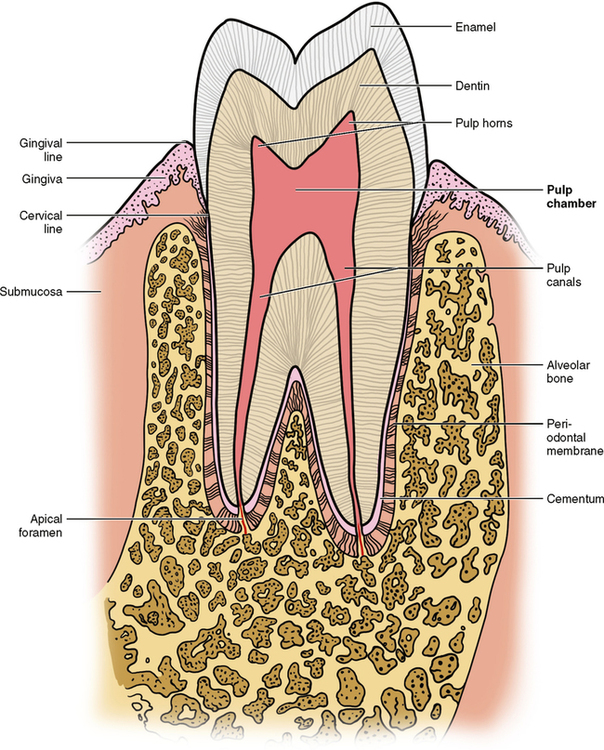

The four tooth tissues are enamel, dentin, cementum, and dental pulp (Fig. 2-7). The first three are hard tissues; the pulp is soft tissue.

Pulp

Anatomically the pulp is divided into two areas: the pulp chamber and the pulp canals or root canals. The pulp chamber is housed within the coronal portion of the tooth, and the pulp canals are located within the roots of the tooth. Together the pulp chamber and pulp canals are referred to as the pulp cavity; thus the pulp cavity runs the entire length of the interior of the tooth from the tip of the pulp chamber, the pulp horns, to the apex of the root canal (see Fig. 2-7).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses