Chapter 2

Smile Design and Veneers

Introduction

Beginning in the early in the 1990s, the smile slowly became an integral part of the total facial complex. The aesthetic appeal of a “Hollywood” smile started to surface as an important asset to a patient’s overall looks and appeal. Today there is a legitimate marriage between the creation of aesthetic facial and dental components to create a person’s look. The dentofacial relationship should be greatly considered when improving a patient’s appearance. Plainly stated, the entire aesthetic concerns, both facial and oral, need to be evaluated and addressed.

The challenge of combining the triad of phonetics, function, and aesthetics has always been the primary restorative goal of dentists. As the cosmetic savvy of patients increases, there becomes a demand to look at all of the aesthetic aspects that can be improved for a particular patient.

Understanding what a patient likes and dislikes about their appearance will help create a much better outcome. Oftentimes, the patient does not know what he or she is displeased about. It is up to the clinician to educate and guide the patient. To properly accomplish that, the clinician must be aware of all the treatment modalities that are available.

Aesthetic improvement procedures in plastic surgery, dermatology, and dentistry are in high demand by the populace and are within themselves interactive. Age-related changes in an individual’s appearance have become the key driving force for cosmetic enhancement (Figure 2.1).

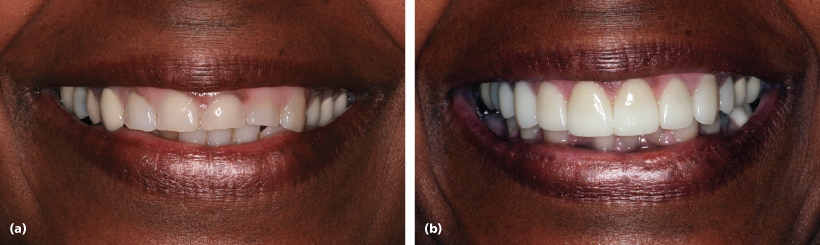

Figure 2.1 Improving one’s appearance is not necessarily restricted to the young. Age-related changes to a person’s smile can easily make a patient look and feel younger.

Cosmetic dentistry has grown tremendously from its inception. Although it was always the objective of dentists to restore teeth to their natural form, treating the dentition for purely aesthetic reasons began to develop and evolve with the discovery of both enamel and dentin bonding agents and the ability to etch porcelain. Prior to the modern era of bonding, Dr. Charles Pincus would attach specially made pieces of acrylic to an actor’s own dentition to improve their smile.1 Although not functional in nature, these early laminates did provide an improved aesthetic look. The dentist’s knowledge of the relationship between the gingival tissues, teeth, and the perioral area as related to aesthetics has vastly increased since this early beginning.

This expansion of cosmetic understanding by dentists was paralleled by the growth in the number of patients who became aware of what is considered to be a pleasing smile. Many Americans feel that a healthy, attractive smile is an important social asset. A survey performed by the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry revealed that more than 87% of adults feel that an unattractive smile can impede career success. In addition, 92% of the respondents said that an attractive smile is an important social asset.2

In a population where 50% of individuals are unhappy with their smiles, addressing this concern is a matter of importance. Even young people of today have an opinion about what a nice smile demonstrates. Teenage girls in the United Kingdom were asked to assess models in girl magazines. Models that appeared to be “cool” and “desirable” were deemed not to need orthodontic treatment.3 Although the dentist is the person that will deliver the restorative treatment, it is the responsibility of all health-care professionals who practice cosmetic procedures to recognize the importance of orodental aesthetics when rejuvenating and enhancing a person’s overall appearance.

The term smile makeover has become well infused into the vocabulary of our society. As a play on the facelift, the smile lift became a new concept in aesthetic dental care.4 Smigel described the nonsurgical facelift5 (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Increasing the arch by placing veneers will create the lift of the lips to show more teeth in the smile.

It represents an overall tooth-to-tooth, tooth-to-gums, tooth-to-lips, and tooth-to-face relationship. Smile makeovers are performed to improve the aesthetics of teeth not in balance and harmony. They could also be an attempt to rejuvenate smiles that have degenerated over the years through wear and tear (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Improving the patient’s occlusal and functional problems will result in an improved esthetic look.

The type of treatment that encompasses a smile makeover could be as simple as tooth bleaching to the complexity of a full mouth reconstruction. In the end, the treatment must fulfill both functional and aesthetic components. It can be said that good function will promote good aesthetics and vice versa. However, this does not mean that a smile that is unattractive does not function properly. The clinician must be fully aware that elective procedures should maintain or improve function, not impair it.

Teeth that have a dark shade, are creamy yellow, brown, gray, or a combination of these colors can create an unsightly smile. These color changes can occur slowly over many years as microporosities in enamel pick up staining from ingested food and drink, chemical exposure, or smoking. In addition, the discoloration can occur hereditarily. The ingestion of certain antibiotics (most notably tetracycline-containing medications) during the formative years of permanent tooth structure can cause teeth to turn gray-brown and sometimes have a petrified wood appearance. High levels of fluoride ingestion, usually from a water supply that is naturally fluoridated, can cause fluorosis, a condition in which the teeth may demonstrate unattractive white or brown mottled spots. Furthermore, dental discoloration can occur after trauma or secondary to endodontic treatment.

Bleaching of these discolored teeth is the most common and simplest method for improving one’s smile. In many dental offices, vital bleaching is the treatment of choice for initiating a change in a person’s smile. If the shape and position of the natural dentition are deemed correct and pleasing, then bleaching is the correct choice of treatment. In these instances, a shade change is the driving force for an improvement in the smile. Hydrogen peroxide is the active ingredient to bleach teeth. Different percentages can be delivered via a tray system or placed directly on the teeth in an office setting.

Over-the-counter (OTC) bleaching products are now available. It must be understood that these OTC products contain hydrogen peroxide in percentages that are considered cosmetic in nature, usually below 10%. With dosage of peroxide and time of application being the key components when bleaching, store-bought systems may not be efficient. Their bleaching agent mode of delivery is not precise enough to get an effect in a desirable time frame.

Dentist-controlled materials can range from 7.5% to more than 35% hydrogen peroxide. The peroxide can be in its true form or carried in a carbamide peroxide structure. Either is delivered in a tray that is customized for each patient, optimizing the dosage of peroxide delivered to the teeth. Home bleaching requires the patient to place the bleaching agent into their customized tray that is then placed over their teeth for a period of at least 2 weeks, 1–1.5 hours daily. Bleaching can be unpredictable; however, many people see a change that is demonstrable (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 In-office chairside bleaching can give immediate improvement to a smile. Over–the-counter and customized tray home whitening will show color improvement over time.

Smile aesthetics is a component of several factors that when harmoniously combined produce a pleasing smile. Each factor can be approached independently for evaluation purposes but must be addressed congruently when the patient is being treated.

When assessing the key components of a smile, those elements that determine it to be pleasing will help prepare the clinician to have a discussion with the patient since it evaluates the smile qualitatively. Educating the patient about deficiencies will help with the jointly chosen direction of the final treatment outcome. The presence or absence of these subtle aesthetic factors will help to demonstrate to the patient those things about which the patient may be unhappy.

An unattractive smile becomes so because there is a compounding absence of the essential elements that dictate what constitutes an attractive smile. In addition, understanding these principles will allow the clinician to treat the patient with a very predictable outcome. Understanding and mastering smile analysis will ultimately contribute to sound mechanical design and predictable outcomes.

For elective aesthetic procedures, it is important that the patient be educated about their smile deficiencies. Codiagnosis is an important principle for determining how the outcome will be viewed by the patient and the clinician. The perspective of the patient and the doctor should be coincidental, or at least as close as possible. The expectations of both parties should be clearly understood prior to the initiation of treatment.

Smile Design

The art of the smile is dependent on several factors that have their basis grounded in symmetry and proportions. Based on principles established by the ancient Greeks, mathematics had a direct relationship with philosophy of beauty.6 There is a geometric beauty as it relates to the face and the smile. Dr. Stephen Marquardt described a way to quantify facial and smile attractiveness with the use of a mathematical computer model.7 Combining this mathematical relationship of proportions and artistry is what describes smile design. It is the ability and responsibility of the cosmetic dentist to combine these philosophies into a perspective that makes sense from both an aesthetic and a functional view.

Smile analysis and the ultimate dental design and manufacturing involve not only the way the smile looks but also how it works functionally and biologically. There must be a conscious awareness that, despite the influence of art when creating a beautiful a smile, there is a respect for the balanced relationship that exists between biological, mechanical, functional, and aesthetic parameters.8 The cosmetic dentist must understand what an ideal shape of a tooth looks like and how it reacts under function. He or she must be able to place that correctly shaped tooth into a position that makes it harmonize with the surrounding teeth, gums, lips, and face. Once the smile is designed, both the dentist and the ceramist can select the correct material that will mimic nature and withstand the forces of time.

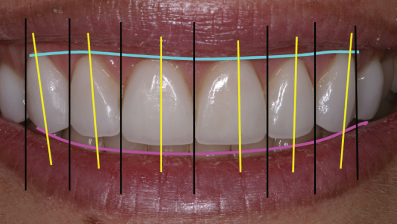

As previously stated, the smile can be broken down into several key components that will influence its attractiveness. Attention must be given to each of these since it is the absence of several of these factors which may create a smile that lacks balance and harmony (Figure 2.5). It is the final correction of these missing elements that will create an improved and pleasing smile.

Figure 2.5 Harmony and balance in the smile is created when principles are followed that relate to line angles and tangents.

Central Incisor Dimensions

The maxillary central incisor teeth are the dominating feature of the smile, just as the mouth is the foremost feature of the face. The eye is drawn to the upper two front teeth during conversation. If there is a lack of symmetry between the two maxillary central incisors, then there is a very noticeable decrease in aesthetics.

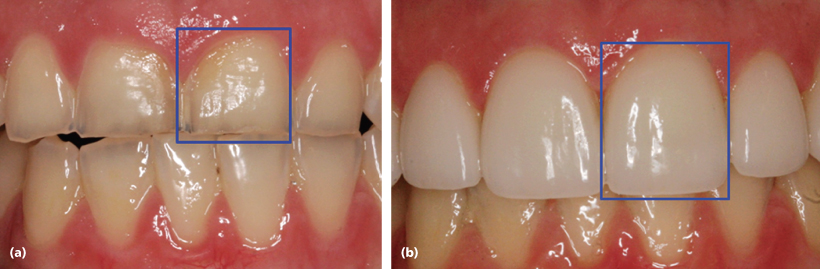

In general, the central incisors should exhibit a width–to-length ratio of 75–80%. The average length can range from 10.5 to 11 mm. Recent analytical studies of 44 central incisors confirm the widest central incisors to be 9.10–9.24 mm and the greatest length to be 11.69 mm. This demonstrated a width-to-length ratio between 78% and 79%.9 Robert Lee advocated an average central length up to 12 mm10 (Figure 2.6). However, there are variables that may affect the determination of the final length. Loss of collagen around the perioral area will have an influence on the amount of exposure of the upper teeth.

Figure 2.6 Centrals need to be symmetrical and have the correct width-to-length ratio. Ideally, it should be between 75% and 80%. Prior to being restored, the centrals were too square (a). A more rectangular look is more appealing (b). The two centrals were compromised both functionally and esthetically.

The amount of tooth displayed at rest could differ by as much as 3 mm between a 30- and 70-year-old person.11 With age there is a reverse correlation in upper and lower tooth display. As one becomes older, there is a tendency to show less of the upper teeth and more of the lower. Depending on the age of the patient being treated, the final length of the upper central incisors will be influenced by the amount of tooth that needs to be seen. A naturally low lip line or one that has fallen with age will require compensation in incisor length. This may result in a crown that is longer than 11 mm.

The functional aspect of the central incisors in regard to phonetics should be the determining factor when deciding the final length of the tooth. The incisal position of the central as compared with the lower lip is critical and cannot be compromised. Having the patient pronounce “F” and “V” sounds will determine proper central incisor length and facial position. The incisal edges should hit the wet/dry line of the lower lip.12 Once this position is determined it cannot be changed. The patient’s feedback is critical to determining the length as it relates to aesthetics and function of these two important front teeth.

Central Incisor Midline Analysis

Creating symmetry between the central incisors correlates directly with how these two teeth integrate with the lips and the face. The imaginary lines that determine the midline of the face have been described as a vertical line that extends through the forehead, nose, dental midline, and chin. The midline can also be described as being located in the center of the face, with a line drawn perpendicular to the interpupillary line. Ideally, the midline between the central incisors should coincide with the midline of the face. This should give the most pleasing look. However, research by Bodden et al. indicates that this is not necessarily so. They found that in 70% of the observed cases, the central midline coincided with the facial midline, using the lip philtrum as a guide. This research revealed that slight deviations away from the 70% did not have a negative impact on overall aesthetics.13 In addition, it was found that 75% of the time, the upper and lower dental midlines did not coincide at all. Given this information it may be concluded that the position of the maxillary central incisor midline as compared with both the facial midline and lower tooth midline is not the critical issue when dealing with smile aesthetics.

What will highlight a disjointed smile is when the midline of the two centrals is canted or slanted. The disharmony that occurs even if the midline is placed in direct correlation with the midline of the face will create an unpleasing look.14 Oblique lines create asymmetry, creating an unacceptable smile (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7 Upper central incisors do not need to align with the midline of the lower/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses