CHAPTER 2

Development of the Occlusion

Development of the occlusion, in other words, eruption of the teeth and formation of the interrelationship between the teeth of the upper and lower jaws, is a genetically and environmentally regulated process. Coordination between tooth eruption and facial growth is essential to achieve a functionally and esthetically acceptable occlusion. Most orthodontic problems arise through variations in the normal tooth eruption/occlusal developmental process. Therefore, every developing malocclusion and dentofacial deformity must be evaluated against normal development.

In this chapter, normal eruption timing and sequence of primary and permanent teeth is discussed. Since occlusion is regarded as a dynamic rather than a static structure, changes in the dental arch dimensions are then discussed. Finally, various common deviations in the occlusal development are addressed.

1 What are the stages of tooth development?

Tooth development is a genetically regulated process characterized by interactions between the oral epithelium and the underlying mesenchymal tissue.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

From this stage the epithelium can be called the enamel organ. It gains a concave structure; therefore, this stage is called the cap stage. A third structure, the dental follicle, originates from the dental mesenchyme and surrounds the developing enamel organ. During this stage the shape of the crown becomes evident, but the final shaping of a tooth occurs during the next stage, called the bell stage. During the bell stage cytodifferentiation begins and tooth-specific cell populations are formed. Some of these cells differentiate into specific dental tissue-forming cells. During the secretory stage the differentiated cells start to deposit the specific dental matrix and minerals. Once the dental hard tissue in the crown has been formed and completely calcified, tooth development continues with the root formation and tooth eruption.

Root formation takes place concomitantly with the development of the supporting structures of the teeth (periodontal ligament, cement, alveolar bone). The epithelial buds of the permanent teeth (except permanent molars) develop from the dental lamina of the primary teeth.

2 What are the stages of tooth eruption?

Eruption of teeth can be divided into different stages.

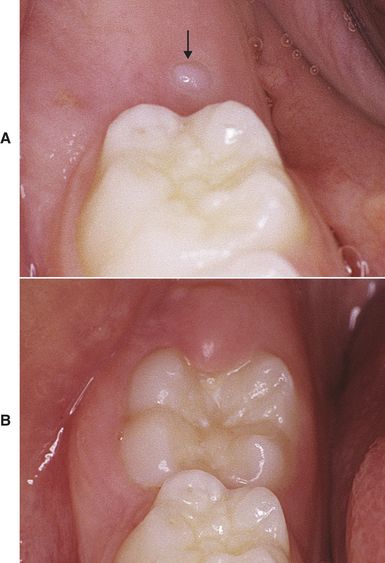

FIG 2-1 A, The mesiolingual cusp of the lower right first permanent molar (arrow) has emerged. B, Two months later the occlusal surface can be seen. Next, postemergent eruption follows and a tooth erupts until it reaches the occlusal level.

Recent studies have shown that short-term eruption of teeth follows day-night (circadian) rhythm.

3 What is the eruption timing and sequence of primary teeth?

There is a large individual variation in the eruption schedule of both primary and permanent teeth. Delay or acceleration of 6 months from the average eruption timetable is still within the normal range. Despite variation in the eruption schedule, the eruption sequence of teeth is usually preserved.

Generally the first primary teeth to erupt are the lower central incisors (on average at 7 months), followed soon by the upper central incisors (on average at 10 months). Thereafter, the upper and lower lateral incisors emerge (on average at 12 months), then the upper and lower first molars (on average at 16 months). Primary canines erupt on average at 20 months and finally the second molars on average at 28 months. Primary dentition is thus fully formed by the age of 2½ years with calcification of the roots of the primary teeth completed a year later (

TABLE 2-1 Average Eruption Timing and Sequence of Primary Teeth

| TOOTH | TIME (IN MONTHS) |

|---|---|

| Lower central incisors | 7 |

| Upper central incisors | 10 |

| Upper and lower lateral incisors | 12 |

| Upper and lower 1st molars | 16 |

| Upper and lower canines | 20 |

| Upper and lower 2nd molars | 28 |

4 What are typical features of primary dentition?

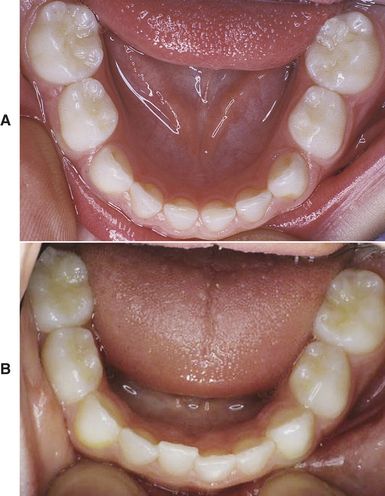

Spacing in the primary dentition is a typical feature and a requirement to secure space for the larger permanent incisors (

5 What is the terminal plane and what are the different terminal plane relationships in the primary dentition?

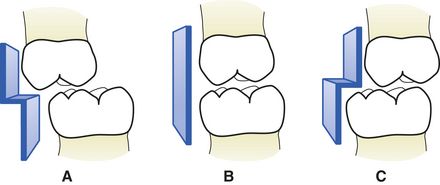

Terminal plane denotes the anteroposterior relationship (discrepancy) between the distal surfaces of the upper and lower second primary molars. It can be a flush terminal plane or there may be a mesial or a distal step (

FIG 2-3 Terminal plane denotes the anteroposterior relationship between the distal surfaces of the upper and lower second primary molars. In the Caucasian population about 60% of children exhibit mesial step (A), about 30% flush terminal plane (B), and about 10% distal step (C).

(From Bath-Balogh M, Fehrenbach MF: Illustrated dental embryology, histology, and anatomy, ed 2, St Louis, 2006, Saunders.)

6 What does the terminal plane relationship of the primary second molars predict on the permanent molar relationships?

The terminal plane relationship determines the anteroposterior position of the permanent first molars at the time of their eruption. Differential forward drift of the lower and upper first permanent molars (generally more forward drift of the lower molar) and differential maxillary and mandibular forward growth (generally more forward growth of the mandible) play a role in this transition. In about 80% of the individuals with mesial step less than 2 mm, Angle’s Class I molar relationship will result. If the mesial step is more than 2 mm, Class III molar relationship will result in 20% of the subjects. The flush terminal plane will result in either Class I (56% of subjects) or Class II (44% of subjects) molar relationship, depending on the amount of mandibular anterior growth and forward drift of the lower first primary molars in relation to the upper ones. Distal step of the primary second molars almost invariably results in a Class II molar relationship in the permanent dentition.

7 How is Angle’s classification of occlusion defined?

Angle’s original classification of occlusion is based on the anteroposterior relationship between the upper and lower first permanent molars. In Class I occlusion, the mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first molar occludes with the buccal groove of the lower first molar. Class I occlusion can further be divided into normal occlusion and malocclusion. Both subtypes have the same molar relationship but the latter is also characterized by crowding, rotations, and other positional irregularities.

Class II occlusion is when the mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first molar occludes anterior to the buccal groove of the lower first molar. Two subtypes of Class II occlusion exist. Both have Class II molar relationship, but the difference lies in the position of the upper incisors. In Class II division 1 malocclusion, the upper incisors are labially tilted, creating significant overjet. On the contrary, the upper central incisors are lingually inclined and the lateral incisors are labially inclined in Class II division 2 malocclusion. When measured from the first incisors, overjet is within normal limits in individuals with Class II division 2 malocclusion.

Class III malocclusion is opposite to Class II: the mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first molar occludes more posterior than the buccal groove of the lower first molar.

8 What is the eruption timing and sequence of permanent teeth?

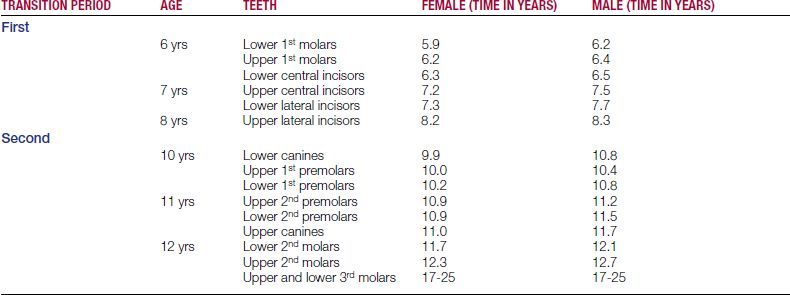

The eruption sequence can be checked with the help of eruption charts and is a useful tool for the orthodontist to assess the dental age of a patient (

Permanent teeth erupt in two different stages. The first transitional period occurs between the ages of 6 and 8 and is followed by approximately a 2-year intermediate period. The second transitional period starts on average at the age of 10 years and lasts around 2 years. In general, teeth erupt earlier in girls than in boys. As in the primary dentition, there is a great individual variation in the eruption timing of permanent teeth. Delay or acceleration of 12 months from the average eruption timetable is still within the normal range.

The first transitional period, between 6 and 8 years, can be divided further into three yearly stages. At 6 years the upper and lower first molars (also called 6-year molars) and the permanent lower central incisors erupt (

FIG 2-4 The first transitional period starts at approximately the age of 6 years with the eruption of the upper and lower first molars (A) and the lower central incisors (B).

The second transitional period can also be divided into three yearly stages. The first period is characterized by the eruption of the lower canines and lower and upper first premolars within the same time frame at about 10½ years of age. This is followed soon by the eruption of the upper and lower second premolars and usually somewhat later by the upper canines (at the age of 11 years). The second molars (12-year molars) complete the second transitional period at the age of 12 years.

Eruption of the third molars occurs much later with large individual variation (range, 17-25 years).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses