Special Considerations in Treatment for Adults

In contrast, the discussion of comprehensive treatment for adults in the latter part of Chapter 18 builds on the principles discussed in Chapters 14 to 16 and focuses on the aspects of comprehensive treatment for adults that are different from treatment for younger patients. Comprehensive orthodontics for adults tends to be difficult and technically demanding. The absence of growth means that growth modification to treat jaw discrepancies is not possible. The only possibilities are tooth movement for camouflage or orthognathic surgery, but applications of skeletal anchorage now are broadening the scope of orthodontics to include some patients who would have required surgery even a few years ago. Applications of skeletal anchorage are discussed and illustrated in detail in this chapter; a discussion of skeletal anchorage versus surgery follows in Chapter 19.

Goals of Adjunctive Treatment

Whatever the occlusal status originally, the goals of adjunctive treatment should be to:

1. Improve periodontal health by eliminating plaque-harboring areas and improving the alveolar ridge contour adjacent to the teeth.

2. Establish favorable crown-to-root ratios and position the teeth so that occlusal forces are transmitted along the long axes of the teeth.

3. Facilitate restorative treatment by positioning the teeth so that:

• Orthodontic treatment for temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) should not be considered adjunctive treatment.

• Although intrusion of teeth can be an important part of comprehensive treatment for adults, it probably should be managed by an orthodontist even as an adjunctive procedure because of the technical difficulties involved and the possibility of periodontal complications. As a general guideline in treatment of adults with periodontal involvement and bone loss, lower incisor teeth that are excessively extruded are best treated by reduction of crown height, which has the added advantage of improving the ultimate crown-to-root ratio of the teeth. For other teeth, tooth–lip relationships must be kept in mind when crown height reduction is considered.

• Crowding of more than 3 to 4 mm should not be attempted by stripping enamel from the contact surfaces of the anterior teeth. It may be advantageous to strip posterior teeth to provide space for alignment of the incisors, but this requires a complete orthodontic appliance and cannot be considered adjunctive treatment.

Principles of Adjunctive Treatment

Diagnostic and Treatment Planning Considerations

Nevertheless, the steps outlined in Chapter 6 should be followed when developing the problem list. The interview and clinical examination are the same whatever the type of orthodontic treatment. Diagnostic records for adjunctive orthodontic patients, however, differ in several important ways from those for adolescents and children.

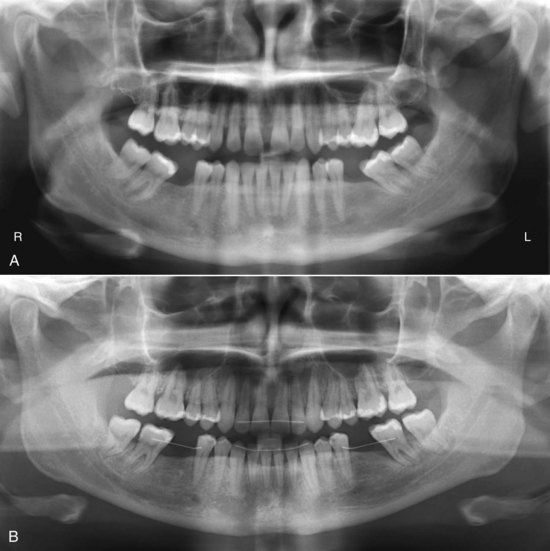

For this adult and dentally compromised population, the records usually should include individual intraoral radiographs to supplement the panoramic radiograph that often suffices for younger and healthier patients (Figure 18-1). When active dental disease is present, the panoramic radiograph does not give sufficient detail. The revised guidelines from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in late 2004 (see Table 6-5) should be followed in determining exactly what radiographs are required in evaluating the patient’s oral health status. The American Board of Orthodontics now requires evidence of pretreatment periodontal condition for all adult patients.1

For adjunctive orthodontics with a partial fixed appliance, pretreatment cephalometric radiographs usually are not required, but it is important to anticipate the impact of various tooth movements on facial esthetics. In some instances, the computer prediction methods used in comprehensive treatment (see Chapter 7) can be quite useful in planning adjunctive treatment. Articulator-mounted casts are likely to be needed because they facilitate the planning of associated restorative procedures.

Biomechanical Considerations

Characteristics of the Orthodontic Appliance

Recently, further developments in clear aligner therapy (CAT [see Chapter 10]) have provided an effective type of removable appliance that can be well suited to alignment of anterior teeth. Removable appliances of the traditional plastic-and-wire type are rarely satisfactory for adjunctive (or comprehensive) treatment. They often are uncomfortable and are likely to be worn for too few hours per day to be effective. With CAT, both discomfort and interference with speech and mastication are minimized, and patient cooperation improves. A fixed appliance on posterior teeth only is all but invisible, but it is quite apparent on anterior teeth, and the better appearance of a clear aligner also is a factor in choosing it to align anterior teeth.

Despite this esthetic advantage, there are biomechanical limitations. Control of root position is extremely difficult with clear aligners, and it also is difficult to correct rotations and to extrude teeth.2 If these limitations are not important in a particular adjunctive case, CAT can be considered. If they are, in nearly all cases adults who are candidates for adjunctive treatment will accept a lingual appliance or a visible fixed appliance.3

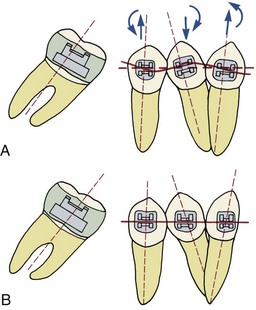

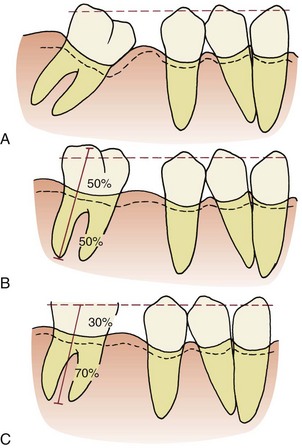

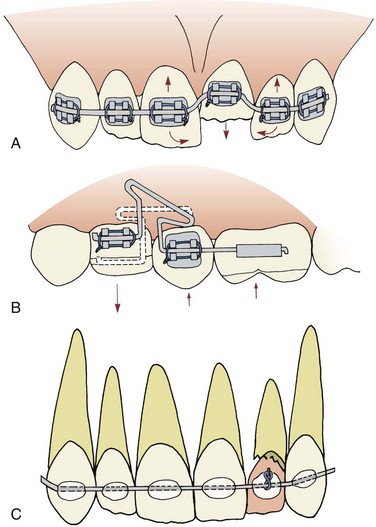

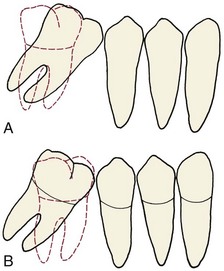

Modern edgewise brackets of the straight-wire type are designed for a specific location on an individual tooth. Placing the bracket in its ideal position on each tooth implies that every tooth will be repositioned if necessary to achieve ideal occlusion (Figure 18-2, A). Since adjunctive treatment is concerned with only limited tooth movements, usually it is neither necessary nor desirable to alter the position of every tooth in the arch. For this reason, in a partial fixed appliance for adjunctive treatment, the brackets are placed in an ideal position only on teeth to be moved, and the remaining teeth to be incorporated in the anchor system are bracketed so that the archwire slots are closely aligned (Figure 18-2, B). This allows the anchorage segments of the wire to be engaged passively in the brackets with little bending. Passive engagement of wires to anchor teeth produces minimal disturbance of teeth that are in a physiologically satisfactory position. This important point is illustrated in more detail in the sections on specific treatment procedures that follow.

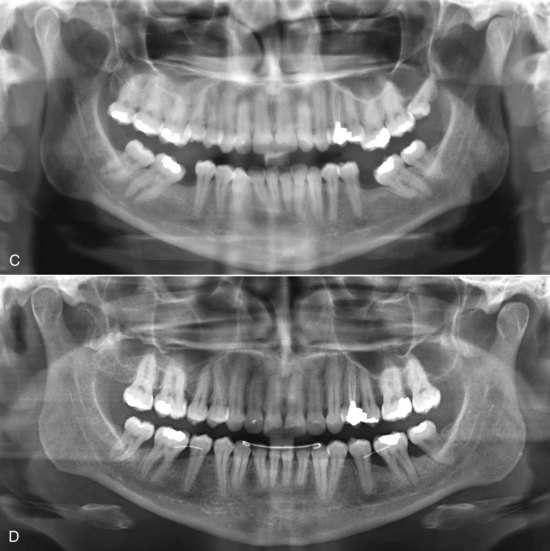

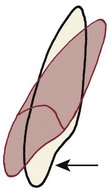

Effects of Reduced Periodontal Support

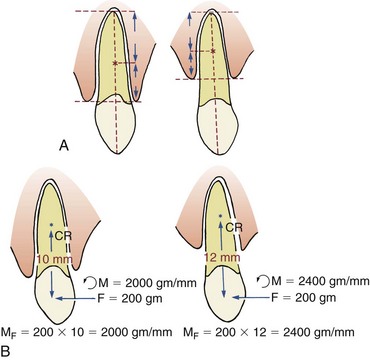

Since patients who need adjunctive orthodontic treatment often have lost alveolar bone to periodontal disease before it was brought under control, the amount of bone support of each tooth is an important special consideration. When bone is lost, the periodontal ligament (PDL) area decreases, and the same force against the crown produces greater pressure in the PDL of a periodontally compromised tooth than a normally supported one. The absolute magnitude of force used to move teeth must be reduced when periodontal support has been lost. In addition, the greater the loss of attachment, the smaller the area of supported root and the further apical the center of resistance will become (Figure 18-3). This affects the moments created by forces applied to the crown and the moments needed to control root movement. In general terms, tooth movement is quite possible despite bone loss, but lighter forces and relatively larger moments are needed.

Timing and Sequence of Treatment

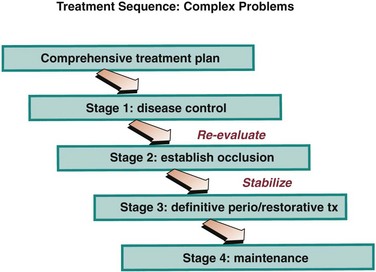

In the development of any orthodontic treatment plan, the first step is control of any active dental disease (Figure 18-4). Before any tooth movement, active caries and pulpal pathology must be eliminated, using extractions, restorative procedures, and pulpal or apical treatment as necessary. Endodontically treated teeth respond normally to orthodontic force, if all residual chronic inflammation has been eliminated.4 Prior to orthodontics, teeth should be restored with well-placed amalgams or composite resins. Restorations requiring detailed occlusal anatomy should not be placed until any adjunctive orthodontic treatment has been completed because the occlusion inevitably will be changed. This could necessitate remaking crowns, bridges, or removable partial dentures.

Periodontal disease also must be controlled before any orthodontics begins because orthodontic tooth movement superimposed on poorly controlled periodontal health can lead to rapid and irreversible breakdown of the periodontal support apparatus.5 Scaling, curettage (by open flap procedures, if necessary), and gingival grafts should be undertaken as appropriate. Surgical pocket elimination and osseous surgery should be delayed until completion of the orthodontic phase of treatment because significant soft tissue and bony recontouring occurs during orthodontic tooth movement. Clinical studies have shown that orthodontic treatment of adults with both normal and compromised periodontal tissues can be completed without loss of attachment, if there is good periodontal therapy both initially and during tooth movement.6

Adjunctive Treatment Procedures

Treatment Planning Considerations

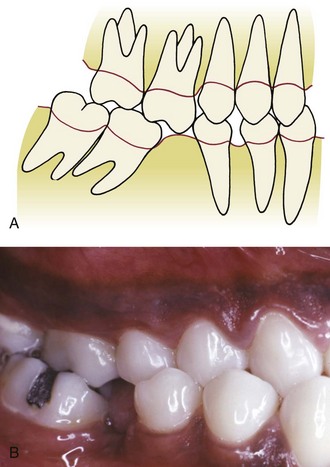

When a first permanent molar is lost during childhood or adolescence and not replaced, the second molar drifts mesially and the premolars often tip distally and rotate as space opens between them. As the teeth move, the adjacent gingival tissue becomes folded and distorted, forming a plaque-harboring pseudopocket that may be virtually impossible for the patient to clean (Figure 18-5). Repositioning the teeth eliminates this potentially pathologic condition and has the added advantage of simplifying the ultimate restorative procedures.

When molar uprighting is planned, a number of interrelated questions must be answered:

• If the third molar is present, should both the second and third molars be uprighted? For many patients, distal positioning of the third molar would move it into a position in which good hygiene could not be maintained or it would not be in functional occlusion. In these circumstances, it is more appropriate to extract the third molar and simply upright the remaining second molar tooth. If both molars are to be uprighted, a significant change in technique is required, as described below.

• How should the tipped teeth be uprighted? By distal crown movement (tipping), which would increase the space available for a bridge pontic or implant (Figure 18-6), or by mesial root movement, which would reduce or even close the edentulous space? As a general rule, treatment by distal tipping of the second molar and a bridge or implant to replace the first molar is preferred. If extensive ridge resorption has already occurred, particularly in the buccolingual dimension, closing the space by mesial movement of a wide molar root into the narrow alveolar ridge will proceed very slowly. If uprighting with space closure is to be done successfully, skeletal anchorage in the form of a temporary skeletal anchorage often is needed, and the treatment time is likely to be around 3 years (see Figure 18-37).

FIGURE 18-6 A, Uprighting a tipped molar by distal crown movement leads to increased space for a bridge pontic or implant, whereas uprighting the molar by mesial root movement (B) reduces space and might eliminate the need for a prosthesis, but this tooth movement can be very difficult and time-consuming to accomplish, especially if the alveolar bone has resorbed in the area where a first molar was extracted many years previously (see Figure 18-36).

• Is extrusion of a tipped molar permissible? Uprighting a mesially tipped tooth by tipping it distally, which leaves the root apex in its pretreatment position, also extrudes it. This has the merit of reducing the depth of the pseudopocket found on the mesial surface, and since the attached gingiva follows the cementoenamel junction while the mucogingival junction remains stable, it also increases the width of the keratinized tissue in that area. In addition, if the height of the clinical crown is systematically reduced as uprighting proceeds, the ultimate crown–root length ratio will be improved (Figure 18-7). Unless slight extrusion or crown–height reduction is acceptable, which usually is the case, the patient should be considered to have problems that require comprehensive treatment and treated accordingly.

• Should the premolars be repositioned as part of the treatment? This will depend on the position of these teeth and the restorative plan, but in many cases the answer is yes. It is particularly desirable to close spaces between premolars when uprighting molars because this will improve both the periodontal prognosis and long-term stability. In some instances, uprighting the molar and then moving the premolar back against it will provide a better site mesial to the premolar for an implant.

Appliances for Molar Uprighting

Where premolar and canine brackets should be placed depends on the intended tooth movement and occlusion. If these teeth are to be repositioned, the brackets should be placed in the ideal position at the center of the facial surface of each tooth. However, if the teeth are merely serving as anchor units and no repositioning is planned, then the brackets should be placed in the position of maximum convenience where minimum wire bending will be required to engage a passive archwire (see Figure 18-2).

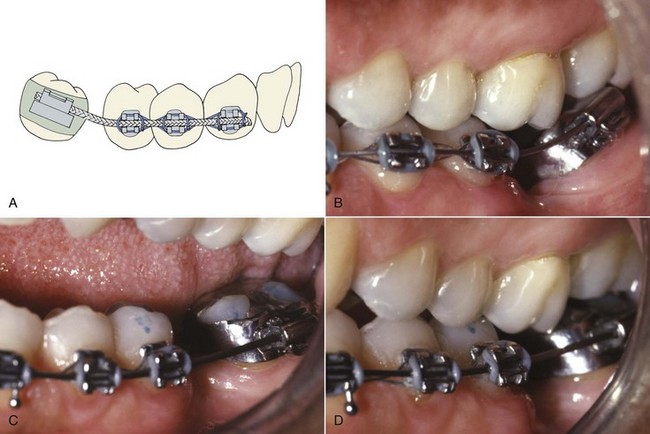

Distal crown tipping: If the molar is only moderately tipped, treatment often can be accomplished with a flexible rectangular wire. The best choice is 17 × 25 austenitic nickel–titanium (A-NiTi) that delivers approximately 100 gm of force (see Chapter 10). With this material, a single wire may complete the necessary uprighting (Figure 18-8). A braided rectangular steel wire also can be used but is more likely to require removal and reshaping. It is important to relieve the occlusion as the tooth tips upright. Failure to do this may cause excessive tooth mobility and increases treatment time.

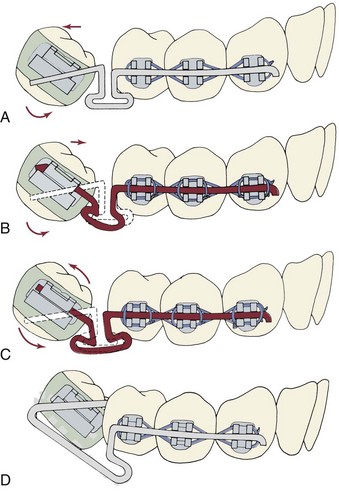

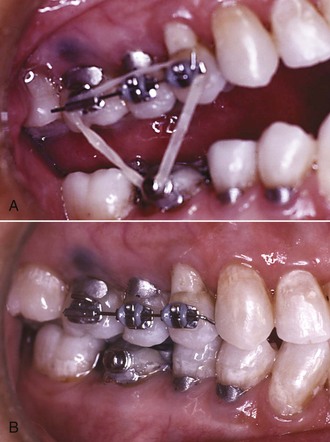

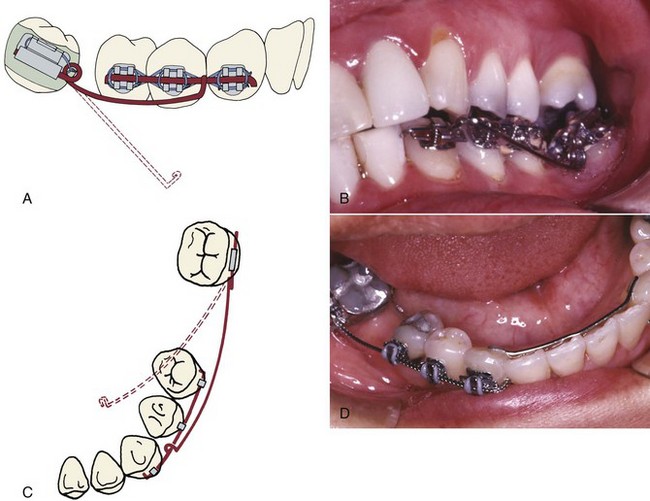

If the molar is severely tipped, a continuous wire that uprights the molar will have side effects (which almost always are undesirable) on the position and inclination of the second premolar. For that reason it is better to carry out the bulk of the uprighting using a sectional uprighting spring (Figure 18-9). After preliminary alignment of the anchor teeth if necessary, stiff rectangular wire (19 × 25 steel) maintains the relationship of the teeth in the anchor segment, and an auxiliary spring is placed in the molar auxiliary tube. The uprighting spring is formed from either 17 × 25 beta-Ti wire without a helical loop or 17 × 25 steel wire with a loop added to provide more springiness. The mesial arm of the helical spring should be adjusted to lie passively in the vestibule and upon activation should hook over the archwire in the stabilizing segment. It is important to position the hook so that it is free to slide distally as the molar uprights. In addition, a slight lingual bend placed in the uprighting spring is needed to counteract the forces that tend to tip the anchor teeth buccally and the molar lingually (Figure 18-9, C).

FIGURE 18-9 Uprighting with an auxiliary spring. A, If the relative alignment of the molar precludes extending the stabilizing segment into the molar bracket, then a rigid stabilizing wire, 19 × 25 stainless steel, is placed in the premolars and canine only (often with the brackets positioned so this wire is passive—see Figure 18-2). The mesial arm of the uprighting spring lies in the vestibule before engagement, and the spring is activated by lifting the mesial arm and hooking it over a stabilizing wire in the canine and premolar brackets. B, Auxiliary uprighting spring to molar just after initial placement. Note the helix bent into the steel wire that forms the spring to provide better spring qualities. C, Because the force is applied to the facial surface of the teeth, an auxiliary uprighting spring tends not only to extrude the molar but also to roll it lingually, while intruding the premolars and flaring them buccally. To counteract this side effect, the uprighting spring should be curved buccolingually so that when it is placed into the molar tube, the hook would lie lingually to the archwire prior to activation (dotted line). D, Better control of anchorage, with either a continuous wire or an auxiliary spring, is obtained when a canine-to-canine stabilizing wire is bonded on the lingual surface of these teeth.

Mesial root movement: If a mesial root movement is desired, an alternative treatment approach is indicated. Skeletal anchorage is required if the goal is to close the old extraction space (see Figure 18-36). If a small amount of mesial movement to prevent opening too much space is the goal, a single “T-loop” sectional archwire of 17 × 25 stainless steel or 19 × 25 beta-titanium (beta-Ti) wire can be effective (Figure 18-10). After initial alignment of the anchor teeth with a light flexible wire, the T-loop wire is adapted to fit passively into the brackets on the anchor teeth and gabled at the T to exert an uprighting force on the molar. Insertion into the molar can be from the mesial or distal. If the treatment plan calls for maintaining or closing rather than increasing the pontic space, the distal end of the archwire should be pulled distally through the molar tube, opening the T-loop by 1 to 2 mm, and then bent sharply gingivally to maintain this opening. This activation provides a mesial force on the molar that counteracts distal crown tipping while the tooth uprights (Figure 18-10, D). If opening the space is desired, the end of the wire is not bent over so the tooth can slide distally along it.

Final positioning of molar and premolars: Once molar uprighting is almost complete, often it is desirable to increase the available pontic space and close open contacts in the anterior segment. This is done best using a relatively stiff base wire, with a compressed coil spring threaded over the wire to produce the required force system. With 22-slot brackets, the base wire should be 18 mil round or 17 × 25 rectangular steel wire, which should engage the anchor teeth and the uprighted molar more or less passively. The wire should extend through the molar tube, projecting about 1 mm beyond the distal. An open coil steel spring (.009 wire, .030 lumen) is cut so that it is 1 to 2 mm longer than the space, slipped over the base wire (Figure 18-11), and compressed between the molar and distal premolar. It should exert a force of approximately 150 gm to move the premolars mesially while continuing to tip the molar distally. The coil spring can be reactivated without removing it by compressing the spring and adding a split stop to maintain the compression (Figure 18-11, B).

Uprighting Two Molars in the Same Quadrant

Because the resistance offered when uprighting two molars is considerable, only small amounts of space closure should be attempted. Unless comprehensive orthodontics with a complete fixed appliance is planned, the goal should be a modest amount of distal crown tipping of both teeth, which typically would leave space for a premolar-sized implant or pontic. In the lower arch, a bonded canine-to-canine lingual stabilizing wire (which is similar to a bonded retainer) is needed to control the position of the anterior teeth (see Figure 18-9, D). Trying to upright both the second and third molars bilaterally at the same time is not a good idea—significant movement of the anchor teeth is inevitable unless skeletal anchorage is used.

Retention

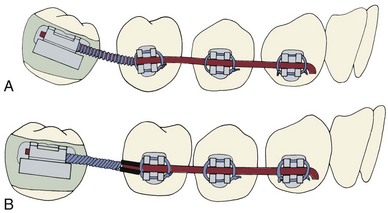

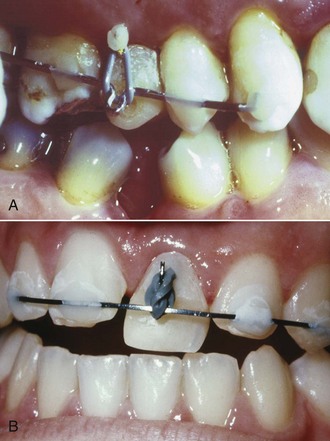

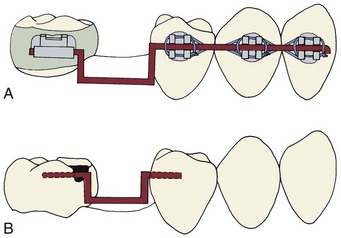

After molar uprighting, the teeth are in an unstable position until the prosthesis that provides the long-term retention is placed. Long delays in making the final prosthesis should be avoided if possible. As a general guideline, a fixed bridge can and should be placed within 6 weeks after uprighting is completed. Especially if an implant is planned, there may be a considerable delay while a bone graft heals and the implant becomes integrated. If retention is needed for more than a few weeks, the preferred approach is an intracoronal wire splint (19 × 25 or heavier steel wire) bonded into shallow preparations in the abutment teeth (Figure 18-12). This type of splint causes little gingival irritation and can be left in place for a considerable period, but it would have to be removed and rebonded to allow bone grafting and implant surgery.

FIGURE 18-12 A molar that has been uprighted is unstable and must be maintained in its new position until a fixed bridge or implant is placed to stabilize it. There are two ways to provide temporary stabilization: A, A heavy rectangular (19 × 25) steel wire engaging the brackets passively and (B) an intracoronal splint (often called an A-splint) made with 19 × 25 or 21 × 25 steel wire that is bonded in shallow preparations in the proximal enamel with composite resin (see also Figure 17-14). This causes minimal tissue disturbance. The intracoronal splint is preferred, particularly if retention is to be continued for more than a few weeks.

Crossbite Correction

Posterior crossbites frequently are corrected using “through the bite” elastics from a conveniently placed tooth in the opposing arch, which moves both the upper and lower tooth (Figure 18-13, A). This tips the teeth into the correct occlusion but also tends to extrude them. For this reason, elastics must be used with caution to correct posterior crossbites in adults because the extrusion can change occlusal relationships throughout the mouth. One way to obtain more movement of a maxillary tooth than its antagonist in the lower arch is to have several teeth in the lower arch stabilized by a heavy archwire segment (Figure 18-13, B to D). Of course, the same approach could be used in reverse to produce more movement of a mandibular tooth. If a mesially tipped lower molar also is in buccal crossbite, an auxiliary uprighting spring can move it lingually as it uprights by two modifications in design: omitting the inward bending of the spring before it is activated (see Figure 18-9, C) and making the spring from round wire.

If an anterior crossbite is due only to a displaced tooth and if correcting it requires only tipping (as perhaps in the case of a maxillary incisor that was tipped lingually into crossbite), then a removable appliance or clear aligner may be used to tip the tooth into a normal position. However, when using either type of removable appliance, tipping a tooth facially or lingually also produces a vertical change in occlusal level (Figure 18-14). Tipping maxillary incisors labially to correct anterior crossbite nearly always produces an apparent intrusion and a reduction in overbite. This can present a problem during retention, since a positive overbite serves to retain the crossbite correction. A fixed appliance generally is necessary for vertical control in correction of anterior crossbites.

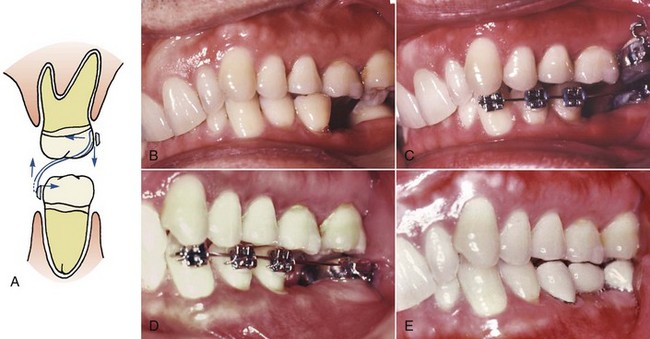

Extrusion

For teeth with defects in or adjacent to the cervical third of the root, controlled extrusion (sometimes called forced eruption) can be an excellent alternative to extensive crown-lengthening surgery.7 Extruding the tooth can allow isolation under a rubber dam for endodontic therapy when it would not be possible otherwise. Extrusion also allows crown margins to be placed on sound tooth structure while maintaining a uniform gingival contour that provides improved esthetics (Figure 18-15). In addition, the alveolar bone height is not compromised, the apparent crown length is maintained, and the bony support of adjacent teeth is not compromised. As the tooth is extruded, the attached gingiva should follow the cementoenamel junction. This returns the width of the attached gingiva to its original level. However, it usually is necessary to perform some limited recontouring of the gingiva, and often of the bone, to produce a contour even with the adjacent teeth and a proper biologic width.

Orthodontic Technique

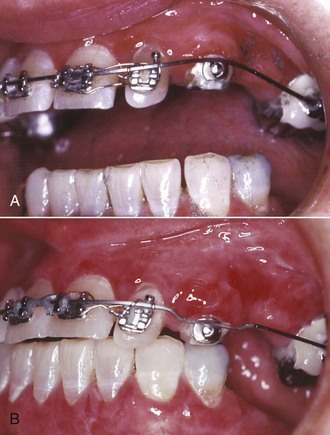

Since extrusion is the tooth movement that occurs most readily and intrusion is the movement that occurs least readily, ample anchorage is usually available from adjacent teeth. The appliance needs to be quite rigid over the anchor teeth, and flexible where it attaches to the tooth that is being extruded. A continuous flexible archwire (see Figure 18-15) produces the desired extrusion but must be managed carefully because it also tends to tip the adjacent teeth toward the tooth being extruded, reducing the space for subsequent restorations and disturbing the interproximal contacts within the arch (Figure 18-16, A). A flexible cantilever spring to extrude a tooth (Figure 18-16, B), or a rigid stabilizing wire and an auxiliary elastomeric module or spring for extrusion (Figure 18-16, C) provide better control.

Two methods are suggested for extrusion in uncomplicated cases. The first employs a stabilizing wire, 19 × 25 or 21 × 25 stainless steel, bonded directly to the facial surface of the adjacent teeth (Figure 18-17). A post and core with temporary crown and pin is placed on the tooth to be extruded, and an elastomeric module is used to extrude the tooth. This appliance is simple and provides excellent control of anchor teeth, but better control can be obtained when orthodontic brackets are used.

The alternative is to bond brackets to the anchor teeth, bond an attachment (often a button rather than a bracket) to the tooth to be extruded, and use interarch elastics (Figure 18-18) or a flexible archwire (Figure 18-19). If the buccal surface of the tooth to be extruded is intact, a bracket should be bonded as far gingivally as possible.

With any technique for controlled extrusion, the patient must be seen every 1 to 2 weeks to remove any occlusal contacts that would impede eruption (for instance, shorten the height of a temporary crown) if this is needed (see Figure 18-17), control inflammation, and monitor progress. After active tooth movement has been completed, at least 3 weeks but not more than 6 weeks of stabilization is needed to allow reorganization of the PDL. If periodontal surgery is needed to recontour the alveolar bone and/or reposition the gingiva, it can be done a month after completion of extrusion. As with molar uprighting, it is better to complete the definitive pros/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses