Chapter 18

Malignant lesions

This chapter focuses on the imaging of malignant lesions arising in bone or soft tissue structures of the skull and aerodigestive tract. Ninety percent of such malignant lesions are squamous cell carcinomas arising from the oral cavity or pharynx; these are dealt with at the end of the chapter.

Malignant Lesions Affecting the Bones of the Skull Base

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

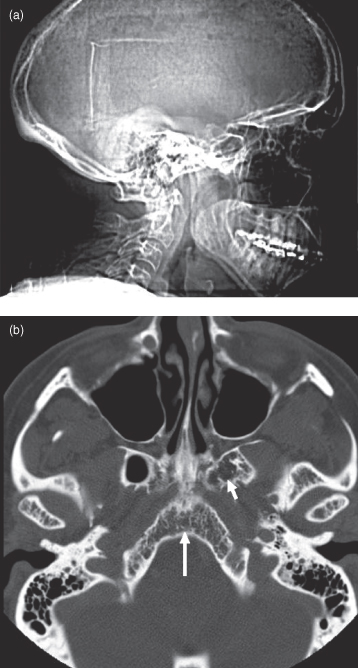

Multiple myeloma, introduced in Chapter 9, is a malignancy of plasma cells found in bone marrow and lymphatics. It occurs in older people and in North America it is approximately twice as common in African-Americans as in Caucasians (3–10 cases per 100,000). This disease most commonly has a widespread distribution through the bone marrow cavities though occasionally can present as a solitary lesion (solitary plasmacytoma). It is the most common primary bone tumor affecting the cranial vault. Myeloma in the calvarium will cause punched-out lucent lesions. These, in advanced cases, lead to a salt-and-pepper appearance. On CT there will be loss of the trabecular pattern in the marrow space (Figure 18.1).1

Figure 18.1. Multiple myeloma affecting the skull. (a) Lateral projection of the skull. Note the salt-and-pepper appearance of the cranial vault produced by numerous myelomatous deposits. (b) Axial CT (bone window). Note the focal loss of bony trabeculae within the clivus (long arrow) and the left basal pterygoid plate (short arrow).

CHORDOMA

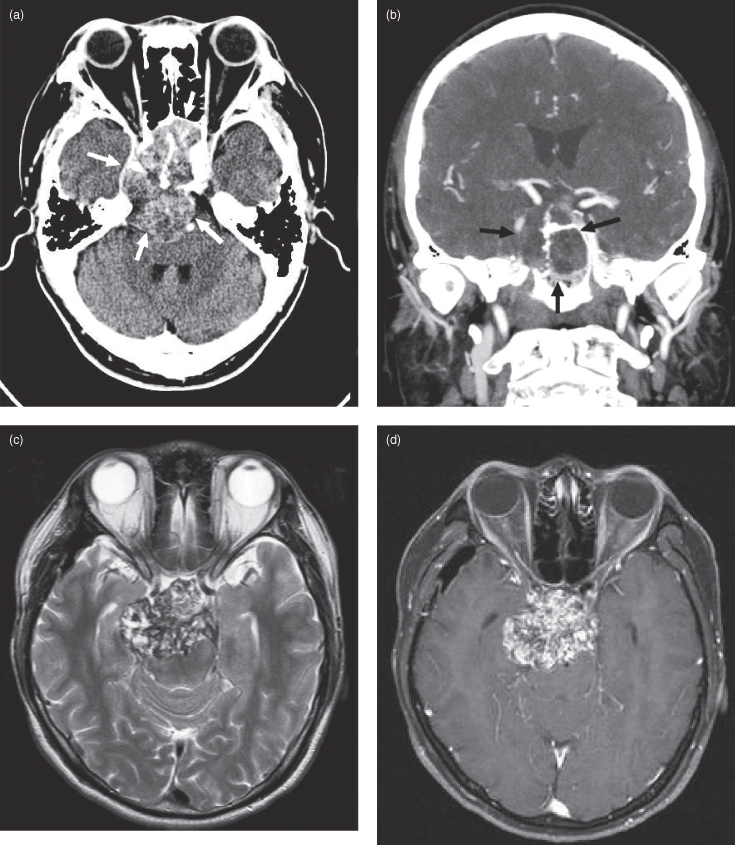

Chordomas are rare, slowly expansile malignant neoplasms thought to arise from embryonic notochord remnants. They can occur anywhere in the axial skeleton. Thirty-five percent arise in the skull base, predominantly in the midline and usually involving the clivus and/or dorsum sellae.2 The average age at diagnosis is approximately 50 years. Chordomas rarely metastasize and are locally aggressive, producing symptoms from cranial nerve compression and destruction of local skull base structures.3 As such, these patients often present with diplopia due to third and sixth nerve involvement.4 On computed tomography (CT) chordomas are seen as lobulated midline mass lesions, often with flecks of internal calcification (Figure 18.2a,b). On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) they are hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Figure 18.2c) with heterogeneous enhancement on postgadolinium sections5 (Figure 18.2d).

Figure 18.2. Computed tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging MRI of chordoma. (a) An axial postcontrast CT (soft-tissue window) of a well-defined chordoma destroying the clivus and extending anteriorly to fill the sphenoid sinus and abut posterior ethmoid air cells (arrows). Posteriorly the lesion grossly indents the brainstem and displaces the basilar artery to the left. (b) Coronal postcontrast CT (soft-tissue window) of the same lesion in (a) expanding the sphenoid sinus and destroying the right lateral wall (arrows). The condylar heads and odontoid process are displayed. The arteries exhibit greater enhancement than the right jugular vein. (c) An axial T2-weighted MRI at the level of the optic nerve traversing the optic canal, displaying a heterogeneous, well-defined chordoma centered in the dorsum sellae. It is expanding into the left temporal lobe and the midbrain. The optic chiasm is not seen since it is displaced superiorly. d) An axial postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI at a level near (c). (e) Sagittal postgadolinium T1-weighted fat-saturated MRI showing a well-defined lobulated lesion destroying the clivus and extending anteriorly over the dorsum sellae into the pituitary fossa. It has also expanded posteriorly against the midbrain and pons. (f) Coronal fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI of the same lesion.

OSTEOSARCOMA AND CHONDROSARCOMA

Osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma (introduced in Chapter 10) are the first and second, respectively, most frequent malignant tumors of bone. Despite this, extragnathic osteosarcoma affecting the skull base or vault is very rare; reported cases are often radiation-induced.6,7 Imaging findings in the skull are similar to those in the jaws.

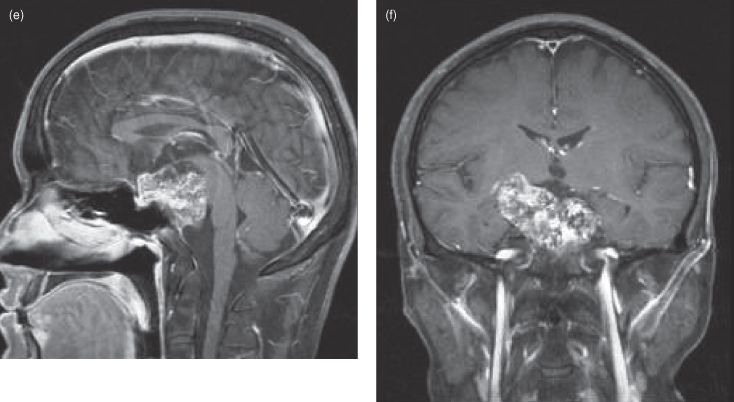

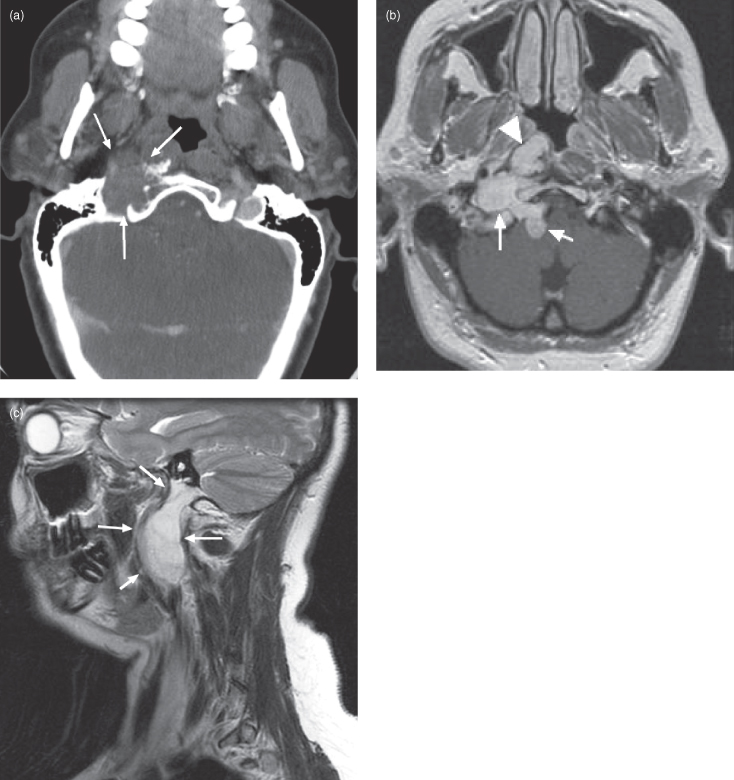

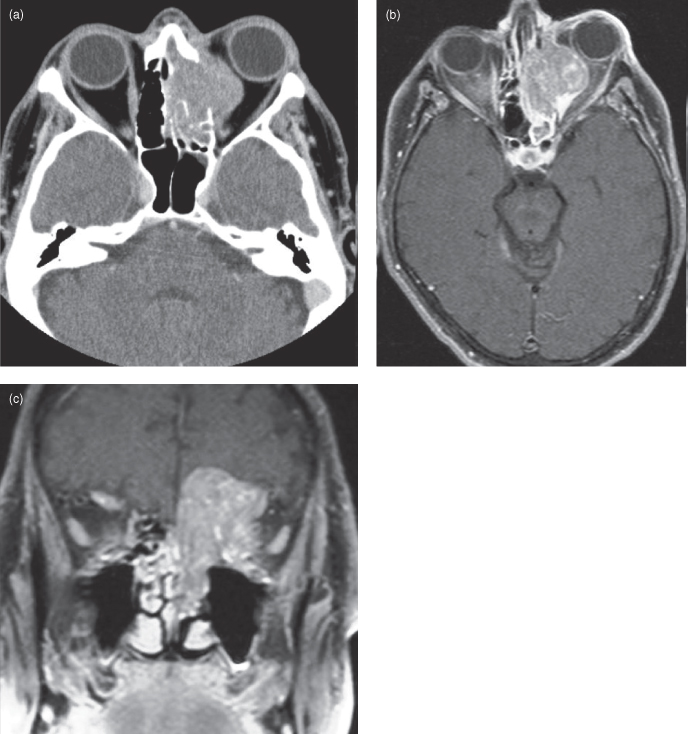

Chondrosarcomas of the skull base most often arise at synchondroses between membranous bones; especially in the petroclival fissure (Figure 18.3). In contrast to chordomas that occur in the midline, these tumors arise in a paramedian position. Lower-grade lesions expand locally producing cranial nerve deficits much like those caused by chordomas. The higher-grade lesions rarely metastasize, but if they do, it is usually to the lungs. Chondrosarcomas can also occur in the cavernous sinus, superior midline nasal septum, and laryngeal cartilage (Figure 18.4).8–10 They are composed of chondroid matrix; hence on CT they often contain an irregular lattice of internal calcification. Chondrosarcomas are well-circumscribed lobulated tumors that exhibit low to isointense T1-weighted signals, hyperintense T2-weighted signals, and heterogeneous enhancement on MRI.

Figure 18.3. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a right petroclival fissure chondrosarcoma. (a) Axial postcontrast CT (soft-tissue window) displaying a well-defined chondrosarcoma centered in the right petroclival fissure, eroding into the right inferolateral clivus and expanding laterally into the jugular foramen. This is a typical location for this tumor. (b) Axial T1-weighted MRI of the same patient in (a). The lesion (white arrows) has traveled posteriorly through the right jugular foramen into the posterior cranial fossa and has extended anteromedially into the right fossa of Rosenmuller (white arrowhead). (c) A sagittal T1-weighted MRI displaying inferior extension of the lesion through the jugular foramen and down the jugular sheath.

Figure 18.4. An axial postcontrast computed tomography (CT) (soft-tissue window). Low-grade chondrosarcoma involving the right thyroid cartilage of the larynx. The lesion does not enhance but has a hypodense center, suggestive of necrosis.

OLFACTORY NEUROBLASTOMA

Olfactory neuroblastoma (esthesioneuroblastoma) is a malignant tumor arising from olfactory epithelium in the nasal vault; most commonly at the cribriform plate. It is an uncommon lesion, comprising 3% of all intranasal tumors11 and 5–6% of malignant nasal masses. It most often presents with symptoms of unilateral nasal obstruction with or without epistaxis. Due to initial lack of severe symptomatology these tumors present late and are often large at the time of diagnosis. Radiologically these lesions will traverse the cribriform plate, forming an intracranial component.12 On CT and MRI they vividly enhance, filling one or both sides of the nasal cavity. They are locally invasive (Figures 18.5, 18.6) and will rarely metastasize to retropharyngeal nodes.13

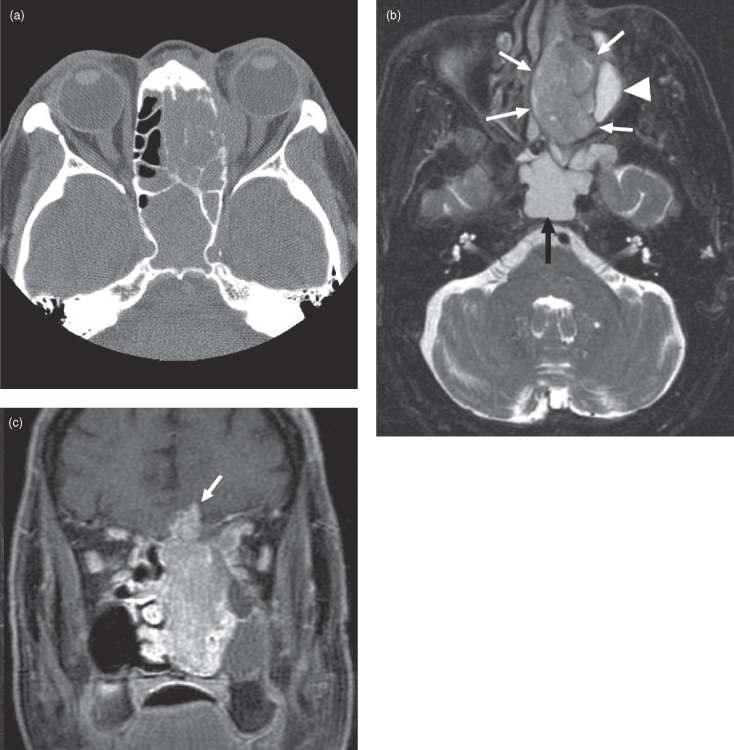

Figure 18.5. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of an olfactory neuroblastoma involving the left nasal cavity, ethmoid air cells and orbit. (a) Axial CT (bone window) at mid orbital level showing opacification of the left ethmoid air cells. The bony left ethmoid sinus is partially destroyed. Tumor has extended through the medial wall of the left orbit to elevate the left medial rectus muscle and produce mild proptosis. (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI at the level of the superior orbital cavity displays a well-defined mildly lobulated isointense lesion centered in the left nasal cavity (white arrows). Just posterior to the mass is a fluid-filled sphenoid sinus showing high T2 signal (black arrow). Another small fluid collection is seen lateral to the mass (white arrowhead). (c) Coronal postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI displaying a lobulated enhancing mass filling the left nasal cavity and ethmoid air cells. It is expanding laterally into the orbit and maxillary antrum. Tumor is extending through the cribriform plate to indent the olfactory gyrus of the left frontal lobe (arrow).

Figure 18.6. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of an olfactory neuroblastoma centered in the nasal cavity and extending upward through the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. (a) Axial CT (bone window) showing involvement of the ethmoid air cells. (b) Axial postgadoliniun fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI showing enhancement of the neuroblastoma. The nonenhancing posterior part consists of proteinacious fluid. (c) Coronal postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI showing the neuroblastoma. Note that the mucosa of both antral floors and of the inferior concha are thickened and hyperintense, suggesting that they are inflamed.

NASAL LYMPHOMA

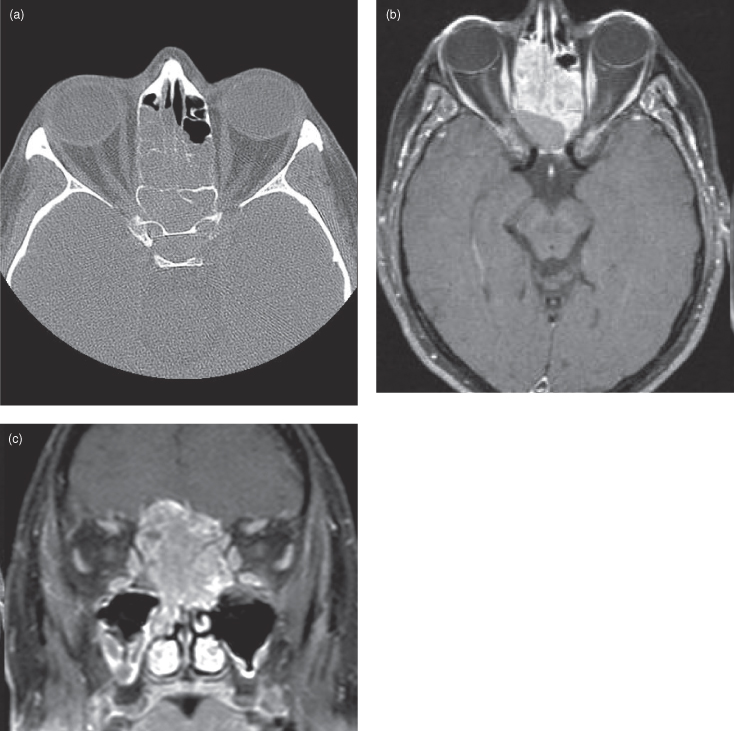

Primary nasal lymphoma is more frequent in East Asians, being quite rare in Caucasians. The most common subtype is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Figure 18.7), followed by T-cell natural killer (T/NK).14 It is mentioned here to point out that lymphoma can mimic many different types of tumors in different parts of the body, and the nasal cavity is no exception. Note the similarity to both olfactory neuroblastoma (see Figure 18.5, 18.6), and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (Figure 18.8). This tumor can also mimic the far more common squamous cell cancer, which also has a high prevalence in East Asians.

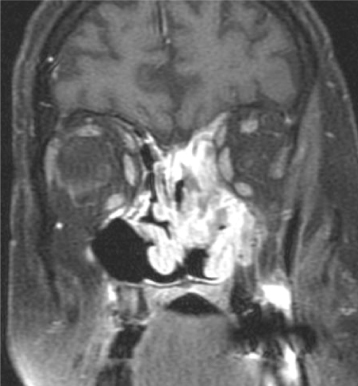

Figure 18.7. Coronal postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of a large B-cell lymphoma affecting the left nasal cavity, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses.

Figure 18.8. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC) invading the base of the skull. (a) Axial CT (soft-tissue window) showing a soft-tissue mass obliterating the right ethmoid air cells. The SNUC has destroyed much of the lateral wall of the nose and has invaded the medial aspect of the orbital cavity. The right eye now exhibits proptosis. (b) Axial postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI reveals mildly heterogeneous enhancement though the SNUC. The involvement of the orbital cavity is more marked and the eye displays more proptosis. (c) Coronal postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI reveals enhancement throughout the SNUC. Extensive invasion of the right orbit with encasement of the medial orbital muscles and destruction of the floor of the anterior cranial fossa is obvious. The tumor is compressing the inferior part of the left frontal lobe.

SINONASAL UNDIFFERENTIATED CARCINOMA (SNUC)

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC) is a bad actor. This extremely malignant neoplasm grows rapidly and metastasizes early (Figure 18.8). It has a poor prognosis despite aggressive multimodality therapy.15–17. Histologically it is a neuroendocrine carcinoma, belonging to the same group as olfactory neuroblastoma. SNUC accounts for approximately 3% of upper aerodigestive tumors and most often occurs in the nasal cavity. As such, it often exhibits intracranial and orbital invasion when diagnosed.15,18 The symptoms it produces at presentation are common to other sinonasal diseases (nasal obstruction, unilateral pain, epistaxis). On CT and MRI, these tumors look similar to squamous cell cancer; an enhancing locally destructive mass.

MALIGNANT SALIVARY GLAND NEOPLASMS

Malignant salivary gland neoplasms can be divided into epithelial and nonepithelial tumors. The epithelial neoplasms can be further subdivided into carcinomas that differentiate toward acinar, ductal, myoepithelial, or mixed cell types; low- or high-grade adenocarcinomas; and carcinomas arising from benign mixed tumors (malignant mixed tumors). In most series, mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common epithelial salivary carcinoma19,20 followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma. Other common types of salivary gland carcinomas include acinic cell carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. There are a host of other rare carcinomas including basal cell, clear cell, cystadenocarcinoma, oncocytic, mucinous, salivary duct, sebaceous, squamous, adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), myoepithelial, epimyoepithelial, and small and large cell undifferentiated tumors (see later in this chapter). Malignant mixed tumors include carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma and carcinosarcoma. Nonepithelial tumors include various types of lymphomas and mesenchymal neoplasms, such as malignant schwannomas, fibrosarcomas, et cetera. This classification scheme follows that put forth by Ellis at the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP).21 The reader should be aware that there is some variation in the literature regarding nomenclature and classification of salivary gland tumors. For instance, many adenocarcinomas will also commonly be called carcinomas. Adenocarcinoma NOS is a catchall classification for those salivary malignancies that show ductal or glandular differentiation but cannot be easily placed in a specific category. The most common tumors will be described here. In general, the relative incidence of salivary gland malignancy is inversely proportional to the size of the gland with the highest frequency of malignancy found in the minor glands.

MUCOEPIDERMOID CARCINOMA

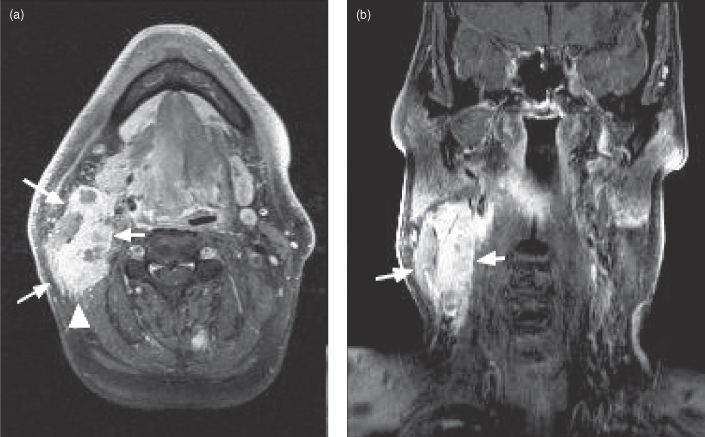

Mucoepidermoid carcinomas (MEC) are distributed equally between major and minor salivary glands.22 In the major salivary glands, MEC most commonly occurs in the parotid.23 In the minor salivary glands this tumor vies with adenoid cystic carcinoma for the most frequent malignant neoplasm.24 The average age at diagnosis is 56 years with an age range between 13 and 85 years. MEC occurs sporadically but is also associated with prior exposure to therapeutic ionizing radiation.25 Histologically, MEC contains multiple cellular elements including squamous and mucin-secreting cells. The latter cell type accounts for its inhomogeneous enhancement on CT and MRI. Low-grade tumors present as a well-defined heterogeneous mass with sharp margins, low T1-weighted and low T2-weighted signals. Higher-grade—i.e., more malignant—MECs exhibit less well-defined borders with greater enhancement (Figure 18.9).

Figure 18.9. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) of the right parotid gland. (a) Axial postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI showing a right parotid MEC (arrows). Note how the posterior border is less well defined, suggestive of a high-grade lesion (arrowhead). (b) Coronal postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI of the same patient in (a).

ADENOID CYSTIC CARCINOMA

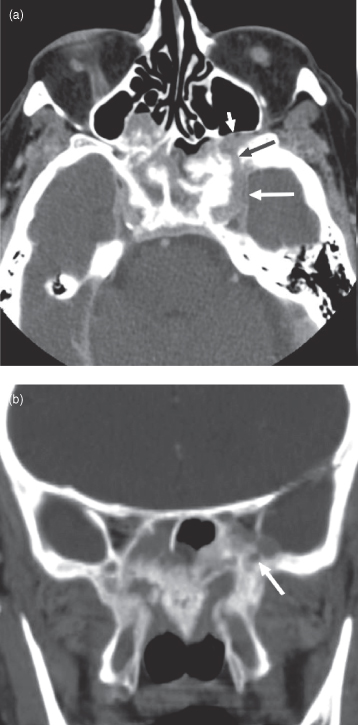

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a slow-growing, insidious, locally invasive tumor. On CT it presents as an enhancing mass, sometimes with adjacent bone erosion (Figure 18.10). On MRI the tumor is usually seen as a T1-weighted hypointense, mildly T2-weighted hyperintense lesion that moderately enhances (see Figure 18.11). These characteristics are not specific and are also seen in other head and neck neoplasms. Lower grade tumors are often well circumscribed and high grade lesions tend to have a poorly defined border. The mean age at diagnosis is 50 years and like mucoepidermoid carcinoma there is a wide age range (13–89 years).26

Figure 18.10. Computed tomography (CT) of adenoid cystic carcinoma arising within the sphenoid sinus producing neural foraminal widening and a permeative bone pattern. (a) An axial postcontrast CT through the roof of the orbit showing obliteration of the sphenoid sinus with bone destruction with invasion of adjacent structures. Tumor is seen traveling through foramen rotundum (black arrow) and the left cavernous sinus (white arrow), dilating the former structure. (b) A coronal CT bone window, at the level of the pterygoid plates, showing extensive pterygoid and mid-sphenoid permeative infiltration with tumor. The white arrow points to a mildly enlarged left foramen rotundum; its fellow is also enlarged.

Figure 18.11. Postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of adenoid cystic carcinoma arising in the right fossa of Rosenmuller. (a) Adenoid cystic carcinoma producing a right fossa of Rosenmuller mass (arrow). This is similar to the far more common squamous cell cancer seen here. The lesion is compressing the Eustachian tube, causing the right mastoid air cells to fill with fluid and become inflamed. (b) Coronal section from the same patient. Tumor is extending superiorly from the right fossa of Rosenmuller (oblique arrow) through foramen ovale (vertical arrow).

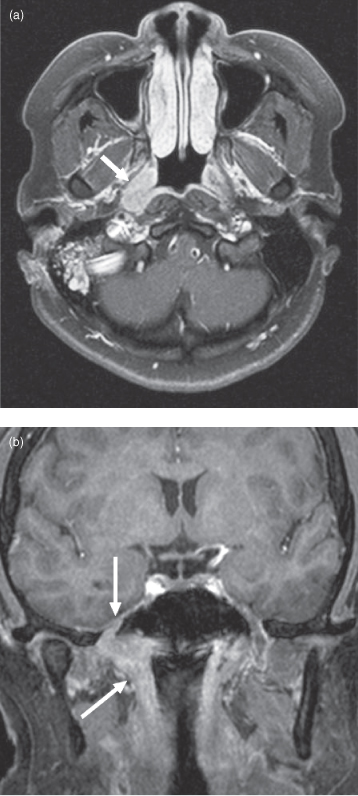

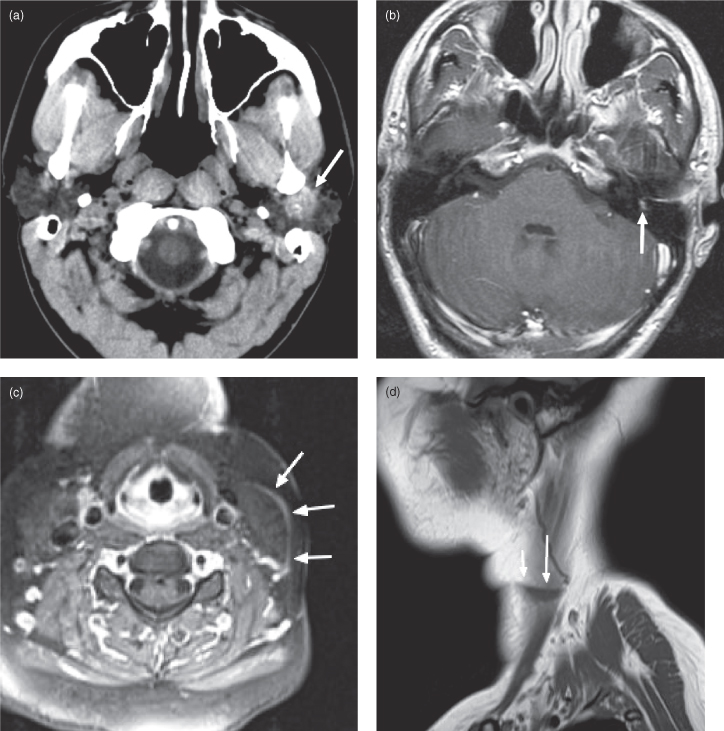

One particularly bad behavior of adenoid cystic is perineural spread; this is seen in 69% of cases and is associated with increased treatment failures.26,27 Perineural spread is diagnosed on CT via widening of associated neural foramina (Figure 18.10) and on MRI as postgadolinium enhancement within foramina (Figures 18.11b, 18.12b).28 These findings are often subtle and due to a high pretest probability, a pathologic diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma should prompt careful radiologic examination of all neural foramina associated with cranial nerves that pass through or nearby the lesion. MRI is currently the best modality for this; reaching a sensitivity of 95%.29 Imaging detection of perineural spread is important because 30–45% of perineural invasion is clinically asymptomatic30 and the presence of perineural spread correlates with a decreased 5-year survival rate.31 Radiation oncologists will also try to include visible regions of perineural spread in their treatment plan. Perineural spread is also seen with squamous cell carcinoma and occurs much less frequently with other head and neck neoplasms.

Figure 18.12. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of adenoid cystic carcinoma showing perineural spread. (a) Axial CT (soft tissue window) showing an adenoid cystic carcinoma arising in the left parotid gland (arrow). (b) Axial postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI of same patient as (a). Abnormal enhancement is present in the geniculate ganglion of the left facial nerve (arrow) due to retrograde perineural spread from tumor invading the facial nerve within the left parotid gland. (c) Axial postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI of a different patient showing perineural spread of adenoid cystic carcinoma along the left lateral cutaneous nerve (arrows). The original lesion was in the left submandibular gland; this was excised and the tumor recurred in the latter nerve. d) Sagittal noncontrast T1-weighted MRI showing a thickened lateral cutaneous nerve from adenoid cystic carcinoma perineural spread.

ACINIC CELL CARCINOMA

Acinic cell carcinomas are unusually slow-growing neoplasms containing clusters of cells with serous acinar differentiation. The mean age at diagnosis is 52 years.32 The majority occur in the parotid gland (86%),33 and acinic cell carcinoma is the most common malignant salivary neoplasm to present bilaterally (3% of cases34). On CT and MRI, the appearance is nonspecific, similar to other small benign (and some malignant) salivary gland tumors (Figure 18.13). Diagnosis is usually obtained by fine needle aspiration biopsy.

Figure 18.13. Axial postcontrast computed tomography (CT) (soft-tissue window). Acinic cell carcinoma of the left parotid gland. Note the mild rim enhancement (arrow).

OTHER RARE MALIGNANT SALIVARY NEOPLASMS

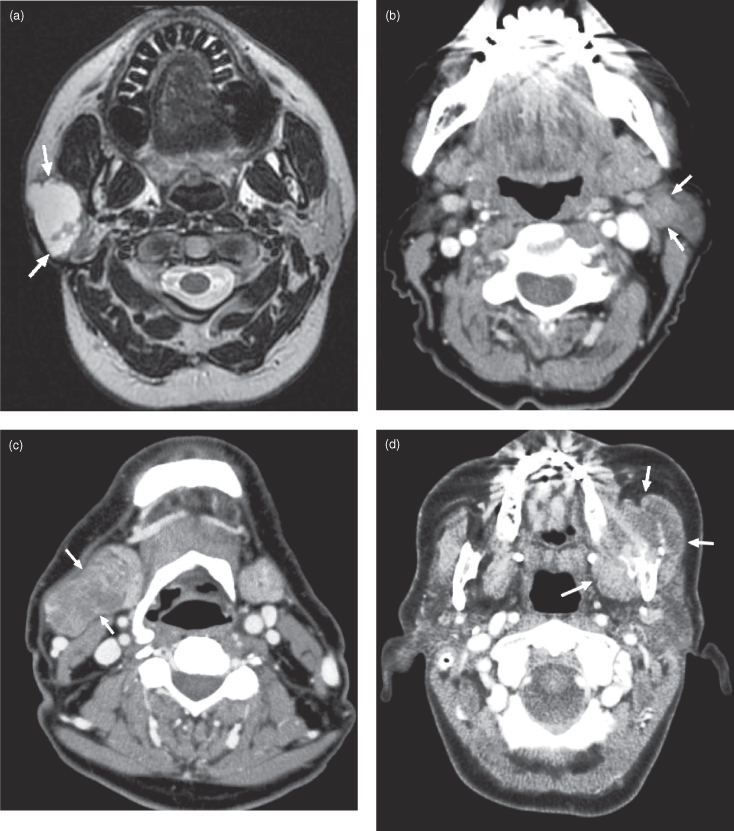

A sampling of rare salivary gland neoplasms are presented in Figure 18.14. The appearance of these lesions correlates with their degree of biological aggressiveness; for example, the mucinous adenocarcinoma in Figure 18.14c is destroying bone, so it is more likely a high-grade lesion. Otherwise the appearance is generally nonspecific with regard to the histological subtype, and diagnosis is made by biopsy or excision rather than by imaging. Figures 18.14a–d are epithelial neoplasms. Figure 18.14e is a nonepithelial tumor: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Figure 18.14. Rare malignant salivary gland neoplasms. (a) Axial T2-weighted MRI of a carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of the right parotid gland (b) Axial postcontrast CT of a myoepithelial carcinoma of the left parotid gland. (c) Axial postcontrast CT of a carcinosarcoma of the right submandibular gland. d) Axial postcontrast CT of a mucinous adenocarcinoma destroying the left mandible. Not only has it substantially destroyed the vertical ramus, but it has displaced the remnant buccally as defined by a broken line of dots just under the masseter muscle. Note the metallic spray artifact anteriorly. (e) Axial postcontrast CT of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma involving both parotid glands.

Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Aerodigestive Tract

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arises from the epithelial layer of the nasopharynx, oral cavity, and larynx and is the most frequent primary malignancy observed in dental practice. In Canada, an estimated 3400 new cases of oral cancer occurred in 2008 with a 2 : 1 male to female ratio. In 2005, the age-standardized incidence rates for nasopharyngeal, lip, floor of mouth, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal sites were 0.61, 0.76, 0.56, 0.32, 0.55 and 2.85 cases per 100,000, respectively. Up to 95% of these cancers are SCCs.35 The median age at diagnosis is 60 years with a 5-year combined survival of approximately 60%.36 The most important associated risk factors for oral cancer are tobacco and alcohol. Smokers have a 5–25 times higher risk of oral cancer,37 and 75% of all oral cancers are attributable to smoking. Heavy alcohol consumption (>30 drinks/week) increases the risk by 9 times35; combining alcohol and smoking increases the risk by 15 times or more.38 The presence of dentures is not a risk factor in itself though sores caused by ill-fitting dentures have been associated with increased SCC incidence.39,40 Viral-induced carcinogenesis plays a role; human papilloma virus infection is strongly associated with oropharyngeal SCC.36,41 Epstein-Barr virus has also been associated with aerodigestive SCCs, particularly in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC: SCC of the nasopharynx), though it is so ubiquitous that it has been hard to prove a causal role.42–44 For NPC there is a significantly higher incidence in East Asians. It is thought to be related to eating salted fish with high levels of nitrosamines.45 The worldwide age distribution for NPC is bimodal with peaks between 15–24 and 65–79 years.46

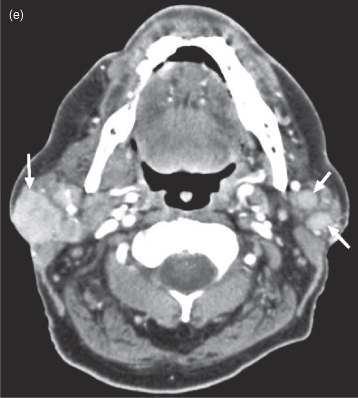

In the aerodigestive tract SCC will typically present a surface abnormality (e.g., erythroplakia, leukoplakia) or a palpable mass. SCC tends to occur in characteristic locations; in the nasopharynx the fossa of Rosenmuller (FOR) is a common site (Figures 18.15–18.17). Posterior NPCs initially produce mild nonspecific symptoms—i.e., Eustachian tube obstruction leading to chronic otitis media, referred pain to the ear, or epistaxis. This makes them challenging to discover at an early stage. As the tumor advances it will characteristically begin to invade adjacent cranial foramina, most commonly traveling superiorly through the foramen ovale into Meckel’s cave (the cave of dura mater which contains the trigeminal ganglion) to produce trigeminal nerve symptoms.47 From here the tumor can extend into the cavernous sinus, occasionally affecting the intracavernous portion of the abducens (6th cranial) nerve to produce lateral rectus muscle palsy and hence diplopia.48 Once in the cavernous sinus, tumor can travel anteriorly to reach the superior orbital fissure and immediately below this extend through the foramen rotundum (Figure 18.16d) into the pterygopalatine fossa. The fossa of Rosenmuller tumor can also travel anteriorly to wrap around the lateral pterygoid plate into the infratemporal fossa. From here cancer can extend medially to enter the pterygopalatine fossa (Figure 18.16a), sometimes connecting to its fellow that has traveled to the same location through the cavernous sinus and foramen rotundum. Tumor in the pterygopalatine fossa can pass medially through the sphenopalatine foramen into the nasal cavity (Figure 18.16a). There are other locations where NPC can enter the skull; sometimes tumor will travel superiorly through the carotid canal, petroclival fissure (Figure 18.16a,c), and/or hypoglossal canal. The latter course will cause hypoglossal nerve dysfunction leading to unilateral tongue atrophy (Figure 18.17a,b). Once inside the skull tumor can elevate the dura (Figure 18.16a), occasionally forming a mass large enough to compress the brain (Figure 18./>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses