Chapter 14

Fractures of the face and jaws

Fractures of the facial skeleton occur due to assault,1 traffic accidents,2 and sporting accidents.3 The last has become increasingly important primarily due to the increased popularity of skiing and snowboarding.3 Although snowboarding injury cases are twice as likely to produce facial fractures than those caused by skiing, skiing is more likely to result in more than one facial fracture.3 The traffic accident cases, despite regulations with regard to seat belts, helmets, and child seats, account for 46% of all facial fractures in a recent Brazilian urban report, whereas assault and sports account for 26% and 6%, respectively.2

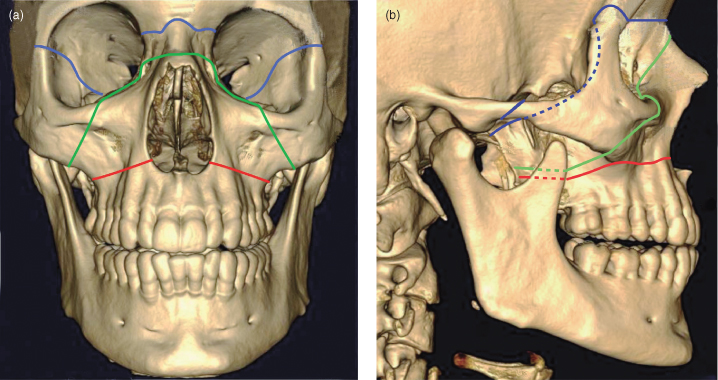

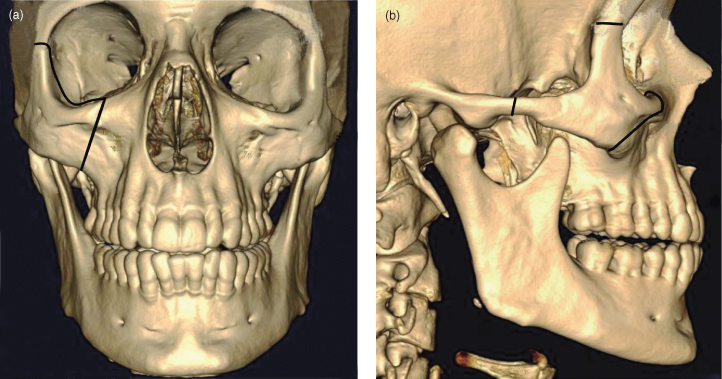

Cross-sectional imaging is frequently required for fractures of the skeleton of the midface. These fractures are generally complex (Figures 14.1–14.3), reflecting the midface’s complex anatomy, which contains the eyes and nose. The classical fracture patterns of fractures of the middle third of the face are the LeFort I, II, and III, (Figure 14.1) and the zygomatic (also called malar) fractures (Figure 14.2).

Figure 14.1. The LeFort fractures of the midface. Red—LeFort I. Blue—LeFort II. Green—LeFort III (fracture through the base of the skull and therefore a neurosurgical referral). Acknowledgment: Bruce McCaughey, Senior Photography/Audio-Visual technician; Faculty of Dentistry; University of British Columbia.

Figure 14.2. Zygomatic fracture, also called malar fracture. Acknowledgment: Bruce McCaughey, Senior Photography/Audio-Visual technician; Faculty of Dentistry; University of British Columbia.

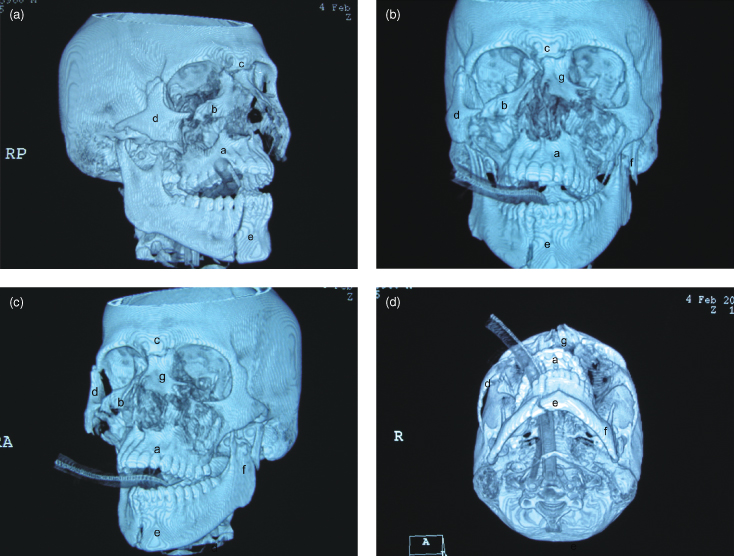

Figure 14.3. A computed tomographic 3D reconstruction of a case features multiple facial fractures. (a) LeFort I; (b) LeFort II; (c) LeFort III; (d) zygomatic fracture; (e) fractured mandible—midline; (f) fractured mandible—condyle; (g) Nasal complex fracture. Note: Left zygomatic bone articulations with adjacent frontal and temporal bones are still intact. Acknowledgment: Dr. Ian Matthew; Faculty of Dentistry; University of British Columbia. Figure 14.3c reprinted with permission from MacDonald-Jankowski DS, Li TK. Computed tomography for oral and maxillofacial Surgeons. Part 1: Spiral computed tomography.

Asian Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 2006;18:68–77.

Of the fractures caused by violence reported by Salonen et al., the most common was the fracture of the nasal bones (35%). LeFort and zygomatic fractures account for 8% and 18%, respectively.1 Twenty-six of their 48 cases of LeFort fractures were asymmetrical. Six of the 22 symmetrical cases each displayed bilateral LeFort I, II, and III fractures. Figure 14.3 displays a 3-D reconstruction of a violent assault case displaying all three LeFort fractures, fractures of the nasoethmoid complex and the mandible.

Fractures of the mandible are usually simple (Figures 1.12, 14.3–14.5) because of the mandible’s shape. The mandible may be described as a bent long bone with a synovial joint at each end. Nevertheless, complex fractures of the mandible can also occur (Figure 14.6.). Furthermore, substantial swelling, which makes the clinical evaluation of the patient difficult, can quickly follow severe facial trauma. Thai et al. reported that the clinical examination was accurate in only two-thirds of mandibular fractures,4 thus emphasizing the importance of radiology to the assessment of the fractured mandible.

Figure 14.4. Panoramic radiograph displaying an undisplaced fracture through the paramedian mandible of this 12-year-old. The two fracture lines indicate fracture of the buccal and lingual cortex ra/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses