Examination, Diagnosis, and Treatment Planning

Diagnosis for Nonorthodontic Problems

Patient Records

The possibilities for a dental examination record for children are endless.

1. Adequately record developmental status and existing pathosis of teeth, supporting structures, head, and neck

2. Record facial and occlusal status

4. Record oral hygiene, periodontal, and intraoral soft tissue status

5. Indicate findings from radiographic and other diagnostic tests

6. Establish a caries risk for the child at that point in time that substantiates preventive and treatment recommendations

1. A caries risk assessment based on the Caries Assessment Tool of the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (see Chapter 13), or some other instrument that accounts for clinical and historical risk factors. This can be a list of factors or simply a choice of high, medium, or low risk.

2. An initial pain or behavior assessment that provides the dentist with a sense of the child’s cooperation or state of oral health upon initial examination. Some clinicians use a set of diagrammatic “faces” ranging from happy to sad (see Figure 6-3). Others use a version of the Frankl behavior scale, which is a four-point selection ranging from definitely positive to definitely negative. The Frankl scale offers the benefits of simplicity and behavior categories that are relevant to chairside dentistry.

The History

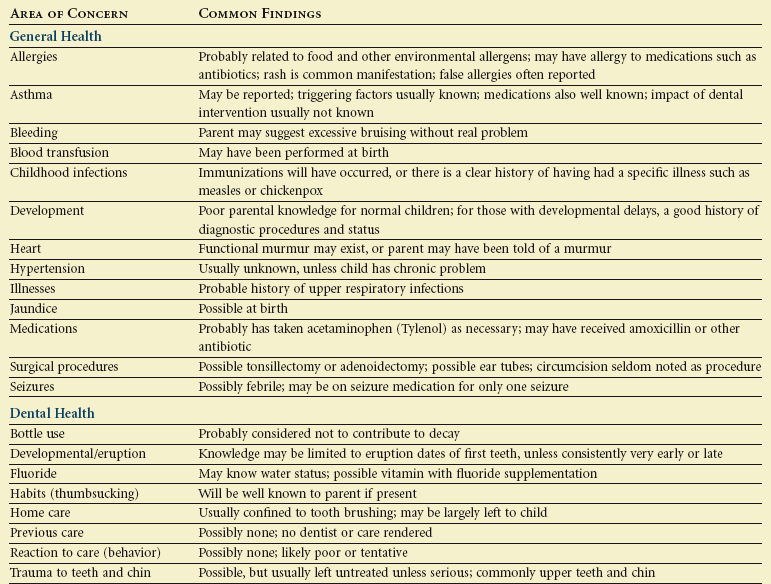

A general health history form can be used to determine a child’s health background if attention is given to specific elements that relate to children. The dentist should be well versed in conditions that relate specifically to children. Table 18-1 provides a list of health items that are particularly common in the 3- to 6-year-old group. The American Dental Association offers a contemporary history form specifically designed for children that covers most childhood health issues.

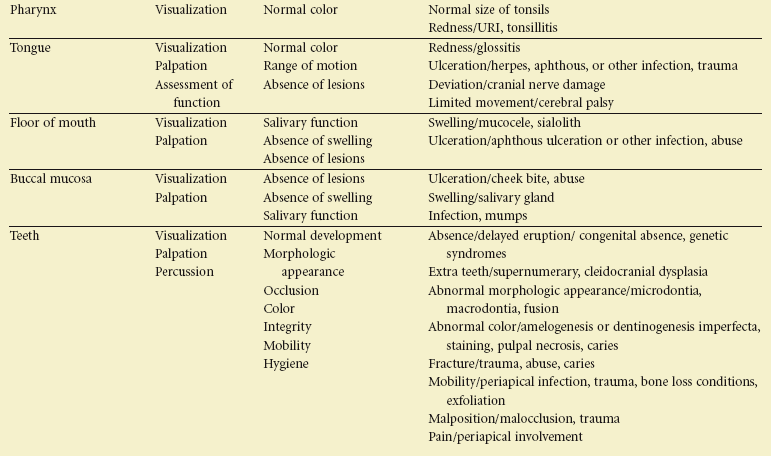

TABLE 18-1

TABLE 18-1

Selected Health History Considerations with Common Findings in the 3- to 6-Year-Old Group

The dental history should be comprehensive. Many parents do not think about recording their child’s dental history other than the eruption of the first tooth. The dental history should cover, at a minimum, past problems and care, fluoride experience, current hygiene habits, and an eruption-developmental profile. Table 18-1 addresses the essential elements of the dental history. The most contemporary approach to the dental history uses a developmental model that permits the parent to address age-specific issues. For example, the health history may ask about bottle use, weaning, access to sweets, and other dietary issues to cover a range of ages on one form. The checklist approach to the health history permits a “not applicable” choice when a child has outgrown a set of questions. This developmental approach provides an age-specific set of findings that can be converted to preventive instruction in the anticipatory guidance counseling by dental staff. Some pediatric dentists tailor the dental history to serve as a screen for caries, orthodontic, gingival, and injury risk factors, asking questions whose answers can later be addressed with take-home preventive advice.

The Examination

Behavioral Assessment

A complete behavioral assessment is discussed in Chapter 23. The general appraisal and chairside examination provide two opportunities to observe behavior and initially assess potential cooperation.

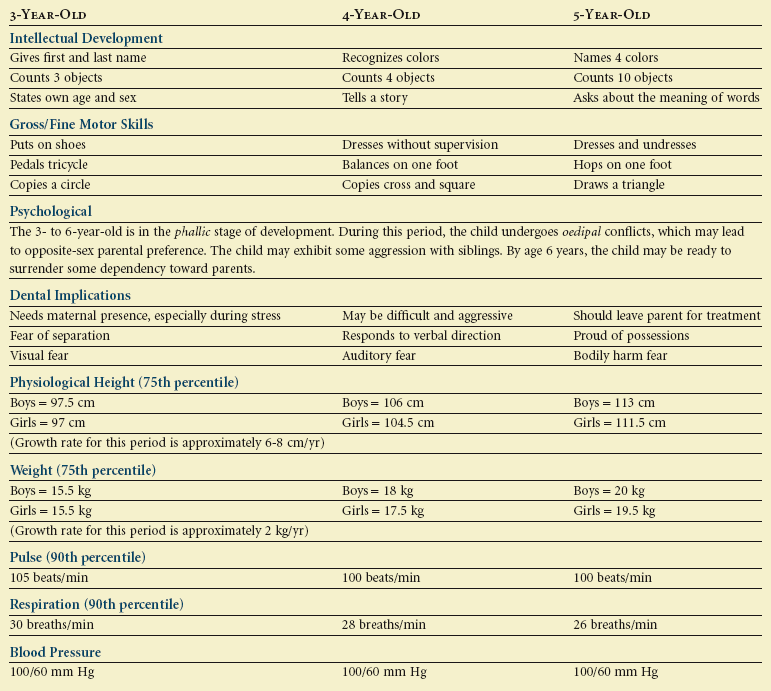

General Appraisal

The general appraisal addresses the child’s physical and behavioral status. The classic areas of this appraisal include gait, stature, and presence of gross signs and symptoms of disease. The normal 3- to 6-year-old is ambulatory, well-coordinated in basic tasks, engaging, and physically healthy in appearance. Table 18-2 lists physical and behavioral milestones for the 3- to 6-year-old child. The dentist should incorporate these markers mentally into a profile for evaluation of the child’s status. The general appraisal of the child is best accomplished in the waiting room or a similar nonthreatening environment. This appraisal should be followed by clarification of any abnormal findings and discussion of potential behavior problems with the parent. The role of vital signs in the general appraisal is twofold. The first purpose is to identify abnormalities, and the second is to satisfy the medicolegal role of providing baseline health data for emergency situations. Vital signs may be distorted if the child is upset or anxious. Taking vital signs of blood pressure, pulse, and respiration may be put off until the child has become accustomed to the environment, but these data must be obtained before any drugs are administered. Weight should be obtained and recorded in a conspicuous location on the chart so that the information is available in an emergency. Height should also be recorded and, together with weight, should serve as an index of physical development. Because of concerns about childhood overweight and obesity, the dentist may choose to calculate a body mass index (BMI) for the child or enter height and weight on standardized growth curves and include these if referring the family to a physician for weight concerns.

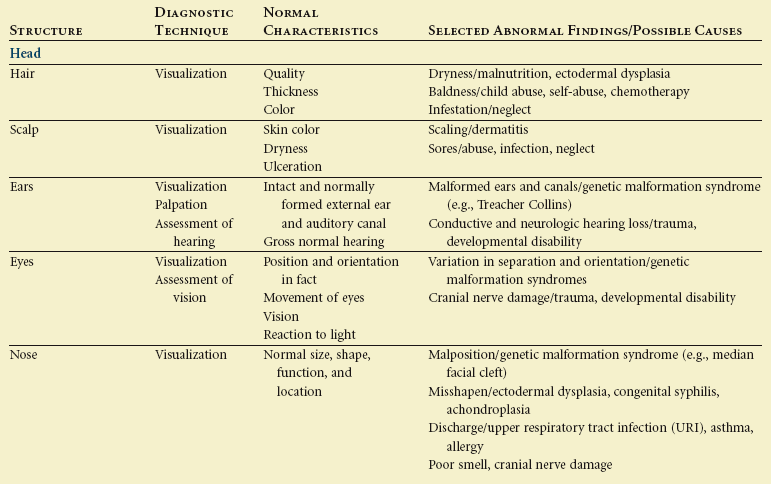

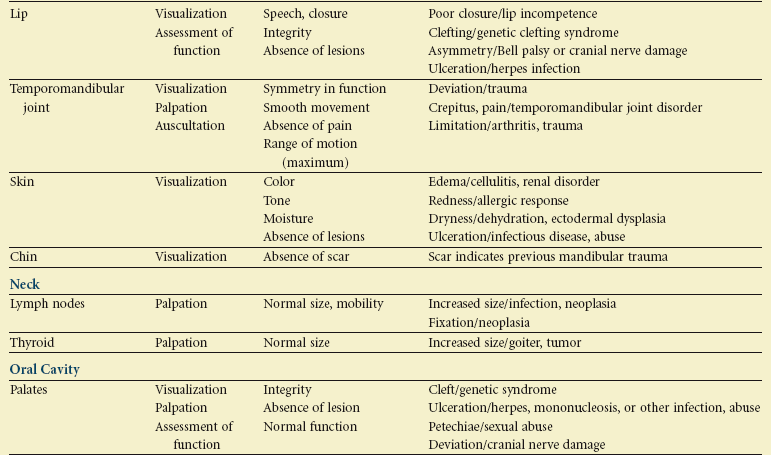

Head and Neck Examination

Table 18-3 outlines the elements and expectations for a thorough head and neck examination. The process begins with an orientation about what is to occur. The dentist should describe what will take place at each step in the examination. This tell-show-do technique, which involves explanation, demonstration, and finally completion of a step, is usually the way the diagnostic process is handled. Positive or negative responses from the child should be encouraged. Children also should be warned and supported before the dentist makes positional changes or begins intraoral manipulation.

Parental presence is always a matter of controversy. Initial parental involvement may be encouraged to allow a transition from a dentist-parent relationship to a more direct dentist-child relationship. This supported transition is important for children younger than 3 years of age but is less threatening for children near school age. Each child reacts differently to having a parent in the operatory, and the dentist must assess the benefit of that presence on the developing relationship he or she has with that child. It is within the parent’s purview to request to be present during the examination and treatment, but it is within the practitioner’s purview to choose not to treat the child under those circumstances. A growing number of practitioners allow parents in the treatment setting, and most data indicate that parents are neutral factors.7

Facial Examination

Overall Facial Pattern

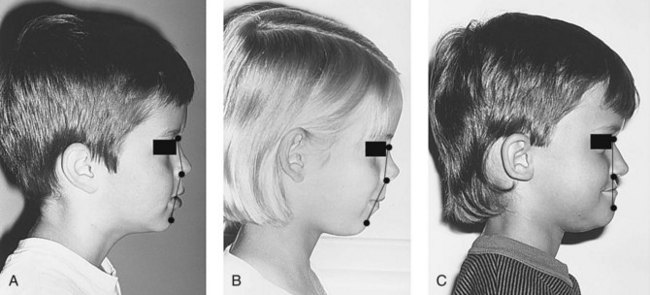

Line segments connecting these points form an angle that describes the profile as convex, straight, or concave (Figure 18-1). A well-balanced profile in this age group is slightly convex. A well-balanced profile in the anteroposterior dimension has an underlying skeletal relationship that is labeled class I (see Figure 18-1, A). This terminology is used because most class I skeletal relationships also have flush terminal plane or mesial step second primary molar relationships and Angle class I or end-to-end permanent first molar dental relationships if those teeth are erupted. Furthermore, the canine relationships usually will be class I, and there will be overjet of 2 to 5 mm. The Angle dental classification is described in a later section.

An assessment of the overall profile gives a general feeling for the skeletal relationships, but this evaluation does not diagnose the reason for the relationships. Some children in this age group have extremely convex profiles (see Figure 18-1, B). This is consistent with a class II skeletal relationship, and these patients usually have distal step second primary molar relationships and class II permanent first molar relationships if those teeth are erupted, class II canine relationships, and increased overjet. Other children have straight or concave profiles (see Figure 18-1, C). These are usually found with mesial step second primary molar relationships and class III permanent first molar relationships, class III canine relationships, and negative overjet.

Positions of the Maxilla and Mandible

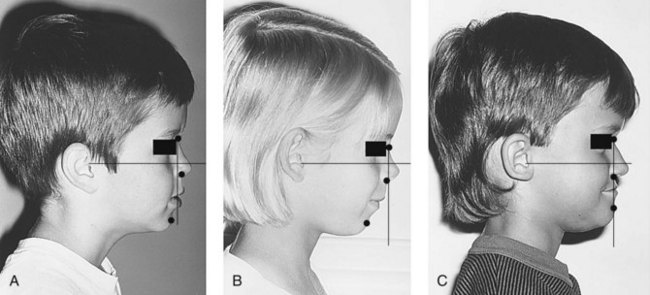

Specifically, in this diagnostic step, the anteroposterior position of the maxilla and mandible are determined. A vertical reference line is extended from the bridge of the nose (the anterior aspect of the cranial base), and the position of other soft tissue points is noted relative to the reference line (Figure 18-2). If the maxilla is properly oriented relative to other skeletal structures, the base of the upper lip will be on or near the vertical line. The soft tissue chin will be slightly behind the reference line if the mandible is of proper size and in the correct position. If the maxilla is positioned significantly in front of the vertical reference line, the patient is said to exhibit maxillary protrusion. If the maxilla is substantially behind the line, the patient exhibits maxillary retrusion. The position of the mandible is described in the same way.

Some caution must be exercised because soft tissue profile relationships do not always accurately reflect the underlying skeletal relationships. Research has shown that the 3- to 6-year-old age group is especially difficult to classify accurately from a profile analysis.4 In addition, vertical facial relationships influence the anteroposterior relationships. This interaction between the horizontal and vertical planes of space and its effect on the profile is discussed later.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline TABLE 18-2

TABLE 18-2

TABLE 18-3

TABLE 18-3

FIGURE 18-1

FIGURE 18-1

FIGURE 18-2

FIGURE 18-2