18

Complementary and alternative medicine

- The major complementary/alternative therapies used in dental practice

- Efficacy, efficiency and evidence

- Integrating ‘alternative’ treatments into dentistry

- Biological dentistry for the 21st century?

Introduction

The General Dental Council (GDC) guidelines indicate that student dental hygienists and therapists should be aware of the many complementary and alternative therapies available for patients. In addition, they should be sensitive to the patient’s right to choose such methods of treatment (General Dental Council, Learning outcomes: www.gdc-uk.org). Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) usually involves those types of treatment that are not part of orthodox medical services. It is a definition that sets these treatments apart from the dominant system of healthcare.

- Complementary therapy: works alongside orthodox healthcare in an attempt to achieve benefits that conventional medicine cannot deliver alone.

- Alternative medicine: usually implies a therapy used instead of more conventional types of treatment.

- Integrative medicine: attempts to combine orthodox approaches with complementary treatments so that a new form of medicine is developed combining both forms of medicine.

More and more patients are seeking and using complementary and alternative remedies, and looking to healthcare professionals to understand these treatments for medical and dental problems.

Over the past 20 years there has been a shift away from labelling complementary therapies as fringe or alternative, to regarding them as integrated medicine. It is also a reflection of the impact of eastern philosophies upon the west. Also, over the last two decades a strong movement towards the idea of taking responsibility for our own health has resulted in a huge demand for methods of healing which take a look at the whole person – emotionally and mentally, as well as physically. There has been a subsequent growth in the popularity of complementary medicines, which has resulted in a much wider availability of remedies in healthfood shops, pharmacies and supermarkets.

Much of complementary medicine is based on the quantum perspective that everything, including our bodies, is energy and the effects of energy meridians on the mental, emotional and physical elements have to be considered. Health is more than an absence of disease; it is a state of balance of the spiritual, emotional, mental and physical aspects of the body. Good oral hygiene and a healthy diet protect teeth and gingivae, as well as helping to prevent systemic disease (Krall, 2001). The basis of holistic care relies on encouraging the body’s own health balance and reducing noxious stimuli.

The holistic (from the Greek holos, meaning whole or complete) dental practitioner, while recording the dental health of each patient, will also look at nutrition, muscle tone and joint function, and assess stress and the effect of toxic materials on the immune system. Above all, by listening to the patient, thinking laterally and looking to other complementary practitioners for support, the patient’s health will be seen as a whole, not as just a set of teeth – a truly holistic approach.

One of the major problems of evaluating the evidence base for alternative therapies is that non-pharmacological treatments such as acupuncture, physiotherapy, chiropractic, etc. are not best evaluated by randomised double-blind controlled trials (RCTs) because the treatment integrates both specific elements (such as needling in acupuncture) with incidental effects such as talking and listening, normally categorised as part of the placebo effect in RCTs. Therefore the use of RCTs for complex interventions may lead to false-negative results (Paterson and Dieppe, 2005).

The patient’s right to choice

Since the Medical Act of 1512 and the Herbalists’ Charter of 1543, orthodox and complementary medicines have worked side by side. Even today the public have a choice between a medical doctor and a lay practitioner. This choice has allowed patients to seek alternative methods of treatment in spite of the fact that many of the therapies are not as yet integrated into the National Health Service (NHS).

It is not within the scope of this book to cover all the many kinds of complementary therapies available but some of the more widely used are described below.

Acupuncture

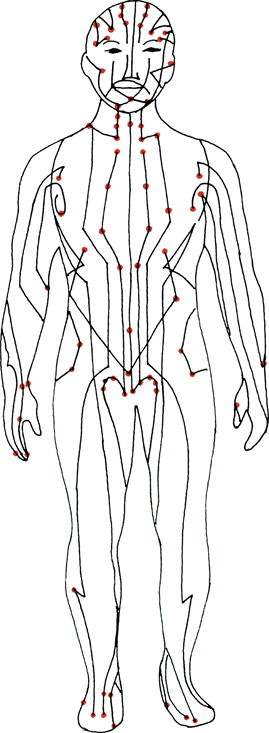

Acupuncture is one of the paramount ‘alternative’ treatments used for pain relief. It is one facet of traditional Chinese medicine and is based on an acupuncture meridian system. This is a network of energetic pathways that run through the body (Figure 18.1) carrying invisible energy (ch’i) which nourishes and vitalises the organs and body tissues. The theory is that any impediment in this circulation leads to an imbalance in the proportions of the Yin and Yang, and thus ill health. Blockages to the flow of the ch’i occur at specific points on the meridians, the acupuncture points. Needling the blockages at these sites would free the flow of the ch’i, allowing this to nourish the organs again, returning normally to the Yin and Yang, and improving health. Function improves, and pain is controlled or cured.

Figure 18.1 Acupuncture meridians of the body.

Dental applications of acupuncture include the control of gagging (Figure 18.2), which is startlingly effective, nausea, treatment of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, stress related headaches linked with TMJ problems (indeed there is increasing evidence for the management of post-operative pain, and even as an adjunct or in some cases alternative to the use of local anesthesia (Figure 18.3). The anesthetic effect is difficult to achieve, however, in the orofacial region.

Figure 18.2 Relieving gagging reflex using electro acupuncture.

Figure 18.3 Acupuncture being used to relieve pain.

Acupuncture also has an excellent reputation for the treatment of such conditions as chronic back and neck pain, tennis elbow, period pain, and chronic headache. Research now tends to show that one of the important aspects to appreciate with acupuncture is that the outcomes are generally no different to conventional therapies, but the approach may be more acceptable, and the side effect profile superior.

How does acupuncture work?

The gate control theory

This theory suggests that when body tissues are damaged there are two separate sets of nerve fibres carrying pain signals. In the body, most pain signals are carried by one type of nerve fibre – the ‘C fibre’. These signals can be interrupted in the central nervous system during transmission to other nerves. This occurs when other signals from a different type of sensory nerve fibre effectively ‘get in the way’ of C fibre transmission – or close the transmission gate. The other nerve fibres may be other pain (A-delta) sensory fibres, or non-painful (‘B’ – touch) sensory fibres. If there are enough alternative sensations travelling, the pain messages will not get through. (This is the principle that TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) operates on, and an approach that has been used in dentistry as a local anaesthesia device, reducing the need for local anaesthetic, adrenaline and analgesics.)

The neuroendocrine theory

This suggests that by utilising acupuncture or acupuncture pressure points Endorphins and serotonin are released. These are part of the body’s own pain control mechanism. There is increasing evidence for this following magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain during acupuncture treatments.

Other forms of acupuncture

Acupressure works on the same principle as acupuncture, but pressure from the hands or fingers replaces needle stimulation.

Electro-acupuncture uses a device to pass a small electrical current across acupuncture points, enhancing the stimulus (Figure 18.2). Laser acupuncture uses low wattage laser light to stimulate the acupuncture sites instead of needles. The basic principles are similar, but the theory and application is complex.

Further information about acupuncture can be obtained from the British Medical Acupuncture Society (www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk).

Herbalism

Herbs are used as a major part of treatment in traditional Chinese medicine and have been used in applications in dentistry, including strengthening the immune system in debilitated patients, and the treatment of periodontal disease both systemically and by the use of herbal mouthwashes. For example, ‘Plaque Off’ tablets containing a dried seeweed (Ascophyllum nodosum) are claimed to reduce the formation of plaque and calculus. Echinacea, prescribed to support the immune system, may have potential in the treatment of periodontal disease. There are reports of ginger and peppermint being effective for nausea, gagging and travel sickness.

There is some concern, however, about the quality and safety of the largely untested ingredients in Chinese medicine. The adverse interactions and dosage of herbs are also a potential problem. For example, St John’s wort, commonly prescribed by herbalists for mild depression, interacts with warfarin and can render the contraceptive pill ineffective. For these reasons, herbs can be harmful and should be prescribed by a dentist only with appropriate training. Further information is available from the North American Institute of Medical Herbalism at http://medherb.com.

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy uses the smells of natural herbs and flowers as therapeutic agents. These agents are reduced to essential oils, usually diluted in a carrier oil and massaged into the skin or inhaled. Lavender, for example, may be useful in the reception or surgery because of its calming properties. Other examples of conditions which have been treated with aromatherapy oils include abscesses (bergamot, lavender), anxiety (camomile, jasmine, lavender), gingivitis (camomile, myrrh) and halitosis (lavender, peppermint). However, essential oils must be treated like medicines and since the evidence base for treating dental conditions by aromatherapy is lacking, claims about its efficacy should be interpreted with considerable caution unless supported by validated research studies. Further information can be obtained from AromaWeb (www.aromaweb.com/articles/default.asp).

Chiropractic

This term is from the Greek chiro (hand) and praktikos (to perform). Chiropractic is a primary healthcare profession that specialises in the diagnosis, treatment and overall management of conditions that are due to problems with the joints, ligaments, tendons and nerves of the body, particularly those of the spine. Treatment consists of a wide range of manipulative techniques designed to improve the function of the joints, relieving pain and muscle spasm, for example, carpal tunnel syndrome (a pinched nerve in the wrist causing tingling and numbness in the hand) which has been reported as a problem by some hygienists (Figure 18.4).

Figure 18.4 Chiropractor treating carpal tunnel syndrome.

Other instances where chiropractic treatment can help are neck and lower back problems which are all too common in the dental profession. It must be remembered, however, that chiropractic does not involve the use of any drugs or surgery. Further information can be obtained from the British Chiropractic Association at www.chiropractic-uk.co.uk.

Osteopathy

This term is from the Greek osteon (bone) and pathos (to suffer). Osteopaths primarily work through the neuromusculoskeletal system, mostly on muscles and joints, and pay special attention to how the internal organs affect, and are affected by, that system. Relevant psychological and social factors also form part of the diagnosis. Another important principle of osteopathy is that the body has its own self-healing mechanisms, which can be utilised as part of the treatment. Osteopathy can help relieve chronic or minor problems, such as upper and lower back pain and repetitive strain injury. It can also provide one-off relief from pain and dysfunction or contribute to the management of long-term complaints.

Further information can be obtained from the British School of Osteopathy at www.bso.ac.uk.

Hypnosis

The use of hypnosis in dental settings can be traced back to the mid nineteenth century, a time when medics were discovering the powerful effects that could be achieved through hypnotic suggestion. Mainly used during these early days as a form of analgesia or anesthesia, there was a clear role for hypnosis since chemical anesthetics and analgestics were not yet available. Around the turn of the twentieth century the work of Freud was famously linked to the psychological use of hypnosis in his study of the unconscious. The scientific study of hypnosis began in the 1930s and has continued ever since. A particular development in contemporary research has been the use of neuroimaging techniques that enable scientists to examine brain functions during hypnosis and this has led to a new wave of interest in the subject. Whilst there is still need for more studies to be carried out in the use of clinical hypnosis there are increasing numbers of well-designed studies, relevant to dentistry (but not necessarily carried out in dental settings) that have gained empirical support. For example studies have demonstrated the efficacy of hypnotic techniques in treating pain, anxiety and phobias as well as in influencing physiology to the benefit of the patient.

One major area of concern for dental professionals is the significant number of people who fail to seek treatment for a considerable period of time due to severe dental anxiety or phobia. An advantage of being ab/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses