6

Oral health education and promotion

- The meaning of health

- Defining health education and health promotion

- Models of health promotion

- Considerations while planning health education and health promotion strategies

- Planning a teaching session

- Evaluating health promotion and education

- Oral health promotion and education samples

- Conclusion

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to define the meaning of health education (HE) and health promotion (HP). The two terms are sometimes interchangeable. Both health professionals and lay people promote and control health. For example, a dental hygienist/therapist may educate a patient on oral hygiene as they have been taught as an undergraduate, the link between dental plaque/bacteria and periodontal disease and dental caries. A lay parent, despite no dental training, may still promote twice daily toothbrushing to her/his child. On a wider scale HP is linked to government initiatives. HP can be delivered in various forms, such as via the media, health professionals or by national campaigning of certain groups and topics. Therefore, everyone is involved in HP and HE.

On a global level, oral disease has a high prevalence in populations that are disadvantaged, either by income and/or socially. Historically, HP and HE focused on individual behaviour that may contribute to ill-health. However, it has been recognised that achieving good oral health goes beyond risk-taking behaviour. Therefore, effective public health strategies and the collaboration of different organisations and health educators contribute to the reduction of poor oral health.

Many white papers have been released from the government to improve health. Choosing Health; Making Healthier Choices Easier (DoH, 2004) identified the need for patients to make informed choices. It outlined that choice may be influenced by a person’s own health needs and expectations. Therefore, the health professional’s role is to assist patients in making healthy choices, which may be facilitated by collaboration between different partnerships. A year later, there was a focus on oral health – Choosing Better Oral Health; An Oral Health Plan for England (DoH, 2005) identified contributions to poor oral health. It recognised that in order to improve oral health, education and different initiatives are essential in order to influence long-term behaviour and develop skills.

However, oral health advice may conflict with other health professionals’ advice. An example may involve the intake of medication with a high sugar content on a regular basis. From an oral health promoter’s point of view, this regular intake may increase the risk of dental caries. It is important that when promoting oral health, that evidence-based information is given. One such guidelines is the Delivering Better Oral Health Evidence-Based Toolkit for Prevention (DoH/BASCD, 2009). Hence, the same messages are being given to patients from all health professionals.

A Dental Care Professional (DCP) will be involved in both HP and HE. Therefore, in order to teach and promote health to others, it is essential that the theoretical aspect of HP and HE are understood. Thus, this chapter will discuss various HP models, as well as the psychology of the interaction, such as communication styles, between the health educator and patient/client.

Meaning of health

It is important for health educators and promoters to be able to define what health means to them and to their patients/clients. Of course, the word ‘health’ has various meanings to different people. Some may relate their idea of health to their present day situation, while others may compare their health in relation to past ill-health or to that of an ill relative/spouse. The concept of health is also influenced by cultural, spiritual and ethnic factors. Whatever its meaning, one thing is clear is that health is essential for everyday living.

How would you define ‘health’? A young person may report health as being able to run a certain distance, or having the right body image. In contrast, an elderly person may report being healthy, despite a complex medical history and regular medication.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined health further as; ‘Health is not merely the absence of disease, but a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being’ (WHO, 1946).

This statement identifies that health is not only related to physical well-being, but also other factors. Furthermore, it appears that if certain resources are lacking, then this may affect health. Is it possible to attain ‘complete health’? The WHO definition gives an impression of an Utopian-type view of health, whereby if we cannot have the ‘completeness’ of the factors that contribute to health, then we can never aspire to attain ‘complete health’. Seedhouse (2001) also suggested that people will achieve their own realistic health potential. However, what has been highlighted for many years, is that ill health can be influenced by several factors. In 1974, The Lalonde Report (Lalonde, 1974) identified four areas that could be targeted in order to improve health. These were:

- Genetic/biological factors – may determine predisposition to a certain disease.

- Lifestyle – certain behaviours which may contribute to disease such as smoking.

- Environment – poor housing, overcrowding and pollution.

- Health services – some patients may not have access to dental care.

Thus, education on its own is not enough. The above factors need to be addressed by using different strategies and collaboration with different services.

Defining health education and health promotion

The term ‘health promotion’ and ‘health education’ are sometimes difficult to define separately. However, HP is a broad concept which also covers HE.

Health education

Generally in simple terms, HE is the active process of transferring information from an organisation/person to a client/patient. This can involve the explanation of cause and effect of disease and the influence of behaviour on health. The aim of HE is to encourage good health by using different strategies. It may include written/verbal information, as well as advising, supporting and developing people’s skills. HE can be given one-to one or to a group. Traditionally, HE may have been delivered in ‘health’ settings, although in recent years HE now influence’s social policies, community action and health of employees (Needs and Postans, 2006).

Health promotion

In 1986, a WHO international conference, The Ottawa Charter, put forward a definition of health promotion as: ‘The process of enabling individuals and communities to increase control over the determinants of health and thereby improve their health’.

Hence, HP is a combination of health education and various support services that enable people to improve their health. It also focuses on groups and aims to prevent disease. Therefore, HP attempts to target the health of a population and incorporates a top-down approach, whereby policies and strategies are put forward to improve health. As already discussed, health is a global concern, as identified in Health for All by the Year 2000 (WHO, 1977, 1985), which highlighted the need to reduce disease and to promote health. On a national and local level, health authorities and primary care trusts incorporate global strategies and targets. Furthermore, partnerships between different groups can promote health. Traditionally, oral health professionals have focused on preventing oral disease by giving advice on their lifestyle/behavioural aspects, such as smoking cessation. However, this is a reductionist point of view, as behaviour and lifestyle choices are influenced by social factors. Likewise, social behaviour is further influenced by economic, environmental and cultural factors. Thus, highlighting the negative effects on health as a result of the patient’s behaviour, may have limited results (Watt, 2005).

The Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986) put forward five main areas of health promotion strategies in order to improve health education/promotion and promote health and reduce inequalities:

- Build public policies that support health. For example, the government level may introduce labels on food, so that consumers are given the correct information and make a choice. Local level policies may concentrate on healthy eating within the nurseries and schools.

- Supportive environments. An example is supporting healthy diets at school.

- Strengthen community action. Involves empowerment of local people. Therefore, this may involve group activity. An example may include local mothers working together to manage sports activities for their children.

- Develop personal skills. This incorporates health education and assists people in developing skills that will contribute to good health. An example of this is the demonstration of interdental cleaning and a ‘tell, show, do’ within the dental setting.

- Reorientate health services. There has been a lot of this in recent years. Different services question why there is poor health and develop strategies in order to overcome this.

Later, the further development of services in order to improve both HE and HP delivery were put forward by The Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century (WHO, 1997).

Thus, HP should involve a more collective responsibility in achieving health. Furthermore, in order to empower people to introduce changes to their lifestyle, public policies and community action need to facilitate these changes and ensure that healthy choices.

Promotion of oral health

Oral health can be described as being without disease and a state whereby the individual can carry out the normal physiological aspects such as eating and speaking. Watt (2005) further suggested that good oral health contributes to general health as it also satisfies psychological and social needs such as communication and appearance.

Oral health education (OHE) may relate to the transfer of information and teaching of new skills to an individual or small group, usually patients. (Needs and Postans, 2006) Oral health promotion (OHP) also includes OHE, but it also focuses on a wider scale; it incorporates different groups, plans different strategies and sometimes legislation.

The DCP needs to be aware of current oral health issues. In 2003, The World Oral Health Report was released (WHO, 2003). WHO determined areas that could contribute to improved oral health such as reduced tobacco use, healthy diet, use of fluoride, promotion of oral health in schools and to the elderly. It also suggested development of ‘oral health systems’ and the need for research to improve oral health. However, inequalities still exist with regards OHP programmes. One reason for this is that the groups that would benefit most from oral health promotion are not able to do so as resources may not be available or limited. Furthermore, it has been reported that dental caries and periodontal diseases have been recognised as the most important key areas for improvement in the status of oral health at a global level (Peterson, 2008). It has also been suggested that other negative influences exist, which may affect the person’s ability to achieve improved oral health. These factors include lifestyle choices/issues, habits that have been established from childhood and therefore may be difficult to change and external pressures such as work and time (Needs and Postans, 2006).

Who is involved in oral health education/promotion?

Many people are involved in OHE and OHP. The previous sections have highlighted the need for collaboration between different services and health professionals. So who is involved in OHE and OHP? The first that come to mind are those that work within the dental settings, such as oral health promoters, dentists, DCPs (hygienists, therapists, dental nurses, lab technicians) and receptionists.

Dental companies and dental/health agencies may promote oral health via a variety of ways, such as the delivery of leaflets, posters, use of media and by advertising. Water companies have introduced public water fluoridation. Other health professionals include health visitors, dieticians, pharmacists and nurses. OHE may also be taught in nurseries and schools as part of the teaching curriculum. On a larger scale, WHO, organisations, governments, the NHS, primary care trusts also are involved. They are responsible for social change and public health policies, as well as forming partnerships between different organisations.

Models of health promotion

Many health promotion models have been introduced and the given examples in this chapter are just a few. Models should be seen to allow a framework in order to guide health promotion programmes.

Ewles and Simnett model (2003)

This model involves five different approaches to the delivery of health promotion. It includes;

- The medical approach aims to have freedom from disease. This approach may be incorporated during different levels of prevention. An example may include promoting the ill-effects of smoking to a smoker. The medical approach is evidence-based; therefore it has a more scientific background.

- The behaviour change approach focuses on individual behaviour. This could be included in smoking cessation advice to an established smoker. However, patients may feel that they are to ‘blame’ for their ‘ill-health’.

- The client-centred approach focuses on the patient’s own agenda. It involves empowering the patient; they ‘lead’ their own health promotion/ intervention activity. An example of this approach is a smoking cessation programme devised, only after the patient has identified smoking as a health concern and the strategy that they want to follow in order to improve their health.

- The educational approach imparts knowledge to groups and individuals. It allows the individual to make an informed choice about a particular behaviour or activity.

- The societal change promotes a healthier environment via social change. An example of this approach was the ban on smoking in public places.

The Ewles and Simnett model puts forward a clear framework in how to promote a certain health promotion subject. But not all approaches may be relevant to the DCP. For example the social change may refer more to organisations that can put forward policies and strategies. Nor does it examine why people make certain choices regard their behaviour, or why people want to improve their health.

‘Stages of Change model’ (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1984)

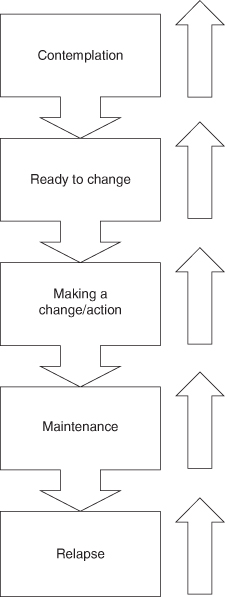

The Stages of Change model (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1984) is based on different types of theories that explain human behaviour. The model has been used to describe addictive behaviour such as smoking, as well as defining clear stages, as outlined in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Prochaska and DiClemente ‘Stages of Change Model’. (Adapted from Prochaska, J. O. and DiClemente, C. C. (1984) Self-change processes, self efficacy and decisional balance across five stages of smoking cessation. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research, 156, 131–140.)

These stages can be described as follows:

- Precontemplation stage. The patient may not be aware that they have a health problem or that it is necessary to change their behaviour. What can the DCP do at this stage? The problems with trying to persuade a smoker to give up smoking is that they may not consider that they are smoking much. Or they may enjoy the social aspect of smoking or may be negative to any smoking cessation advice. Hence, the DCP must first require a willingness of the patient to change their habits before they can accept further help and support. However, education may alert the patient on the health issues associated with smoking.

- The contemplation stage. At this stage, the client may accept that smoking may have a negative effect on their health. They may not have actually sought an action plan yet, such as seeking pharmacological interventions. They are, however, ready to accept advice and guidance. The DCP needs to work through the factors that can contribute to smoking as well as actions to be taken in the smoking cessation programme.

- Ready to change. The patient has weighed up the costs and benefits of smoking. The associated psychological, social and health factors may spur the patient on to make a change to their behaviour. The patient may actively seek advice and guidance from the DCP.

- Making a change/action. The patient may now demonstrate actual commitment to change behaviour, such as seeking out nicotine replacement therapy patches. This action process may be a short or long duration. It is important for the DCP to constantly support and encourage the client in their new regime. This can be achieved by setting goals and review smoking cessation progress. It helps to formulate an agreed plan with the client. Support may also be given by family and friends.

- Maintenance. Not everyone may reach this stage. The same encouragement and support should be given as in the action phase. Sometimes clients may enter this phase briefly before entering the action phase again.

- Relapse. An ex-smoker may move back into the cycle, as the change has not been maintained.

This model has been used many times during health promotion activities, although it does not explain why people may decide to move from one stage to another. It outlines the ‘process’ of behaviour change, yet not everyone moves through these stages in a synchronised fashion, nor does everyone move through all the stages. It also does not take into account social, ethnic and environmental factors that may contribute to a person’s behaviour. However, it does give guidance to health professionals as to the stages of behaviour change and the support that can be given to the patient. The model does not view the relapse as an end point, but just another stage in the continuous cycle.

Health Belief model (Becker, 1974)

This model, explores the psychological aspect of ‘risk’ behaviour. Thus, a person’s behaviour is influenced by factors such as beliefs, culture, class, religion and education. It also depends on the ‘value’ that people may place on their health. Behaviour is also shaped by affective attitudes such as emotions and preferences. Behaviour of course is the outward display of these influences. The Health Belief Model suggests that an individual may adopt a certain behaviour after assessing the pro’s and con’s of a particular action. Therefore a person’s cognitive attitude (knowledge that they possess about a particular health subject) influences their behaviour (Needs and Postans, 2006).

Behaviour is also affected by socialisation, which is a process which enables the individual to participate in group life. By doing so, the individual acquires many human characteristics that may be unique to that group, such as health beliefs. Thus, ‘primary socialisation’ occurs within the family and ‘secondary socialisation’, refers to settings such as within schools or work (Needs and Postans, 2006).

This model explains why people may act in certain ways, but does not give guidance regards planning for a health promotion intervention. The model however, could serve as part of an ethical model and as guidance for oral education delivery.

Determining the type of need

In order to communicate with patients and to ensure that the appropriate health message is being delivered, the DCP needs to determine the level of need that is required by an individual or group. But how can the DCP determine need? This can be obtained from information gained from patients and parents via questionnaires or informal discussions. On a wider scale, demographic health surveys may determine need of a population both globally and nationally. This information can then influence government strategies to improve health.

Different types of need were originally defined by Bradshaw (1972).

- Normative need. This can be determined at global, national and local levels. We as DCPs may also determine this type of need and given our ‘scientific’ background may be influenced by the medical approach. Normative needs also reflect views and values that are held by health professionals. For example a child may have a high incidence of plaque and gingival inflammation. Because of the DCP’s understanding of plaque induced inflammation, the DCP may give intense oral hygiene instruction. The problem with this type of need is that not all professionals may agree on the degree of need. This can lead to loss of confidence from patients.

- Felt need or perceived need. This is actually what the patient feels that they need in relation to their own assessment. This type of need can be identified by questioning the patient. Therefore, the patient with the high level of plaque may not feel that he/she needs oral hygiene instruction. Their own perceived need may be tooth whitening.

- Expressed need. Patients may actually ‘express’ or demand what they require. The expressed need is a request for treatment and therefore requires action. The expressed needs however, need co-operation with normative needs, although ideas may be opposed.

- Comparative need. This type of need is compared between groups or populations. For example, epidemiology studies may identify high decayed, missing and filled teeth (d/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses