Retention

Why Is Retention Necessary?

Although a number of factors can be cited as influencing long-term results,1,2 orthodontic treatment results are potentially unstable and therefore retention is necessary for three major reasons: (1) the gingival and periodontal tissues are affected by orthodontic tooth movement and require time for reorganization when the appliances are removed, (2) the teeth may be in an inherently unstable position after the treatment, so that soft tissue pressures constantly produce a relapse tendency, and (3) changes produced by growth may alter the orthodontic treatment result. If the teeth are not in an inherently unstable position and if there is no further growth, retention still is vitally important until gingival and periodontal reorganization is completed. If the teeth are unstable, as often is the case following significant arch expansion, gradual withdrawal of orthodontic appliances is of no value. The only possibilities are accepting relapse or using permanent retention. Finally, whatever the situation, retention cannot be abandoned until growth is essentially completed.

Reorganization of the Periodontal and Gingival Tissues

Widening of the periodontal ligament space and disruption of the collagen fiber bundles that support each tooth are normal responses to orthodontic treatment (see Chapter 8). In fact, these changes are necessary to allow orthodontic tooth movement to occur. Even if tooth movement stops before the orthodontic appliance is removed, restoration of the normal periodontal architecture will not occur as long as a tooth is strongly splinted to its neighbors, as when it is attached to a rigid orthodontic archwire (so holding the teeth with passive archwires cannot be considered the beginning of retention). Once the teeth can respond individually to the forces of mastication (i.e., once each tooth can be displaced slightly relative to its neighbor as the patient chews), reorganization of the periodontal ligament (PDL) occurs over a 3- to 4-month period, and the slight mobility present at appliance removal disappears.

This PDL reorganization is important for stability because of the periodontal contribution to the equilibrium that normally controls tooth position. To briefly review our current understanding of the pressure equilibrium (see Chapter 5 for a detailed discussion), the teeth normally withstand occlusal forces because of the shock-absorbing properties of the periodontal system. More importantly for orthodontics, small but prolonged imbalances in tongue-lip-cheek pressures or pressures from gingival fibers that otherwise would produce tooth movement are resisted by “active stabilization” due to PDL metabolism. It appears that this stabilization is caused by the same force-generating mechanism that produces eruption. The disruption of the PDL produced by orthodontic tooth movement probably has little effect on stabilization against occlusal forces, but it reduces or eliminates the active stabilization, which means that immediately after orthodontic appliances are removed, teeth will be unstable in the face of occlusal and soft tissue pressures that can be resisted later. This is the reason that every patient needs retainers for at least a few months.

The gingival fiber networks are also disturbed by orthodontic tooth movement and must remodel to accommodate the new tooth positions. Both collagenous and elastic fibers occur in the gingiva, and Reitan showed many years ago that the reorganization of both occurs more slowly than that of the PDL itself.3 Within 4 to 6 months, the collagenous fiber networks within the gingiva have normally completed their reorganization, but the elastic supracrestal fibers remodel extremely slowly and can still exert forces capable of displacing a tooth at 1 year after removal of an orthodontic appliance. In patients with severe rotations, sectioning the supracrestal fibers around teeth that initially were severely rotated, at or just before the time of appliance removal, is a recommended procedure because it reduces relapse tendencies resulting from this fiber elasticity (see Figure 16-18).

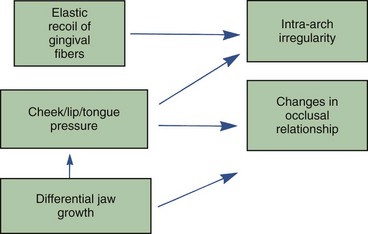

1. The direction of potential relapse can be identified by comparing the position of the teeth at the conclusion of treatment with their original positions. Teeth will tend to move back in the direction from which they came, primarily because of elastic recoil of gingival fibers but also because of unbalanced tongue–lip forces (Figure 17-1).

2. Teeth require essentially full-time retention after comprehensive orthodontic treatment for the first 3 to 4 months after a fixed orthodontic appliance is removed. To promote reorganization of the PDL, however, the teeth should be free to flex individually during mastication, as the alveolar bone bends in response to heavy occlusal loads during mastication (see Chapter 8). This requirement can be met by a removable appliance worn full time except during meals or by a fixed retainer that is not too rigid.

3. Because of the slow response of the gingival fibers, retention should be continued for at least 12 months if the teeth were quite irregular initially but can be reduced to part time after 3 to 4 months. After approximately 12 months, it should be possible to discontinue retention in nongrowing patients. More precisely, the teeth should be stable by that time if they ever will be, and in most patients some degree of re-crowding of lower incisors long term should be expected. Some patients who are not growing will require permanent retention to maintain the teeth in what would otherwise be unstable positions because of lip, cheek, and tongue pressures that are too large for active stabilization to balance out. Patients who will continue to grow, however, usually need retention until growth has reduced to the low levels that characterize adult life.

Occlusal Changes Related to Growth

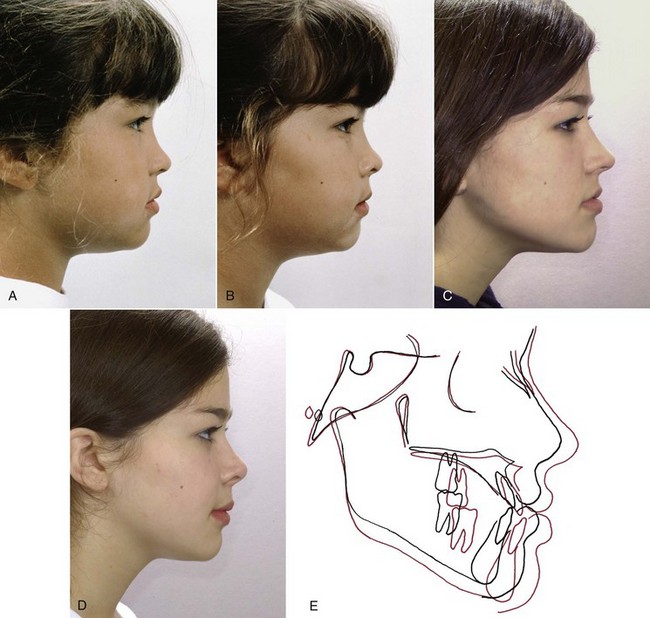

A continuation of growth is particularly troublesome in patients whose initial malocclusion resulted largely or in part from the pattern of skeletal growth. Skeletal problems in all three planes of space tend to recur if growth continues (Figure 17-2) because most patients continue in their original growth pattern as long as they are growing. Transverse growth is completed first, which means that long-term transverse changes are less of a problem clinically than changes from late anteroposterior and vertical growth.

Comprehensive orthodontic treatment is usually carried out in the early permanent dentition, and the duration is typically between 18 and 30 months. This means that active orthodontic treatment is likely to conclude at age 14 to 15, while anteroposterior and particularly vertical growth often do not subside even to the adult level until several years later. Long-term studies of adults have shown that very slow growth typically continues throughout adult life, and the same pattern that led to malocclusion in the first place can contribute to a deterioration in occlusal relationships many years after orthodontic treatment is completed.4 In late adolescence, continued growth in the pattern that caused a Class II, Class III, deep bite, or open bite problem in the first place is a major cause of relapse after orthodontic treatment and requires careful management during retention.5

Retention After Class II Correction

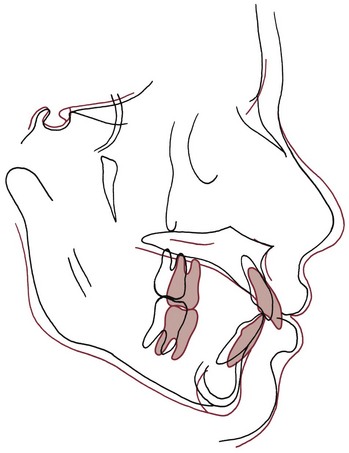

Relapse toward a Class II relationship must result from some combination of tooth movement (forward in the upper arch, backward in the lower arch, or both) and differential growth of the maxilla relative to the mandible (Figure 17-3). As might be expected, tooth movement caused by local periodontal and gingival factors can be an important short-term problem, whereas differential jaw growth is a more important long-term problem because it directly alters jaw position and this contributes to repositioning of teeth.

The other method is to use a functional appliance of the activator-bionator type to hold both tooth position and the occlusal relationship (Figure 17-4). To the patient, this intraoral device is just another variety of retainer, and compliance is less of a problem. If the patient does not have excessive overjet, as should be the case at the end of active treatment, the construction bite for the functional appliance is taken without any mandibular advancement—the idea is to prevent a Class II malocclusion from recurring, not to actively treat one that already exists.

Retention After Deep Bite Correction

Correcting excess overbite is an almost routine part of orthodontic treatment, and therefore the majority of patients require control of the vertical overlap of incisors during retention. This is accomplished most readily by using a removable upper retainer made so that the lower incisors will encounter the baseplate of the retainer if they begin to slip vertically behind the upper incisors (Figure 17-5). The procedure, in other words, is to build a potential biteplate into the retainer, which the lower incisors will contact if the bite begins to deepen. The retainer does not separate the posterior teeth.

Retention After Anterior Open Bite Correction

Relapse into anterior open bite can occur by any combination of depression of the incisors and elongation of the molars. Active habits (of which thumbsucking is the best example) can produce intrusive forces on the incisors, while at the same time leading to an altered posture of the jaw that allows posterior teeth to erupt. If thumbsucking continues after orthodontic treatment, relapse is all but guaranteed. Tongue habits, particularly tongue–thrust swallowing, are often blamed for relapse into open bite, but the evidence to support this contention is not convincing (see discussion in Chapter 5). In patients who do not place some object between the front teeth, return of open bite is almost always the result of elongation of the posterior teeth, particularly the upper molars, without any evidence of intrusion of incisors (Figure 17-6). Controlling eruption of the upper molars therefore is the key to retention in open bite patients.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses