Chapter 17

Benign lesions

The following are some common (and not so common) benign swellings affecting the skull base and suprahyoid region. All of these tumors can be seen on either CT or MRI, although as noted earlier, destructive bony pathology is usually better seen on CT.

Pituitary Adenoma

Pituitary adenomas (Figure 17.1) are benign tumors that arise from the adenohypophysis, or anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. They may be endocrinologically active and secrete the same hormones that the pituitary normally produces, only in excess amount. The most common “functioning” pituitary tumor is a prolactinoma1; the excess prolactin may produce amenorrhea and galactorrhea in women and impotence in men. Both prolactinomas and “nonfunctioning” adenomas occur at approximately the same frequency: 25% of total. Nonfunctioning tumors may present with decreased visual acuity when the tumor begins to compress the adjacent optic chiasm (Figure 17.2). Other lesions that may resemble pituitary adenomas include aneurysms, meningiomas, and schwannomas. Craniopharyngiomas and Rathke’s pouch cysts also occur in the sella but are predominantly cystic instead of solid.

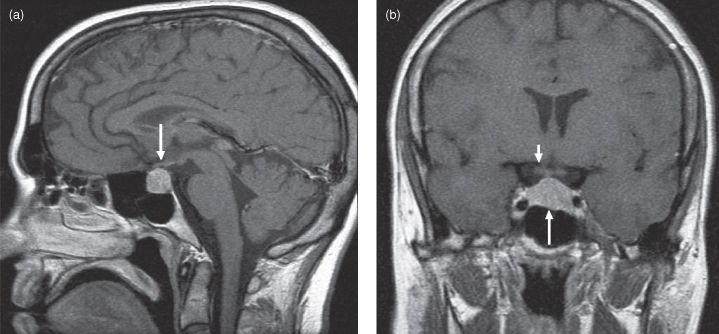

Figure 17.1. Postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI images of a pituitary adenoma. (a) Sagittal plane displays a round, enhancing adenoma of intermediate-high signal intensity (arrow). Note the air-filled sphenoid sinus below it and anterior to the slightly more hyperintense and homogeneous marrow-filled clivus. (b) Coronal plane displays the adenoma (long arrow). Its well-defined lateral margins touch the medial surface of the cavernous sinus bilaterally. The optic chiasma is seen immediately above as an isointense horizontal bar (short arrow pointing to right side of chiasm). The lateral pterygoid muscles are just inserting into the pterygoid pit of the condylar neck.

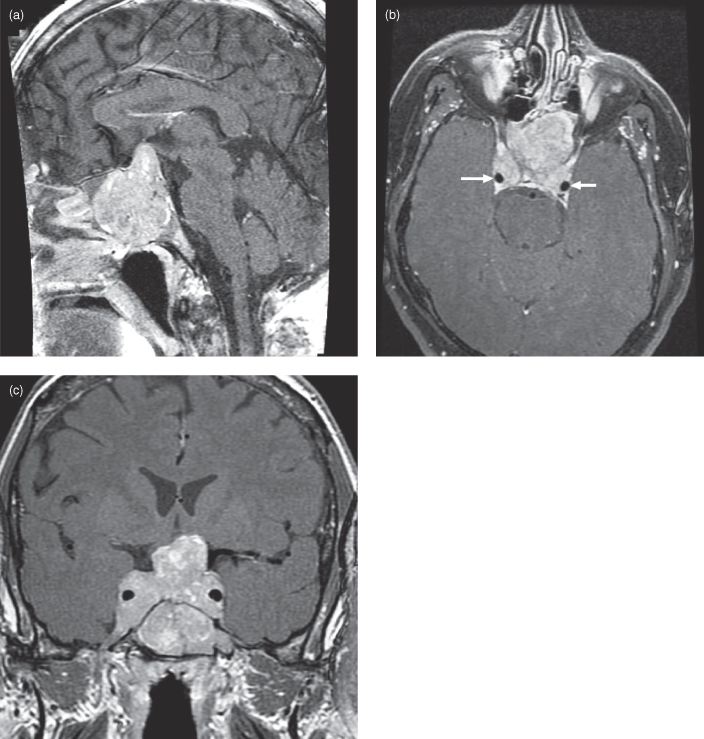

Figure 17.2. Postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI of a considerably larger pituitary adenoma than that displayed in Figure 17.1. It now encases the cavernous portion of the carotid arteries and markedly compresses the optic chiasm, displacing it superiorly. (a) The sagittal plane displays a lobular enhancing adenoma of intermediate–high signal intensity with heterogeneous enhancement. Note that the tumor has traversed the sellar floor to completely fill and expand the adjacent sphenoid sinus. Tumor has also eroded and remodeled the marrow-filled clivus, pushing the superior clival border inferiorly. (b) An axial postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI at the level of the superior surface of the orbit; the superior rectus muscles are displayed. The encased carotid arteries are observed as signal voids (arrows) as is the basilar artery on the anterior aspect of the midbrain. (c) The coronal plane displays the same adenoma. It completely encases the cavernous portion of the carotid arteries. Inferiorly, it fills the sphenoid sinus. The roof of the nasal cavity has been displaced slightly downward. The superior expansion has compressed the optic chiasm and brought the adenoma into broad contact with the hypothalamus. The lateral pterygoid muscles are just inserting into the pterygoid pit of the condylar neck.

Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngiomas are complex cystic, predominantly suprasellar, mass lesions that are frequently partially calcified.2 They are thought to arise from remnants of Rathke’s pouch, an embryologic structure that migrates superiorly from the primitive oral cavity to eventually form the adenohypophysis or anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Craniopharyngiomas comprise 6–13% of all pediatric brain tumors and have a bimodal age distribution, peaking between 5–14 years and after 65 years of age.3,4 Three-quarters of these tumors are suprasellar, with most of the remaining lesions combined sellar-suprasellar. Rarely are they completely intrasellar. The craniopharyngioma usually presents as a small enhancing solid nodule within or adjacent to a lobulated cystic lesion with enhancing walls. The cystic part is often divided into multiple compartments, each with a slightly different though homogeneous T1- and T2-weighted MRI signal intensity. When they become large enough, craniopharyngiomas can produce obstructive hydrocephalus by blocking the foramen of Monroe (Figure 17.3).

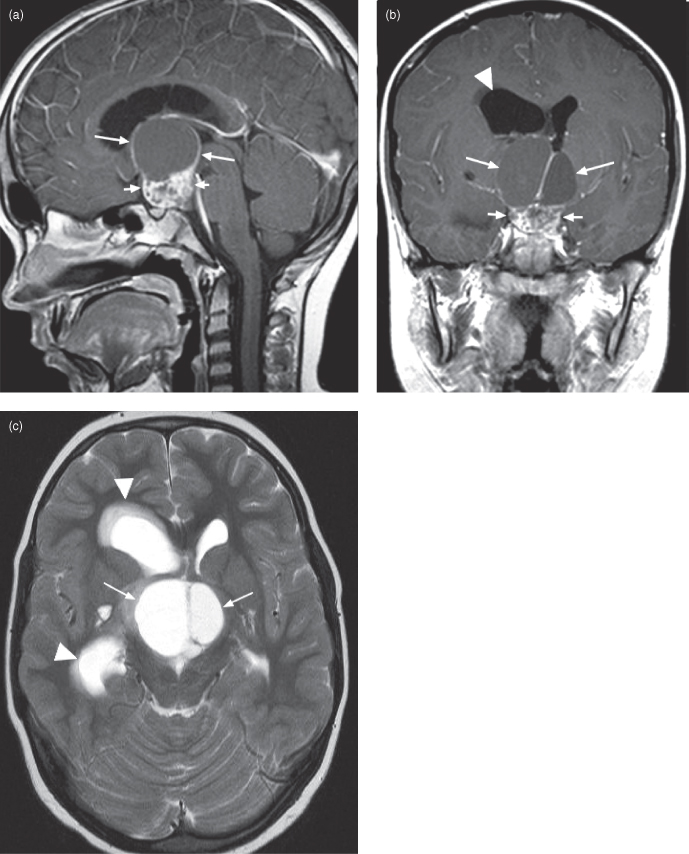

Figure 17.3. Magnetic resonance imaging of a craniopharyngioma producing unilateral intraventricular hydrocephalus. (a) Sagittal postcontrast T1-weighted MRI showing a large complex cystic suprasellar craniopharyngioma. Note the characteristic heterogeneous solid enhancing portion (short arrows) and the large associated cyst with enhancing walls (long arrows). (b) Coronal postcontrast T1-weighted image from the same patient in (a). The solid (short arrows) and cystic (long arrows) parts of the lesion are displayed. The left cyst compartment has a higher signal than its fellow; different cyst MRI signal levels are a common feature of this tumor. The mass is obstructing the right side of the foramen of Monroe, producing unilateral right intraventricular obstructive hydrocephalus. Note the dilated right lateral ventricle (arrowhead). (c) Axial T2-weighted image from the same patient in (a). The cystic portion of the tumor is well seen (arrows). Note the dilated right frontal and temporal ventricular horns; hydrocephalus caused by the tumor.

Rathke’s cleft cysts can sometimes mimic craniopharyngiomas.5 These lesions also arise from Rathke’s pouch and are seen in the same location. Unlike craniopharyngiomas they are generally purely cystic (no solid component), rarely calcify, and minimally enhance with intravenous (IV) contrast.6,7 They also rarely produce symptoms.8

Intracranial Aneurysms

Intracranial aneurysms are focal dilatations of cerebral blood vessel walls with various shapes—some saccular, others fusiform. Arterial aneurysms are commonly caused by injury to the blood vessel walls from atherosclerosis and/or focal hemodynamic pressure. These aneurysms usually occur at vessel bifurcations, most often affecting the middle cerebral, supraclinoid internal carotid, posterior communicating, cavernous carotid, anterior communicating, and vertebrobasilar arteries in descending order of frequency.9 The prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIA) is estimated to range between 0.4–6%, depending on the study design.10 There is a 4% increased risk of having a UIA if a first-degree relative has a cerebral aneurysm.11 Over the course of a lifetime, the risk of an aneurysm rupturing is substantial, estimated from 20% to 50%12; risk increases with the size of the aneurysm. In a 1998 systematic review, Rinkel9 found that in aneurysms under 1 cm the risk is 0.7% per year, and for over 1 cm 4% per year with an overall annual risk of 1.9%.9,10,13 Posterior circulation aneurysms, symptomatic aneurysms, and female gender carry a higher risk of rupture. Incidental aneurysms less than 0.5 mm carry a low risk and conservative management is recommended.14 An increased incidence of cerebral aneurysm is seen in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, fibromuscular dysplasia, Marfan’s and Ehlers-Danos syndromes, and cerebral arteriovenous malformations.15

Since the consequences of intracranial aneurysm rupture can be devastating, imagers must keep a careful eye out for these lesions on routine exams. Larger aneurysms are easily seen on postcontrast CT as well-circumscribed, brightly enhancing structures related to cerebral vessels (Figure 17.4a). Occasionally, an aneurysm wall will calcify, making it easy to see on a noncontrast CT. The appearance of aneurysms on MRI varies depending on the way imaging data was acquired. On T2-weighted images the aneurysm will appear as a dark, hypointense well-circumscribed structure (Figure 17.4b). The inside of the aneurysm is dark rather than bright on T2-weighted images due to the presence of flowing blood. On postcontrast T1-weighted images aneurysms have a heterogeneous internal appearance due to a combination of flow artifact and contrast effect (Figure 17.4d). Smaller aneurysms can be detected with special magnetic resonance techniques (magnetic resonance arteriography) or conventional catheter angiography.

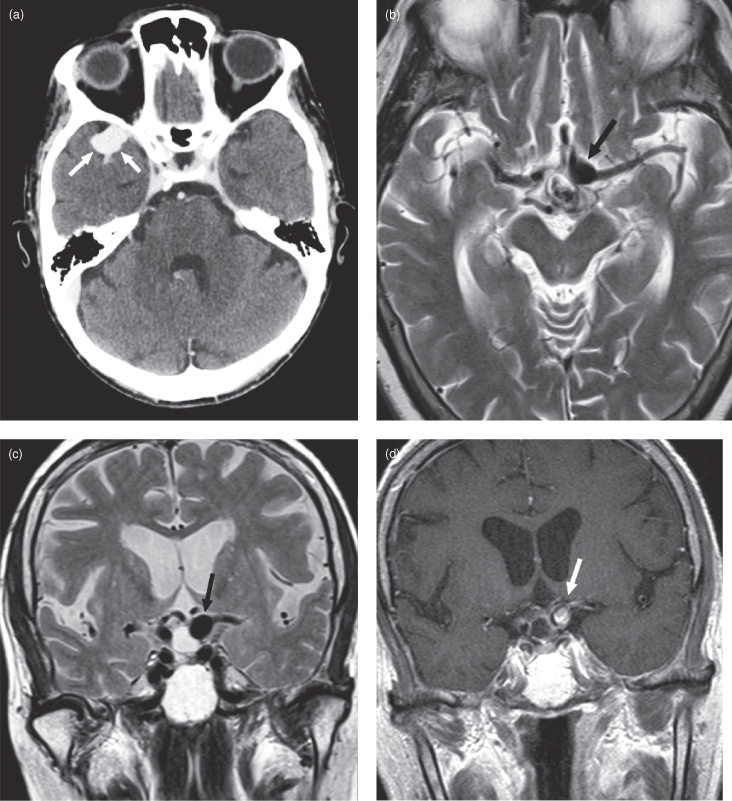

Figure 17.4. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of intracranial aneurysms. (a) Axial postcontrast CT of a distal right middle cerebral artery aneurysm (arrows).Cerebral aneurysms are usually homogeneously bright on postcontrast CT unless they have internal thrombus; then they will have heterogeneous internal density. (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI of a terminal internal carotid artery aneurysm (arrow). Note the low signal within the aneurysm due to the presence of flowing blood. The sharp reader will notice a mixed signal oval structure just posterior and medial to the aneurysm. This is a small craniopharyngioma. (c) Coronal T2-weighted MRI from the same patient in (b). Again the aneurysm is seen as a well-circumscribed hypodense structure. The cystic craniopharyngioma just medial to it is bright. d) Coronal postcontrast T1-weighted MRI from the same patient as (b). Note the mixed signal within the aneurysm due to a combination of flow artifact and intravascular contrast. Most aneurysms are better defined on T2-weighted cuts. Just medial to the aneurysm is a small craniopharyngioma with enhancing walls.

Paragangliomas

These tumors arise from specialized neuroendocrine neural crest cells called paraganglia that are formed in association with autonomic ganglia throughout the body. Since clusters of paraganglia are also called glomus bodies, paragangliomas are also termed glomus tumors. In the head and neck they are found in specific locations with attached names: at the carotid bifurcation (called a carotid body tumor or historically chemodectoma), jugular foramen (glomus jugulare), in the tympanic cavity (glomus tympanicum), and along the extracranial course of the vagus nerve (glomus vagale). Ninety-nine percent of paragangliomas above the shoulders arise in these spots, with just over half at the carotid bifurcation.16 Women predominate, ranging from 67% in a European community17 to 96% in a Latin American study.18 Malignant transformation is rare.19 Most paragangliomas are discovered incidentally during radiological examination for another lesion. These are very vascular tumors and enhance brightly with intravenous contrast (Figures 17.5,17.6).

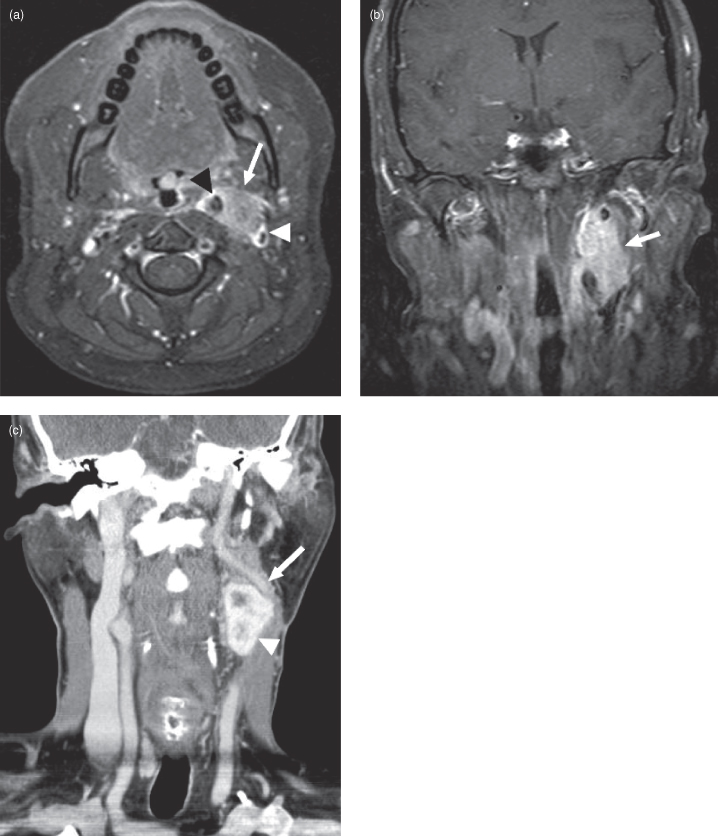

Figure 17.5. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of carotid paragangliomas. (a) Axial postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI of a left carotid paraganglioma (arrow). Note how the internal carotid artery (black arrowhead) and external carotid artery (white arrowhead) are splayed just above the carotid bifurcation. This is a consistent feature of this tumor. (b) Coronal postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI from same patient as (a) showing the longitudinal extent of the mass. (c) Coronal enhanced CT of a different patient. Note how the internal carotid artery has been displaced laterally (arrow). The tumor enhances brightly (arrowhead).

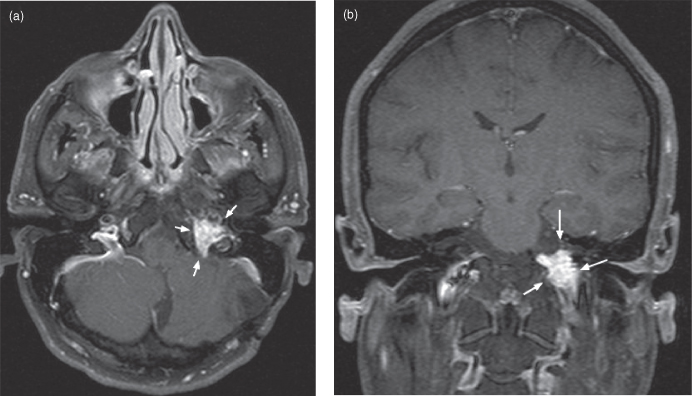

Figure 17.6. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of a jugular paraganglioma (also called glomus jugulare). (a) Axial postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI of a left glomus jugulare tumor (arrows). Note the resemblance to the jugular schwannoma in 17.9. Glomus tumors tend to be slightly more irregular in shape than schwannomas. Unlike schwannomas on T2-weighted imaging they have a “salt and pepper” internal appearance; the dark “pepper” spots are flow voids from numerous internal vessels (not shown). (b) Coronal postgadolinium fat-saturated T1-weighted MRI from same patient as (a) showing a glomus jugulare (arrows).

Schwannomas

Schwannomas are nerve sheath tumors that arise from cells that produce layered myelin covering peripheral nerve axons. They can occur in any peripheral nerve and the majority are benign. In the head and neck, schwannomas are found mostly in cranial nerves but also in nerves arising from cervical roots. They tend to present late because they are slow growing. Most schwannomas occur sporadically, except in neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), a rare autosomal dominant disorder that is characterized by multiple inherited schwannomas, meningiomas, and ependymomas (also called MISME syndrome).20 One of the key diagnostic features of NF2 is the presence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas.

The most common site for schwannomas in the head and neck is the vestibular division of the 8th cranial nerve, hence the vestibular schwannoma. The vestibular schwannoma has also been called acoustic neuroma, which is a misnomer because it occurs very rarely in the acoustic (cochlear) branch of this nerve. Unilateral hearing loss from compression of the adjacent acoustic branch of the 8th nerve is the most common presenting symptom. Small vestibular schwannomas can be completely intracannalicular—i.e., residing within the internal auditory canal (see the right-sided tumor in Figure 17.7). As they get larger they expand the bony canal and travel medially, compressing the brainstem (Figures 17.8, 17.9).

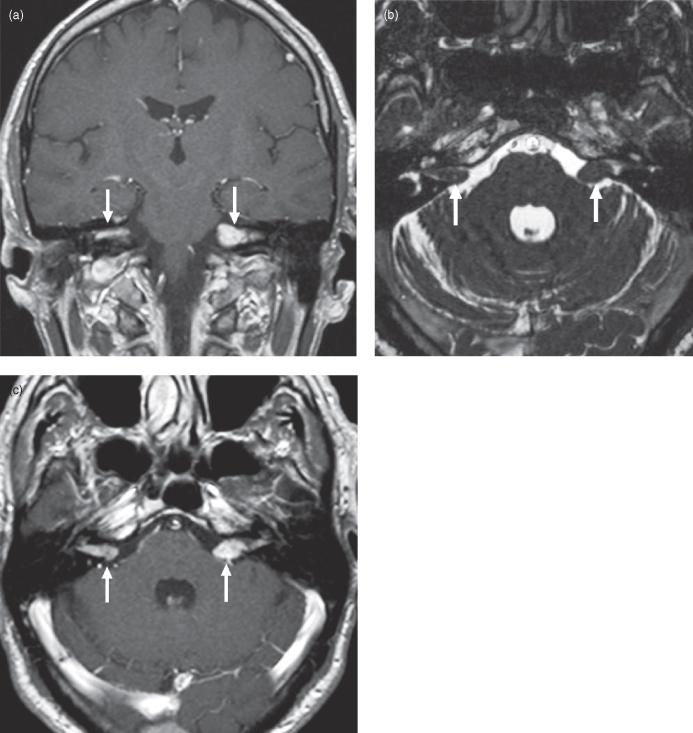

Figure 17.7. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of small bilateral vestibular schwannomas in neurofibromatosis Type 2. (a) Coronal postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI shows enhancement of bilateral vestibular schwannomas (arrows). (b) Axial T2-weighted echo planar MRI shows the left tumor protruding into the perimesencephalic cistern, whereas the right lesion is mostly intracanalicular (arrows). (c) Axial postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI; both schwannomas enhance (arrows).

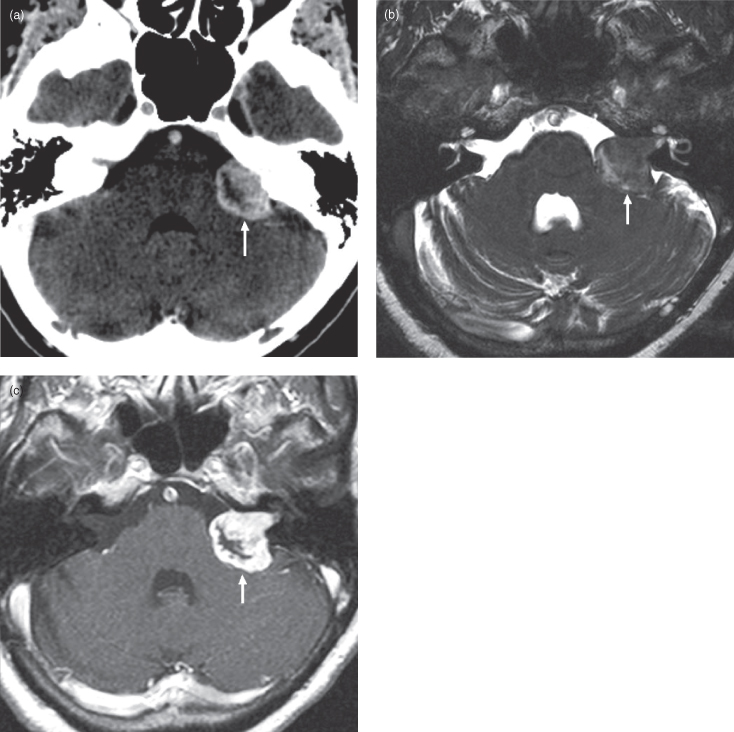

Figure 17.8. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a typical vestibular schwannoma. (a) Axial postcontrast CT showing an enhancing left cerebellopontine angle vestibular schwannoma (soft tissue window). (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI shows the common ice-cream-cone shape; the handle of the “cone” is formed by tumor within the internal auditory canal whereas the “ice-cream ball” is produced by tumor in the perimesencephalic cistern. This lesion is indenting the middle cerebellar peduncle (brachium pontis). (c) Axial postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI shows the usual bright enhancement with oft-seen internal cystic change and/or necrosis.

Figure 17.9. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a variant vestibular schwannoma. (a) Axial T2-weighted MRI d/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses