Acute Gingival Infections

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

Clinical Features

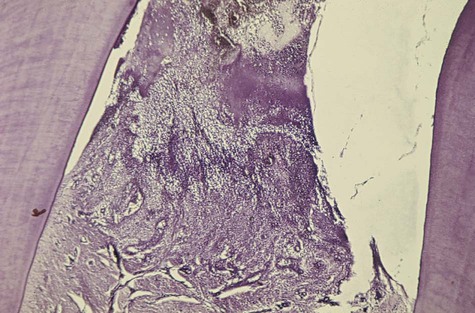

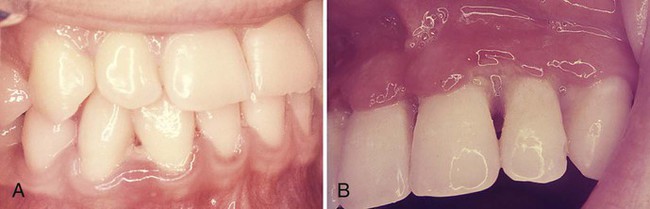

NUG is usually identified as an acute disease. However, the term acute in this case is a clinical descriptor and should not be used as a diagnosis, because there is no chronic form of the disease. Although the acronym ANUG is frequently used, it is a misnomer.57 NUG often undergoes a diminution in severity without treatment, thereby leading to a subacute stage with milder clinical symptoms. Thus, patients may have a history of repeated remissions and exacerbations, and the condition can also recur in previously treated patients. Involvement may be limited to a single tooth or group of teeth, or it may be widespread throughout the mouth (Figure 17-1).

NUG can cause tissue destruction that involves the periodontal attachment apparatus,39 especially in patients with long-standing disease or severe immunosuppression. When bone loss occurs, the condition is called necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP) (see Chapter 24).

Oral Signs.

Characteristic lesions are punched-out, craterlike depressions at the crest of the interdental papillae that subsequently extend to the marginal gingiva and rarely to the attached gingiva and oral mucosa. The surface of the gingival craters is covered by a gray, pseudomembranous slough that is demarcated from the remainder of the gingival mucosa by a pronounced linear erythema (Figure 17-1, A). In some cases, the lesions are denuded of the surface pseudomembrane, thereby exposing the gingival margin, which is red, shiny, and hemorrhagic. The characteristic lesions may progressively destroy the gingiva and the underlying periodontal tissues (see Figure 17-1, B).

Spontaneous gingival hemorrhage or pronounced bleeding after the slightest stimulation are additional characteristic clinical signs (see Figure 17-1, B and C). Other signs that are often found include a fetid odor and increased salivation.

NUG can occur in otherwise disease-free mouths, or it can be superimposed on chronic gingivitis or periodontal pockets. However, NUG or NUP does not usually lead to periodontal pocket formation, because the necrotic changes involve the junctional epithelium; a viable junctional epithelium is needed for pocket deepening (see Chapter 20). It is rare in edentulous mouths, but isolated spherical lesions occasionally occur in the soft palate.56

Relation of Bacteria to the Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis Lesion

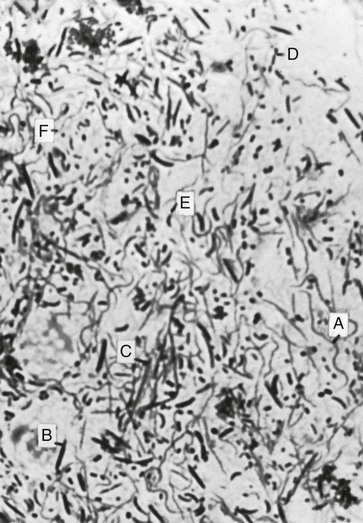

Light and electron microscopy have been used to study the relationship of bacteria to the characteristic lesion of NUG. Light microscopy shows that the exudate on the surface of the necrotic lesion contains microorganisms that morphologically resemble cocci, fusiform bacilli, and spirochetes.71 The layer between the necrotic and living tissue contains enormous numbers of fusiform bacilli and spirochetes in addition to leukocytes and fibrin. Spirochetes and other bacteria invade the underlying living tissue.4,12,16,36

Spirochetes have been found as deep as 300 µm from the surface. The majority of spirochetes in the deeper zones are morphologically different from cultivated strains of Treponema microdentium. They occur in non-necrotic tissue before other types of bacteria, and they may be present in high concentrations intercellularly in the epithelium adjacent to the ulcerated lesion and in the connective tissue.35

Smears from the lesions (Figure 17-3) show scattered bacteria (predominantly spirochetes and fusiform bacilli), desquamated epithelial cells, and occasional PMNs. Spirochetes and fusiform bacteria are usually seen with other oral spirochetes, vibrios, and filaments.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings of gingival pain, ulceration, and bleeding. A bacterial smear is not necessary or definitive, because the bacterial picture is not appreciably different from that of patients with marginal gingivitis, periodontal pockets, pericoronitis, or primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.55 However, bacterial studies are useful for the differential diagnosis of NUG and specific infections of the oral cavity (e.g., diphtheria, thrush, actinomycosis, streptococcal stomatitis).

Differential Diagnosis.

NUG should be differentiated from other conditions that resemble it in some respects, such as herpetic gingivostomatitis (Table 17-1); chronic periodontitis; desquamative gingivitis (Table 17-2); streptococcal gingivostomatitis; aphthous stomatitis; gonococcal gingivostomatitis; diphtheritic and syphilitic lesions (Table 17-3); tuberculous gingival lesions; candidiasis, agranulocytosis, and dermatoses (pemphigus, erythema multiforme, and lichen planus); and stomatitis venenata. Treatment options for these diseases vary dramatically, and improper treatment may exacerbate the condition. In the case of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, early diagnosis may result in treatment with antiviral drugs that would be ineffective for NUG, whereas the treatment of a case of herpes with the debridement required for NUG could exacerbate the herpes. (See Chapter 19 for descriptions of most of these conditions.)

TABLE 17-1

Differentiation Between Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis and Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

| Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis | Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis |

| Etiology: interaction between host and bacteria, most probably fusospirochetes | Specific viral etiology |

| Necrotizing condition | Diffuse erythema and vesicular eruption |

| Punched-out gingival margin; pseudomembrane that peels off and leaves raw areas | Vesicles rupture and leave slightly depressed oval or spherical ulcer |

| Marginal gingiva affected; other oral tissues rarely affected | Diffuse involvement of gingiva; may include buccal mucosa and lips |

| Uncommon in children | Occurs more frequently in children |

| No definite duration | Duration of 7 to 10 days |

| No demonstrated immunity | Acute episode results in some degree of immunity |

| Contagion not demonstrated | Contagion |

TABLE 17-2

Differentiation Among Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis, Chronic Desquamative Gingivitis, and Chronic Periodontal Disease

| Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis | Desquamative Gingivitis | Chronic Destructive Periodontal Disease |

| Bacterial smears show fusospirochetal complex | Bacterial smears reveal numerous epithelial cells and few bacterial forms | Bacterial smears variable |

| Marginal gingiva affected | Diffuse involvement of marginal and attached gingivae and other areas of oral mucosa | Marginal gingiva affected |

| Acute history | Chronic history | Chronic history |

| Painful | May or may not be painful | Painless if uncomplicated |

| Pseudomembrane | Patchy desquamation of gingival epithelium | Generally no desquamation, but purulent material may appear from pockets |

| Papillary and marginal necrotic lesions | Papillae do not undergo necrosis | Papillae do not undergo noticeable necrosis |

| Affects adults of both genders and occasionally affects children | Affects adults, most often women | Generally found in adults, occasionally found in children |

| Characteristic fetid odor | No odor | Some odor present but not strikingly fetid |

TABLE 17-3

Differentiation Among Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis, Diphtheria, and Secondary Stage of Syphilis

| Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis | Diphtheria | Secondary Stage of Syphilis (Mucous Patch) |

| Etiology: interaction between host and bacteria, most probably fusospirochetes | Specific bacterial etiology: Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Specific bacterial etiology: Treponema pallidum |

| Affects marginal gingiva | Rarely affects marginal gingiva | Rarely affects marginal gingiva |

| Membrane removal easy | Membrane removal difficult | Membrane not detachable |

| Painful condition | Less painful | Minimal pain |

| Marginal gingivae affected | Throat, fauces, and tonsils affected | Any part of mouth affected |

| Serologic findings normal | Serologic findings normal | Serologic findings abnormal* |

| Immunity not conferred | Immunity conferred by an attack | Immunity not conferred |

| Doubtful contagiousness | Contagion | Only direct contact will communicate disease |

| Antibiotic therapy relieves symptoms | Antibiotic treatment has minimal effect | Antibiotic therapy has excellent results |

Streptococcal gingivostomatitis is a rare condition that is characterized by a diffuse erythema of the gingiva and other areas of the oral mucosa.42 In some cases, it is confined as a marginal erythema with marginal hemorrhage. Necrosis of the gingival margin is not a feature of this disease, and there is no notable fetid odor. Bacterial smears show a preponderance of streptococcal forms, which were identified as Streptococcus viridans, but other studies report findings of group A β-hemolytic streptococcus.37

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses