Chapter 16

Problem-Solving Challenges in Periapical Surgery

Problem-solving challenges encountered in periapical surgical considerations addressed in this chapter are:

“Probably the first requisite for a successful operation is that the operator should be thoroughly familiar with the anatomy of the region.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

“Pulpless teeth, no matter how well filled, with the slightest previous history of functional or periodontal disturbance which showed any evidence of apical denudation (as indicated by variation in the lamina dura and trabeculae and periodontal width, when compared with adjacent normal teeth) should be root resected.”

Rationale for Surgical Endodontic Treatment

There are multiple treatment planning options for root-treated teeth that develop recurrent periapical pathosis or have periapical lesions that fail to heal following adequate root canal treatment. While nonsurgical revision is usually the clinical treatment of choice,

It may appear that no treatment and a watchful waiting period is an additional option, but in reality, this approach only delays the decision to choose one of the other viable treatment plans. Furthermore, a significant delay in treatment may result in irreversible bone loss and limit the ultimate choice of treatment to extraction.

The theory and treatment planning behind the choice of periapical surgery has not varied much from the earliest citations in the endodontic literature.

Indications for Apical Surgery

Failure of Nonsurgical Root Canal Treatment or Persistent Apical Radiolucencies

Several etiologies have been identified for persistent periapical pathosis following nonsurgical root canal treatment.

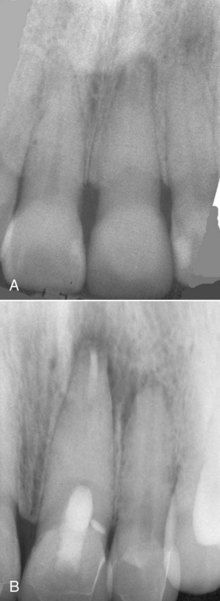

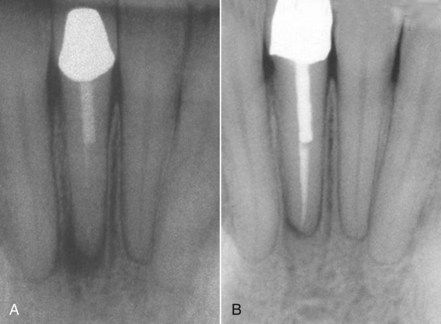

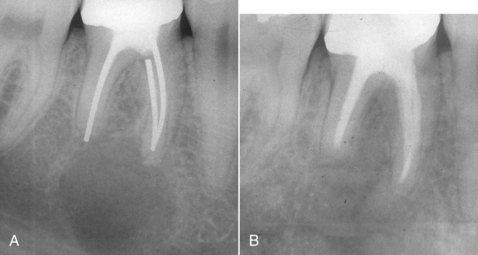

FIGURE 16-1 A, Maxillary lateral incisor with inadequate root canal treatment. Note that the apical canal anatomy has not been altered during the root canal. B, Mandibular molar with inadequate root canal treatment and persistent apical pathosis. There has been no alteration of the apical canal morphology, owing to complete lack of apical preparation.

FIGURE 16-2 A, Persistent periapical pathosis on a tooth with inadequate root canal treatment. B, Following removal of the crown and post, routine root canal procedures were used in revision. Reevaluation at 8 months indicating normal healing.

Inadequate nonsurgical root canal treatment in teeth with significant alteration of the root canal morphology is not unusual in cases with recurrent or persistent apical pathosis (

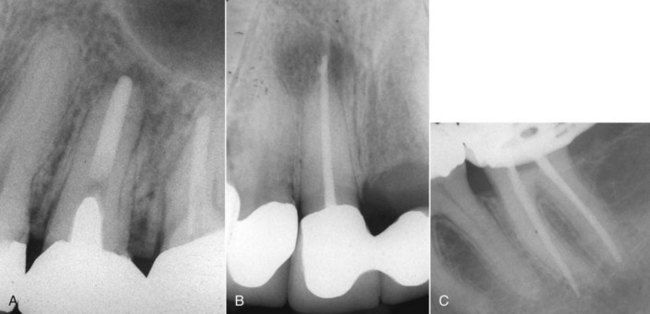

FIGURE 16-3 A, Inadequate root canal treatment with significant alteration of the canal morphology. It appears that the apical foramen was grossly enlarged. B, Inadequate root canal treatment with perforation of the apical foramen. C, Inadequate root canal treatment with alteration of the canal morphology. Periapical surgery would be required to treat all three of these cases.

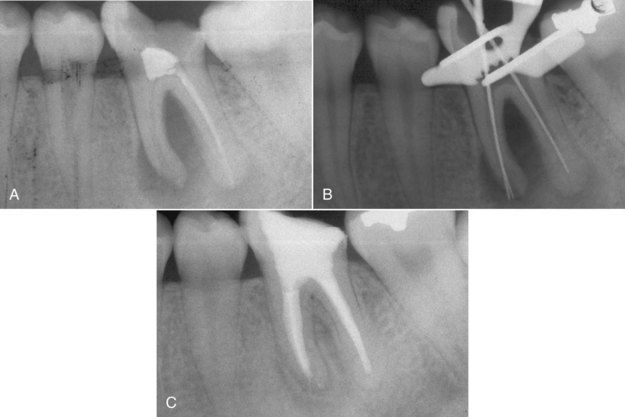

FIGURE 16-4 A, Recurrent periapical pathosis on a mandibular molar with inadequate root canal treatment. B, Working length measurement radiograph indicating significant alteration of the apical canal morphology from the original treatment. C, Reevaluation at 8 months indicating excellent periapical and furcation healing.

Four causes of persistent periapical pathosis that are unlikely to be identified or differentiated by clinical or radiographic means

FIGURE 16-5 Demineralized tooth demonstrating inaccessible canal spaces at the apex along with the presence of silver cone corrosion product that contributed to persistent periapical pathosis.

FIGURE 16-6 A, 6-month reevaluation after root canal treatment of a mandibular left central incisor indicating the lesion had failed to heal. B, Postsurgical treatment radiograph. During surgery, multiple accessory canals were observed as the apical bevel was prepared. The canal had been well filled.

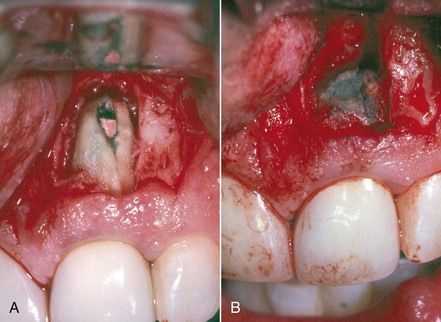

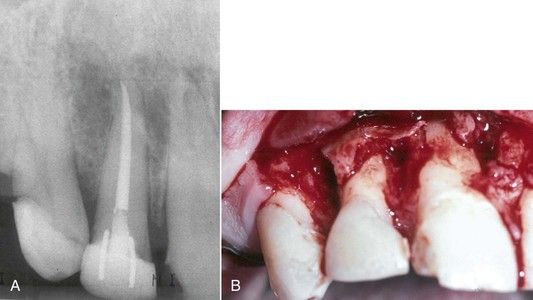

FIGURE 16-7 A, Large radiolucency around maxillary right incisors. Root canal treatment had no impact on the course of the acute infection. Infection gradually involved the bone of adjacent vital teeth. B, Surgical exposure and curettage 1 week after root canal treatment. The infection continued. The central and lateral incisors were ultimately extracted, after which healing progressed uneventfully.

FIGURE 16-8 A, Large radiolucency associated with a failed root canal with silver cones. B, Reevaluation after 6 months indicating radiographic resolution of the lesion. Histologic examination confirmed a true cyst.

Residual bacteria located in inaccessible parts of the root canal system have been the subject of considerable research. Histologic studies of resected root tips and microbiologic studies of bacteria sampled from root canals have identified that the majority of root canal treated teeth with asymptomatic periapical periodontitis harbored persistent bacteria in the apical portion of the complex root canal system.

FIGURE 16-9 A, Histologic section of a resected root apex from the mesial buccal root of a maxillary first molar. Note the canal with the arrow was cleaned, shaped, and obturated, but the canal configurations in the rest of the root were not touched during root canal procedures. Tissue debris is still present, and at the end of the root, there is a cyst forming (EP, epithelium). B, Resected root apex from a maxillary lateral incisor demonstrating multiple canal openings and irregularities. Thorough cleaning and disinfecting of these aberrations is all but impossible and may hold the irritants that result in persistent periapical pathosis.

Cases of persistent periapical infection caused by bacteria that persist after adequate root canal treatment are not common. In some cases, these pathogens have established a recalcitrant extraradicular infection that requires surgery.

The diagnosis of vertical root fractures was discussed in

Reaction to Foreign Bodies in the Periapical Tissues

At times gutta-percha filling material may be inadvertently extruded through the apical foramen or lateral foramina during obturation.

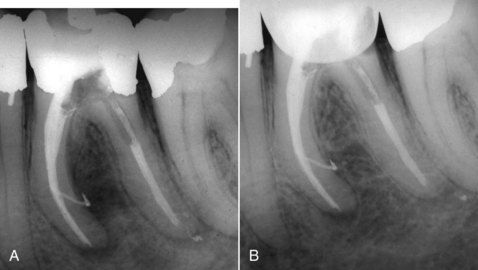

FIGURE 16-11 A, Obturated mandibular molar with extrusion of filling materials out of a large lateral canal in the mesial root and the apical foramen of the distal root. Note the extent bone destruction in the furcation. B, Healing in progress 6 months later.

Occasionally, excessive material may be extruded, which clearly does not look “esthetic” on the postoperative radiograph. Nevertheless, if the apical foramen is clean and well sealed, lesions will heal around the extruded material. Assuming the patient is comfortable, the best postoperative course is reevaluation in 6 to 12 months (

FIGURE 16-12 A, Inadvertent extrusion of gutta percha through the apical foramen during routine obturation. B, Six-month reevaluation indicating normal healing despite the presence of the extruded material.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

Root canal treatment was completed 1 month previously on the maxillary right first molar. The postoperative radiograph indicated an acceptable and unremarkable result. The patient continued to complain that since the day of treatment, there has been a small lump over the apex in the vestibule that remains tender to touch. Clinical examination confirms the small nodule that is locally inflamed and sore to palpation.

Solution

The apices of many maxillary premolar and molar buccal roots are very superficial relative to the surface of the bone (fenestration) (

Paste-type root filling materials are largely uncontrollable when placed with a lentulo spiral. If the apical foramen is naturally large or has been enlarged during canal cleaning and shaping, the paste material can be forced through the apex into apical bone, the sinus, or the mandibular canal. Excessive extrusion of these materials can result in persistent periapical pathosis. Surgery is indicated to both remove the excess and ensure the canal is filled properly at its terminus (

FIGURE 16-15 A, Radiograph illustrating extrusion of paste filling material into the maxillary sinus. B, Radiograph demonstrating gross extrusion of paste filling material into the periapical bone of the maxillary right lateral incisor, causing acute periapical periodontitis. C, Clinical photograph depicting removal of the extruded material during periapical surgery.

Root Canal Anatomy That Is Impossible to Manage Nonsurgically

Some teeth have root shapes that prove impossible to treat nonsurgically. Severe curvature combined with calcifications can prevent negotiation to the terminus of the root canal (

FIGURE 16-16 Radiograph of a mandibular premolar with severe apical curvature in the canal that proved to be nonnegotiable to the apex. Surgery was indicated to resolve the persistent apical periodontitis.

Anatomic Obstructions

The standard of care for treatment of teeth with open apices centers around techniques and materials that result in the formation of a calcified apical barrier. Apical surgery would be indicated in cases that fail to develop the barrier or in which the canal anatomy prevents using the technique.

FIGURE 16-17 A, Dens in dente formation in developing lateral incisor. B, Five–year reevaluation indicating an apical lesion and incomplete apex formation. The patient presented on emergency with an acute apical abscess. C, A 19-month postsurgical reevaluation indicating excellent healing.

Five years later, the patient developed an acute apical abscess, and the periapical film at the time of emergency treatment confirmed that the apex had not developed. It was judged that nonsurgical access through the dens in dente would be destructive and would in itself diminish the long-term prognosis of the tooth. Apical surgery in this case was the most effective and least invasive option.

One of the most common complications in routine root canal treatment is the presence of calcified material in the root canal space.

FIGURE 16-18 Calcification made negotiation to the apex impossible in any canal in this maxillary first molar. Surgery is indicated if symptoms persist or an apical lesion develops in the future.

FIGURE 16-19 Mandibular molar with persistent periapical pathosis. The attempt to negotiate the mesial canals was unsuccessful. Periapical surgery was indicated.

It is almost always appropriate to make a traditional access to the canal space and attempt to locate the canal. Ultimately, if the canal cannot be negotiated, the attempt should be terminated before excessive destruction of coronal tooth structure or a perforation occurs. Subsequently the tooth should be restored and periapical surgery treatment planned (

Iatrogenic Obstructions

The term iatrogenic refers to adverse complications caused by previous treatment. In the case of obstructions, it would be the presence of irretrievable dental materials or instruments in the canal space that prevent the use of nonsurgical revision techniques (see

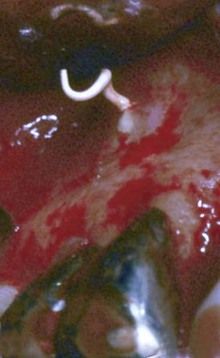

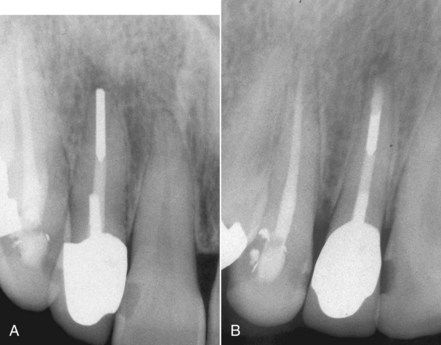

One technique which is particularly difficult to revise nonsurgically is the sectional silver cone that was placed to allow space for an intraradicular post. Fortunately, the use of silver cones is obsolete, but a legacy of cases remain. In the event the silver cone section is not removable nonsurgically, apical surgery is indicated. Fortunately in many cases, it is possible to remove the entire piece of silver cone from the apical direction because many will be found to be loose in the canal following resection. If the silver cone can be removed, apical preparation can proceed in the usual manner without complication.

If the silver cone cannot be removed, the apical preparation (described later in this chapter) becomes much more complicated. The metal will have to be cut back with a very small bur or diamond-coated ultrasonic tip to create a cavity preparation for the root-end filling material (

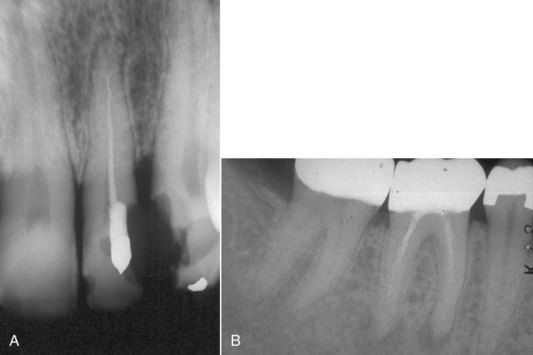

FIGURE 16-21 A, Root canal completed with a sectional silver cone. A symptomatic lesion is present. B, After an unsuccessful attempt at removal, surgery was completed.

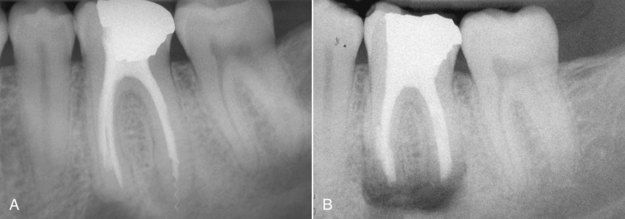

When separated instrument fragments cannot be removed, surgery is indicated to clean and fill the apical portion of the root canal. If the instrument fragment does not extend to the apex, it is not necessary to remove it. In fact, the attempt to remove it may excessively destroy root structure. Instrument fragments at the apex or protruding through the apex can frequently be removed during surgery, which greatly facilitates apical preparation and placement of a root-end filling (

FIGURE 16-22 A, Root-treated mandibular first molar with periapical pathosis. Note the separated instrument extending through the apex of the distal root. B, Immediate postsurgical radiograph indicating removal of the instrument fragment before placing the root-end filling.

(Courtesy Dr. Ryan Wynne.)

Intraradicular posts can be problematic in three ways relative to periapical surgery. Like other iatrogenic obstructions, they impede the use of nonsurgical revision techniques. Fortunately, modern technology makes it possible to remove most posts, but it is not always advantageous to do so. On occasion, the remaining tooth structure may be severely weakened, which will diminish the prognosis of the restored tooth even if the revision is successful (

FIGURE 16-23 A, Fractured post in a short root: a treatment planning dilemma. B, Post removal completed. Although necessary for restoration, removal resulted in a very large post preparation and thin dentinal walls.

Secondly, although removal of the post is usually the treatment of choice, it is seldom possible to determine the extent to which a post may be essential to the retention of a restoration. Treatment planning for periapical surgery is sometimes based on the conservation of satisfactory functional or esthetic restorations even if the post could be removed (

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses