The Adolescent Patient

Before reaching adulthood, every person passes through the stages of infancy, childhood, and adolescence. Adolescence is the developmental period between childhood and adulthood and is characterized by major physical, psychological, and social changes. Adolescence begins at the onset of puberty, a well-defined physiologic milestone that occurs as a result of increased levels of various hormones and results in significant physical growth and the development of secondary sexual characteristics. The initiation and completion of adolescence are highly variable among individuals. Humans have a prolonged adolescent development in which the conclusion is not defined by physiologic milestones, but by less clear-cut sociologic parameters that may vary widely among different societies.

THE ADOLESCENT IN THE WORLD

In our society, an adolescent must achieve several emotional or developmental milestones before becoming a psychologically normal functioning adult (Box 15-1). Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development describes the major event of adolescence as the identity crisis. During this phase, the adolescent must discover who he or she is and develop a unique identity, separate from family and other adults. According to this theory, the attainment of a realistic self-identity is a milestone for the passage into adulthood.

Stages of Adolescence

The psychosocial development of the adolescent can be divided into three distinct phases: early, middle, and late adolescence. During early adolescence, childhood roles are cast aside and dependent emotional ties with the family severed. The first signs of independence may occur when the adolescent becomes less involved and less interested in long-standing family activities and routines. It is common at this stage for the adolescent to bristle and become resistant when criticized or when given unsolicited advice by adults or authority figures. Within a short period, the once-obedient child may become rebellious and belligerent, heightening tensions and anxiety within the family. At times, the adolescent may be fearful of relinquishing the security of childhood and when stressed may revert to childlike behavior. To ease the transition into the early phase of adolescence, parents and other adults must recognize this assertion of independence as a part of normal development and when possible allow the teenager some degree of freedom of choice.

During the middle phase of adolescence, the teenager begins to seek a new identity through peer group involvement. New emotional ties with the peer group fill the psychological void left by the abandonment of childhood dependence on parents. Participation in peer group activities reinforces the sense of separation from parents and facilitates emotional separation from them. Adolescent groups may adopt outlandish clothes or styles to clearly differentiate themselves from their parents and other adults. Paradoxically, peer groups discourage individuality and the development of self-identity the adolescent must either conform to the ways of the peer group, or cease to be a member. At this stage, however, adolescents are not seeking a distinct identity but rather a stable one. Interpersonal relationships in the peer group are often superficial, and individual identity is highly compromised by pressures to conform to group standards. At the conclusion of middle adolescence, peer groups dissolve as individuality and self-identity increase. An adolescent with no friends, or poor peer group ties, may experience problems in facilitating the development of self-identity and independence.

In late adolescence, physical ties with the family are severed as the adolescent moves out of the home, becomes financially more self-sufficient, and accepts adult roles and responsibilities. With the eventual attainment of a stable self-identity and independence, the young adult accepts mature relationships with other adults without experiencing fear of losing control of his or her self-identity. Problems in these relationships may occur when an individual seeks to maintain peer group ties and/or family dependence.

Although these stages describe adolescent development in most North American and European families, considerable variation in the sequence may exist in other areas of the world. In many cultures, extended multigenerational families living together are the cultural norm. In some cultures, the passage into adulthood is clearly defined by a ritual passage or event. Once the adolescent has demonstrated completion of the rite of passage, acceptance as an adult member of the society occurs.

The Adolescent Population

Adolescents are a significant proportion of the U.S. population. In 2000, 14.5% of the total population or 40.75 million persons were between 10 and 19 years of age.1 Population projections for the United States predict that by the year 2010, the number of 13- to 18-year-olds will be 26.08 million or 8.68% of the total population. Between 2010 and 2025, the total number of 13- to 18-year-olds has been projected to show a modest increase, although decreasing slightly as a percentage of the total population.2 These projections are based on the expectation of a relatively stable birth rate and an increased life expectancy, resulting in an increased number of persons older than 65 years of age (Table 15-1). As a result, the size of the adolescent population will remain relatively stable, but as more people live longer, the proportion of the total population who are adolescents will decrease.

Table 15-1

Adapted from US Bureau of the Census: US Census 2000, Washington, DC, http://www.census.gov and Day JC: Population projections of the United States, age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1993 to 2050, US Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, pp 25-1104, Washington, DC, 1993, US Government Printing Office.

In developing nations, because of higher birth rates, a larger proportion of the population is composed of children and adolescents. Higher infant mortality rates and a shorter life expectancy also lead to a different distribution of ages in the population. Canada and Europe are expected to experience similar trends as the United States, with declining birth rates and an increase in life expectancy.

LIFESTYLE ISSUES THAT MAY AFFECT ADOLESCENT HEALTH

Diet and Nutrition

Significant physical growth occurs during the pubertal growth spurt. The age at which this spurt occurs varies among individuals. As a general rule, females tend to begin puberty and the growth spurt at a younger age than males. Proper nutrition is essential to ensure adequate growth during this period and to maximize genetically determined growth potential. In response to rapid growth, total caloric intake may be increased significantly. Although a nutritionally balanced diet is important, teenagers may develop poor nutritional habits by filling the increased demand for calories with a diet high in refined carbohydrates, fats, and salt. Peer group pressures may influence the type of diet an adolescent maintains. Increased social, academic, and leisure demands also may limit the amount of time a teenager has available to eat well-balanced meals in a home environment.

At-Risk Behaviors

Rejection of adult authority may cause some adolescents to abandon or show reduced interest in both oral and general preventive health practices. Pressures from peer groups may encourage teenagers to take risks by experimenting with tobacco, alcohol, or drugs. Peer pressures to engage in dangerous risk-taking activities with automobiles, bicycles, or skateboards may lead to physical injury. Injury is the leading cause of death in adolescence and plays a significant role in adolescent morbidity.3

Tattoos and body piercing have gained popularity among adolescents as a way to demonstrate independence and separation from the adult population. The jewelry associated with tongue and lip piercing may cause damage to teeth and create a source of intraoral infection. Some individuals may also go to extremes to modify the shape or appearance of the maxillary incisors. Radical changes in the shape of the incisors or the insertion of oversized poorly contoured metal crowns may increase the risk of periodontal disease and caries.

INFORMATION GATHERING

Confidentiality Issues

Practitioners must be aware that the relationship between dentist and adolescent patient is confidential, although situations can arise in which a breach of that confidentiality is ethically justified, such as when the patient poses an obvious threat to others or to himself. The discovery of information through history taking or physical examination may place the practitioner in an ethical dilemma with respect to the issue of disclosure to parents or legal guardians. During the course of treatment, the practitioner may gain information concerning sexually transmitted diseases, illicit drug use, pregnancy, or emotional disorders. In these situations, the dentist is not legally obligated to inform the parents or guardian of such findings. In some U.S. states, the law allows adolescents to receive treatment without parental consent for such conditions as sexually transmitted diseases and drug addictions.

To avoid the development of difficult situations, at the initial appointment the practitioner can discuss these confidentiality issues with the adolescent and parents or guardian. The adolescent can be informed that findings will not be disclosed without his or her knowledge, but that it may be in his or her best interest to disclose certain kinds of information to the parents so that they can be of support. The parents or guardian can then be advised that the practitioner is bound to respect the confidentiality of the dentist-patient relationship unless an immediate direct threat to the adolescent or to others is present. If the adolescent patient does become a threat to self or others and refuses to inform the parents or guardian, the practitioner should discuss the findings with the parents or guardian so that appropriate treatment or referral can be pursued.

If at some point, disclosure of other confidential information would seem to be in the patient’s best interest, the first step should be to frankly discuss with the patient the benefits of including the parents in planning for future treatment or referral. After this discussion, the adolescent should be given the chance to provide the information to parents or guardian. The dentist can offer to be present when the patient discusses these issues with the parent.

Patient History

With pediatric dental patients, parents or guardian provide the most if not all information gathered during the health history. Obtaining an accurate patient history for an adolescent requires tactful involvement of both the parents or guardian and the adolescent. The parent or guardian can be asked to supply the majority of the historical recall of past medical history for an adolescent. Surprisingly, however, some pediatric and adolescent patients may have a more accurate recall of events than their parents, so it is wise to have both parties present during the history taking.

With this age group, it is essential that the chief complaint be clearly stated by the adolescent and by the parents or guardian. Ideally the adolescent can be asked to articulate the chief complaint and treatment expectations in his or her own words at a time or location apart from parents or guardian. A major discrepancy may indicate differing expectations for treatment and treatment outcomes and, unless resolved, may lead to future conflicts between the parents or guardian, the adolescent, and the dentist.

Clinical Examination

As the patient evaluation process transitions from history taking to the physical examination, the dentist will typically gather information about recent growth changes and physical signs of puberty. The adolescent is asked to describe recent changes in height and weight, and current height and weight can be plotted on normal growth curves. Physical signs such as voice changes, presence of facial hair, initiation of menstrual cycles, and breast development can be used to evaluate whether puberty has begun or how advanced it is.

The process of completing a physical examination in the adolescent is identical to that used in adult patients. An extraoral and intraoral examination of soft tissue is completed along with an assessment of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) function and range of motion. The periodontal examination and dental examination are identical to those used for adults except that, in the adolescent, the examination may reveal the presence of newly erupted teeth. To screen for the presence of early onset periodontitis, periodontal probing is important, especially on first molars and incisors, the most commonly involved sites.

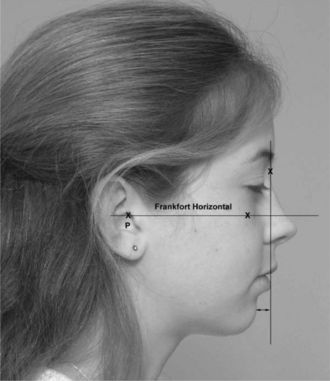

A reasonable radiographic survey for an adolescent patient includes a panoramic radiograph plus bite-wings. The panoramic image can be used to assess third molar development and the presence of any unerupted teeth. Bite-wings should be taken at appropriate intervals to assess the occurrence of proximal caries after posterior contacts have been established. During the transition between the loss of the primary teeth and eruption of the permanent teeth in the posterior segments, bite-wing radiographs are unnecessary if no proximal contacts exist. Since most definitive orthodontic treatment is completed in adolescence, general dentists should be well versed in assessing the need for orthodontic treatment in adolescent patients. Evaluate the frontal and lateral views to assess skeletal relationships. With the patient standing and looking forward, position the patient’s head so that the Frankfort horizontal (line joining the external ear canal and the infraorbital rim) is parallel to the floor. A vertical line dropped down from the nasal bridge (soft tissue nasion) can be used to assess maxillary and mandibular anteroposterior relationships (Figure 15-1). Discrepancies may indicate underlying skeletal disharmonies, which may require orthognathic surgery plus orthodontics to improve facial esthetics. Vertical skeletal relationships may also be evaluated at the same time. The mandibular plane angle (normal 30 degrees) can be estimated by the angle formed by the lower border of the bony mandible and Frankfort horizontal. Assess the symmetry of structures from the frontal view. The position of the chin button relative to the midsagittal plane can identify significant mandibular skeletal asymmetry, whereas observing the dental midlines relative to midsagittal plane can identify any dental arch asymmetry. If lip incompetence at rest is greater than 4 mm, a significant vertical skeletal discrepancy may be present or the incisors may be excessively proclined to accommodate the teeth. In such cases, extractions or orthognathic surgery may be necessary to reduce lip incompetence and incisor or gingival display.

Figure 15-1 Profile analysis using Frankfort horizontal (P-porion and O-orbitale) and the anteroposterior relationship of the mandible and maxilla in relation to a vertical reference line through the bridge of the nose.

Evaluate the dental arches for any overretained primary teeth, which may signify impacted or congenitally missing permanent teeth. The most commonly impacted teeth are the maxillary canines and the mandibular second premolars.

Overjet and overbite should be assessed. Excessive overjet usually indicates an underlying Class II skeletal relationship, whereas a negative overjet indicates a Class III skeletal relationship. A deep bite may result in stripping of palatal attached gingiva around the maxillary incisors, compromising their periodontal status. An anterior open bite usually indicates a skeletal vertical discrepancy that may require orthognathic surgery to correct if severity warrants.

Dental occlusion is then assessed as part of the orthodontic examination. Class II or Class III canine and molar relationships may indicate a skeletal discrepancy. In adolescents, dental malocclusions with an underlying mild skeletal discrepancy can be treated with growth modification or camouflage. Growth modification uses various appliances, such as headgear, to differentially control mandibular and maxillary growth. Camouflage relies on the extraction of permanent teeth to correct the dental malocclusion while masking the underlying minor skeletal discrepancy. To be effective, growth modification treatment for Class II patients requires a period of active growth. In late adolescence, if minimal further growth can be anticipated, treatment options may be limited to orthognathic surgery or extractions to camouflage the underlying Class II skeletal relationships. Treatment of patients with Class III malocclusions is usually delayed until skeletal growth is nearly complete. As mandibular growth does not cease until late adolescence or early adulthood, early treatment is avoided as patients may outgrow any final treatment results.

A posterior cross-bite with a functional shift of the mandible is indicative of a skeletal or dental transverse discrepancy. The correction of transverse problems is more easily accomplished with maxillary expansion appliances in early adolescence, as the midpalatal suture is less organized and less interdigitated than it will become in late adolescence or adulthood. After the suture has fused in adulthood, surgery is usually required to correct significant transverse problems.

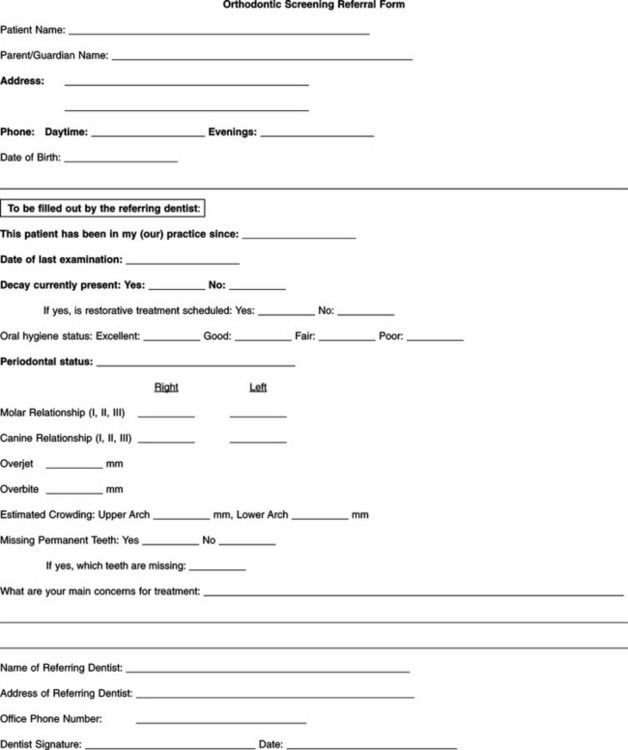

If skeletal or dental disharmonies exist, early adolescence or the late mixed dentition is usually an appropriate time to consider orthodontic intervention. Whereas many general dentists may consider undertaking adjunctive or limited tooth movement orthodontic treatment, most will elect to have an orthodontist treat patients with Class II or III skeletal malocclusions and Class I malocclusions with severe tooth/arch discrepancies. The Orthodontic Screening Referral Form (Figure 15-2) can be a helpful aid to the general dentist in both assessing the patient’s orthodontic needs and facilitating the referral to an orthodontist.

ORAL DISEASE IN THE ADOLESCENT

Dental Caries

Although dental caries has declined significantly in the adolescent population in the United States during the past 2 decades, some persons continue to be susceptible. Although many adolescents present with no caries or with only isolated pit and fissure caries, some individuals have rampant caries and are at high risk for new lesions. This latter group can be a major treatment challenge.

Several explanations for adolescent risk for caries can be identified. With the eruption of the permanent premolars and the permanent second molars, the number of susceptible occlusal and proximal tooth surfaces exposed to the oral environment increases. The crystalline structure and the surface characteristics of these newly erupted teeth make them more susceptible both to the initiation of caries and to the rapid advancement of the lesions once formed. The fact that adolescents often consume cariogenic diets and maintain less than adequate oral hygiene increases caries risk (see the What’s the Evidence? box).

Adequate plaque control is essential to the maintenance of good oral health. Effective oral self care has the dual benefit of creating an environment that is less conducive to the formation of carious lesions and more favorable to the maintenance of optimum periodontal health. Oral health instruction must be provided in a tactful manner that the adolescent patient readily accepts and implements. Just as important, the information must be perceived as relevant by the patient. The importance of good oral self care can be emphasized through discussion of the microbiologic basis of dental caries and periodontal disease. Informing the patient of the possible sequelae of poor oral home care including halitosis, painful teeth or gums, and unattractive or missing teeth will reinforce the perception of need for good oral self care.

For the patient who has a history of a high caries rate and is at risk for the development of new lesions, the dentist may recommend a diet analysis. Cooperation of both the parents and the adolescent is essential to obtain an accurate representation of dietary intake (see the In Clinical Practice: Diet and Nutritional Counseling for Adolescents box on p. 399). If after obtaining the diet history it is determined that changes are needed, it is often necessary to counsel both the parents and the adolescent in order to effect those changes.

Temporary sedative restorations can be a valuable tool in the overall management of an active caries problem. By excavating gross caries and placing interim restorations, the dentist can help arrest the caries process, creating an environment in which a preventive program can be effective. Before placing definitive restorations, adequate oral self care, diet control, and fluoride use must be established. Only after these key issues have been addressed should final restorative procedures be undertaken. If such an approach is not followed, in the near future the dentist will see an older adolescent or young adult returning with multiple new and recurrent lesions (see the In Clinical Practice: Management of Adolescents With High Caries Rates box).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses