Chapter 15

Postoperative care and periodontal maintenance therapy

Introduction

Active periodontal treatment should have a clear endpoint as its objective. It is important that an active diagnostic decision is taken to determine the satisfactory outcome of this treatment rather than simply enter a cycle of constant repetition of, for example, further courses of nonsurgical or surgical treatments. As discussed in < ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

Occasionally, it may be judged that achievement of these objectives may be compromised—for example, when compliance continues to be poor or if the patient continues to smoke. In these circumstances, it may be necessary to accept less than perfect outcomes and to arrange supportive periodontal therapy to try to reduce the risk of further disease in the future.

On completion of active periodontal treatment, two very important challenges remain for the clinician: (1) the management of any consequences of periodontal disease and (2) preventing the risk of recurrence of disease in the future. The aims of this chapter are to consider the management of some of the unwanted consequences of periodontal disease, to emphasize the crucial importance of establishing a maintenance programme for the patient, and to describe the requirements for a successful maintenance programme.

Managing the consequences of periodontal disease

Because periodontal disease causes tissue destruction that is largely irreversible, even following successful treatment, it causes a range of unwanted sequelae that can sometimes be more challenging to the clinician than the actual control of the disease per se. These sequelae are often the major concern of affected patients, and although it is important for the patient to understand the primary requirement of managing the periodontal disease, the clinician needs to take careful note of the patient’s concerns and to agree on a plan to address these.

The common consequences of periodontal disease that patients may complain about and that may require further management are listed in

Table 15.1 Patient-centred unwanted consequences of periodontal disease

| Consequence | Comments |

|---|---|

| Poor aesthetics | Due to recession, loss of interdental papillae (“black triangle disease”), tooth drifting and spacing, etc. |

| Dentine sensitivity | Due to root surface exposure from recession |

| Risk of root caries | Due to root surface exposure/dietary sugar intake |

| Tooth mobility | Resulting in compromised function/discomfort |

| Tooth loss | May require tooth replacement |

| Oral malodour (halitosis) | Periodontal disease is most common cause of oral malodour; should improve with active periodontal treatment; tongue brushing and mouthwashes may also help |

| Gingival swelling and bleeding | Should be addressed during active periodontal treatment phase |

A full discussion of the restoration of the periodontally compromised dentition is beyond the scope of this book. However, the cases presented here illustrate some of the issues that may arise and some management options available. In all cases, the management of the periodontal disease is the essential prequel to being able to address these problems, and as with all periodontal treatment, active maintenance programmes are required for long-term success.

Case 1

A 27-year-old man attended for review following previous treatment for severe localized periodontitis that had particularly affected the incisor teeth. He reported no problems with his gums, but he was deeply upset about the appearance of his upper anterior teeth, which had always been imbricated, but this appearance was now exacerbated by recent additional drifting and by gingival recession.

On examination, it was noted that he had responded extremely well to the previous periodontal treatment and there were no persisting pockets greater than 4 mm, no gingival bleeding, and plaque control was good. The upper anterior teeth showed marked crowding and imbrication, with UR2 retroclined and UL2 proclined, together with unevenness of the central incisors. The patient had an anterior open bite, and none of the teeth exhibited any increased mobility (

Fig 15.1 Case 1 (A) at presentation and (B) at extractions and fitting of immediate acrylic partial denture. (C) Teeth replaced with resin-bonded bridge with abutments at UL3 and UR3.

The teeth were carefully assessed, and although it was considered that following periodontal treatment their prognosis was good, the options for improving the aesthetics were limited. Because of the imbrication, there was loss of space overall for the upper incisors. Orthodontic treatment was not considered a suitable option in this case because of lack of space and the severely compromised periodontium of the teeth. Therefore, it was agreed that the only suitable solution would involve extraction of some or all of the teeth.

To assess further, study models were made and a range of options explored by diagnostic wax-ups, including extraction of upper lateral incisors and replacement with single pontic cantilevered resin-bonded bridges. However, because of the lack of space and the irregularity of the central incisors, it was agreed with the patient that extraction of all four incisors would give by far the best aesthetic result, recognizing that the central incisors would be made slightly narrower mesiodistally to allow for an even matching of the teeth. Consequently, the incisors were extracted and initially replaced with an immediate acrylic partial denture and finally replaced by a resin-bonded bridge using the UR3 and UL3 as abutments (

Extraction of the incisors was a major issue for the patient, but ultimately he was delighted with the outcome. Sometimes extraction of teeth is the right treatment not because they have existing disease but, rather, for overall aesthetics. In this case, the use of the upper canine teeth as abutments for the bridge was readily considered because these teeth were largely unaffected by the severe periodontal disease seen on the incisors and also because the occlusal loading on the bridge was relatively low, given the anterior open bite.

More generally, the decision regarding the use of periodontally compromised teeth as abutments for fixed or removable prostheses requires careful assessment. First, it is imperative that such teeth have been successfully treated for periodontal disease, but in these circumstances studies convincingly show that increasing occlusal load on teeth by using them as abutments will not result in renewed attachment loss provided that they are well maintained in a plaque-free state. However, the increased occlusal load on an already compromised tooth can further increase tooth mobility. Thus, when determining whether to use a periodontally compromised tooth as an abutment, consideration has to be made regarding the magnitude of the likely increased occlusal load to which it will be subjected, if it is possible to spread the load over a number of abutment teeth, and in the most extreme cases, whether to incorporate “cross-arch bracing” to prevent mobility of prostheses.

Case 2

A 46-year-old woman with generalized severe chronic periodontitis that had been successfully treated complained of marked mobility, particularly of UL1, and some spacing of the upper incisors. She has good plaque control but is a smoker of approximately 10 cigarettes a day. She is committed to trying (again) to quit smoking.

On examination, the UL1 showed grade 2 mobility and the UR1 grade 1 mobility. The patient reports the UL1 is uncomfortable, particularly on eating, and thus affects her masticatory function. She is always concerned about “catching” the UL1 during function and making it even more mobile.

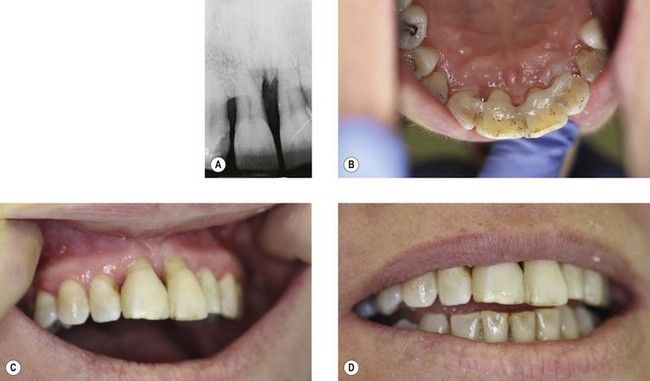

The mobility was managed by the use of a fibreglass-reinforced composite splint applied to the incisors, and the contour and spacing of the teeth improved by composite buildups (

Fig 15.2 Case 2. (A) Radiograph of upper central incisors showing severe bone loss, particularly at UL1. (B) Fibreglass-reinforced splint placed on incisors. The splint has had to be placed quite apically to avoid occlusal interferences, and it requires very careful maintenance because of the increased risk of plaque accumulation. (C and D) Labial view of splinted teeth. Composite buildups have been placed as part of the splint to improve contours of teeth, particularly at UR1 distal and UL1 mesial.

Acid-etch bonded composite materials are very useful in managing some spacing and dri/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses