14

The Link Between Orthodontics and Prosthetics

Introduction

Edentulousness and space management: the mesiodistal dimension

Unilateral agenesis of the maxillary lateral incisors

Bilateral agenesis of the maxillary lateral incisors

Prosthetic solutions

Bonded prostheses

Protocol and guidelines for successful placement of a resin-bonded bridge

The implant option

Frequency of use of the implant solution as an indication of its suitability

The vertical dimension

Uprighting the dental axes

Tissue remodeling

Orthodontic extrusion technique

Orthodontics, periodontal disease and prosthetic splinting

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

Introduction

The development of age-specific orthodontic mechanics and techniques has significantly influenced the contribution of orthodontics within the framework of a multidisciplinary approach. It is even seen as being indispensable in some cases of complex edentulousness in which purely prosthetic solutions would be difficult to implement without orthodontic assistance (Fig. 14.1). Moreover, in adults, orthodontics can be called on to treat either primary malocclusions which have remained unrecognized since infancy or to help decisively in reducing secondary tooth migrations following periodontal disease. Furthermore, over the past two decades, clinical practice has been marked by significant developments in non-invasive prosthetic solutions owing to two underlying causes:

- Improved knowledge of the physico-chemical data and of the mechanics of adhesion which, combined with more effective bonding polymers, has given a new lease of life to the bonded bridges described by Rochette (1973)

- Adoption of the sound osseointegration principles introduced by Brånemark et al. (1985) has enabled implantology to offer a first-line treatment solution for all types of edentulousness.

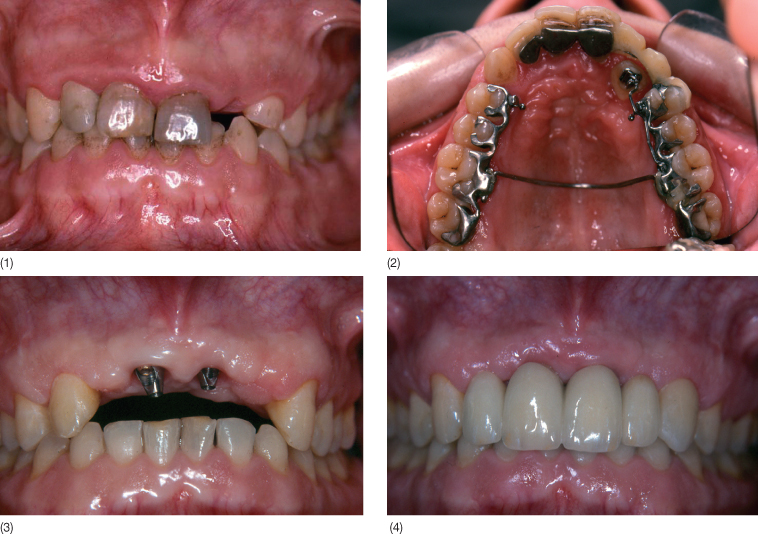

Fig. 14.1 (1) Clinical situation illustrating the indispensable contribution made by orthodontics. This adult patient suffered a traumatic blow during his teens resulting in the loss of the four maxillary incisors. Three of the four teeth were reimplanted. During a preliminary clinical examination, we found a persistent deciduous canine and evidence of an impacted permanent canine. (2) A multidisciplinary approach was adopted. The orthodontist (A Fontenelle) extruded the impacted canine and repositioned it into the arch. Without the assistance of orthodontics, the final prosthetic treatment (implant-supported bridge) would not have been possible, as the impacted canine would have constituted an anatomical barrier. (3) Once the canine was in position in the arch, the reimplanted teeth were extracted, thus freeing the implant site. The implant solution was optimized by placing two implants at 11 and 12 (surgery: MP Daossans). Placement of a fixture at 22 and 12 would have been possible but the implant would have emerged in the embrasure between the lateral and central incisor, thus rendering the prosthetic solution more complex. Angulated components rectified the implant axes and facilitated placement of a screw-removable prosthetic system. (4) Final view of the prosthesis. A veneer was placed on the unprepared canine to enhance the final aesthetic appearance. (Laboratory work: J Ollier.)

However, the implementation of these non-invasive treatment options often requires a harmonious distribution of the edentulous spaces, a situation in which the orthodontist has a vital role to play. Orthodontic pre-analysis aims to determine the degree of harmonization required to correct dental or dentomaxillary disorders and to indicate whether prosthetic compensation is needed and what form it should take. In this chapter treatment of edentulousness due to agenesis and trauma has been chosen to highlight the contribution of orthodontics to space management. Tissue remodelling and the correction of secondary tooth migrations in patients with periodontal disease will also be described to illustrate the importance and benefits of orthodontic treatment in multidisciplinary treatment plans.

Edentulousness and Space Management: the Mesiodistal Dimension

Space management represents the field of closest cooperation between orthodontist and prosthodontist. The most frequent instance of this coordination involves agenesis, particularly of the lateral incisors, on account of its relative frequency of occurrence and because it is often discovered incidentally in patients with no dental lesions. The problem it causes is two-fold, both esthetic and functional. The treatment principles described here can serve as a basis for the different clinical forms of agenesis. Previously, orthodontists would most often opt for space closure in order to avoid premolar extractions and the organic mutilation associated with ceramic-metal bridges. More recently, since the early 1980s, the combination of orthodontics and bonded prostheses in treatment using space opening in patients with agenesis of the lateral incisors has become common practice (Samama 1986; Samama et al. 1993).

Unilateral Agenesis of the Maxillary Lateral Incisors

Currently, space closure should not be used to treat unilateral agenesis of 12 or 22, except in exceptional cases, because an approach results in esthetic and functional disharmony. Moreover, except in unusual clinical circumstances, one should avoid extraction of the contralateral lateral incisor followed by bilateral closure of the spaces.

Currently, with some exceptions, space reopening before prosthetic treatment is the generally adopted solution on account of its non-invasive nature. It is possible to fabricate a fixed prosthesis with minimum mutilation of the natural dentition, allowing greater esthetic harmony as well as balanced function with the establishment of symmetrical anterior guidance. In this approach, orthodontic treatment combines:

- Functional placement of the canine

- Creation of sufficient space to accommodate a cosmetic replacement for the missing lateral incisor

- Creation of minimum space palatally when the bonded bridge option is chosen (Fig. 14.2) in order to limit dental mutilation as far as possible. The implant option with its particular requirements is described in the section on bilateral agenesis below.

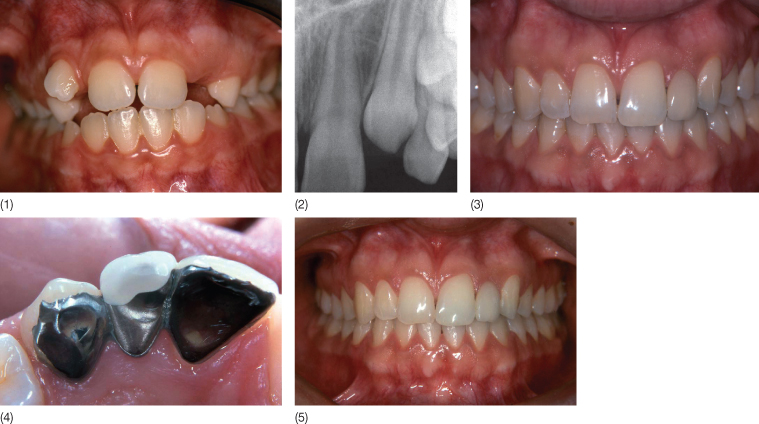

Fig. 14.2 (1) A patient with unilateral agenesis of the maxillary lateral incisor. The aim of orthodontic treatment, initiated in 1987, was the harmonious positioning of the teeth in the arch as well as space opening. (2) X-ray confirming the absence of the lateral incisor. (3) In 1996, a bonded bridge was inserted to compensate for the missing lateral incisor (laboratory work: J Ollier). (4) Palatal view of the bonded bridge. (5) Clinical view in 2004. Note the preservation of esthetic integration and absence of negative influence in spite of the vertical eruption and buccal version in relationship with late growth often observed in adult patients.

Bilateral Agenesis of the Maxillary Lateral Incisors

Two solutions are currently available to the orthodontist for bilaterally missing upper lateral incisors: a purely orthodontic approach with space closure or an ortho-prosthetic approach involving space opening and the use of prostheses to replace the missing incisors. The choice is made taking into account any possible work needed to correct anomalies related to the condition. It may also depend on the patient’s motivation, their esthetic requirements and the scope and length of the treatment.

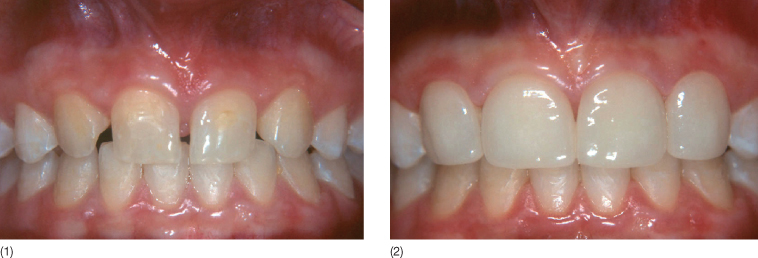

Space closure is still a good option as it allows definitive compensation of the dental deficit by adolescence. In addition, this approach requires the intervention of only one specialist, the orthodontist. It is indicated in cases where tooth size–arch length discrepancy is associated with the agenesis. In this case, space closure enables treatment of this discrepancy, thus avoiding premolar extractions. This option can also be considered in clinical situations in which the canines display a low mesiodistal index (a flat morphology and an abraded free margin). If this is not the case, and in the presence of an unsightly canine, this treatment choice will often need to be accompanied by coronoplasty, or canine crown sculpting. This (often difficult) procedure transforms the canine into a pseudo-lateral incisor by reduction of the crown or addition of composite or a veneer (Dietschi and Schatz 1997; Samama and Ollier 2002) (Fig. 14.3).

Fig. 14.3 (1) Patient with agenesis of 12 and 22. (2) Space closure followed by veneers bonded on non-prepared teeth according to the protocol described by Samama (laboratory work: J Ollier).

Robertsson et al.’s (2000) retrospective study of 50 patients (36 women, 14 men) representing 39 cases of bilateral agenesis deserves consideration: 93% of the patients with canines in the lateral incisor position (space closure) were satisfied with their appearance whereas only 65% of prosthetically rehabilitated patients expressed satisfaction. This observation highlights that an attractive, successful anterior restoration is probably still the prerogative of the specialist. Moreover, there are arguments which have long been used to contraindicate space closure, in particular, the absence of canine function.

This notion is no longer as urgent as it once was, especially since Slavicek (1983) showed that canine function does not necessarily result in extensive posterior disclusion and emphasized the important role of canine function in lateral disclusion. It is therefore down to the orthodontist to ensure lateral disengagement of the mandible on the buccal cusp of the first premolar either by applying torque or by grinding the palatal cusp. Opening of the subnasal angle resulting in an unesthetic profile: from a dental point of view, torque delivery using a fixed technique provides upper lip support if the maxilla is not moved back en masse, but does not provide support to the nasal-cheek fold in the event of mesial drift of the canine eminence. The patient’s refusal to wear a prosthesis or his/her lack of enthusiasm for combined treatment constitute indications for orthodontic treatment alone.

However, other arguments plead against space closure (Samama 1986, Samama et al. 1993, Millar and Taylor 1995, Balshi 1993, Richardson and Russell 2001):

- Esthetics: Current esthetic criteria advocate a convex face, a prominent mouth and the absence of dark buccal corridors during smiling. Indeed, the maxillary teeth make a distinct contribution to dentofacial harmony, whereas the lower teeth generally go unnoticed and pose fewer esthetic problems. Hence, according to Canut (1996) current dentofacial criteria are based on three essential factors: the profile convexity, the sub-nasal angle and the chin contour. The patient’s wishes and motivation as well as the need to pre-empt any potential future esthetic grievance should be taken into account. It should be noted that the gender of the patient may also influence the choice of treatment since girls are often more aware of esthetic issues than boys.

- Class III malocclusions

- Canine shape, when the latter is very unfavorable

- Patient’s wishes.

When treatment involves space opening, a continuous dental arch is restored by means of prosthetic devices. Most often, the treatment plan is multidisciplinary in that the necessary prosthetic space needs to be planned with the orthodontist.

The advantages (Samama 1986; Millar and Taylor 1995) are: the preservation of the Class I relationship, maintenance of canine function, support for soft tissue, reduction in the risk of bone/joint-related complications and the re-establishment of esthetic harmony. The large number of team members involved makes for more complex and more expensive treatment. Scrupulous oral hygiene must be maintained, given the risk of a debonded bridge or, with implants, of possible deterioration of the mucosal environment.

Prosthetic Solutions

Prior to choosing a prosthetic solution, thought should be given to the timing of interception. Indeed, the placement of an implant in a young still-growing patient can prove tricky and can even be contraindicated particularly in the area of the lateral incisors (Thilander et al. 1992). Similar to reimplanted or ankylotic teeth, the fixed implant position will give rise to vertical discrepancy in relation to the adjacent teeth (Odman et al. 1991; Westwood and Duncan 1996). Brugnolo et al. (1996) observed that single-tooth implants in adolescents are infraoccluded in comparison with the natural neighboring teeth. Significant changes affecting esthetic appearance were also noted in this study in connection with the peri-implant mucosal environment. A few authors (Cronin et al. 1994; Westwood and Duncan 1996; Spear et al. 1997) claim that the prognosis of implant-supported restorations is easier to predict after the age of 15 for girls and 18 for boys. Currently clinical hindsight would appear to show, however, that it is wiser to take into account dental and skeletal maturity rather than actual patient age (Thilander et al. 1994). The aim of orthodontic treatment is not only to open up sufficient space in the implant area but also to achieve optimum occlusal stability in order to reduce the risk of infraocclusion of the implant-supported crowns (Thilander et al. 1999).

Adults can also exhibit major changes in the alveolar region, although these are usually less rapid than in younger patients. Such changes appear, however, to be sufficiently extensive to alter, with time, the peri-implant mucosa possibly requiring a new prosthetic device (Oesterle and Cronin 2000). Thus, Bernard et al. (2004) have demonstrated that mature adults (40–55 years) may display major vertical discrepancies in relation to their osseointegrated implants similar to those observed in young patients who still possess growth potential. Moreover, delaying the implant approach does not seem to impact the available bony volume after orthodontic treatment.

Kokich and Spear (1997), in a study performed with 20 patients, reported a 1% bone loss in the lateral incisor region 4 years after completion of orthodontic treatment. In comparison, tooth extraction induced a 34% bone loss after 5 years according to Carlsson et al. (1967). It appears, therefore, that the bone created by space opening is stable over time (Kokich and Spear 1997; Spear et al. 1997).

Bonded Prostheses

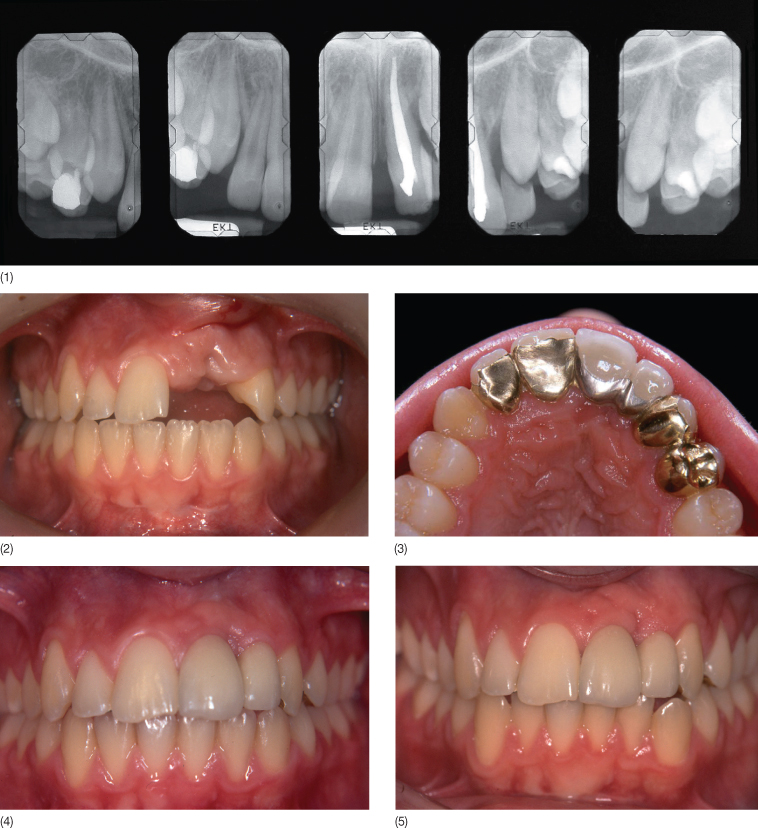

The bonded prosthesis (Samama 1986, 1995; Samama et al. 1993, 2005) appears to offer the solution of choice for children and adolescents (Fig. 14.4) and young adults. Compared with conventional fixed prostheses it has the advantage, of leaving supporting teeth virtually untouched as the preparations are placed exclusively on the enamel. It also allows treatment in situations where, despite orthodontic therapy, crown space is still limited and associated with root convergence which has not been fully corrected (Figs. 14.5 and 14.6). However, it requires close observance to procedural details, which can vary according to the clinical circumstances (see next section).

Fig. 14.4 (1,2) Patient with a reimplanted traumatized central incisor and agenesis of the lateral incisor. Compromise orthodontic treatment was aimed at redistributing the spaces (it was necessary to extract the reimplanted central incisor). (3) The bimaxillary protrusion was preserved in order to avoid extraction of the premolars. The end-of-treatment occlusion–joint relationship was very favorable for the placement of a bonded bridge (orthodontic work: A Fontenelle). Palatal view in 1995 of the restoration using two removable pontics. (4) Labial view of the restoration in 1995. (5) Labial view in 2004. Note that the bridge splint has fulfilled its role perfectly as a replacement and as a retainer. In contrast, it would have been preferable to make a bonded retainer in the lower arch to avoid tooth movement, given the unstable occlusion.

Fig. 14.5 (1) A patient with agenesis of the lateral incisors treated in 1986. Orthodontic treatment (A Fontenelle) was undertaken for space opening. Note the reduced mesiodistal space is inadequate for implant treatment. (2) Trying in the bonded bridges. (3) The clinical situation 9 years post treatment (laboratory work: J Ollier). Note the grayish hue of the teeth due to the metal bridge on the palatal aspect. Opaque Meta 4 resin (Superbond) did not exist at the time.

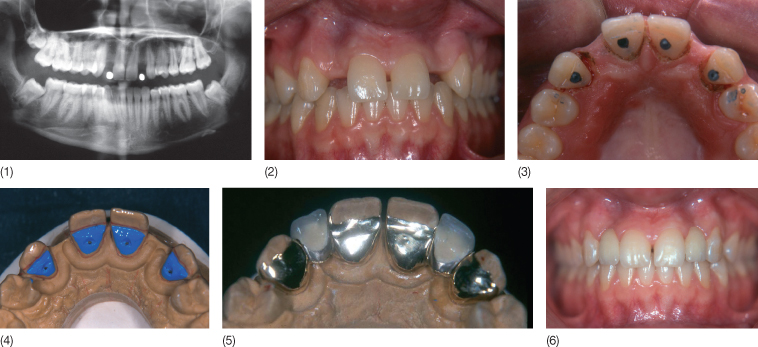

Fig. 14.6 (1,2) Intraoral view indicative of radicular convergence, contraindicating implant therapy in a patient with agenesis of 12 and 22. Note the thinned alveolar ridge, pointing to bone hypoplasia. Radiographic examination (1) confirmed insufficient bone volume. (3) Micro-preparations (pins) were carried out to increase retention. (4,5) View of the working model: note that the preparations avoid the occlusal area. (6) The prosthesis: the pontics were first independently constructed and then incorporated into the bridge (laboratory work: J Ollier).

Protocol and Guidelines for Successful Placement of a Resin-Bonded Bridge

Surface Treatment of Enamel and Dentine

Enamel

In order to allow adhesive penetration and significant adherence values (from 15 to 20 mPa), the enamel surface must be etched with a 40% orthophosphoric acid solution for 45–60 seconds. The surface treatment is followed by copious rinsing with water for 60 seconds and then air-drying.

Dentine

Adhesion to dentine is less critical inasmuch as the resin-bonded bridge design emphasizes the polymer/enamel bonding interface. However, the micro-preparation process for the abutment teeth exposes the dentinal surfaces, which need to be treated. What we know concerning the involvement of the hybrid layer (Nakabayashi et al. 1982) in the improvement of the bonding process indicates the need for:

- Elimination of the smear layer

- Superficial decalcification of the dentine without denaturing the collagenous proteins

- Impregnation of collagen fibers with a monomer containing reactive groups that give this substrate a certain affinity.

In this respect, the combination of preliminary treatment with a citric acid and ferric chloride solution and an appropriate adhesive (4META/MMA) gives effective results.

Choice of the Adhesive

Since 1983, we have used a chemically activated resin, 4META/MMA TBB (SuperBond® Sun Medical), which has the following characteristics:

- The monomer contains 5% 4-methacryloxyethyltrimellitate anhydride (Takeyama et al. 1978)

- The catalyst, developed by Masuhara et al. (1963, 1984) is tri-butylborane, which is the only member of its class that has the advantage of being activated and not inhibited in the presence of oxygen or humidity

- The polymer powder is a methylpolymethacrylate resin that has been widely used for decades in odontology

- The adhesive has rheological properties that allow stress absorption and dissipation by viscoelasticity

- The adhesive demonstrates good biocompatibility and, according to histological studies, does not elicit a severe dentino-pulpal reaction (Yamami et al. 1986; Matsuura et al. 1987)

- Esthetic problems due to the dark metal giving a grayish appearance to the incisal third of the abutment teeth are also resolved by adding opaquers to the formerly translucent resins.

Selecting the Alloy

The need for a stiff low-thickness alloy able to support masticatory forces without distortion and rupture led us to favor class III gold alloy. The pontic we use is removable and is a classical ceramic fused to metal device. The sub-structure of the resin-bonded bridge is first subjected to alumina sandblasting (Dijkman and Arends 1986) and secondly, treated with a silane deposit. The use of a silane-based (ethyl tetra-silicate) primary, vaporized under heat (130°C), creates a deposit of approximately 0.1 mm. This film, covered by a coupling agent, allows for chemical retention with different adhesives (Silicoater-Silicoup system). Silanization provides metal-adhesive bonding that is superior to that of the adhesive material alone. Some manufacturers also propose the use of cooled silane primers.

The Rocatec (3M-Espe) system is the most up-to-date system in which the silica deposit is formed by tribochemical reaction. The intrados is first sanded with aluminum oxide particles followed by silica-coated alumina. The silica adheres due to the thermal energy produced by the transformation of mechanical energy. Appliances are also available in the shape of pistols/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses