Chapter 14

Problem-Solving Techniques for Revision of Previous Root Canal Procedures

Problem-solving issues and challenges in the revision of previous root canal procedures addressed in this chapter are:

“Whenever a pulp is removed and the canal treated and filled in a manner that is compatible with or favorable to a physiologic reaction, we may expect a satisfactory percentage of success. Also, whenever treatment is carried on in such a way as to antagonize biologic processes of repair, we will continue to have many failures.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

“If by accident, the instrument used should break—and this is an accident careful handling should make very rare—it will sometimes be found difficult, and it may be impossible, to remove. If not jammed in the fang so as to be immovable, it may, in many cases, be withdrawn by rendering a small instrument magnetic, and passing gently up till it comes into contact with the fragment to be removed. The use of a magnetized instrument was suggested some time ago by the late Dr. John Harris, for a similar purpose. Once or twice during my practice I have found it impossible to remove the broken fragment of the instrument from the fang, and was obliged to fill without regard to it. I have observed no unfavorable results in these cases which I could attribute to this cause.”

Unfortunately, the need for revision of previous nonsurgical (and surgical) root canal procedures is quite common in today’s practice of endodontics. The number of these cases can be largely reduced, however, if adherence to the principles of technical excellence provided in this book is a priority during the initial treatment.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide guidance in the techniques for successful revision of failed nonsurgical treatment.

Recommendations for Removal of Existing Restorations

Root canal treatment in general, whether initial treatment or revision, does not usually require the removal of existing crowns. It is in the best interests of the patient to preserve satisfactory restorations, but if by doing so, the ability to revise the previous root canal treatment is compromised, it behooves the clinician to treatment plan the dismantling of the restoration. Similarly, while it is wise to make access cavities as conservative as possible, the access cavity should not be so small as to compromise access to the root canal system and perhaps the quality of the revision. Excessively large access cavities, on the other hand, undermine the retention of existing and usually satisfactory fixed prostheses. In most cases, the size of the access cavity should be the same as one would make for initial treatment.

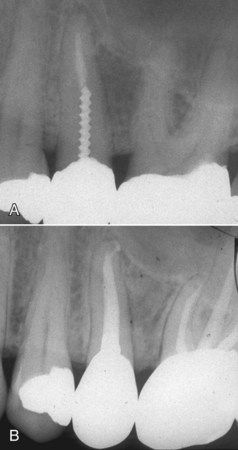

Revision of root canal treatment can sometimes be accomplished while preserving existing posts and cores as well. Knowledge of internal tooth anatomy will provide avenues of success without the necessity of post removal. Anatomically wide canals such as the distal canals of mandibular molars or the canals of maxillary second premolars typically have a morphology a preformed stainless steel post will not completely obliterate (

FIGURE 14-1 A, Cross-section of a typical maxillary premolar showing unprepared canal space that might be available to bypass an existing post during revision. B, Symptomatic maxillary premolar with inadequate root canal treatment. C, Revision in progress without removal of existing restoration.

Second, in a multicanal tooth, the canal in which the post was placed may not need revision. Again, it may be possible to access a canal with recurrent pathosis or a canal that was previously uncleaned without removing the entire restoration.

FIGURE 14-2 A, Inadequate root canal treatment and recurrent apical pathosis in mandibular first molar. Note the post is in the distal buccal root, which has no apical lesion. B, Completed revision of three canals without removal of the cast post-core.

Crown or restoration removal becomes a necessity when recurrent caries is found to extend well under the crown margins and is often in fact the etiology of periapical pathosis. A simple method for removing a full crown is seen in

FIGURE 14-3 A, Crown indicated for removal due to recurrent caries under margin. B, Beginning at the buccal gingival margin, the crown is cut up the buccal surface and across the occlusal-lingual aspect. Note the underlying tooth structure is not cut. C, Large, flat instrument such as an operative chisel or surgical elevator is used to pry the crown away from the tooth. D, Crown removed.

Removal of Restorative Materials from the Pulp Chamber

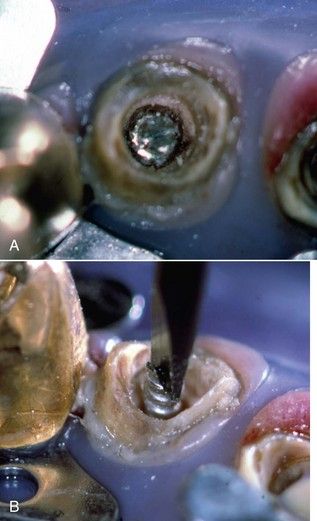

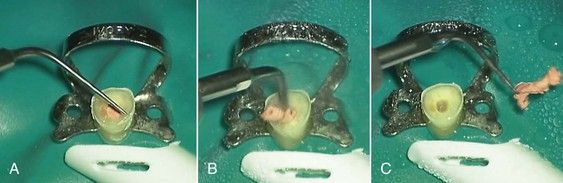

Although standard round and fissure burs are typically used for this procedure as the access preparation extends into the pulp chamber, there is an inherent risk of cutting excessive tooth structure and weakening the tooth. If the pulp chamber is restored with amalgam or composite resin, there is no alternative but to carefully dissect this material with high-speed burs. If, on the other hand, the pulp chamber is found to be filled with a cement such as Cavit (3M ESPE Cavit Temporary Filling Material, St. Paul, MN, USA), zinc oxyphosphate, or zinc oxide eugenol, an ultrasonic handpiece will efficiently remove the restorative material with little effect on the dentinal walls. The ultrasonic tip of choice is usually a prophylaxis tip or a probe shaped tip (

The ultrasonic technique is especially useful if the root filling material has a core carrier or is composed of metal. A bur will cut these materials and eliminate the potential to retrieve them using a forceps-type instrument. The removal of zinc phosphate cement from the pulp chamber with the ultrasonic instrument is seen in

FIGURE 14-5 A, Demonstration case: silver cones embedded in zinc phosphate cement. B, Removal of zinc phosphate was done with the probe-type ultrasonic tip. The cement was removed completely in 3 minutes without damage to silver cones.

Techniques for Removing Intraradicular Posts

Intraradicular posts are used routinely in restoring severely carious or fractured teeth (see

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

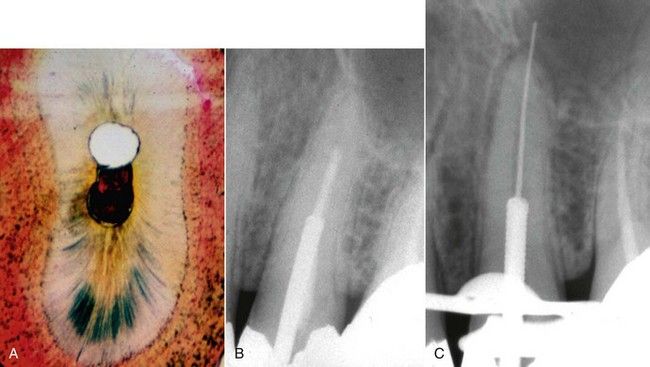

A 43-year-old male presented with symptoms that focused on the maxillary left second premolar area. He stated that the tooth had had root canal treatment and a post and crown, and he could not understand why he was now having a problem. The tissues were slightly swollen in the midroot region of this tooth. Radiographically, there was evidence of root canal treatment with a post and the presence of a large lateral lesion (

Solution

Through a routine occlusal access opening, the composite resin surrounding the post was carefully removed, and the post was subjected to ultrasonic vibration with the probe type of tip described above. Revision was completed, and a 7-month reexamination of the patient indicated that the tooth was in full function; radiographically, healing of the lesion was apparent (see

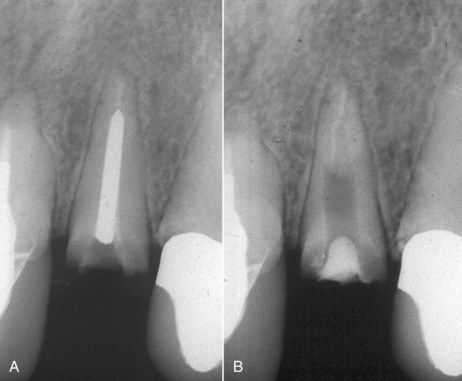

Although it is possible to remove almost any post with the current technology, the tooth may become so mutilated in the process, prognosis is questionable. For example, after post removal, a short root with thin walls has little hope for a long-term viable restoration (

FIGURE 14-7 A, Inadequate root canal treatment in a maxillary lateral incisor with a fractured post. B, Successful removal of the post, but a very weak tooth remains. Treatment planning may warrant the consideration of an implant.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

A 55-year-old male presented with a fractured post in the maxillary right second premolar. In addition, the root canal treatment was less than acceptable, resulting in recurrent periapical pathosis (

Solution

Following a thorough discussion of the treatment options and potential outcomes, the patient opted to retain the tooth. The post was removed using ultrasonic techniques, and the root canal treatment was revised. The root canal was filled slightly short of the divergent apical canal walls using a custom-fit gutta-percha cone and a root canal sealer that included mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) powder (see

Fractures of intraradicular posts are typically observed to occur at or just below the cavosurface margin of the post preparation. They appear to be the result of metal fatigue, not unlike continuous bending of a piece of wire (like a coat hanger) that breaks eventually. In almost all cases of post facture, it is also observed that there was minimal extension of the crown margin past the post/core buildup onto tooth structure. This is often referred to as lack of a ferrule. Several examples are illustrated in

With the availability of ultrasonic devices, removal of intraradicular posts has become much easier, and there is less risk of physical damage to the root compared with levering types of post removers or pullers. In addition, specialized tips are available designed to apply energy to the post.

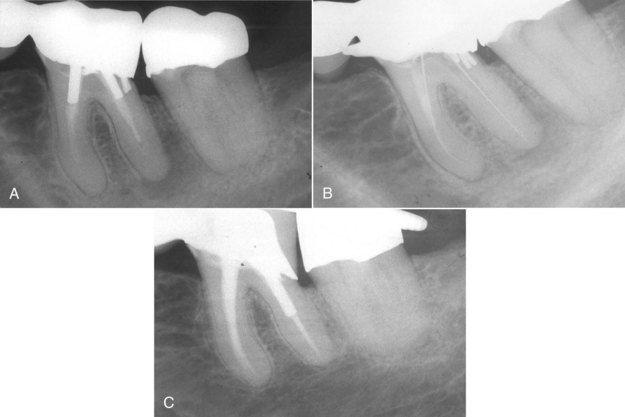

Posts can be removed successfully from the inside of full crowns in molar teeth, as illustrated in

FIGURE 14-9 A, Mandibular first molar bridge abutment with inadequate root canal treatment. Clinically, a drainage tract had been present for months. B, Following removal of two posts and renegotiation of the canals. C, Reevaluation after 1 year, indicating complete periapical healing.

If the post cannot be removed with ultrasonic application only, a Masserann trephining bur (MicroMega SA, Besançon, France)

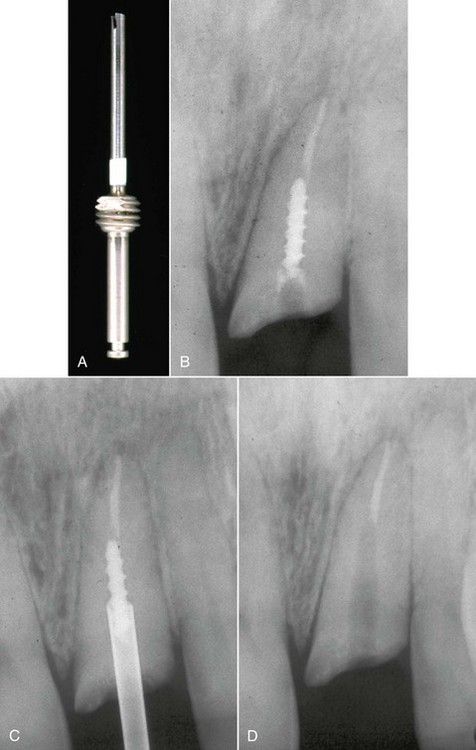

FIGURE 14-10 A, Masserann trephining bur. B, Fractured post in a maxillary lateral incisor. C, Use of the trephine to create space around the post prior to application of ultrasonic instrument. Approximately half the post length must be exposed for successful removal. D, Post removed.

In the case of fractured posts, access is no problem, but the margins of the fractured end of the post must be troughed with a half-round bur or the ultrasonic instrument in advance of the trephine. With copious irrigation, frequent pauses to clean the bur, and slow penetration, a space is created around the post fragment to a depth of approximately half the post length. During use, it is important to inspect the bur for flaring and to resharpen it. Since the post is metal, there is no danger of cutting into it or of straying from it into the root. The drilling normally will take between 5 and 10 minutes.

Once the space has been created around the post, the ultrasonic device is used on the maximum setting with a vibrating tip against the exposed end of the post.

Occasionally the most difficult part of post removal is getting the loose post fragment out of the canal because of the very limited space around it and the lack of post material above the occlusal surface on which to grasp with an instrument. The usual approach is continued ultrasonic vibration.

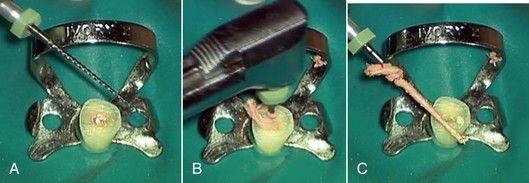

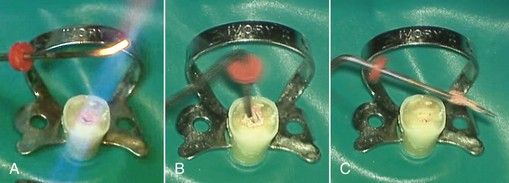

Another option that can be used with fractured threaded posts is a combination of ultrasonic vibration and cutting a slot across the top of the post to serve as purchase for a small screwdriver. The slot can be made with a No. ![]() to 1 round bur or 33

to 1 round bur or 33![]() inverted cone. A small jeweler’s screwdriver is placed in the groove, followed by application of ultrasonic vibration. Pressure is applied in a counterclockwise fashion on the screwdriver during vibration (

inverted cone. A small jeweler’s screwdriver is placed in the groove, followed by application of ultrasonic vibration. Pressure is applied in a counterclockwise fashion on the screwdriver during vibration (

Removal of Soft Root Canal Filling Materials

Techniques for Removing Gutta-Percha

Large Canals

Hedström File Technique

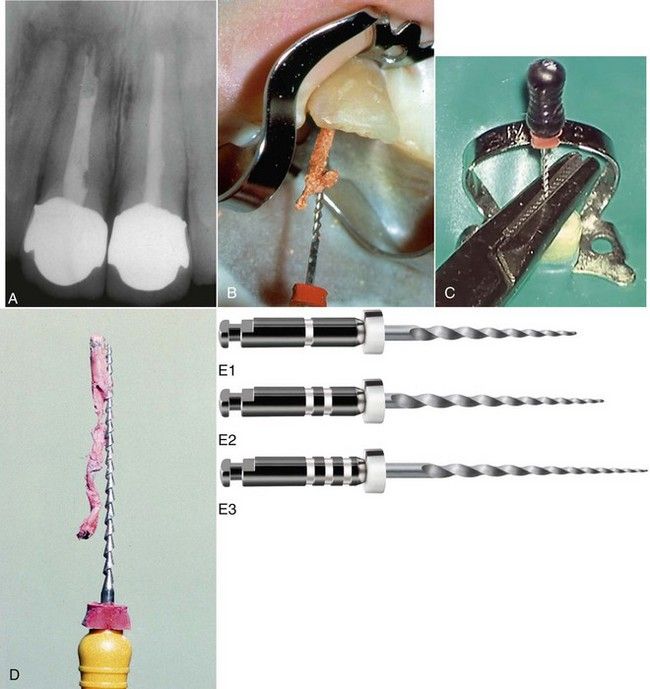

When the need for treatment revision is identified in the case of a poorly obturated, relatively large diameter canal, such as the maxillary central in

FIGURE 14-12 A, Inadequate root canal treatment in a maxillary right central incisor. B, Removal of gutta-percha in one piece with a large Hedström file. C, File retrieval assisted with a surgical needle holder. D, Hedström file with removed gutta-percha. Note the fluting of the file is ideally designed to engage the filling material on withdrawal. E, Nickel-titanium rotary instruments for gutta-percha and paste removal.

(E courtesy Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties, Tulsa, OK, USA.)

Small Canals

The Hedström file technique is also viable for small canals but is unlikely to remove the entire filling in one piece, and the smaller-diameter files required are more prone to fracture if they are screwed into the gutta-percha. To devise a plan for removing gutta-percha from small canals, no one hand-instrument technique is effective or recommended to clear the entire canal. It is helpful to consider which techniques are more useful in the coronal half of the canal and which are more appropriate for the apical half, especially in the presence of curves.

Gutta-Percha Removal in the Coronal Half of Small Canals

Rotary Nickel-Titanium Technique

Nickel-titanium (NiTi) files normally used for canal preparation can be used for gutta-percha removal as well.

Heat Technique

Heated instruments have been recommended to remove the gutta-percha from the orifices and coronal third to half of the canal space (

Ultrasonic Technique

Currently available ultrasonic units designed for endodontic use possess enhanced energy to soften even old, hardened gutta-percha material (

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses