CHAPTER 14 Pharmacologic Management of Patient Behavior

FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS

In contrast to this awake state, deep sedation and general anesthesia are defined as conditions of the patient characterized by an incomplete, partial, or total loss of protective reflexes. In addition, there may be a partial or complete loss of the ability to independently and continuously maintain a patent airway. Cardiovascular function may also be impaired. Under these circumstances, the patient is noninteractive and does not respond purposefully to physical stimulation or verbal command.

ANATOMIC AND PHYSIOLOGIC DIFFERENCES

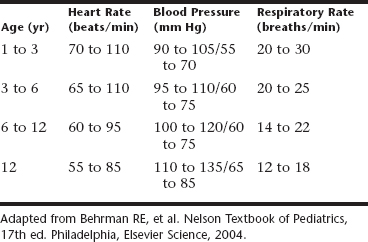

When a regimen of sedation for the pediatric patient is prepared, it is important to consider the differences between the adult patient and one in the pediatric age group. The sedation of children is different from the sedation of adults. Differences in size, weight, and age as a measure of maturation of systems are obvious. Less obvious, but equally important, are the differences in basal metabolic rate between the adult and pediatric patient. Basal metabolic activity is greater in children, which ultimately affects not only drug response but also important physiologic parameters as well. Because oxygen demand is greater but the alveolar system is less mature, the respiratory rate is far higher in children than in adults (Table 14-1). This is an important consideration when drugs that depress the respiratory system are administered.

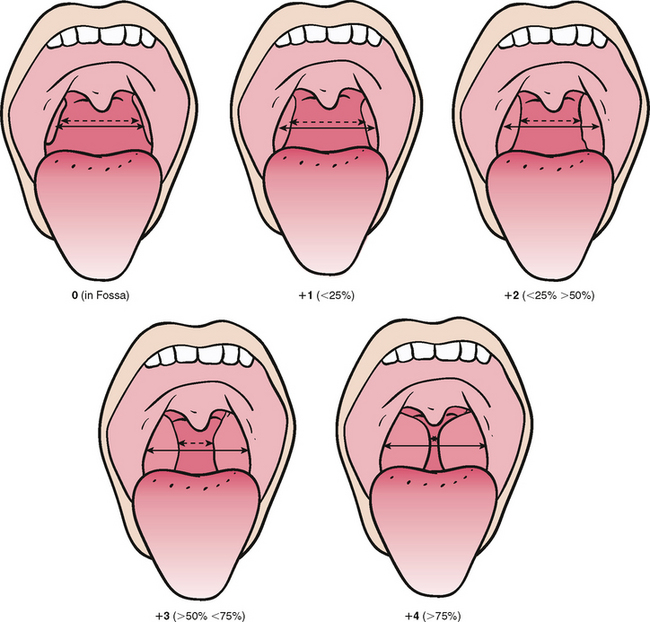

Airway management requires different consideration in the pediatric patient because of anatomic variations. The narrow nasal passages and glottis, combined with hypertrophic tonsils and adenoids, enlarged tongue, and greater secretions, produce a much greater risk of airway obstruction. The airway of all patients should be examined before sedation (Fig. 14-1). Patients with tonsillar tissue that occupies more than 50% of the pharyngeal space are at increased risk for respiratory obstruction, and alternative treatment options should be considered.3 Children demonstrate a reduced tolerance to respiratory obstruction. Thus sudden apnea is a greater concern in the pediatric age group. Because the thorax is smaller, with less expansion capability, children have less functional reserve. Consequently they are more prone to rapid desaturation on obstruction or respiratory depression. For this reason children with sleep apnea are not good candidates for sedation.

Cardiovascular parameters are different for children. The heart rate is faster and blood pressure is lower than in the adult. Children are more susceptible to bradycardia, decreased cardiac output, and hypotension. Unlike in the adult population, heart rate is the primary determinate of blood pressure in children. Compensatory mechanisms to maintain adequate blood pressure when the heart rate is depressed are not as well developed in children. Thus a decrease in heart rate leads to a corresponding decrease in blood pressure and tissue oxygenation. This concept must be well appreciated when giving drugs that depress the heart rate in the pediatric age population.

PATIENT SELECTION AND PREPARATION

INDICATIONS

Because sedation embodies a group of techniques designed to alter patient behavior, the practitioner should have a rationale for making the choice as to which patients will most likely benefit from their use. The indiscriminate application of these techniques to all patients must be avoided. Several behavioral or anxietyassessment profiles have been developed that can be of great help to the practitioner as the various techniques are introduced into a practice.4,5 As one gains experience, this decision becomes more one of clinical judgment and intuition as to which approach produces the most successful results for specific types of patients for that individual practitioner. No one technique or agent, or combination of agents, should be expected to be successful every time. There are also degrees of success, and total immobilization and near unconsciousness of a patient should not necessarily be equated with the most successful sedation. One should choose the agent and technique that best fits the patient type as well as the nature of what needs to be accomplished.

A thorough medical history is required to determine whether a patient is suitable for sedative procedures. This, along with a recent physical examination, constitute a risk assessment or physiologic status evaluation. This health evaluation should be used to place the patient in one of the categories set forth by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (http://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.htm) and should be documented in the record (Box 14-1).

Box 14-1 American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status Classification System

| Class I | A normal healthy patient |

| Class II | A patient with mild systemic disease (e.g., controlled reactive airway disease) |

| Class III | A patient with severe systemic disease (e.g., a child who is actively wheezing) |

| Class IV | A patient with severe systemic disease (e.g., a child with status asthmaticus) |

| Class V | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without operation (e.g., a patient with severe cardiomyopathy requiring heart transplantation) |

The medical history should include information regarding the following:

The physical evaluation should include the following:

INFORMED CONSENT

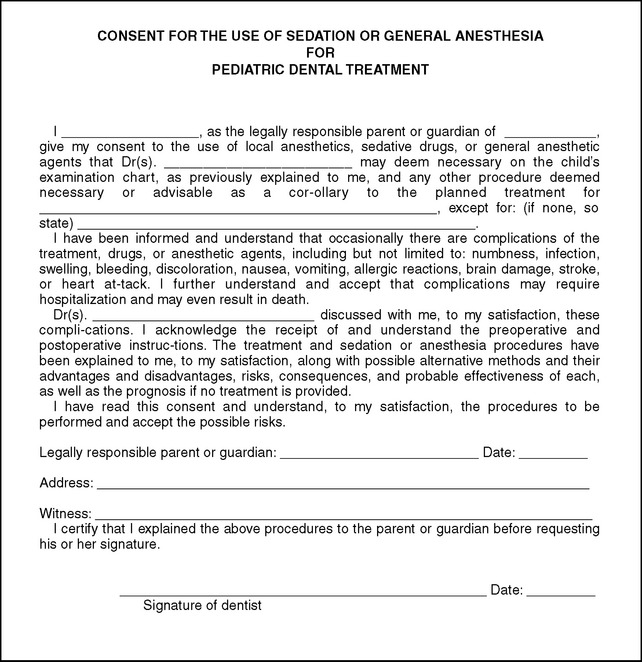

The parent or legal guardian must be agreeable to the use of sedation for the child. These individuals are entitled to receive complete information regarding the reasonably foreseeable risks and the benefits associated with the particular technique and agents being used, as well as any alternative methods available. Therefore the explanation should be in clear, concise terms that are familiar to them (Fig. 14-2). The consent form can be on or part of a sedation record with space provided for the signatures of all parties.

INSTRUCTIONS TO PARENTS

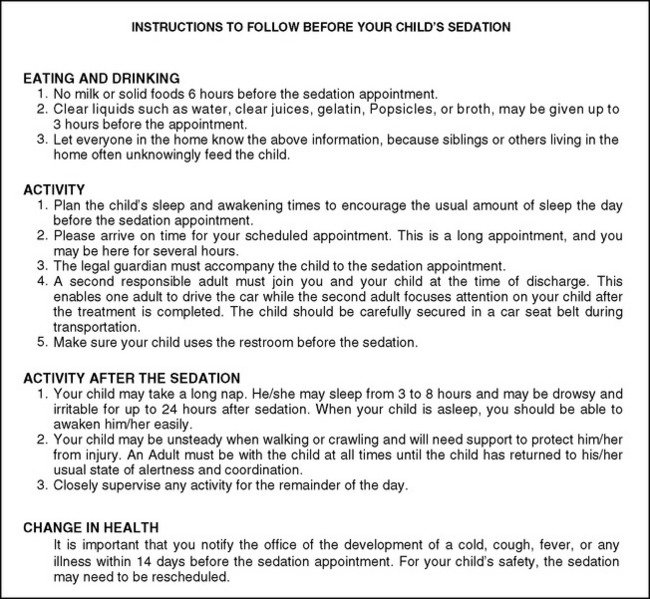

Information in written form should be reviewed with the person caring for the child and given to this person along with the notice of the scheduled appointment (Fig. 14-3). This information should include a 24-hour contact number for the practitioner.

Dietary instructions should be as follows (AAPD guidelines):

The reasons for these recommendations are twofold. First, emesis during or immediately after a sedative procedure is a potential complication that can result in aspiration of stomach contents leading to laryngospasm or severe airway obstruction. Aspiration may even present difficulties later in the form of aspiration pneumonia. At the very least, it creates an unfavorable disruption of the office routine. Second, because most sedative agents are administered by the oral route, drug uptake is maximized when the stomach is empty.

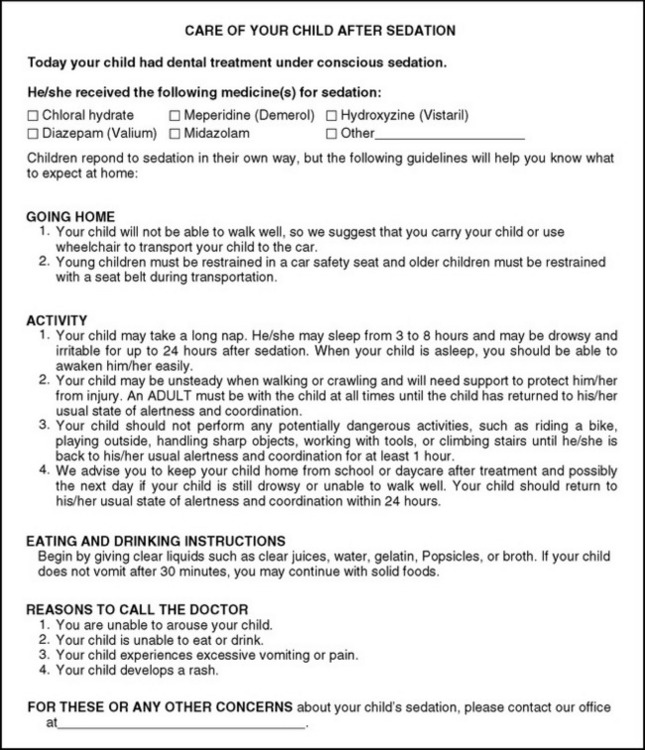

Knowledge on the part of the parent of what to expect is the most reliable way to ensure a calm, comfortable, and uncomplicated postsedation period. Therefore these instructions and recommendations should be in written form and should be reviewed again with the person responsible for the patient and given to this person at the time of discharge from the office (Fig. 14-4).

DOCUMENTATION

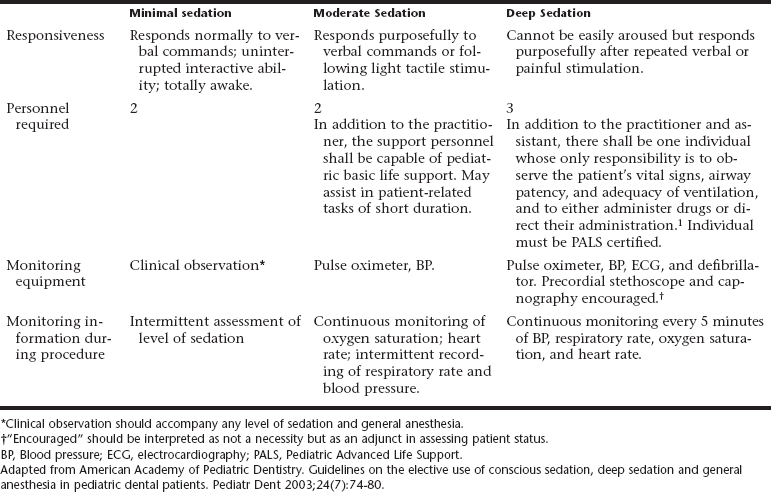

Intraoperatively the appropriate vital signs should be recorded as they are assessed (Table 14-2). Timed notations regarding the patient’s appearance should be included. The type of drug, the dose given, and the route, site, and time of administration should be clearly indicated. If a prescription is used, either a copy of the prescription or a note as to what was prescribed should also be a part of the permanent record.

Table 14-2 Template of Definitions and Characteristics for Levels of Sedation and General Anesthesia

After completion of treatment, the patient should be continuously observed in an appropriately equipped recovery area. The patient should remain under direct observation until respiratory and cardiovascular stability have been ensured. The patient should not be discharged until the presedation level of consciousness or a level as close as possible for that child has been achieved (Box 14-2). At the time of discharge, the condition of the patient should be noted.

SEDATION TECHNIQUES

Prescription medications intended to accomplish procedural sedation must not be administered without the benefit of direct supervision by trained personnel. It is no longer acceptable to administer any sedative drug outside of the treatment facility (e.g., given at home by the parent or caregiver). Administration of sedating medications at home poses an unacceptable risk, particularly for infants and preschool-aged children traveling in car-safety seats. (AAPD guidelines).

The primary goal of these techniques is to produce a quiescent patient to ensure the best quality of care. Another goal might be to accomplish a more complex or lengthy treatment plan in a shorter period by lengthening appointment times and thereby reducing the number of repeat visits required. Children presenting with a dental injury or acute pain may require sedation for completion of treatment as well as postoperative analgesia. In fact, the reduction in anxiety may reduce the amount of analgesia required. Sedation may also allow for more comfortable and acceptable treatment for physically impaired or cognitively disabled patients. Often these patients may benefit from parenteral sedation. Although the presence of a compromising medical condition is generally a contraindication to sedation, some patients in this category may in fact benefit from its use.6 This would, of course, include patients for whom stress reduction would reduce the likelihood of complications. These children should be managed in close cooperation with the physicians who regularly cares for them.

NITROUS OXIDE AND OXYGEN SEDATION

The objectives of nitrous oxide sedation include (AAPD guidelines):

Disadvantages of nitrous oxide–oxygen inhalation may include (AAPD guidelines):

Pharmacokinetics

A phenomenon termed diffusion hypoxia may occur as the sedation is reversed at the termination of the procedure. The nitrous oxide escapes into the alveoli with such rapidity that the oxygen present becomes diluted; thus the oxygen–carbon dioxide exchange is disrupted and a period of hypoxia is created. However, this phenomenon is reported not to occur in healthy pediatric patients.7 Nonetheless, to minimize this effect, the patient should be oxygenated for 3 to 5 minutes after a sedation procedure, if for no other reason than to allow for proper nasal hood evacuation of the exhaled gas.

Pharmacodynamics

Nitrous oxide reduces hypoxic-driven ventilation and has minimal effect on the hypercapnic respiratory drive. When used as a single agent, nitrous oxide will not cause hypoxemia. It should be avoided, however, in patients who rely significantly on hypoxia-driven ventilation, in whom exposure to high levels of oxygen can result in respiratory depression. When combined with other agents that depress respiration, nitrous oxide decreases the body’s normal response to low oxygen tension. These effects are usually negligible, however, because of the high concentration of oxygen administered with the combination. Nitrous oxide slightly increases the respiratory minute volume. As the patient becomes more relaxed from the effects of nitrous oxide, the respiratory rate may decrease slightly. The gas is nonirritating to the respiratory tract and can be given to patients with asthma without fear of bronchospasm. Problems can arise, however, from the added respiratory effects when it is given in combination with narcotics or other CNS depressants.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses