Chapter 13

Oral Mucosal Lesions

Miriam R. Robbins

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Radiology, and Medicine, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY, USA

Introduction

The intent of this chapter is to identify some of the most common oral lesions in the older adult and present the information in an easily accessible format. Clinical photos are presented with each condition to facilitate identification and diagnosis.

The oral mucosa is a common site for a wide variety of lesions, including ulcerative, vesiculobullous, desquamative, lichenoid, infectious, and malignant. Both normal changes associated with aging and pathologic factors can contribute to the presence of oral pathoses. As people age, the mucosa becomes atrophic resulting in thinner and less elastic tissue. This change in cellular structure combined with a decline in the immunologic responsiveness also associated with aging, results in an increased susceptibility to infection and trauma. Other contributing factors are the increases in incidence of systemic diseases and the use of multiple medications, especially those that result in xerostomia (discussed in Chapter 14).

Any mucosal lesion that does not respond as expected within an appropriate period of time or that persists despite all attempts to resolve any underlying etiology should be biopsied to determine the diagnosis. All patients, even if edentulous, should have an annual head and neck exam with a through intraoral soft tissue examination to evaluate the presence of any lesions and to intervene at an early stage with appropriate treatment.

Each of the conditions presented will be discussed according to the following format:

- Etiology

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Treatment.

Burning mouth syndrome

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is characterized by a continuous burning sensation of the oral mucosa and/or tongue, usually without accompanying clinical and laboratory findings (Patton et al., 2007). It is more common in middle-aged or older women with increasing prevalence associated with increasing age (Bergdahl & Bergdahl, 1999), and is often accompanied by subjective complaints of dysgeusia and xerostomia.

Etiology

The most common etiology of BMS is idiopathic, although it may represent a chronic neuropathic condition that may be exacerbated by psychogenic factors. Other conditions including lichen planus, candidiasis, menopause and other hormone imbalances, nutritional or vitamin deficiencies, xerostomia, gastrointestinal disorders, diabetes, thyroid disorders, nerve injuries, or medication side effects may need to be considered (Patton et al., 2007).

Clinical presentation

BMS is characterized by the absence of clinical signs. Candidiasis and salivary hypofunction may be concurrent findings.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is established after all possible etiologic factors have been eliminated based on history, physical evaluation and laboratory studies. Baseline complete blood count (CBC) with differential, fasting glucose, vitamin B12, folic acid, iron, ferritin, and thyroid levels should be obtained.

Treatment

There is no definitive cure. Patients should be reassured that this is not an infectious or malignant condition, but should be counseled that this is a chronic pain condition. Approximately 50% of patients with BMS show improvement of symptoms after 6–7 years (Sardella et al., 2006). Treatment is aimed at relieving discomfort and should be individualized based on symptoms. A variety of topical and systemic treatments have been proposed with variable evidence to support their use (Patton et al., 2007). There is some evidence to support cognitive behavioral therapy as an adjunct to pharmacologic therapies (Sardella et al., 2006).

Topical treatments include clonazepam-dissolvable wafers (0.5 mg twice daily) or mouth rinse (1 mg/5 ml), oral capsaicin, doxepin solution (10 mg/ml), viscous lidocaine, and diphenhydramine elixir (12.5 mg/5 ml).

Systemic treatments include alpha-lipoic acid (600 mg daily), low doses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, clonazepam (0.5 mg tablets 3 times a day) or alprazolam (0.25 mg tablets 3 times a day). Dosages need to be adjusted according to the individual response and the presence/severity of side effects. Older patients taking central nervous system depressants should not be prescribed these medications without consultation with the patient’s physician. In fact, systemic treatments may best be managed the patient’s physician or by an appropriate dental specialist due to the prolonged nature and potential side effects (including addiction/dependency) of these therapies.

Candidiasis (see also Chapter 2)

Etiology

Oral candidiasis is an opportunistic infection most commonly caused by Candida albicans overgrowth, although there are other Candida species that can also cause this condition. In adults, oral yeast infections become more common with increased age, especially among denture wearers (Darwazeh et al., 1990). Other risk factors include antibiotic therapy, xerostomia, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, corticosteroids (both systemic and inhaled), and poor oral hygiene (Peterson, 1992).

Clinical presentation

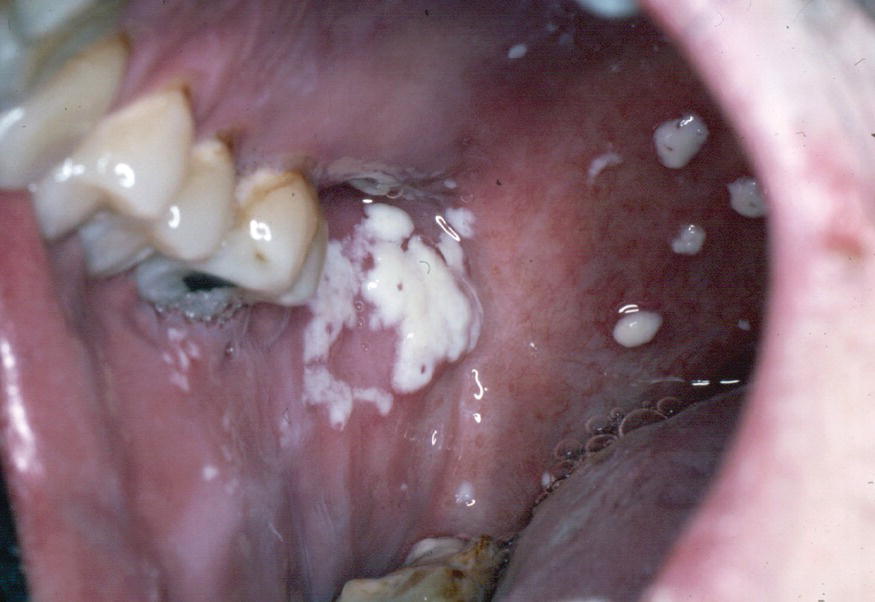

Pseudomembraneous candidiasis (Fig. 13.1)

- Most common form.

- Soft-white elevated plaques present on mucosal membranes.

- Easily wiped away, leaving an erythematous base.

- Anywhere in mouth, but hard palate, tongue, and buccal mucosa common sites.

- May extend into oropharynx.

Figure 13.1 Pseudomembranous candidiasis.

Erythematous (atrophic) candidiasis (Fig. 13.2)

Figure 13.2 Erythematous candidiasis.

- Erythematous sensitive patches that look “raw.”

- Several forms characterized by cause and location:

- Acute atrophic (antibiotic sore mouth):

- Commonly caused by broad spectrum antibiotics.

- Atrophic dorsal surface of tongue.

- Complaint of burning sensation.

- Chronic atrophic (denture stomatitis) (Fig. 13.3):

- Commonly seen in patients who wear poorly fitting removable prostheses for extended periods of time (i.e., do not remove at night).

- Well-demarcated erythematous mucosa present under denture base (usually maxilla).

- Patients usually asymptomatic.

- Angular chelitis (Fig. 13.4):

- Erythema and fissuring of commissures of lips (usually bilaterally).

- Often caused by a combination of fungal and bacteria infection.

- Median rhomboid glossitis (central papillary atrophy) (Fig. 13.5):

- Well-demarcated rhomboid area seen in the midline of the tongue anterior to the circumvallate papillae.

- “Kissing” lesion frequently seen on hard palate.

- Acute atrophic (antibiotic sore mouth):

Figure 13.3 Denture stomatitis.

Figure 13.4 Angular chelitis.

Figure 13.5 Median rhomboid glossitis.

Hyperplastic candidiasis (candida leukoplakia) (Fig. 13.6)

Figure 13.6 Hyperplastic candidiasis.

- Well-defined confluent white patches that can not be wiped off.

- Common on buccal mucosa near commissures, but can be seen on hard palate and lateral tongue.

- May be leukoplakia that is colonized by Candida.

- Biopsy is warranted if no resolution following antifungal treatment or if there are focal areas of erythema associated with white patches.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of oral candidiasis is often made based on the clinical signs and symptoms and is treated empirically with antifungal medications. Additional adjunctive methods for the diagnosis of oral candidiasis include exfoliative cytology, biopsy, and culture.

Treatment

Oral candidiasis may be treated with topical or systemic antifungal therapy (Tables 13.1 & 13.2). Chronic candidiasis often requires a prolonged period of therapy. Topical applications of various forms of antifungal medications are commonly used to treat acute cases. Rinses tend to be less effective than other topical forms because the duration of tissue contact is suboptimal. Topical troches/pastilles prolong the contact of the medication with oral mucosa and are generally safe to use because of poor systemic absorption. They may not be appropriate for patients with xerostomia due to decreased ability to dissolve this form. These forms are often high in sugar and need to be used with care in diabetic patients. Oral hygiene should be emphasized to decrease the development of caries. Patients who wear dentures should be instructed to remove them prior to using a rinse, troche, or pastille (Giannin et al., 2011).

Table 13.1 Topical antifungal agents

| Agents | Dose/unit | Daily dosage |

| Nystatin topical cream, powder, ointment | 100 000 U/g | Apply thin layer to affected area 3 times daily (can be applied to inner surface of denture as well) |

| Nystatin oral suspension | 100 000 U/ml | 400 000–600 000 U po; swish and swallow 4–5 times a day |

| Nystatin pastilles | 200 000 U | 200 000–400 000 U po 4–5 times a day |

| Nystatin vaginal suppositories (OTC) | 100 000 U | 100 000 U po, dissolve in mouth 4 times a day |

| Clotrimazole troche | 10 mg | 10 mg dissolved po 5 times a day for 2 weeks |

| Clortrimazole vaginal cream (OTC) | 1% | Apply thin layer to tissue side of denture and/or affected area of mouth 4 times a day |

| Miconazole nitrate vaginal cream (OTC) | 2% | Apply thin layer to tissue side of denture and/or affected area of mouth 4 times a day |

| Miconazole vaginal suppository | 100 or 200 mg | Dissolve one suppository in mouth 4 times a day |

| Miconazole (Oravig®) buccal tablet |

50 mg | Place one tab on buccal mucosa in morning for 14 days. Allow to dissolve, do not chew |

| Ketoconazole cream | 2% | Apply thin layer to tissue side of denture and/or affected area of mouth 4 times a day |

| Amphotericin B suspension | 100 mg/ml | 100–200 mg po; swish and swallow 4 times a day |

| Nystatin–tramcinolone acetonide ointment | 15 g tube | Apply to corners of mouth after meals and at bedtime for 2 weeks |

OTC, over the counter; po, by mouth.

Table 13.2 Systemic antifungal agents

| Agents | Form | Dosage |

| Fluconazole (Diflucan®) | Capsules | 100 mg qd |

| Ketoconazole (Nizoral®) | Tablets | 200 or 400 mg qd |

| Miconazole (Daktarin®) | Tablets | 50 mg qd |

| Itraconazole (Sporanox®) | Capsules | 100 mg qd |

qd, once a day.

Azole antifungals (the most common type of systemic medications) are potent inhibitors of cytochrome P450 system and therefore have many drug–drug interactions with other commonly prescribed medications (e.g., statins, tricyclic antidepressants, oral hypoglycemic, and warfarin) (Gubbin & Heldenbrand, 2010). Prolonged use can also lead to hepatotoxicity and liver function tests should be performed if the medication is used for more than 3 weeks.

All medications, whether topical or systemic, should be continued for several days after resolution of clinical signs. Recurrence is common while underlying etiologic factors exist. For patients with denture stomatitis, a topical antifungal can be applied to the mucosa and denture base prior to insertion (Webb et al., 2005). Additionally, all removable prostheses must also be treated with antifungals to prevent a potential source of reinfection. Patients should be advised to remove and clean dentures every night. Following brushing the dentures, they can be soaked in a dilute bleach solution (1 part bleach to 10 parts water) tissue side down for 10 minutes. Angular chelitis generally respond well to combination therapy containing both an antifungal and steroid.

Epulis fissuratum (inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia, denture-induced fibrous hyperplasia, denture granuloma)

Epulis is a nonspecific term used for tumor-like masses of the gingiva. Epulis fissuratum occurs as a result of trauma from an ill-fitting or over-extended denture. It appears to occur more frequently in women (Zhang et al., 2007).

Etiology

As alveolar bone resorbs, the denture flange become overextended and traumatizes the sulcular tissue resulting in an overgrowth of fibrous connective tissue.

Clinical presentation

Epulis presents as a single or multiple folds of hyperplastic granulation tissue surrounding the denture flange, usually in the anterior maxillary and mandibular vestibule. The tissue can become ulcerated and painful.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on clinical appearance and presence of removable prostheses. Any ulcerated area that does not heal once the etiology has been resolved should be biopsied to rule out squamous cell carcinoma.

Treatment

Surgical resection of tissue is usually necessary followed by fabrication of new prostheses with reduced flange.

Geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis)

This is a relatively common chronic condition that is usually asymptomatic.

Etiology

It is suggested, but not confirmed, that this condition may be related to psoriasis or to a hypersensitivity reaction. Some patients report exacerbation during times of stress, eating certain foods, or using certain oral hygiene products.

Clinical appearance

The dorsum of the tongue is the most common site; however, it can be found on the buccal mucosa or lip (erythema migrans). It is characterized by a migrating pattern of irregul/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses