Facial Cosmetic Surgery

• Botulinum Toxin A (Botox) Injection for Facial Rejuvenation

• Cervicofacial Rhytidectomy (Facelift)

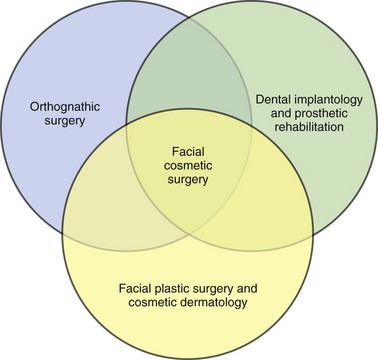

Facial cosmetic surgery in this section refers to soft tissue procedures of the face. In reality, modern facial cosmetic surgery includes procedures that enhance the appearance of the skeleton (orthognathic surgery), esthetic dental implantology and prosthetic rehabilitation, dermatologic procedures (skin resurfacing), hair restoration, and facial plastic surgery (Figure 13-1). Only oral and maxillofacial surgeons have the opportunity to provide all these services.

Figure 13-1 The full scope of facial cosmetic surgery encompasses three disciplines: orthognathic surgery, dental implantology/prosthetics, and facial plastic surgery with cosmetic dermatology. (From Bagheri S, Bell B, Khan HA: Current therapy in oral and maxillofacial surgery, St. Louis, 2012, Saunders.)

Botulinum Toxin A (Botox) Injection for Facial Rejuvenation

Examination

Several prominent horizontal forehead wrinkles (due to frontalis muscle action) are present at rest (Figure 13-2, A) and are accentuated with animation (Figure 13-2, B). Multiple hyperdynamic rhytids (lines on the face) are seen lateral to the eye and are most pronounced on animation (orbicularis oculi region, also known as “crow’s feet”; Figure 13-3, C). At rest, fine vertical glabellar furrows are present, and upon animation and frowning, the glabella muscle bulge becomes significantly prominent (the corrugator muscle is responsible for the vertical glabellar furrows, and the procerus muscle is responsible for the horizontal glabellar furrows). A glabellar spread test reveals that the glabellar lines are substantially decreased when physically manipulated or spread apart. (This is a good indication that the muscle and its overlying soft tissue are the etiology of the lines. During the physical exam, it is important to distinguish between dynamic and static wrinkles. Botox decreases dynamic wrinkles because of its effect on muscles. Static wrinkles may be treated using soft tissue fillers to decrease skin laxity at rest.)

Figure 13-2 A, Forehead wrinkles secondary to frontalis muscle functioning. B, Forehead lines accentuated during frontalis function. C, Hyperdynamic periorbital lines (crow’s feet) accentuated with animation.

Figure 13-3 A, One month postoperative view at rest, showing significant reduction of horizontal forehead lines. B, One month postoperative view upon brow elevation, showing significant reduction of horizontal forehead lines with animation. C, One month postoperative view of the lateral periorbital lines (crow’s feet) seen during animation.

Treatment

After a complete discussion of the procedure, risks, and alternatives, the patient signed the informed consent (which addressed all the complications listed later). One hundred units of Botulinum Toxin A was reconstituted with 3.3 ml of unpreserved normal saline. (According to a study by Alam and colleagues in 2002, the use of preservative-containing normal saline is less painful than preservative-free saline. However, this is not in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations.) Botox is available in a sealed vacuum container that allows for easy reconstitution with saline. The resulting solution provides 3 units per 0.1 ml, or 15 units per 0.5 ml. Botox should be reconstituted gently (shaking and trauma to the toxin can diminish its potency) with a 21-gauge needle and then gently drawn into a tuberculin syringe. The syringe can be used with a short 30-gauge needle.

Ice was allowed to rest on the injection sites for as long as the patient tolerated. The patient was instructed to remain upright for at least 4 hours and was allowed to apply makeup 4 hours after injection (to minimize manipulation and thus diffusion of the toxin). She was allowed to resume exercise the next day. She was instructed to expect a noticeable effect in 3 to 4 days, with maximum benefit in 30 days (Figure 13-3). Follow-up was scheduled in 1 week. The areas can be reinjected after a minimum of 3 months has elapsed (earlier injections can increase the chance of antibodies developing).

Complications

• Undesired effect (can be related to the patient’s expectations or rate of metabolism, dosing, anatomic variations, or inadequate site of injection).

• Short duration of the desired effect.

• Postinjection bruising: This is most common in the periorbital region and can be minimized by avoiding aspirin or NSAIDs for 7 to 14 days prior to injection.

• Blepharoptosis: The reported occurrence is 1% to 2% of periorbital injections. This can be treated with an α2-adrenergic agonist (apraclonidine 0.5% eye drops, to be used 30 minutes before social situations), which stimulates Mueller’s muscle, resulting in hours of transient lid opening.

• Transient headaches, pain, edema, and erythema at the injection site.

• Formation of neutralizing antibodies: This has been reported to occur with repeat injections within 1 month of the previous injections; it also was reported with doses greater than 100 units per treatment session. This has not been reported for the cosmetic use of Botox; however, it is recommended that a period of at least 3 months elapse between injections.

Alam, M, Dover, JS, Arndt, KA. Pain associated with injection of botulinum A exotoxin reconstituted using isotonic sodium chloride with and without preservative: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 2002; 138(4):510–514.

Carruthers, J, Carruthers, A. A prospective, randomized, parallel group study analyzing the effect of BTX-A (Botox) and nonanimal sourced hyaluronic acid (NASHA, Restylane) in combination compared with NASHA (Restylane) alone in severe glabellar rhytides in adult female subjects: treatment of severe glabellar rhytides with a hyaluronic acid derivative compared with the derivative and BTX-A. Dermatol Surg. 2003; 29:802–809.

Connor, MS, Karlis, V, Ghali, GE. Management of the aging forehead: a review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003; 95(6):642–648.

Frampton, J, Easthope, S. Botulinum toxin A (Botox Cosmetic): a review of its use in the treatment of glabellar frown lines. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003; 4(10):709–725.

Freund, B, Schwarz, M, Symington, JM. Botulinum toxin: new treatment for temporomandibular disorders. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000; 38:466–471.

Henriques Castro, W, Santiago Gomez, R, da Silva Oliveira, J, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in the management of masseter muscle hypertrophy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005; 63(1):20–24.

Hexsel, DM, De Almeida, AT, Rutowitsch, M, et al. Multicenter, double-blind study of the efficacy of injections with botulinum toxin type A reconstituted up to six consecutive weeks before application. Dermatol Surg. 2003; 29(5):523–529.

Kane, M. Botox injections for lower facial rejuvenation. Oral Maxillofac Surgery Clin North Am. 2005; 17(1):41–49.

Lorenc, ZP, Kenkel, JM, Fagien, S, et al. A review of onabotulinumtoxin A (Botox). Aesthet Surg J. 2013; 33(1 Suppl):9S–12S.

Niamtu, J, III. Botulinum toxin A: a review of 1,085 oral and maxillofacial patient treatments. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 61(3):317–324.

Rohrich, R, Janis, J. Botox for the treatment of dynamic and hyperkinetic facial lines and furrows: adjunctive use in facial aesthetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 112(5 Suppl):53S–54S.

Solish, N, Benohanian, A, Kowalski, JW. Canadian Dermatology Study Group on Health-Related Quality of Life in Primary Axillary Hyperhidrosis: prospective open-label study of botulinum toxin type A in patients with axillary hyperhidrosis—effects on functional impairment and quality of life. Dermatol Surg. 2005; 31(4):405–413.

Trindade De Almeida, AR, Kadunc, BV, Di Chiacchio, N, et al. Foam during reconstitution does not affect the potency of botulinum toxin type A. Dermatol Surg. 2003; 29(5):530–531.

Vartanian, AJ, Dayan, SH. Facial rejuvenation using botulinum toxin A: review and updates. Facial Plast Surg. 2004; 20(1):11–19.

Lip Augmentation

Examination

Lips. The lips are symmetrical (Figure 13-4). The upper lip to lower lip height ratio is about 1 : 2 (in general, an aesthetic upper lip is one third of the total lip mass, and the lower lip represents two thirds of the total lip height). The upper lip is relatively deficient in volume compared with the lower lip. Cupid’s bow and the vermillion border are well defined, with good profile projection. Four millimeters of central incisors is visible at rest (normal range is 3 to 4 mm for females and 2 to 3 mm for males), with no gingival show on smiling (no “gummy” smile). She does not exhibit lip incompetence. The nasolabial angle is within normal limits (100 degrees ± 10 degrees).

Labs

Lab tests are not indicated unless there is a known history of coagulopathies (increased risk of hematoma, bruising, and erythema at the injection site). Unlike collagen, hyaluronic acid is identical among species, making it highly biocompatible and thus eliminating the need for allergy testing (see Complications).

Treatment

Bilateral infraorbital nerve blocks are given to achieve upper lip anesthesia without local infiltration in the areas to be augmented to avoid temporary tissue distortion secondary to the injection. The white roll is augmented on the upper lip, starting at the midline and following the contour of Cupid’s bow to enhance both definition and projection. The material is injected in a linear threading fashion as the needle is withdrawn away from the midline via two or three injection sites. The upper lips are intermittently massaged to achieve uniform distribution of the filler. The contralateral side is injected in a similar fashion. The body of the lip is also injected in a similar fashion to achieve volume enhancement of the lips. For the current patient, a total of one syringe was used for the upper lip (Figure 13-5).

Complications

Several formulations for hyaluronic acid are available for injection into soft tissue, but not all are FDA approved. Olenius conducted the first clinical study to evaluate biodegradable implants. He evaluated 113 subjects after injection with partially cross-linked hyaluronic acid and reported no allergic reactions and infrequent side effects; these were limited to localized erythema and swelling related to superficial placement of the material, small hematoma formation, and lumpiness secondary to uneven injection. In 2001, Lowe and associates studied 709 patients injected with hyaluronic acid preparations. They reported a 0.42% incidence of delayed inflammatory skin reactions that started about 8 weeks postinjection. A review of worldwide data on 144,000 patients treated in 1999 indicated that the major reaction to injectable hyaluronic acid was localized hypersensitivity, occurring in approximately 1 of every 1,400 patients treated. This study concluded that hypersensitivity to non-animal-source hyaluronic acid gel is the major adverse event and is most likely secondary to impurities of bacterial fermentation. More recent data indicate that the incidence of hypersensitivity appears to be declining after the introduction of a more purified hyaluronic acid raw material.

Danesh-Meyer, HV, Savino, PJ, Sergott, RC. Case reports and small case series: ocular and cerebral ischemia following facial injection of autologous fat. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119(5):777–778.

Douglas, RS, Donsoff, I, Cook, T, et al. Collagen fillers in facial aesthetic surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2004; 20(2):117–123.

Duranti, F, Salti, G, Bovani, B, et al. Injectable hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation: a clinical and histological study. Dermatol Surg. 1998; 24(12):1317–1325.

Fagien, S. Facial soft-tissue augmentation with injectable autologous and allogeneic human tissue collagen matrix (Autologen and Dermalogen). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105(1):362–373.

Friedman, PM, Mafong, EA, Kauvar, AN, et al. Safety data of injectable nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2002; 28(6):491–494.

Lowe, NJ, Maxwell, CA, Lowe, P, et al. Hyaluronic acid skin fillers: adverse reactions and skin testing. Am Acad Dermatol. 2001; 45(6):930–933.

Niamtu, J. New lip and wrinkle fillers. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005; 17(1):17–28.

Olenius, M. The first clinical study using a new biodegradable implant for the treatment of lips, wrinkles, and folds. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998; 22(2):97–101.

Schanz, S, Schippert, W, Ulmer, A, et al. Arterial embolization caused by injection of hyaluronic acid (Restylane). Br J Dermatol. 2002; 146(5):928–929.

Rhinoplasty

Examination

Examination of the Nose

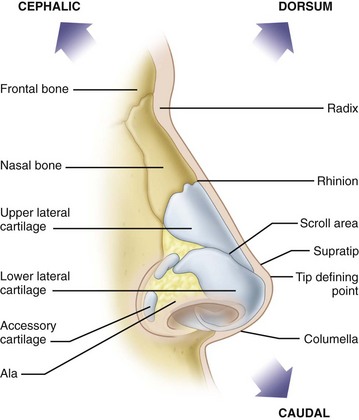

Skin. The skin meets the criteria of Fitzpatrick type II with no evidence of acne or excessive sebaceous secretions. The skin and soft tissue envelope have adequate thickness over the dorsum and tip (Figure 13-6).

Dorsum. There is a prominent dorsal hump on the profile view (Figure 13-7). The mid dorsum is rectangular in shape on the frontal view. The nasal dorsum is wide but symmetrical.

The different anatomic regions of the nose and their main characteristics for cosmetic and functional rhinoplasty are shown in Table 13-1.

Table 13-1

Anatomic Regions of the Nose and Their Main Characteristics for Cosmetic and Functional Rhinoplasty

| Anatomic Region | Main Characteristics |

| Radix | Location, size |

| Dorsum | Width, size, symmetry |

| Tip | Volume, projection, shape, definition, rotation, width |

| Nasal base | Alar base shape, nostril size, columellar anatomy, alar width, symmetry |

| Septum | Deviation, perforation |

| Turbinates | Size, obstruction of airflow, inflammation |

From Bagheri SC, Bell RB, Khan HA (eds): Current therapy in oral and maxillofacial surgery, St Louis, 2012, Saunders.

Treatment

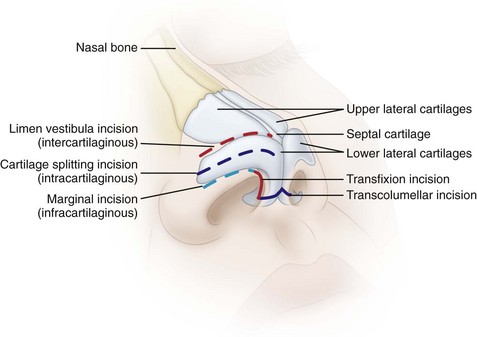

The surgical approach (endonasal versus open rhinoplasty) depends on the complexity of the case and the experience and preference of the surgeon. Incisions for endonasal rhinoplasty include the following (Figure 13-8):

• Intercartilaginous or limen vestibula incision (between the upper and lower lateral cartilages)

• Intracartilaginous or cartilage-splitting incision (through the upper aspect of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilage)

• Infracartilaginous or marginal incision (on the inferior aspect of the lower lateral cartilage)

Standard incisions for approaching the nasal septum include the transfixion incision (through the membranous septum) and the Killian incision (incision over the cartilaginous septum). Most simple rhinoplasties can be done via an endonasal approach. However, if complex tip work or spreader grafts are required, an open transcollumellar incision allows greater access and visibility than the cartilage delivery approach (Figure 13-9). The scar from this incision is usually not visible several months after the procedure.

Figure 13-9 Exposure of nose with an open rhinoplasty incision. (From Bagheri SC, Bell RB, Khan HA (eds): Current therapy in oral and maxillofacial surgery, St Louis, 2012, Saunders.)

Open Septorhinoplasty

1. Septoplasty and harvest of septal cartilage

2. Submucous resection and turbinate outfracture

3. Transcolumellar incision for access to the dorsum, septum, and nasal valve

4. Reduction of the nasal dorsum (rasp or osteotome reduction)

5. Nasal tip refinement (resection and/or suture techniques can be used, based on the surgeon’s preference)

6. Bilateral spreader grafts (from septum) for opening of the nasal valves

7. Bilateral low to high nasal osteotomies for narrowing of the dorsum and closure of the “open book” deformity

Under general anesthesia, lidocaine with epinephrine was injected along the nasal septum, columella, dorsum, and nostril areas, and adequate time was given for vasoconstriction (some surgeons limit the amount of subcutaneous local anesthetic injected to minimize tissue distortion, for improved intraoperative assessment). A septoplasty and septal cartilage harvest were performed via a left hemitransfixion incision (a minimum 1-cm strut of dorsal and caudal cartilage should be left intact for adequate support), followed by submucosal resection with lateral displacement of the right inferior turbinate. Careful attention was given to maintaining adequate dorsal and columellar cartilage, to avoid a saddle nose deformity. An open rhinoplasty (inverted V transcolumellar with infracartilaginous incisions) was performed, with subsequent resection of 4 mm of the cephalic margin of the lower lateral cartilages (cephalic trim or volumetric reduction). Domal equalization and creation sutures were used to provide tip definition (some surgeons may elect to split the domes). Reduction of the bony dorsum was performed using a rasp, followed by excision of the cartilaginous dorsum using fine scissors. Strut and shield grafts were not used in this patient (although some authors suggest that strut and shield grafts be used in most patients). The nasal tip was supported by suturing the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages to the nasal septum (a columellar strut can be used to achieve greater tip projection). The septum was disarticulated from the upper lateral cartilages bilaterally, and a spreader graft was placed (to increase the internal nasal valve). Finally, low-to-high lateral nasal osteotomies were performed, and the nasal complex was fractured in to close the open “book deformity” and address the width of the dorsum. Figure 13-10 shows the postoperative patient profile.

Bagheri, SC. Primary cosmetic rhinoplasty. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012; 24(1):39–48.

Bagheri, SC, Khan, HA, Cuzalina, A. Rhinoplasty; current therapy. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012; 24(1):ix–x.

Bagheri, SC, Khan, HA, Jahangirian, A, et al. An analysis of 101 primary cosmetic rhinoplasties. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 70(4):902–909.

Beekhuis, GH. Nasal obstruction after rhinoplasty: etiology and techniques for correction. Laryngoscope. 1976; 86:540.

Bohlouli, B, Bagheri, SC. Revision rhinoplasty. In: Bagheri SC, Bell RB, Khan HA, eds. Current therapy in oral and maxillofacial surgery. St Louis: Saunders; 2012:901–910.

Daniel, RK. Rhinoplasty: an atlas of surgical techniques. New York: Springer; 2002.

Gunter, JP. The merits of the open approach in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997; 99(3):863–867.

Johnson, CM, Toriumi, DM. Open structure rhinoplasty. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990.

Kamer, FN, McQuown, SA. Revision rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988; 114:257.

Maniglia, AJ. Fatal and major complications secondary to nasal and sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1989; 99:276.

Teichgraeber, JF, Riley, WB, Parks, DH. Nasal surgery complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 85:527.

Teichgraeber, JF, Russo, RC. Treatment of nasal surgery complications. Ann Plast Surg. 1993; 30:80.

Nasal Septoplasty

Examination

The nose is examined in conjunction with the other facial structures for both its functional and cosmetic aspects (see the section Rhinoplasty in this chapter). Physical examination should include inspection and direct visualization of the septum, turbinates, nasal mucosa, nasal passages, nasal valve, radix, dorsum, columella and anterior nasal spine. (Occasionally a tumor occurs in the nasal passages, and an area showing changes suspicious for neoplasia should be biopsied.) The examination of the current patient proceeded as follows.

Imaging

In the current patient, axial and coronal CBCT imaging demonstrated significant leftward deviation of the septum with reduced air space and compensatory enlargement of the right inferior turbinate (Figure 13-11, A and B). The panoramic radiograph obtained for third molar evaluation in this patient, shows impaction of the mandibular third molars, and also demonstrates the deviated septum (Figure 13-11, C).

Treatment

In the current patient, general anesthesia was induced and an oral endotracheal tube was placed for airway maintenance and administration of oxygen and anesthetic agents. Two main incisions are used to approach the septum, the Killian incision and the hemitransfixion incision (Figure 13-12). The Killian incision is the most common and is used to approach the septum without direct access to the caudal segment. It is the best in/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses