Chapter 12

Temporomandibular joint

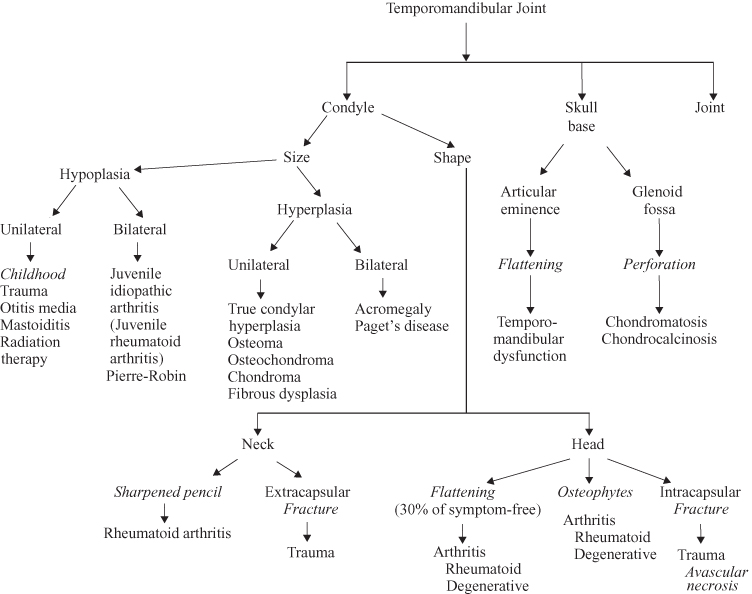

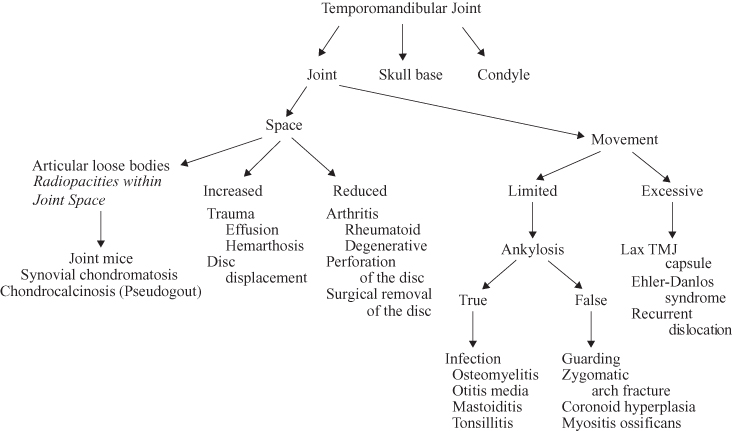

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) has three basic components, the condylar head (Figure 12.1), joint space, (Figure 12.2), and glenoid fossa and articular eminence of the temporal bone (Figure 12.1). On conventional radiography, including panoramic radiography, conventional tomography, bone window helical computed tomography (HCT) (Figure 12.3a), and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) the joint space is visualized as a radiolucent structure by virtue of its wholly soft-tissue content. The only radiopacities that may be observed occasionally within this space by the aforementioned modalities are articular loose bodies (Figure 12.2). These radiopacities range from innocent joint mice (isolated bone fragments from the condyle or temporal bone), synovial chondromatosis,1 and pseudogout (chondrocalcinosis).2 The last two diseases can erode through the skull base. Yokota et al. had included chondrosarcoma and osteosarcoma in the differential diagnosis of a case of synovial chondromatosis.3

Figure 12.1. Temporomandibular joint—condyle and skull base.

Figure 12.2. Temporomandibular joint—joint.

Figure 12.3. The bone window computed tomograph (a) and magnetic resonance images (T1-weighted (b), and fat-saturated T2-weighted (c) are of the same patient investigated for a painful joint after trauma). (a) This displays exquisite bone detail. The soft tissue in this bone window is a uniform gray, punctuated only by the air-filled external acoustic meatus. (b) The hypointensity of the cortices of the condyle and glenoid fossa is similar to that of the air-filled external acoustic meatus. The T1-weighted MR image displays the soft-tissue anatomy in great detail. The isointense (grey) muscle fasiculae of the lateral pterygoid muscle are clearly obvious inserting into the pterygoid fossa. The interarticular disc appears as a hypointense (dark) structure in a normal relationship to the condylar head. (c) The hyperintense (bright white) area represents an effusion into the joint space and is indicative of ongoing inflammation. The hyperintense condylar marrow, which appeared relatively hyperintense in (b) is now hypointense in the fat-saturated (fat-suppression) T2-weighted image.

Reprinted with permission from MacDonald-Jankowski DS, Li TK, Matthew I. Magnetic resonance imaging for oral and maxillofacial Surgeons. Part 2: Clinical applications. Asian Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 2006;18:236–247.

The anatomical components and disease characteristics of the soft tissue of the joint space are displayed by soft-tissue window HCT and especially by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (see Figure 12.3b, c). Pereira et al. pioneered an inconclusive study using ultrasound.4

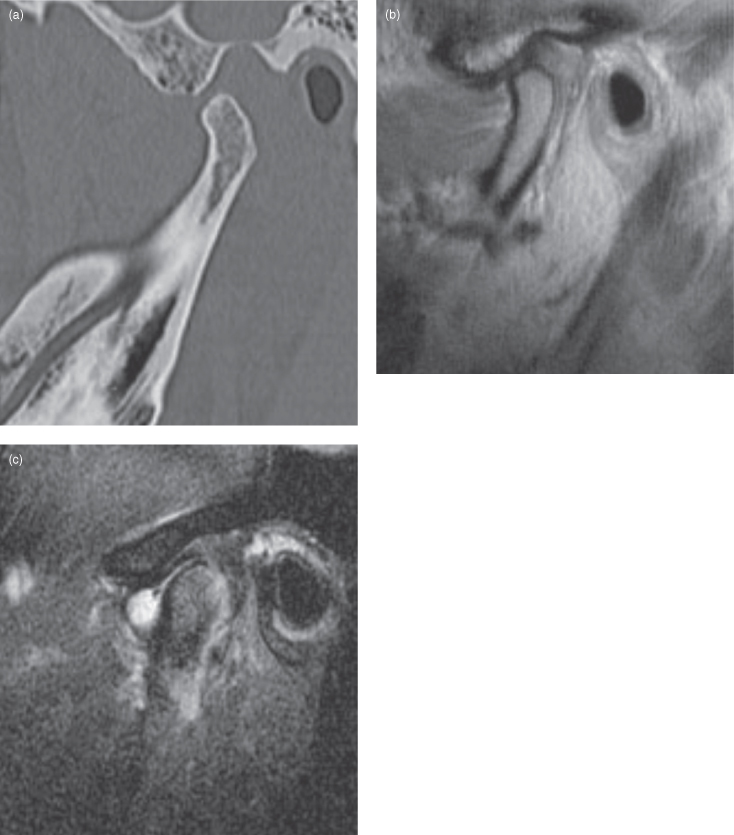

The first image usually taken of a patient presenting with symptoms or signs indicating a TMJ problem is the panoramic radiograph. This provides the clinician with a lateral view of the condylar head and neck. Although the width of the focal plane of the panoramic radiograph is likely to include the whole width of the condylar head, the shape of the head can vary between patients. Nevertheless, if the condyles are symmetrical in shape and size, it is reasonable to assume they are normal, particularly in the absence of symptoms. The significance of flattened condyles, erosions, and osteophytes (Figure 12.4) are considered later.

Figure 12.4. These T1-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRI) display the side displaying partial disc displacement displayed normal disc position in the open mouth position (a) and anterior disc displacement in the closed mouth position (b), whereas the side displaying complete disc displacement displayed anterior disc displacement both in the open (c) and closed(d) mouth positions. The marrow of the condyle is normally fat-filled and is hyperintense on T1-weighted MRI. The abnormal side exhibits an osteophyte, which gives the abnormal condyle the appearance of a bird’s head. The normal side displays the meniscus (hypointense disc) properly interposed between the condyle and articular surface in both open and closed positions. The abnormal side displays anterior disc displacement.

Reprinted with permission from MacDonald-Jankowski DS, Li TK, Matthew I. Magnetic resonance imaging for oral and maxillofacial Surgeons. Part 2: Clinical applications. Asian Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 2006;18:236–247.

The size of the condylar heads can be assessed first by ensuring that the patient has been properly positioned within the panoramic radiographic unit prior to exposure. This may be readily assessed by comparing the width of the vertical rami and the molar teeth of both sides. Any difference should then be compared to the patient. If the patient displays no difference, the image has been distorted due to incorrect positioning.

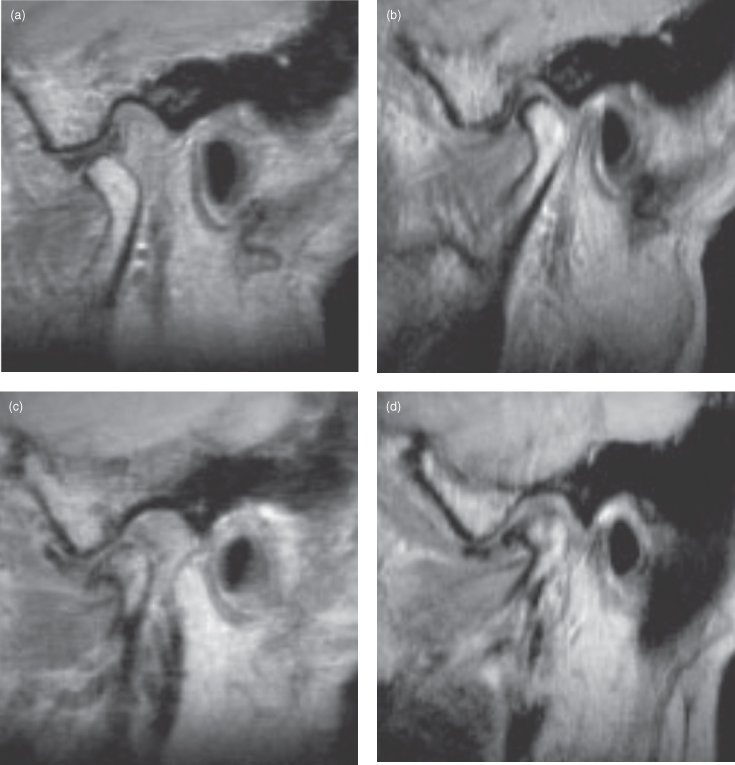

After it has been determined that one side is indeed larger, the clinician needs to determine which side is abnormal, because the other, smaller side could be hypoplastic. This can be appreciated by an abnormally shaped vertical ramus and an obtuse gonial angle (the angle formed by the lower border of the mandible and the posterior margin of the vertical ramus) (see Figure 10.30). Hypoplasia of one side can result from a developmental accident such as hemorrhage of the stapedial artery in utero with disruption of adjacent tissues including the condylar growth center. It can also occur in infancy due to radiotherapy. The midline of the mandible is skewed toward the hypoplastic side (Figure 12.5b). An increase in size could be due to hyperplasia, neoplasia, or dysplasia.

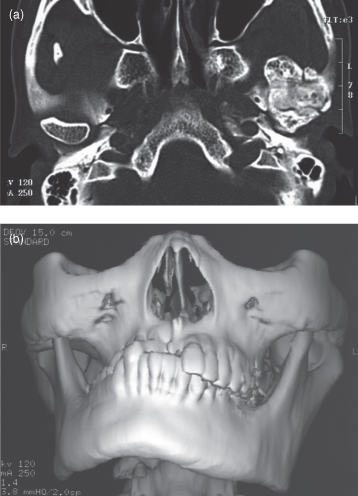

Figure 12.5. The computed tomography of an osteoma affecting the condylar head. (a) An axial computed tomograph (bone window) displaying the osteoma. In comparison with the normal ovoid-shaped contralateral condylar head, the affected condyle has substantially expanded in all directions. It has substantially reduced the joint space. (b) A three-dimensional reconstruction of the osteoma displaying it as an expansion mainly of the medial pole of the condylar head. There is a midline shift to the unaffected side and marked facial asymmetry.

Lesions affecting the condyle may arise either primarily within it, such as the osteoma (Figure 12.5) and chondrosarcoma, or arise elsewhere in the mandible and subsequently involve it, such as osteogenic sarcoma (Figure 12.6) and fibrous dysplasia (FD) (Figure 12.7).

Figure 12.6. Axial computed tomograph (bone window) of osteosarcoma affecting the condylar head. The primary site in the body of the mandible recurred twice after wide resections (See Figure 10.12). It has now spread to the condyle. The axial section displays />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses